On a cold Friday evening in February, a small group of people gathered at KMAC Museum in Louisville to hear glass artists Ché Rhodes, Corey Pemberton, and SaraBeth Post in conversation with curatorial director Joey Yates. Rhodes, the academic among the panelists (he serves as Head of Studio Glass at the University of Louisville’s Hite Institute), considered his craft’s tendency to the traditional and gave a gentle laugh. “The theme of every glass exhibition over the past 50 years, generally, has been glass.†What they had done at KMAC, however, was different. “I think you could go through this exhibition and leave not realizing you’ve seen a glass show,†he said.

You could also go through Crafting the Vernacular and not know that all six artists in the show are Black – a deliberate intention of the artists, when many curators and gallerists who show the works of Black artists are more inclined to shout this fact. (Yates, it should be noted, has a long history of showing Black artists – Simone Leigh, Paul Sepuya, Sanford Biggers, Ed Hamilton, William Duffy, and Elmer Lucille Allen quickly come to mind – and had been in discussion with Rhodes about an exhibit many months before racial protests erupted in Louisville.)

Instead, the collective works in the show seem to express racial identity as one of many identities: one artist may be a Black artist, but also a glass artist, a woman artist, a Millennial artist, an American artist, a daughter, a sister, a healer. The idea of Black identity then becomes open rather than closed – all are invited into this celebration of a shared language, welcome to locate themselves at any point within this multiplicity of selves. After all, the word “vernacular†(the native language of a place) comes to us from the Latin vernaculus, meaning “household, domestic, native.†We are all native to a place, all with memories of home and family, all with those particular qualities, habits, and worldviews that we absorb from those around us.

I was curious to learn, especially in the context of this show, that vernaculus is the diminutive form of verna, which means “slave born in the master’s household.†For Black Americans, especially, home has both its contemporary meaning – the place where you were born, and its ancestral meaning – the home of your African ancestors, many who were brought to the United States by force and in chains. Pemberton’s work dwells in both these spaces: the former in two large paintings and the latter in two series of glass vessels titled “Ukhambas (spring)†and “Ukhambas (fall).â€Â

An ukhamba, the wall text informs us, “is commonly made from low fired clay and is used in the Zulu ritual of sharing sorghum beer.†The vessels take rounded, organic forms, some tall and elongated like eggplants, others short and squat like smooth pumpkins. The geometric, grid-like patterns of the ukhambas are informed by the woven sweetgrass of traditional Zulu basketry, and created in pleasing hues of seafoam green, goldenrod and white (“springâ€) and brown, yellow, orange, and ochre (“fallâ€). Topped with elegantly minimal brass lids, the vessels become functional jars – assuming a domestic purpose elided by the merely decorative vessels that populate so many glass exhibitions.

As if to prove the point, one of the ukhambas makes an appearance in Pemberton’s mixed-media painting “The Collector #2†alongside other containers, canisters, and baskets filled with patterned blankets. Pattern, in fact, is everywhere in this domestic portrait of a Black man in his living room: in his clothing, his armchair, the nearby footstool, the rug, the carpet, a piece of fabric affixed to the canvas. Paintings hang on his wall, salon-style; a floor lamp and a hanging light fixture in the shape of an owl suffuse the room with a warm glow. The ukhambas become part of the material culture, particular to an ethnicity and class and place, but also ecumenical – anyone can relate to stuff, the objects we surround ourselves with, the things that bring comfort in their familiar presence.

Therman Statom offers a different interpretation of home in “Marzo,†a small house constructed of two tall, slender boxes of translucent orange plate glass joined at a right angle and capped with two steep roofs. Rectangular sections of clear glass allow us to view an interior of mirrored shelving, glass balls and cubes, a miniature blown glass pitcher, and a wall collaged with the index from an atlas. Placed on a pedestal about a foot off the ground, “Marzo†requires that even shorter visitors crouch to look inside, evoking a feeling of playfulness as one gets closer to the ground, to a child’s eye level.

“Sol†and “Aqua Fuego,†two of Statom’s other works in the show, resemble oversized blown-glass heads, laid on their sides like fallen relics (or, the catalog text suggests, BrâncuÈ™i’s “Sleeping Museâ€), with rudimentary, bas-relief lines for mouths, noses, and eyes. Statom applies yellow and blue pigment unevenly, obscuring the clarity of the material. Scattered over the surface, scribbled lines of contrasting pigment feel like a gleeful indiscretion, as if an unattended child had vandalized the works.

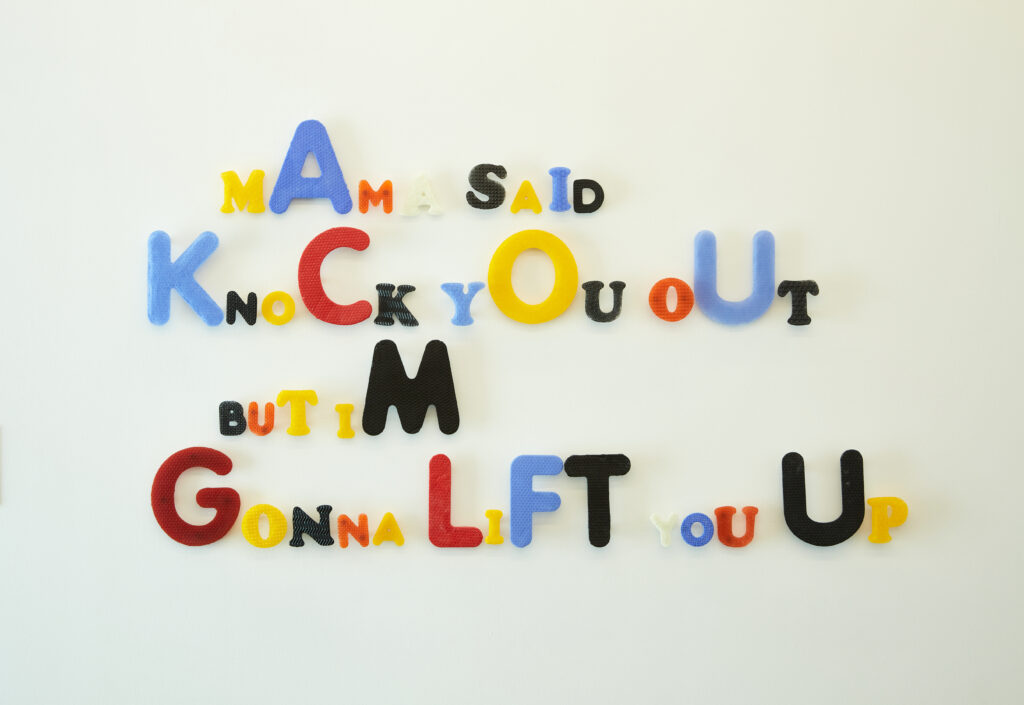

The primary colors and forms of childhood are picked up by SaraBeth Post in a series that uses cast glass in the nubbly textures of a toddler’s foam playmat. Variously sized capital letters are mounted on the wall in a range of depths to spell out words (“ACCOUNTABILITYâ€) and phrases (“JUSTICE IS NOT A FADâ€) germane to the current moment in Black American society; another in the series, “Remix #1,†adds her own spin to the LL Cool J hit “Mama Said Knock You Out.†By rendering elements of Black culture in the visual vernacular of childhood, Post locates a universal spirit that is optimistic, uplifting, and youthful.

The show’s theme finds more literal expression in the work of Leo Tecosky, who borrows elements from the exuberant Wildstyle form of graffiti and translates them into three-dimensional form. “Green Flourish,†for example, recreates the central mark in translucent, pale-green blown glass and completes the symbol with a fluid flourish of orange steel mounted to the gallery wall – street art becomes high art. Wet-looking drips of spray paint create the sense that we are encountering a piece just after the artist has fled the scene, heightening the often-illicit nature of the art.

Graffiti is a highly specific vernacular driven to its most specific, peculiar not just to a region or city, but to a specific neighborhood, seen only by those who walk it daily, who know its streets and alleyways intimately. In the Black neighborhoods of older U.S. cities, a church was often a cornerstone, complete with its own traditions of language, ritual, and dress. In Nate Watson’s installation, “Come Hell or High Water,†two stained glass windows are situated at 45-degree angles to the floor, parallel to each other, the arched points of their upper panes directed to opposite sides of the room. Videos of farmland at sunset and crowds of protestors are projected onto the walls that surround the windows, suggesting a narrative of collective strength, solidarity, and spirituality.

Nearby is Ché Rhodes’ installation, “Labor,†in which delicate blue glass bottles stand on a conveyor belt headed for a tall white chute; a clear glass portion at the bottom reveals a small pile of shattered blue glass. A pedestal in front of the contraption holds a round red button and a sign advising visitors that each piece of handmade glass represents a pledge of $60 to Crafting the Future; by pressing the button, a piece will be destroyed and a pledge eliminated. (Crafting the Future is a non-profit organization started by Corey Pemberton that supports BIPOC artists in the fields of art, craft, and design.) It’s smart, darkly funny, and ultimately heartbreaking, the wryness of the conceit a pale mask for the way the tireless labor of mass portions of the global population is regarded as disposable – destroyed with the mere press of a button, deployed as a joke.

Rhodes finds a lighter humor in “Flex,†a quartet of goblets and shallow bowls executed using the highly difficult reticello glassblowing technique, which creates an exquisite mesh pattern with a tiny air bubble suspended inside each diamond shape like a miniature pearl. But rather than finishing these forms with traditional glassware stems, Rhodes affixes them to models of flexing, muscular arms cast in muted black, red, and ochre glass. The blown glass is undeniably stunning (the model’s biceps are similarly impressive), and the artist is clearly enjoying this boastful intersection of the glass and Black vernaculars. If “Labor†is a critique of exploitative practices, “Flex†is a celebration of those arduous challenges we set for ourselves – the endless refinement of technique, the unending quest for perfection, the ceaseless search for the ideal form – all for that rare and elusive feeling of self-satisfaction, that private vernacular of joy.

Crafting the Vernacular continues at KMAC Museum (715 West Main Street, Louisville, Kentucky) through April 3, 2022. Top image: An installation view of Crafting the Vernacular at KMAC Museum (courtesy of KMAC Museum). Various artworks that range from two-dimensional painting to three-dimensional sculpture are on view in a gallery with white walls. Photo by Ted Wathen.