On May 25, 2020, Derek Chauvin, a white Minneapolis police officer in his mid-40s, evidently decided that 46-year-old George Floyd’s alleged infraction of passing a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill should cost him his life. Three other officers watched as Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds – even longer than we had originally understood.

Despite exhortations from the other officers and the citizens standing nearby, despite Floyd’s pleas to let him breathe and his invocation of his recently deceased mother, Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck until he was no longer breathing. And then he kept his knee on his neck for another three and a half minutes.

Chauvin’s defense attorneys have posed a number of counterarguments during the initial days of the trial, including that Floyd had illicit drugs in his system, that he had a heart condition that contributed to his death, and that his physical size made him a threat to the officers even after he was handcuffed and lying face down on the ground.

Over the past 10 months, we have learned a bit more about George Floyd and his family. We know he was a college athlete who struggled to stay in school and struggled with addiction. He spent some time in prison. We know he had moved from Houston to Minneapolis to try to turn his life around. During the trial, we saw his fiancée describe his kindness when he had first approached her at the Salvation Army where he was working security. For months we have witnessed the courage and the oratory and the passion of Floyd’s siblings and his cousins. We’ve seen the confusion of his bright-eyed young daughter whose father is now famous.

He has come to feel like someone we knew, like someone we might encounter joking around at a corner market just like Cup Foods.

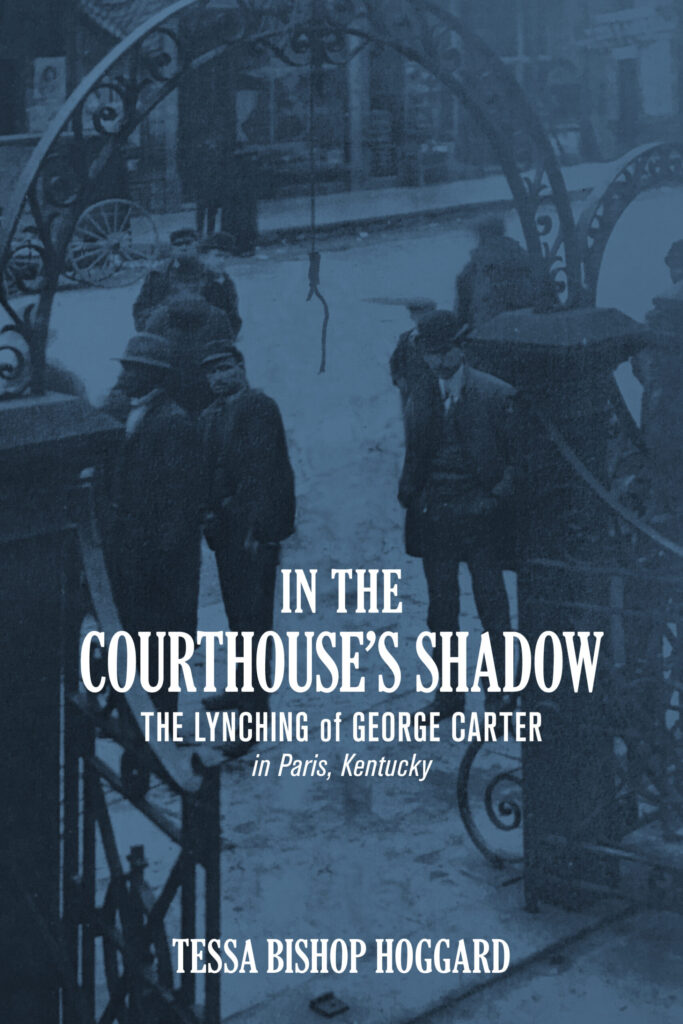

That’s what Tessa Bishop Hoggard has accomplished in her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow. Through diligent research, she has fleshed out the story of one heretofore anonymous young Black man who was lynched in Paris, Kentucky, in 1901 after being accused of a minor crime. Like George Floyd, George Carter had previously run afoul of the law but was trying to settle down with his young family and build a good life. Like Floyd, Carter never had a chance to claim his innocence or plead his case. A group of white men with power in his community decided that he should pay with his life for a crime that we have no evidence ever occurred.

We also learn that others who endured a fate similar to Carter’s were described in the press the same way, whether accurate or not: “burly negroes over 200 pounds.†As in Floyd’s case, physical size – or perceived physical size – justified illegal actions.

In Hoggard’s book, we learn about Carter’s family, their hopes and their dreams, and what happened to them after he was killed. We learn the fate of his two young daughters. We also learn about the family of the white woman who identified him as the man who had assaulted her, a crime that was originally reported as an attempted purse snatching. We learn about the fate of her eight-year-old son, who witnessed the assault and helped the sheriff identify Carter as the assailant.

We learn that George Carter, like George Floyd, was a father, a son, a brother – a human being. He was not just a statistic of early 20th-century racial injustice. Just as George Floyd was not merely another victim of 21st-century police brutality.

This is a problem our nation obviously has not solved. On March 18, during a House Judiciary Committee hearing on anti-Asian American violence and discrimination, Republican Congressman Chip Roy of Texas said, “We believe in justice. There are old sayings in Texas about find all the rope in Texas and get a tall oak tree. We take justice very seriously. And we ought to do that. Round up the bad guys. That’s what we believe.” Afterward, Roy refused to apologize for his choice of words and doubled down on the language.

As columnist Charles Blow recently wrote in the New York Times: “It is hard not to draw the through-line from a noose on the neck to a knee on the neck. And it is also hard not to recall that few people were ever punished for lynchings. Motionless Black bodies have been the tableau upon which the American story has unfolded….â€

Those who witnessed George Floyd’s murder have testified about their sense of helplessness at the time and the enormous guilt they still carry. Some videotaped the crime and shared it with the world in horror. Those who discovered George Carter’s body hanging in front of the courthouse on that cold February morning tarried at the scene and took photos, seemingly proud of the town’s latest trophy and the message it sent.

Is that a sign of some progress in the last 120 years? Are we finally beginning to push back on these unforgivable acts of oppression and subjugation? What would we do if we found ourselves witnesses to such a crime? Would we simply stand by and watch, as the two doormen in New York recently chose to do as a 65-year-old Asian American woman was being assaulted on the sidewalk in front of their building? Or would we find the power to act?

In 1901, George Carter was only 21 years old when he was lynched. I wonder if he, in his final moments, silently called for his mother.

Sallie Showalter’s blog Murky Press is proud to offer In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter in Paris, Kentucky through Amazon or by contacting Murky Press directly.