The first song Patrick McNeese ever wrote, he told an interviewer in June 2011, was “Dreams in the Light.†Its piano accompaniment is wistful and searching, conscious of struggles to come and already resigned to them. Its cryptic first lines, like the lyrics of so many of his songs, are unmistakably ominous and world-weary:

Information

Manipulation

Keep your eye on the bouncing ball

The situation

The frustration

Don’t you get it?

We rise and we fall, y’all…

In the audio recording of his thoughtful, candid chat with Beatriz Colonia of the nonprofit group StoryCorps, which conducts interviews with everyday Americans around the country, McNeese explained the song as a sort of early premonition of the career he would go on to have as a unique, all but unclassifiable singer-songwriter, poet, visual artist and filmmaker in Lexington. “I recognized early on that there was a mountain to climb here,†he told Colonia. “If you’re going to stick to this, you better be ready for some unfriendly circumstances.†What unfriendly circumstances? For one thing, he was never able to make a living solely from his music and art in a city where his supporters were staunch but never especially numerous, which forced him to rely on a variety of “micro-jobs†and side gigs, including production design on commercials and local independent films including The Congress of Wonders (1994) and 100 Proof (1997). “For the few who get to the top of the mountain, it’s great,†he said. “But there’s a lot of people down the mountainside.â€

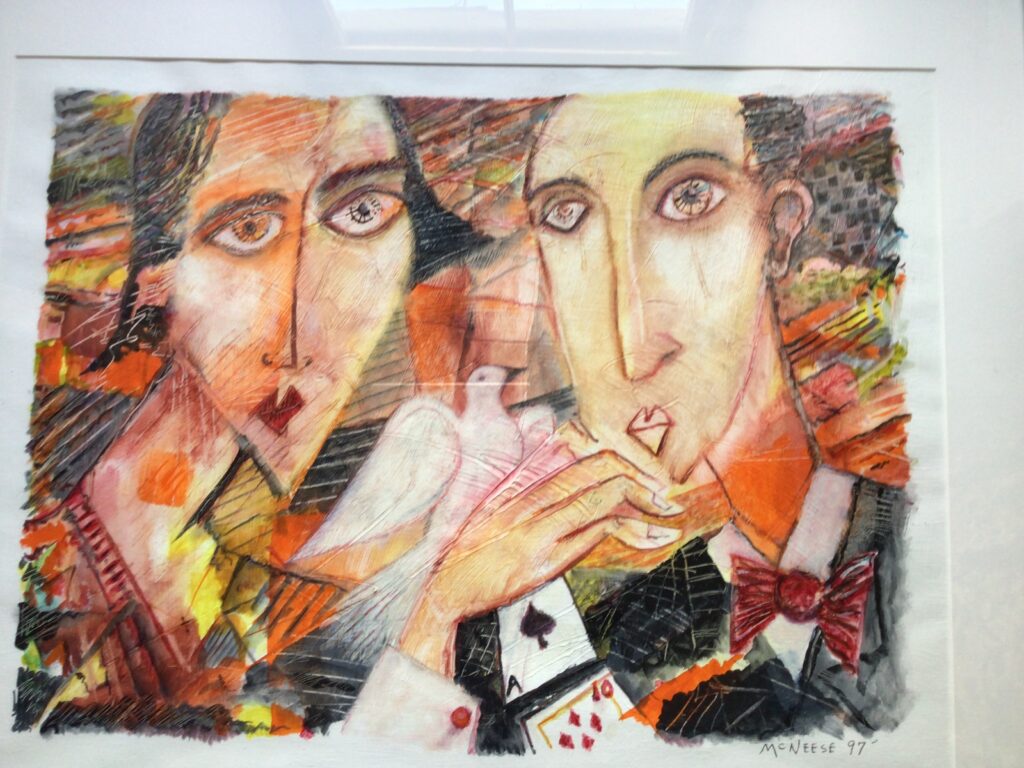

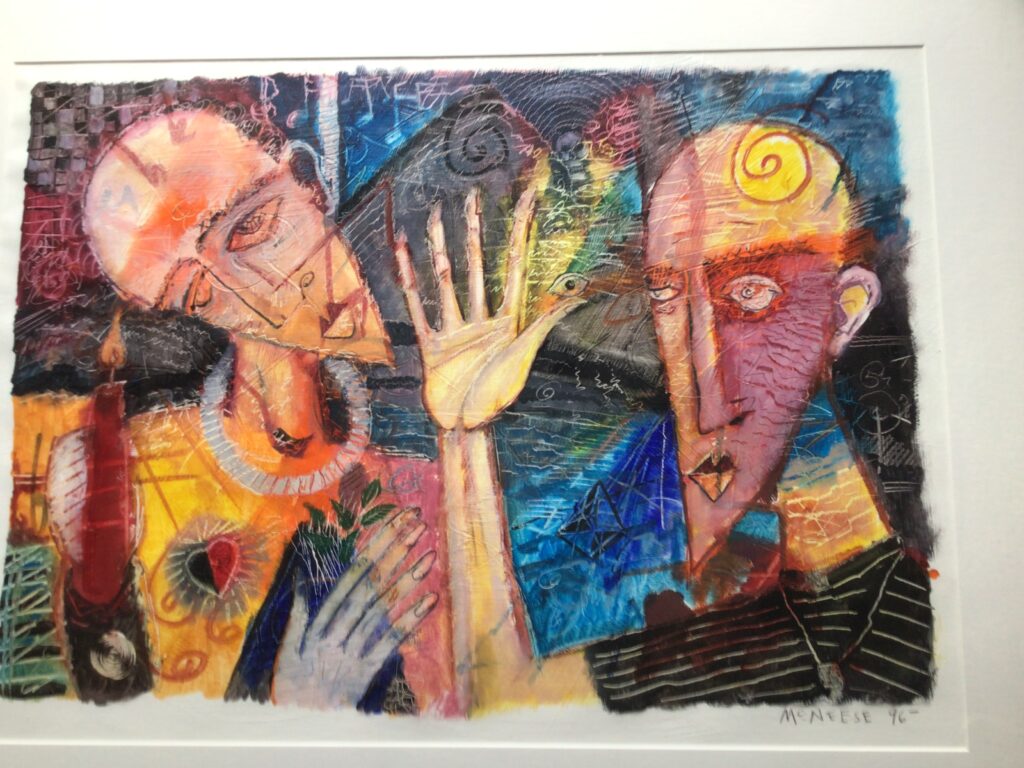

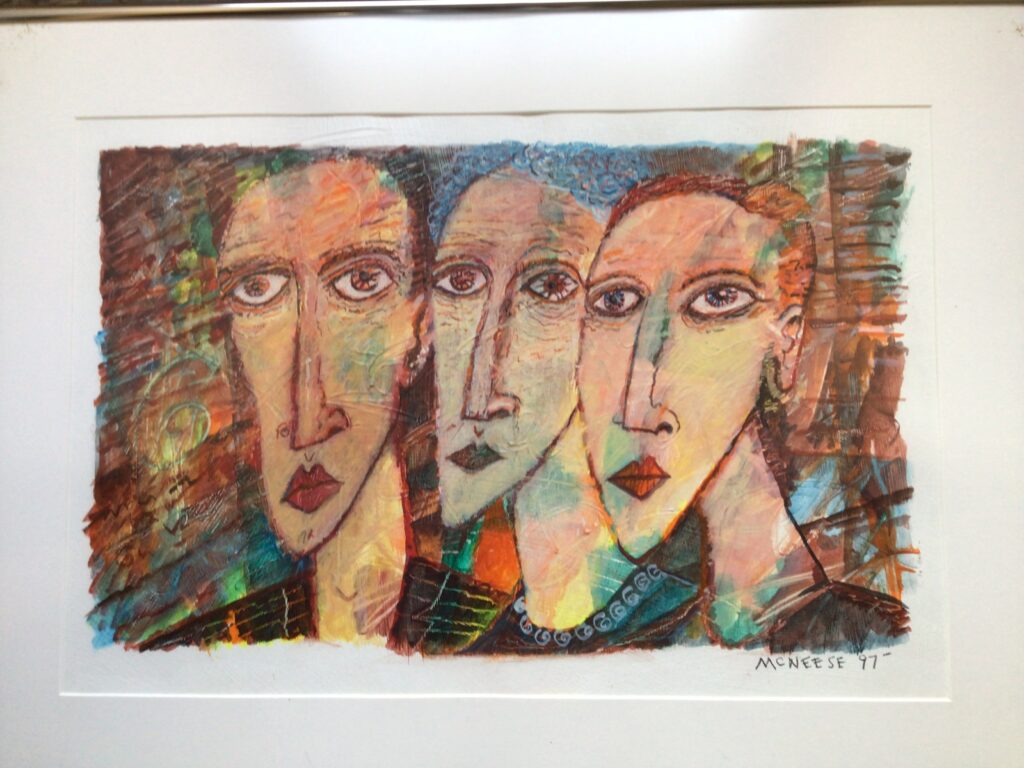

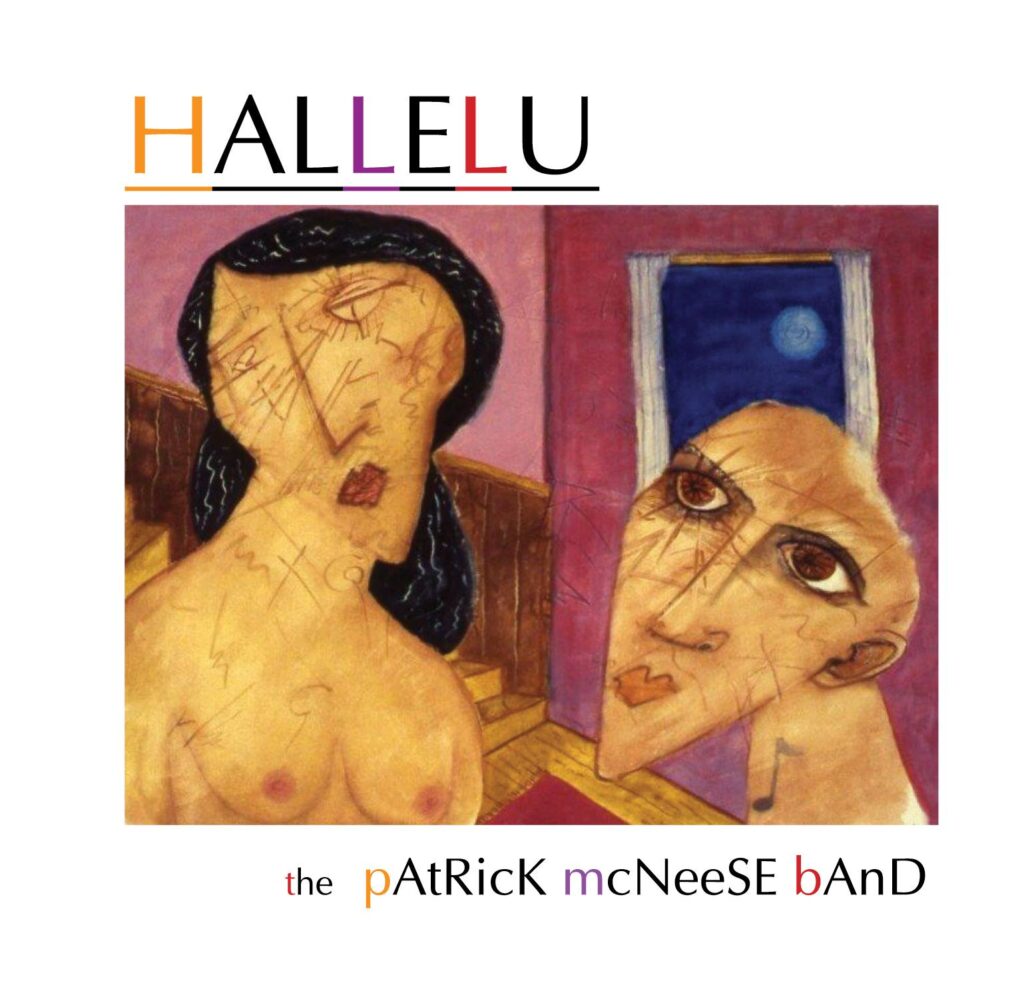

McNeese, a funny, philosophical, politically engaged, and highly intelligent man who died of complications of cancer last December at the age of 68, spent most of his life in a Sisyphean struggle on that mountainside, rising and falling. A third-generation Lexingtonian, he earned an art degree at the University of Kentucky before launching himself as a neo-Expressionist painter and mixed-media artist specializing in distorted cityscapes and stylized portraits of elongated, pointy-chinned faces influenced by the work of Max Beckmann, Picasso, Chagall and other European artists of the 1920s and ’30s. He gained a measure of regional recognition for his paintings, exhibiting widely and securing gallery representation in Louisville and Cincinnati, but remained unimpressed by the prospects for visual artists locally. “In Lexington, there’s not a gallery system,†he told Frances Figart of Business Lexington in 2012. “You come in and there are a few galleries, but it’s not New York City, it’s not San Francisco, it’s not Chicago – even Asheville has a better gallery system. The problem is a lack of audience, and in the visual arts sense it’s a lack of purchasing audience.†By the time of that interview, in fact, McNeese had long since largely given up painting to concentrate on music (though he continued to market his visual art, some of which he used on his album covers, for the rest of his life). “Even when he was painting, he was always playing music, and especially after 2000, that really took up most of his interest,†said his widow, the painter and retired chef Claudia Hatfield. “Writing it, rehearsing it, trying to get it produced – all of that took a lot of effort. Music was part of him, and that continued through his whole life.â€

Unlike his brother Barry, who built a successful career as a bass guitarist in Europe, McNeese stayed in his hometown – living for decades in a downtown apartment at Short and Upper with Hatfield, his beloved beagle Sophie and, later, a terrier mix named Lola, from whom he was inseparable – and became a fixture on the local music scene. He got his start as a peripatetic dinner musician, first at Alfalfa on South Limestone, where he enjoyed hanging out in the alley between sets. “With his understated manner, quick wit, and endless knowledge of esoteric topics, he fit right in with a motley group of overeducated antiestablishment types trying to forge an alternate path in Lexington,†his friend Ginny Daley recalled at a memorial service in the State Theatre. “He was a true renaissance man.†(In a story that has become semi-famous, McNeese, Celeste Lewis, and her brother Bruce were once shushed by an annoyed waitress at Alfalfa for laughing too loudly for too long. “Patrick was one of the funniest people in my whole life,†Lewis recalled. “He and Bruce were riffing at the table, pretending to do jokes for vacuum cleaners making me laugh so hard I couldn’t get my breath. The waitress said, ‘You guys are having a little too much fun.’â€) In later years he found regular gigs at Natasha’s, Henry Clay’s Public House, and other restaurants, hotels, and nightclubs.

“He was a son of Lexington,†said his friend and bandmate Tom Martin, who is also an editor at UnderMain. “I can’t imagine Patrick would have taken his art anyplace else.†He recorded several albums of his own songs and, since forming the Patrick McNeese Band in 2013, recorded three more CDs with that group, singing and playing guitar alongside Martin on keyboards, Jesse Pena, and F. Miles Hanchett on bass (Jesse later became lead guitarist), Tripp Bratton on drums, and Maggie Lander on violin and vocals. Earlier versions of the band featured Logan Lay and Scott Stoess on bass.

But McNeese’s musical appeal and reach were limited by his being anchored in Central Kentucky and, more important, by the fact that his hybrid music – a moody, discursive blend of mellow jazz, wailing blues, arty ’70s pop and rock, and rootsy Americana that McNeese, when pressed, called “Appalachian jazz†– didn’t fit into any easily defined category or genre. “We’ve often had people come up to us and ask, ‘What kind of music is this, anyway?’†Martin said at the memorial. “We didn’t know.†As McNeese said in the StoryCorps interview, “The harder you are to classify, the more dependent you are on a smaller but more devoted group of people as your audience, and they appreciate your uniqueness.†In a city where many of the most commercially successful musical acts play straight-up country or rock ’n’ roll, Hatfield says, “People didn’t always get Pat’s music.â€

This wasn’t lost on McNeese. “He was the epitome of someone who chooses to devote his life to art in a market that was not supportive of that,†Martin said. “I think he was disappointed that a town that views itself as culturally sophisticated, compared to other communities in Kentucky, but doesn’t always step up to the plate.â€

Not that it kept him from creating. “He was an optimist and just kept working,†Hatfield said. “He believed in what he did.†His sister, Kathleen McNeese Quigley, agreed. “If he was frustrated, he didn’t live in that frustration. Early on, he might have considered moving to a larger city, but he really loved Lexington and wanted to progress the arts here. And he was very true to the art itself. He wasn’t going to go to Nashville and do country music.â€

However much it cost him, McNeese’s musical independence was a point of pride. “When I create music, I almost consciously try to steer away from a particular stylistic channel and get to another place,†he said in the StoryCorps interview. “On a good day, I innovate. On a bad day, I slip back into . . . whatever.†As a rhythm guitarist, he drew on multiple influences, from the Count Basie Orchestra’s Freddie Green to Joni Mitchell. “He played the guitar like a drummer,†Martin said. As a self-taught pianist, McNeese relied on jazz chords and improvisation à la Keith Jarrett and George Winston. (He often couldn’t, or wouldn’t, reproduce or cover preexisting tunes such as jazz standards. Occasionally filling in a hotel cocktail lounge in Lexington, he recalled, “I actually took the tip jar off the piano because I didn’t want people thinking that if they gave me a buck, I’d play a request. . . . It’s the dilemma of the artist. You’re doing your own thing, but you’re afraid that you’re not going to be able to satisfy your audience, which has been a theme in my life.â€) His method of collaborating with his band members was generous and non-controlling – “a circulatory system of give and take,†as Hatfield put it – that allowed each player to contribute in his or her own way. “He gave you a platform to find yourself within the music he would write,†Bratton said at the memorial. “He wasn’t possessive,†added Martin, “and that’s what kept us coming back.â€

McNeese’s lyrics, stitched together from ideas and imagery collected over periods of up to a decade (a process he described as “assembling little scrapsâ€), usually resist linear storytelling in favor of an impressionistic approach in which the listener is required to connect the dots. His songwriting “leaves spaces and makes leaps that people wouldn’t stand for in regular conversation,†he commented to Colonia. “It wouldn’t make sense. But in a song or poem, we allow that to happen. And then we fill in the meaning.â€

The meaning is often quite dark. For every rollicking, relatively upbeat tune like “Howl†(which you can hear in a live performance from Natasha’s on McNeese’s website, thepmband.com), there are songs full of undercurrents of desolation and regret. “Bought and Sold,†played at his memorial at the Kentucky Theatre, opens in the haunted, haunting voice of a man filled with resignation and something like bitterness at what he seems to regard as his small but still pre-programmed life:

I work in a parking lot

And I guess I drink a lot

It seems to get me through here

And I smoke those old cigarettes

And I love to place a bet

There’s not a lot else to do here

And I’m just doing what they told me

Can’t you see they bought and sold me?

Yet however forlorn, the songs are finally life-affirming and life-giving – the testimony of a man who did it his way, without fear or compromise, and who was grateful for the chance. “The artist is lucky,†he shared with Colonia. “You get to lay hands on the heart of the matter, I think. And you can be unique. You don’t have to follow the template.â€

McNeese stuck to those principles in the final year of his life, when he knew he was dying. With renewed purpose last fall, he returned to the studio – and to his roots on the piano – to make a series of spare, heartfelt recordings of a final group of songs, all of which can be streamed for free on his website. “It was a bit more of an intimate project due to his state of mind, his state of health, but it turned out to be very joyful,†said his longtime producer, Duane Lundy. “I know it’s supposed to be sorrowful and sad, but I laughed the majority of the time. The material just flowed right through him.†About ten days before he died, he told his sister-in-law, Paula Hatfield, that he had no regrets about his life. “He had been able to do everything that was important to him,†she said at the memorial. “He was only sad that he had to leave Claudia, his family, and all who were part of his life.â€

One of the songs McNeese chose to record in those final sessions with Lundy is “Dreams in the Light,†which, after its opening notes of frustration, settles on a call for artists to pursue their personal visions despite all the rising and falling to come.

I believe that we are angels

Somehow we got lost

We got dangerous

But stay in range of us

Put no name on us

Keep your dreams

Keep your dreams

Keep your dreams

Keep your dreams in the light

“It was good advice to myself,†he told Colonia. “Art is really just a tool that helps you live your life. It’s not an occupation. It’s an avocation. And I’ve kept my dreams in the light.â€

Link to Patrick McNeese’s last recordings, “Dreams in the Light” (2021): https://thepmband.com/album/2157696/dreams-in-the-light-2021