On March 13, 2020, Breonna Taylor lost her life at the hands of police. An act that the community feels is senseless and yet another example of out-of-control policing and racism in the United States. In an effort to help the community make sense of the tragedy and to heal, the Speed Museum decided to host a show dedicated to the memory of Taylor.

Museum Director Stephen Reily told me when I covered the initial announcement of the show for LEO Weekly, “It’s been a year in which everything going on in Louisville has challenged us to think about how an art museum serves its community at times like this.â€

“As the year went on, we really thought about what an institution, and communities that are going through trauma, are supposed to do. How do we each find our way to help? Our way is art.â€

Art is a powerful healer and there are many parts of the Taylor show that work well in that respect.

Under the curation of Allison Glenn, associate curator at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, the show transformed from idea into a collaborative heavy lift in which Glenn was tasked with satisfying the role of a curator in a historic institution, lifting up a grieving family and community, and challenging visitors who don’t understand or expect an art museum to be a place of provocation.

Museums of the past were certainly repositories of wealthy folks’ treasures and, to some degree, this remains true; the bulk of museum properties are made at the bequest of wealthy donors. The modern museum has to respond in different ways. It has to grow its audience in an increasingly diverse economy and populace. That means museums must be flexible and willing to take on the task of tough topics that can address issues in art and community previously ignored.

Rightfully, this is a gamble the Speed Museum needed to take and one that I think has important benefits for the audience and the community. One of which is putting a spotlight on issues that have happened in the areas surrounding the Speed for many years.

Walking into “Promise, Witness, Remembrance” I am immediately struck – not by the portrait of Taylor that anchors the show in the distant hall – that this is a show about the life of a Black woman in the oldest halls of one of the (perceived) whitest institutions in the city. In the doorway of the first room, “Witness†is flanked by two long blue flags covered in white stars. These works, an ongoing project by Hank Willis Thomas, use each star to commemorate a person killed by gun violence in the United States. The two flags created in 2019 and 2020 are the artist’s way of honoring the dead, including Breonna Taylor and other locals lost to gun violence like David McAtee and activist Travis Nagdy. As the flags hang dark against the luminous white room, it is an immediate contrast to what the Speed has been and how this show represents a move towards what I’d call a better future for the institution where confrontation becomes part of the experience. Art can confront and, from that, transformation can happen.

In the same room, Nari Ward’s work, “We the People,†raises the question of what a common “We†implies. These words from the preamble of the Constitution of the United States, formed from shoelaces – a simple thing that keeps our shoes tied – highlight the fragmentation of this nation as it continues to struggle with the implications of our common history.

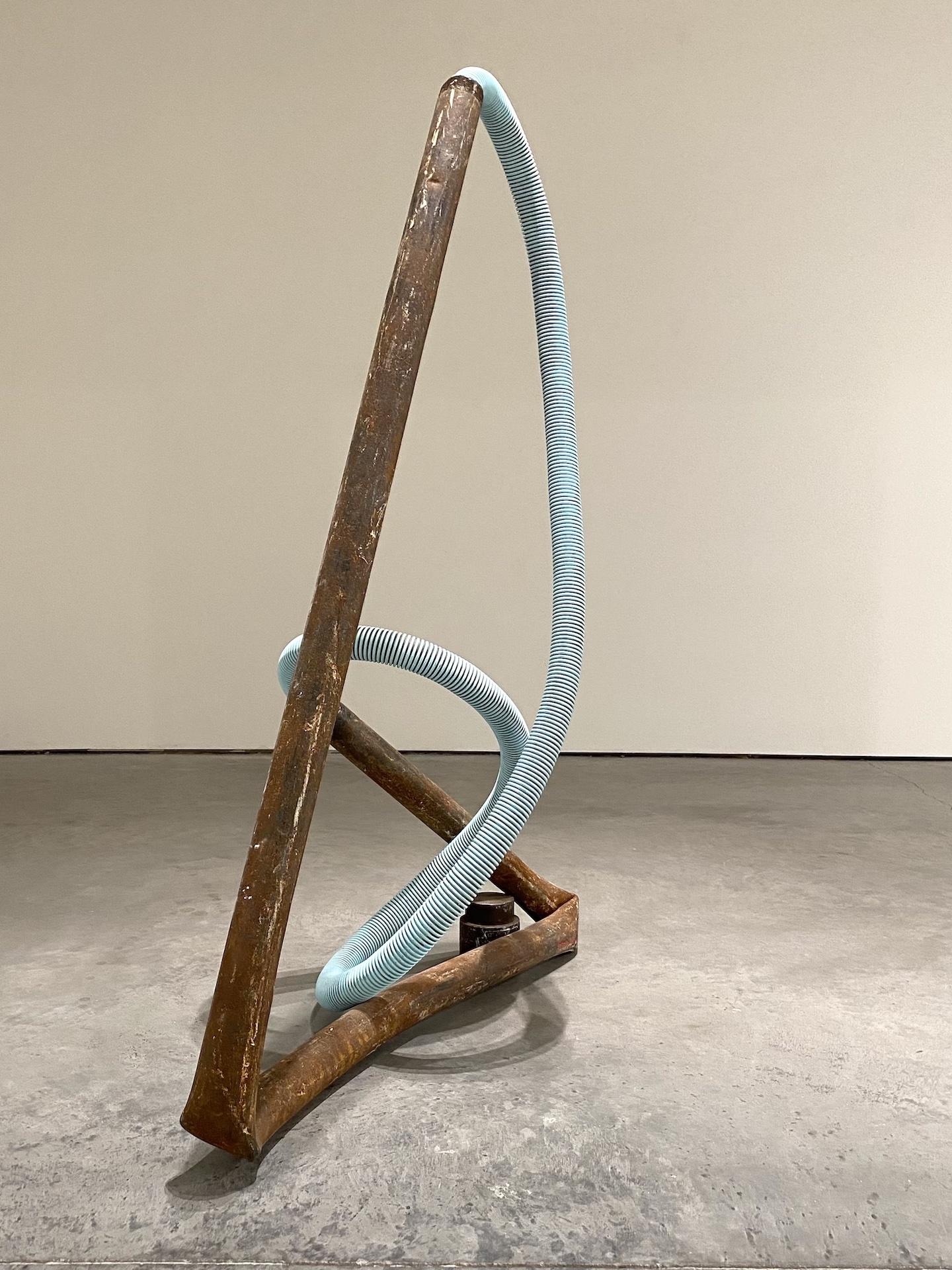

The strongest rooms of the show, in my opinion, were the next two. The first of the two included works by Lorna Simpson, Alisha Wormsley, Louisville native Sam Gilliam, Theaster Gates, and local photographer T.A. Yero. The Theaster Gates piece, “Alls my life I has to fight†(named after a line in the movie The Color Purple), shows two black figures, presumably a mother and a child. The statue is set upon a patchwork carpet on a stone block and housed inside a rusting cage. It is powerful in that it gives voice to the repeated notion of being trapped in a place where we should be honored for our contribution. Instead, we are given fancier bird cages but never true freedom.

The Alicia Wormsley piece, “There are Black People in the Future,†borders the entire top of this room. It is a reminder that Black people are a part of not only the history of this nation but that our existence will persist into the future – essentially this is a guarantee and a confrontational one. It challenges the notion that white supremacy might somehow extinguish the contributions, culture, and perhaps the existence of Black people in America. The truth is, as Wormsley says, “There are Black People in the Future.â€

In this same room, the collection of photography from local photographers Erik Branch, Tyler Gerth, Xavier Burrell, and T.A. Yero offers an intimate portrait of the protests that followed the shooting of Breonna Taylor. The summer of 2020 was a time filled with people in the streets, peacefully protesting the violence that took Taylor’s life. These photographs show the passion and the weariness of those who held vigil last year in honor of Taylor’s life.

Of these, the T.A. Yero photo “Healingâ€, taken a month into the protests and showing two women embracing, the pain and exhaustion present on their faces, is especially poignant because it speaks past the events of last summer, again, into the weariness of being Black in America.

The pain is larger than this one event and this event is larger than Louisville or these two women. This photo says this perfectly. It puts an important human face on the display of these artworks. It prepares the viewer for what is to come.

In the next room, a video installation by Jon-Sesrie Goff entitled “A Site of Reckoning: Battlefield†(2016) shows the audience almost five minutes of video of The Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, the site of the racially motivated murder of nine Black people in their place of worship. One of the people killed, Reverend Clementa Pickney, was a personal friend of the artist and his family, so this piece takes on a personal tone. The footage of memorials and worshippers returning to their church, symbolic of the endurance of Black faith and the grit to persevere, plays as the soundtrack rings throughout the entire show: a poem read by Sonia Sanchez with a capella group Sweet Honey in the Rock singing “Stay on the Battlefield.†It is a moment of respite, a chance to remember, to feel the anger, hurt, and sadness that comes with the American Black experience. It is where my first tears flowed.

As a Black woman, this piece spoke to my experience in America. It felt like a conversation – one about what we know about life as Black people here and what we share with each other in that life. We know each other even when we don’t know each other, and seeing our triumph in the midst of tragedy, while hearing “Stay on the Battlefield,†was a reminder that this iteration of America may be hard but it is our staying power that sings out in the end. It is a beacon to a protracted revolution.

In the next room, “Remembrance,†the Amy Sherald portrait of Taylor hangs in the center of the wall opposite the doorway. The blue of her dress glowing and the pose projecting a strength and ease that fits the description many who actually knew Taylor had of her. Sherald captured, as she often does, without gimmicks, the power of Black womanhood. In the portrait, the dress shows a hint of leg, a hand on a hip, and an expression that seems to challenge the viewer – a dare, if you will. It puts Taylor beyond the descriptions of her as simply a young woman wrongly murdered. She was that. It moves Taylor beyond being an EMT, as she is so often described. She was that, too. Most of all it says to the viewer that Taylor had presence and value and that she mattered. It dares you to take that away.

This would seem to be a perfect place to end the show but tucked away in the front of the museum’s cinema was one more piece, “BLKNWS,†by artist Khalil Joseph. It is a re-imagining of the Black experience in media through the lens of a Black person. The piece offers humor and joy, and apparently is an ongoing work that will continue to evolve as it challenges news media to do the same. It is unfortunate that it was tucked away in the lower level. I almost missed it. It was one of the pieces I most wanted to see.

Overall, “Promise, Witness, Remembrance” achieves its goals. I don’t know the time frame of the project but I still felt something was missing and whatever that was, had something to do with time. I think I wanted more work, maybe some of the work by local visual artists who were not photographers. Perhaps the memorial that was created in “Injustice†Square could have had space dedicated for a viewing, more than just the lone piece by Aron Conaway, which was sequestered away in a corner near the cafe. I haven’t quite put my finger on it but I know that I wanted more time and more to see.

Still, without a doubt, the show has many successes. It brings together important elements of Black experience, questions the American experience, and challenges us to look at our nation, our lives, and our challenges with different eyes. And, it does effectively honor the life of Breonna Taylor and cements her place as a torch for justice.

Top image photo credit: Xavier Burrell

“Promise, Witness, Remembrance” runs at the Speed Museum in Louisville through June 6.