On the corner of Main and Railroad Street in Whitesburg, Kentucky, stands Roundabout Records. This may seem like a roundabout way to begin an art studio visit; however, in this case, it makes perfect sense. The artist Lacy Hale and her husband Benjamin Spangler are the owners of Roundabout Records, just a stone’s throw away from Appalshop, where both she and her husband have been involved for years.

Lacy and I pretend-hug in this new world of COVID. I follow her back to her studio space, passing by records, speakers and a few guitars along the way. As we continue through the store, the art form changes from music to wood cuts and screens, as Lacy and her art take center stage.

“I always knew I wanted to be an artist. Both of my parents were creative – my dad played guitar (really, anything that had strings) and my mom, who is still living, loves arts and crafts. We grew up extremely poor and she was always making things. I remember one year for Easter she made us all (my three siblings and me) terry cloth bunny dolls. After my dad passed away in 2008 she made us art quilts out of his clothing.

I like to try my hand at a little bit of everything, just because it’s hard to make it as an artist here. You have to be an entrepreneur.â€

You can see that Lacy is indeed an entrepreneur. There are stacks of cards, T-shirts, and linoleum and wood cuts throughout. This might be a small space, but it is full of big ideas. A beautiful new print of Frida Kahlo is tacked to the wall. Lacy tells me it was recently included in an exhibit in New York where she once attended the prestigious Pratt Institute School of Art.

What was it like to transition from Eastern Kentucky to Manhattan and one of the world’s leading private art institutes?

“Pratt was an opportunity that I never thought that I would have. I only made it there because my community in Knott County rallied around me and helped raise money to send me there. My parents worked so hard to pay for it but it was just too much and I came home after my second year.

The culture shock wasn’t that intense – or at least I played it off like it wasn’t. I had obviously seen movies and shows with NYC in them. There were new things to learn, but the first time I stepped foot into the Met, I bawled my eyes out. Stendhal Syndrome is real.

I loved the subway! I had never been able to go anywhere I wanted for $1.50 or whatever it was at the time. In rural Eastern Kentucky, you must have a car. My family could only really afford the one my dad used to drive to work, so the subway was a whole new and exciting experience. Also, though, as soon as I opened my mouth people would assume I was stupid because of my accent. I dealt a lot with that.â€

Yet, she embraces her mountain accent with humor, pulling out a new screen recently completed.

“This is a design my husband and I came up with. It’s Dracula, but around here people would call him “Draculer.” He is wearing a Beechnut Tobacco hat and he’s got an RC Cola in his hand. I just did the screen yesterday. Not all of my work has a sense of humor, but some of it does. I think art should be enjoyed and it can be beautiful and funny and meaningful and blah, blah, blah.â€

I ask Lacy about #nohateinmyholler, her phrase and hashtag with a voice of its own.

“I don’t know if I’ve told you how that came about. The neo-Nazis were going to march in Pikeville in 2017 to try and recruit. What better way to try and protest then to make a piece of art that could be put on a sign or a shirt? People saw it and just really took to it. I’ve seen it all over this county and all over the world. I just sent one each to Japan and Germany. Holler transplants, I guess.â€

I ask: Do you feel you have always been a socially conscious artist?

“I’ve always been socially conscious. My parents instilled in me that all people are equal, and to stand up if you see an injustice. I did some work through the years with groups concerning social justice ideals, but when I knew that white supremacists were coming to a town an hour from me, under the guise of helping poor families in eastern Kentucky, I was infuriated. And so were some of the kids where I was working. At the time I was working with the Appalshop Media Institute, their youth media program. One of the youths asked if we could have an ‘Art in Response’ day to make protest signs and things. We thought it was an incredible idea! I had taught many of them to do block printing and we took a day and made posters and things.

The phrase ‘No Hate in My Holler’ came to me the night before and I carved it that day surrounded by a lot of local kids and adults who were also making protest pieces. It was so encouraging then and the response to ‘No Hate in My Holler’ has been incredibly encouraging ever since.â€

Lacy pulls out the screen for #nohateinmyholler. This is actually her second screen. The first one wore out after she printed over 500 t-shirts in June and July.

After George Floyd’s murder and the breaking news of the police shooting of Breonna Taylor, she felt a need to take action. She made a post saying she was going to donate 75 percent of all funds raised selling the t-shirts to Black Visions Collective and the Louisville Bail Fund. The orders came pouring in. She has raised over $5,000 for these important causes.

Lacy demonstrates how to make a split fountain, a process of screen printing and printmaking, placing more than one ink color on the same screen to achieve an ombré or rainbow effect. The paint blends on the screen as you use a squeegee to push the ink through the screen onto the medium. It’s a method used to place multiple colors on a print without using a different screen for each color. The paint colors line up on one side as Lacy begins to pull them through. The colors repeat and pull through again as the paint finds its path – not unlike Lacy finding her path back here and home.

It seems as though Lacy’s work is everywhere in Whitesburg. We leave the record store and walk over to the Boone Motor Building also known as AMI (Appalshop Media Institute), where she has created some of her murals. Her next mural was supposed to be a community collaboration, but in this new COVID age it will now be a solo piece.

We took a drive up to Jenkins, where she tells me about her mural there, commissioned by Appalshop.

“The community wanted to move away from coal. They didn’t want it to be about coal. It could respect the history, but they wanted to move forward.â€

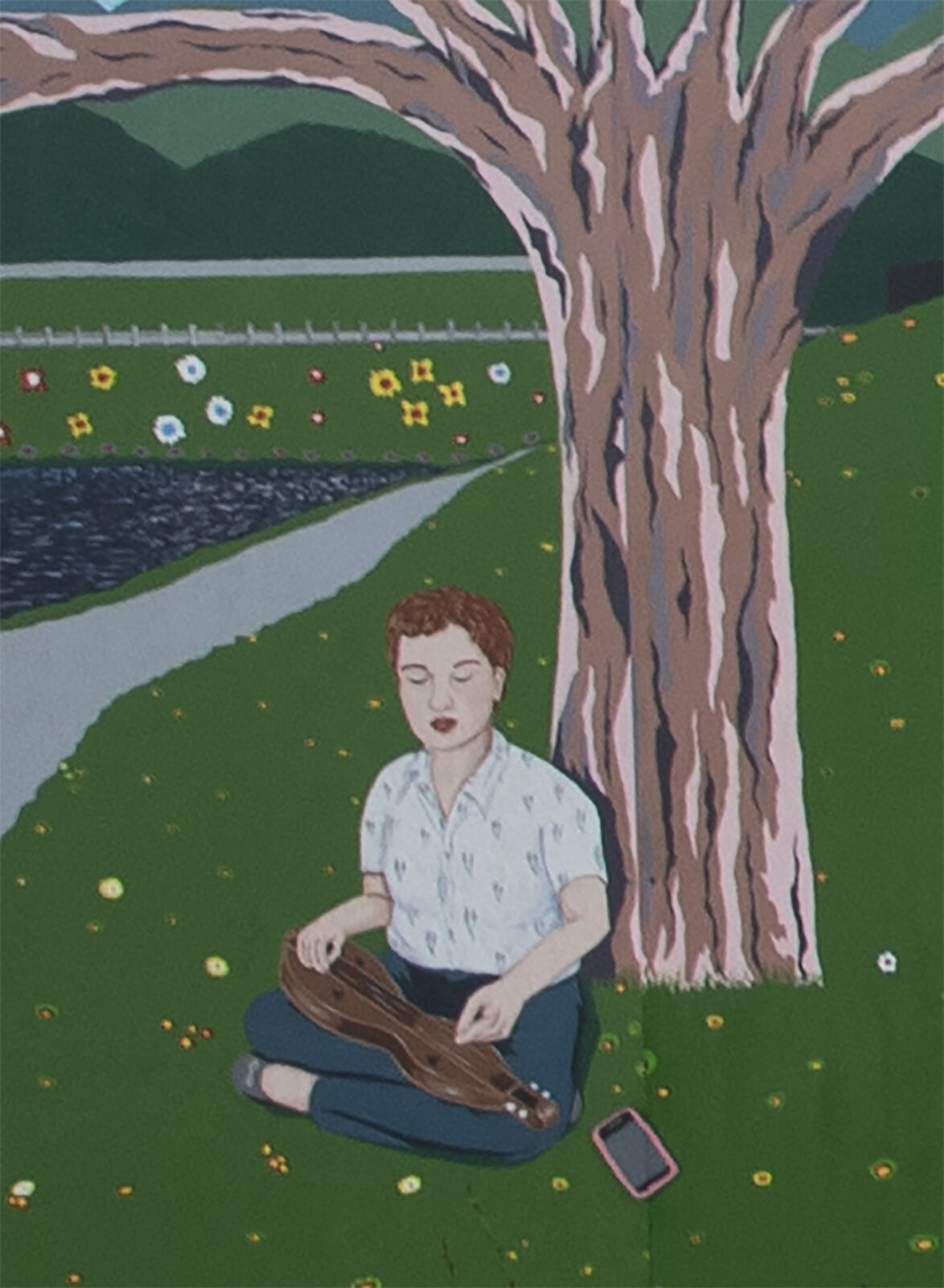

The mural shows a miner’s head lamp pointing its way to the future, leaving the black and white world of coal behind and peering into a new, colorful age. I particularly love the young girl with a dulcimer and an iPhone on the ground next to her.

“I designed it like a paint-by-number and the community painted it. The age range was 7-87 years old and there were 60 community members.

I view a lot of public art as community outreach. Working outside as people walk by gives an artist the chance to answer questions and talk to folks that may never set foot in a museum. For most of my murals, I have worked with organizations and we always get the community to give us feedback, as well. Sometimes they’re involved in the design process. It’s important for the community to have some buy-in instead of forcing a piece of artwork on them.â€

Her Possum and Pokeweed mural brought about a lot of discussion. Lacy appreciated the possum for its resilience, but she learned that others were not so affectionate toward them. In the end, the piece was embraced by the community and can be seen in Harlan.

How does place influence your work?

“I am the 5th or 6th generation of Hales to be raised on the property where I grew up. I grew up running wild through the mountains and the creeks, working the garden with my dad, wandering the family cemetery looking at my ancestors’ headstones. I think eastern Kentucky gets into your bones and blood. The mountains will always feel like home, no matter where else you may live. I think I really settled into my artistic voice when I began doing pieces about the place I love. I’ll always be searching for and refining that voice but it feels right and I feel good about the work I produce. My identity is so entwined with this place. Making the decision to move back here, live here, make a way here, and make my work here was a very conscious one.â€

Did you ever feel bad having to leave Pratt?

“At the time I had to go, it felt like it was time to go. I was a holler girl in New York City which was awesome – I learned a lot and I met a lot of really cool people, ate a lot of different food I probably wouldn’t have had otherwise, but it also made me realize how much I missed this place. I was lucky to be there for the time I was, but I was ready to come home.â€

I think home is glad to have her back.