“I too think that great art will come out

of the Middle West…It will come from

the artists who perceive their environment,

not just in isolation, but in relation to the whole.â€

– Stuart Davis, Art Digest, 1935

In the 1930s Regionalism became a prominent style of painting in the Midwest. In the aftermath of the Great Depression, Regionalism was a balm, a glorified vision of white, rural, Christian America. Though not its expressed intent, Regionalism got uncomfortably entangled with nationalism. The style faded by WWII, but its nostalgic and mythologizing platitudes shaped how America saw the Midwest and how the Midwest saw itself: the Heartland, the Breadbasket. Fly-over country. Placid lakes, big shoulders, and steel mills.

“The Regional,†currently on view at the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) in Cincinnati, seeks to “complicate the ways that we think about the Midwest and its relationship to land, home, belonging, nostalgia, trauma, healing and identity.†Amara Antilla and Jade Powers, the show’s curators, leapfrog over any staid notions of Regionalism. The show feels very much of the moment. Most of the artists featured are under thirty-five, and the works emphasize the process of reflecting on and repairing traditional narratives of the Midwest.

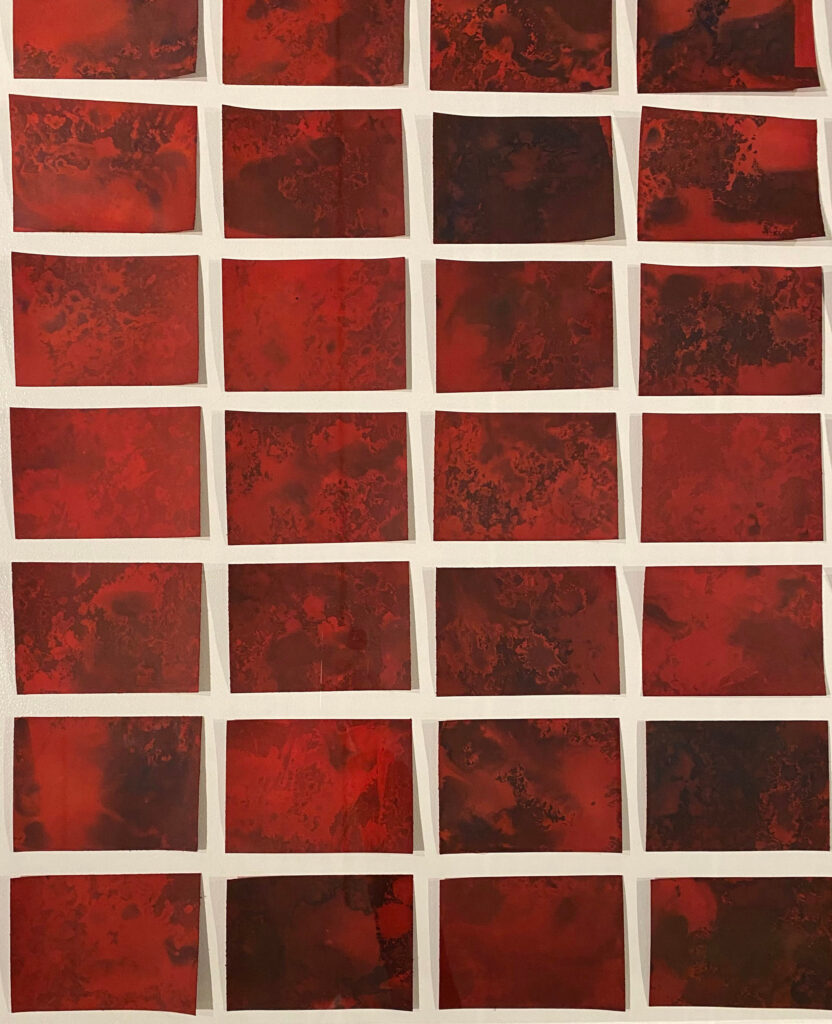

The fifth-floor gallery really captures this reparative mode, with works by Dakota Mace, Hellen Ascoli, and Margo Wolowiec. The materials these three artists use are intimately linked with land and lineage. Mace’s installation Dahodiyinii (Sacred Places) is composed of two-hundred card-sized cyanotypes, dyed deep red with cochineal and arranged in a ten-foot grid pattern. The variations on the prints resemble aerial land photography, and are remnants from being outside on the ground, exposed to wind, water, dirt, and sun. Dahodiyinii is accompanied by audio of Diné (Navajo) people talking about the “Long Walk,†a forced migration implemented by the US Army in 1864. The work takes a bold, archival approach to saving stories of land and peoples that history may want to forget.

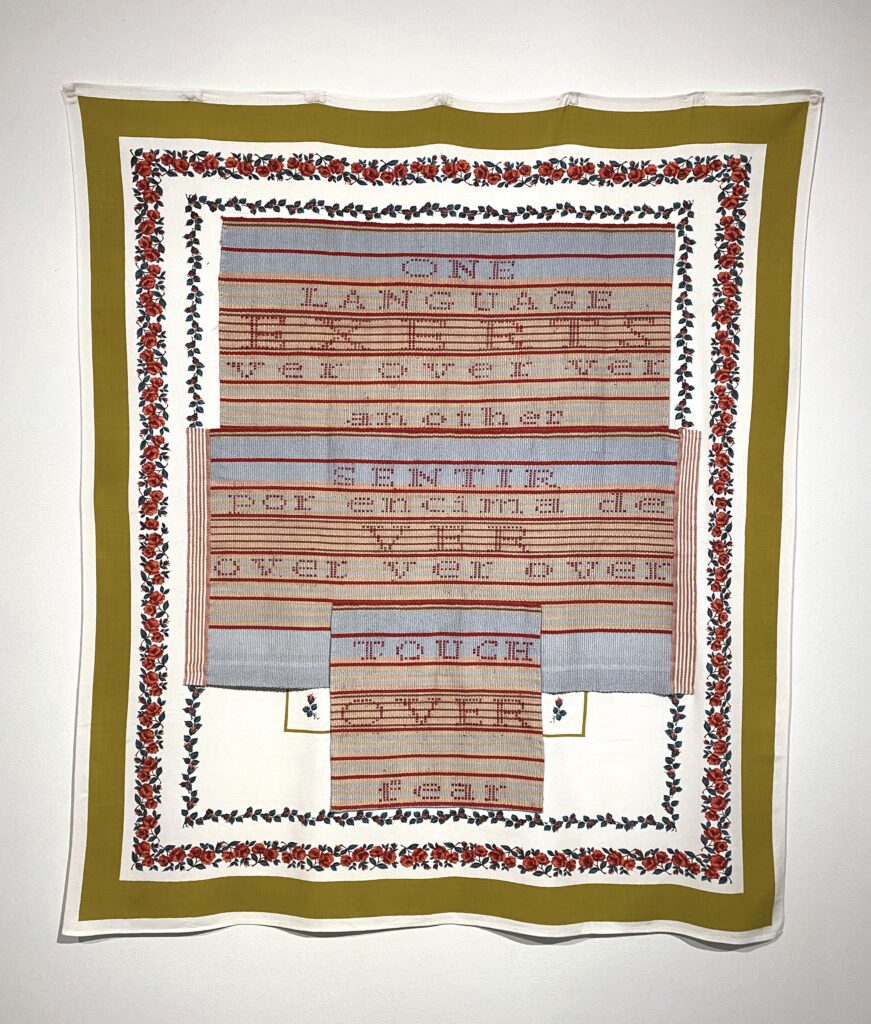

Ascoli’s fantastic woven textiles show the hybridity of language and culture and deal with issues of immigration – who do we keep out and why? What does it mean to be “native†to a region? Woloweic’s textiles are colder. They buzz with the feeling of TV static – a brief, empty moment between disasters. Her works are aggregates of information and anxiety relating to climate and social crises in her hometown of Detroit and beyond.

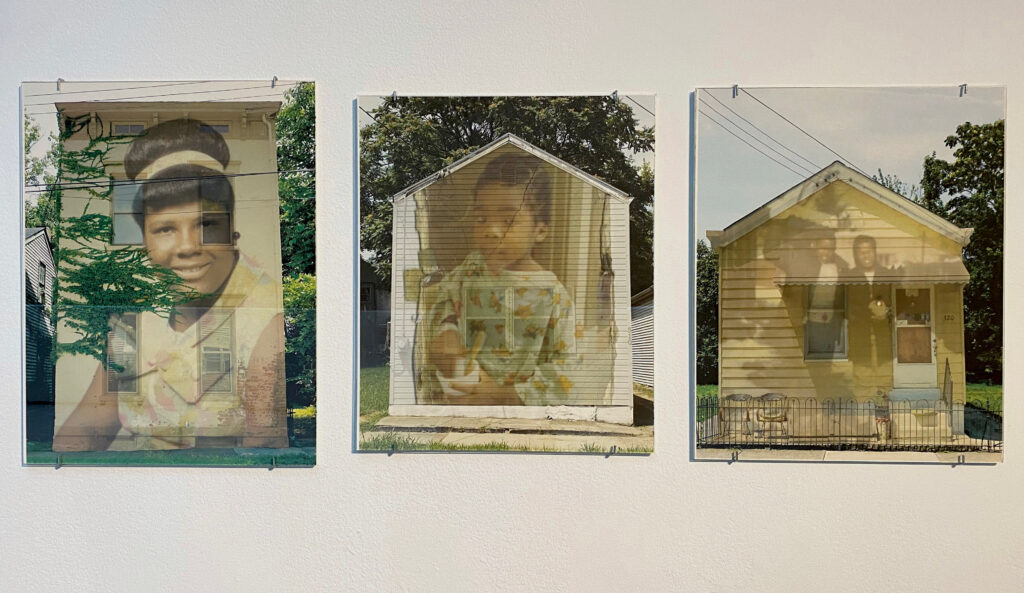

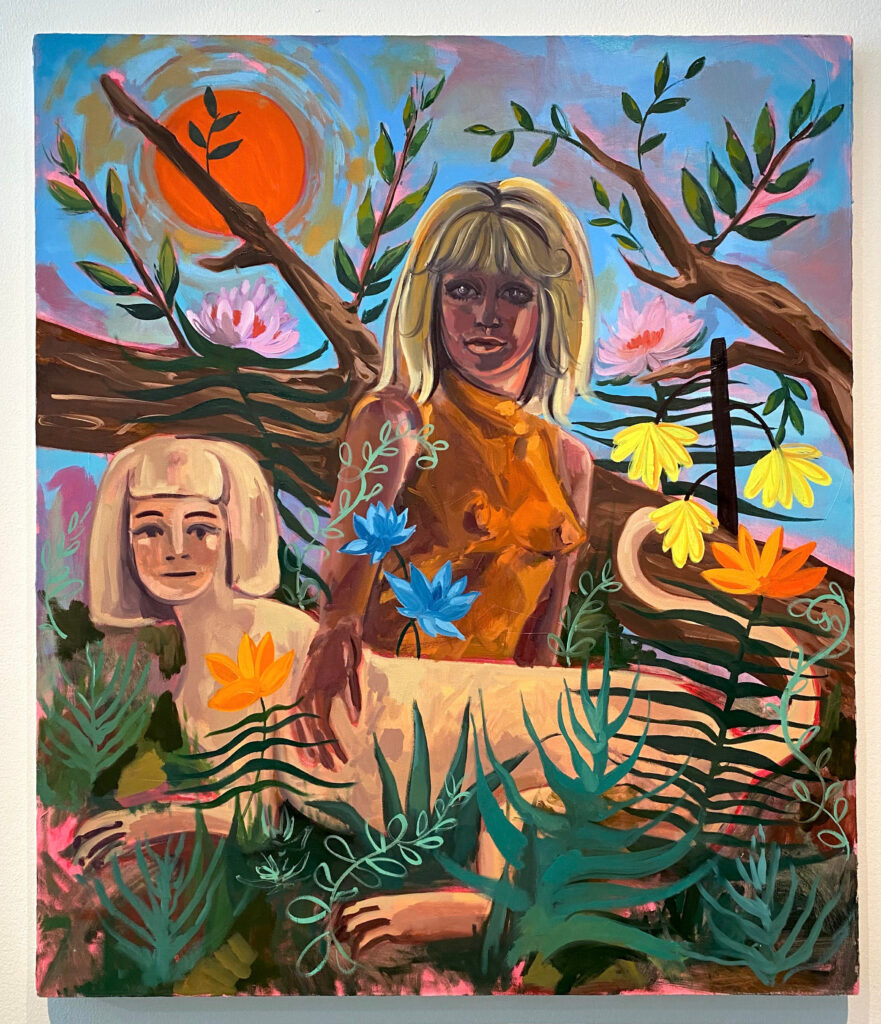

“The Regional†can be weighty – the show is wrestling with a lot of urgent conversations and catastrophes that stretch further than just the Midwest. But the show is also contemplative. There is a slowness and a generosity to this collection of works. Portraiture by Pao Houa Her, Anissa R. Lewis, and Gisela McDaniel create moments of communion and expand the notion of who inhabits the Midwest. Subject and landscape merge, and identity is built through a sense of place – where are you right now? And how does that shape who you are?

There’s also an intense interiority to the show, a modesty that is very much associated with the Midwest. Isa Gagarin’s wall installation in the lobby subtly abstracts landscape – a windy prairie, maybe, a lake – somewhere, quiet, reeded, receding. Alice Tippit’s four small works are meditations on the nature of painting. Seemingly simple, but emotionally stirring, they have a fantastical sense of being lit from within. Dan Gunn’s stoneware floor lamps, in the shape of frogs, smack of a weird inside joke. A rogue lawn ornament. His wooden sculptures Wetland Scenery and Bittersweet Scenery adopt a similar tone, turning the folksy Midwestern landscape in on itself, as though they were theatrical backdrops.

Lorena Molina’s Reconciliation Garden is perhaps the most striking work in the show and the most fully integrated with the curator’s goals: to see the Midwest, or any region for that matter, as inextricably connected with all others – not just materially but through a shared consciousness. Molina currently lives and teaches in Cincinnati but is from El Salvador. The room-sized installation features plants in colorful pots, bright grow lights, and a seating area where you can watch a video and participate in a guided meditation on coffee – the land it’s grown on, the people who grow it, how it gets to your cup and whether or not you consider all of these labors when you take a sip. There are also deeper political currents, as Molina considers the ethics of consumption and the United States’ self-motivated involvement in other nations’ conflicts. Molina also connects with the real world beyond the museum’s walls; through the work, you can donate directly to the Coffee Farmer Reconciliation Fund.

The CAC is working with an idiosyncratic space – aside from a few large galleries, there are a lot of tight corners and small corridors. Some of the works in “The Regional†could have benefitted from more space to breathe, like HÆ°Æ¡ng Ngô’s video work The Voice is an Archive, or the excellent works of Matthew Angelo Harrison. His use of materials, which reference both the African Diaspora and the industrial history of Detroit, is impeccable. It could be argued that “The Regional†would be more impactful with a central message. But imposing a clear path through, or more boundaries in an exhibition aiming to push against them, would be to miss the point.

What’s most to love about “The Regional†is that it is hopeful. It asks us to “reconsider what the Midwest is and might become.†It asserts that there is a future and that we are all in it, together. It asks us to think how we might build resiliency into our interconnected systems, which are particularly stressed right now. In many ways “a regional†mindset is a necessary construction – a way to understand yourself and others. But we also must be willing to dissolve these separatist delineations, especially when a moment demands that we consider how we are all tied to one another.

“The Regional†is on view at Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati until March 20, 2022. The exhibition will then be on view at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO, from June 2 through September 11, 2022. A digital catalog with essays and interviews can be found here. Top image: “The Regional†at the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati. Image courtesy of the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati. An installation view of various artworks with the words “The Regional” on the wall. In the foreground is an installation piece of fabric and wood that sprawls upward from the floor and goes onto the ceiling.

UnderMain: On the Road sends writers out of Kentucky to explore the visual arts in cities of the Midwest and near South. This program is generously supported by the Great Meadows Foundation.