The protests that erupted after the police killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, and gained momentum with the murders of Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, fixed a particular set of images attached to the word “resistance†in American minds: masked demonstrators filling city streets, storefronts smashed and looted, confrontations between civilians and police. These scenes were all too familiar in St. Louis, where the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in 2014 had galvanized the beginnings of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Stories of Resistance,†an extensive group show on view at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (CAM) through August 15, 2021, expands this visual conception to encompass myriad forms of resistance across different cultures. The exhibition includes more than three dozen works by 19 artists, as well as Radio Resistance, a broadcast program (also available as a podcast) that pairs artists with activists and agents of change in conversations about collective action and dissent.

Organized around themes of language, existence, and movement, “Stories of Resistance†opens quietly, with ex libris, an installation by Emily Jacir originally commissioned by dOCUMENTA (13). A small, light-filled room houses dozens of photographs of pages from books taken from Palestinian homes, libraries, and institutions by Israeli authorities in 1948. They are displayed on narrow rows of shelving across all four walls to form their own library of sorts. Six thousand of the nearly 30,000 books stolen remain in the Jewish National and University Library; it was here that Jacir began photographing their contents, captivated by the traces of human presence found in coffee stains, marginalia, notations, and inscriptions. Mark-making becomes a visual assertion of the original owners’ presence, and a means by which the Israeli institution is denied rightful ownership of the objects.

In Banu Cennetoğlu’s work Gurbet’s Diary (27.07.1995-08.10-1997), it is the presence of the author that is amplified. Gurbetelli Ersöz was a Kurdish journalist tortured and imprisoned by Turkish authorities before joining the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in 1995; she was killed in 1997 in Southern Kurdistan and her body never recovered. Her diary of her time with the PKK was published and promptly banned in Turkey. Cennetoğlu replicates the entirety of Ersöz’s diary on 145 lithographic limestone tablets, simultaneously giving her words both portability and permanence: printed on paper as lithographs, the text can be widely disseminated, yet the weight and size of the tablets themselves prevent easy transport (or smuggling, as political persecution so often dictates). The soft limestone eventually wears down, and tablets can be reused to create new lithographs; indeed, Cennetoğlu is reusing tablets that once held other text or images, leaving the lingering question of what other narratives have now been lost to history.

Bani Abidi attempts to prevent that disappearance with an ongoing series of portraits of journalists, political activists, and other dissenters persecuted by the Pakistani state (and thus in danger of being abducted and killed by political authorities). Three such individuals are portrayed in the twelve small watercolors that comprise The Man Who Talked Until He Disappeared, each individual fading in color and detail across a progression of four paintings. Depicting their potential vanishing becomes an effort to safeguard against it, an artful signifier to the state that if these men suddenly go missing, we will know who is responsible.

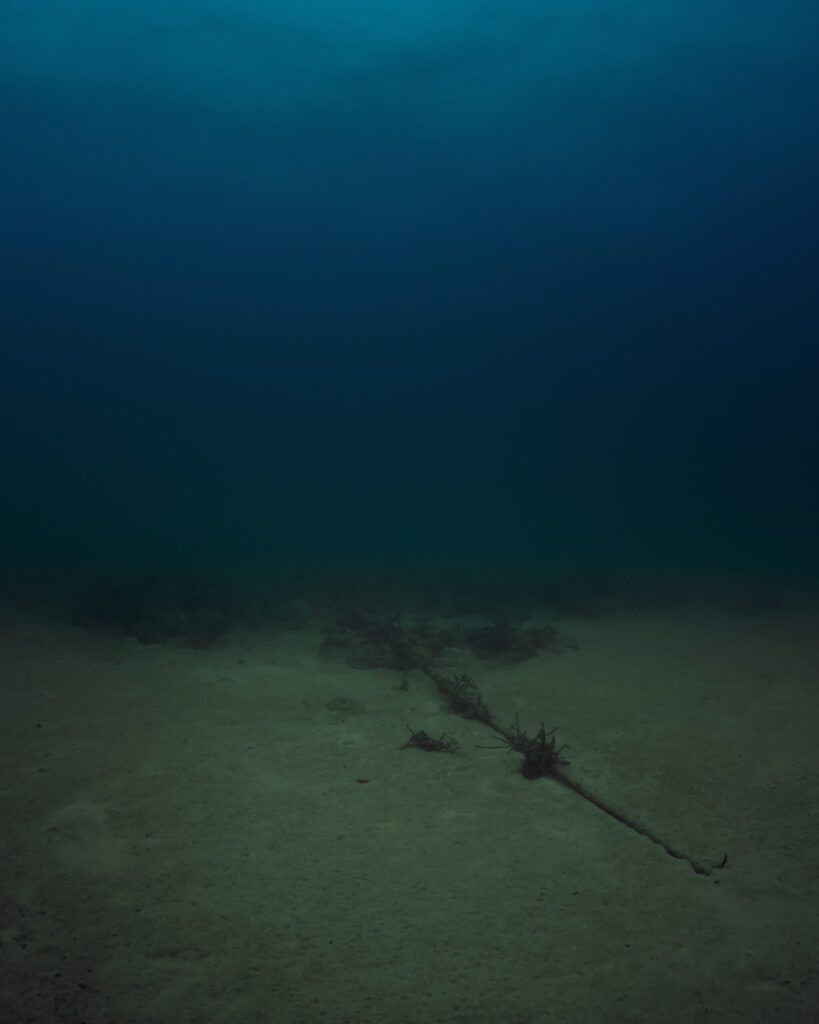

Documentation as a form of resistance drives other works in the exhibit as well. In Trevor Paglen’s two large C-prints, Columbia-Florida Subsea Fiber (CFX-1) NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable, Caribbean Sea and Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1), NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable, Atlantic Ocean, sublime gradients of deep green and blue ocean water partially obscure the massive cable systems that transmit telecommunications data, those personal conversations that are often covertly monitored by corporations or the government; the hidden environmental costs of digital technologies is implicit.

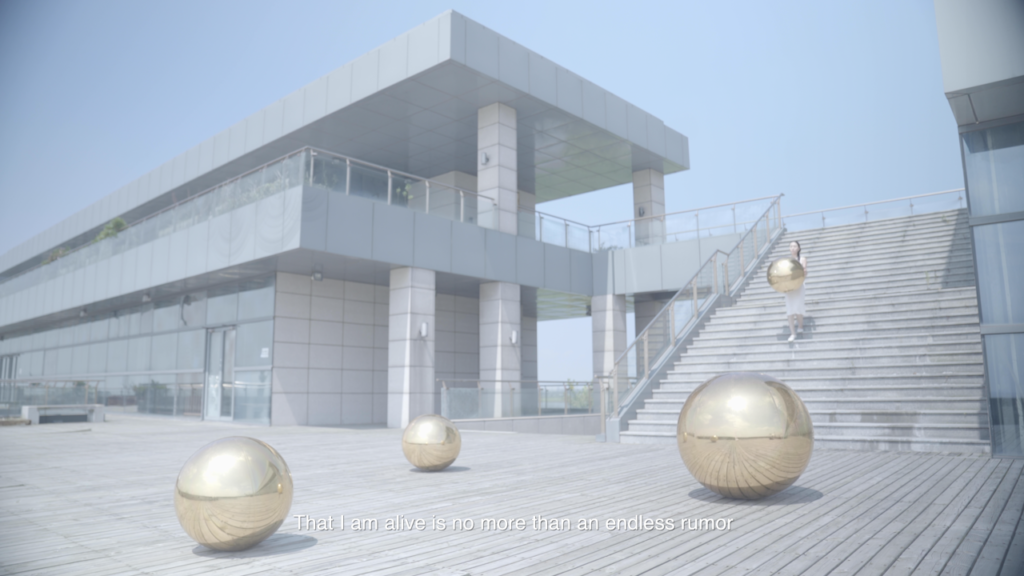

Jen Liu’s weird and wonderful Pink Slime Caesar Shift: Gold Loop highlights the toxic repercussions of gold extraction from discarded electronic equipment in a 28-minute 4K video that is equal parts surrealist dream sequence, corporate instructional tape, and dystopian film noir. In the seemingly altruistic act of recycling obsolete smartphones and computers, consumers initiate a process – unseen by them – that subjects female extraction workers in South China to poisonous chemicals that then seep into the local waterways; the labor activists who protest this harmful practice often mysteriously disappear.

While gold orbs feature prominently in Liu’s video, Candice Line uses the materials of colonial economies – namely sugar, opium, and tobacco – in her laboratory-like installation On Being Human. She creates a complex distillation system that culminates in a wooden structure resembling a water torture device that slowly drips onto and erodes a mass of unfired porcelain equal to the weight of the artist. This juxtaposition of the human body with the instruments of capitalist oppression is echoed in Slave Rebellion Reenactment performance still 1, taken during artist Dread Scott’s 2019 work in which hundreds of Black and Indigenous community members dressed in period clothing reenacted the 1811 rebellion that took place just outside New Orleans. Captured as the reenactors marched past sprawling industrial plants billowing white smoke, the photograph seems to foreshadow the source of future human and environmental degradation.

The earth has returned to a pre-industrial state in Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s 20-minute single-channel video The Boat People, which follows a group of five young children as they arrive by boat on an island filled with relics of past civilizations, both ancient and recent. In an effort to collect and understand the stories of these cultures, the children create wood carvings that replicate the artifacts and then burn the carvings, they explain, “to release them.†Objects hold meaning, whether they are the diaries and clothes and personal items that tell our individual stories or the paintings and sculptures and films we see in museums that communicate a broader collective narrative. In making these items visible, curators uphold one of their earliest functions as caretakers not just of objects, but of the stories they hold.

After a year in which arts institutions have come under increasing pressure to correct their colonial legacies and adopt more egalitarian frameworks, “Stories of Resistance†demonstrates that not only can museums effectively respond to current cultural conversations, but actually drive them. Buttressed by a robust program of community-engaged events, including book discussion groups, film screenings, and panel discussions, the exhibit stands as powerful evidence that the museum can become a locus for critical discourse and social critique – the site of our ever-evolving human narrative.

“Stories of Resistance†can be seen at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (CAM) through August 15, 2021.