The only way for a woman, as for a man, to find herself, to know herself as a person, is by creative work of her own.

— Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (1963)

There are all kinds of royalty, all kinds of ways for artists to indicate what makes them stand out from the rest of us mere mortals, and all kinds of reasons – personal and political – for doing so. Hans Holbein the Younger’s famous portrait of King Henry VIII (1536-37), in which a virile, all-powerful colossus of a monarch famously gazes directly at the viewer in sumptuous royal regalia, was meant to bamboozle diplomats visiting the Tudor court, distracting them from the corpulent, ailing ruler he actually was. A few centuries later, the contemporary African American artist Kehinde Wiley has forged a major career with his heroic portraits of latter-day Black royalty – including basketball stars, entertainers, and former President Barack Obama – that convey their vaulted status with the help of highly decorative, often floral backgrounds.

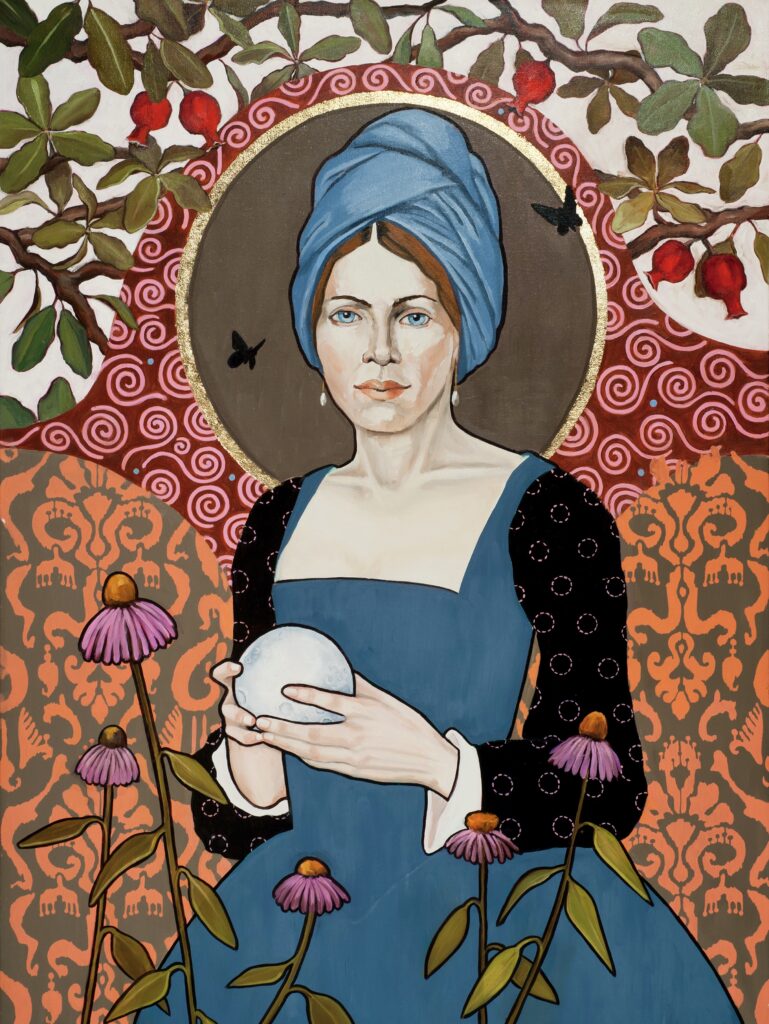

The Lexington artist Honora Jacob seems to be taking her place on this continuum in “Myths, Legends and Lore,†a striking set of twelve oil-and-gold-leaf portraits of women of history and legend at the Lexington Art League (LAL) through April 15. Like Holbein, she understands the power of the direct, largely straight-on, essentially confrontational gaze. And like Wiley, she appreciates the ability of classic endpaper, wallpaper and textile designs (of the sort associated with William Morris, among others) to convey richness and complexity and add visual interest. (Jacob seems to agree with Georgia O’Keeffe, who once described her art practice as “filling a space in a beautiful way.â€) To these influences, she has added certain tropes of medieval, Renaissance and Byzantine art, in particular luxurious gold leaf and icon-like spheres that frame the faces in most of these portraits. Divinity is not implied here, presumably, but perhaps something like sainthood, even a kind of queenship, with or without geographical realms to rule.

The crowns that Jacob’s subjects wear are alternately literal and figurative. In the first category are two officially designated queens of England a few centuries apart, both named Elizabeth. In the second category, the women’s regal status is technically invisible but strongly conveyed by their air of self-confidence and their piercing, sometimes haunted, often quite steely gazes. Their substance and authority derive not from their birth but from their evident defiance of gender norms in pursuit of achievement in battle (Joan of Arc), espionage (Isabelle de Limeuill and Louise-Renée Marguerite de Penacoët, who spied for Catherine de Medici and Louis XIV, respectively), aviation (Amelia Earhart), and sharpshooting (Annie Oakley), among other fields of endeavor historically dominated by men.

How they’re dressed and what they carry – the go-to signifiers in portraiture since the cave drawings – are vitally important here. In “Coronation Day†(2019) and “HRH The Queen Bee†(2022), Jacob’s queens are resplendent, as you might expect, but so are all the others here, in their own distinctly stylish, sometimes surprising, sometimes anachronistically stylized ways. The teenaged warrior in “Joan Amid the Narcissus†(2020), often depicted in mail and armor, appears here in a chic black garment of vaguely Asian design, a pale blue ribbon flowing around her neck as if to remind us of her youth; it’s the sword she brandishes and the preternatural calm in her eyes that tell us what she’s capable of. In “Annie & The Ace of Spades†(2021), Oakley is in full entertainer mode in a color-blocked outfit in two tones of blue, the brim of her fawn cowgirl hat framing her pert yet implacable face as playing cards orbit her like planets in a solar system. In “Jeanne’s Circumnavigation 1769,†the outfit worn by Jeanne Baret – the first woman to sail around the world, as we see from the compass she carries – is that of an elegant, slightly rakish man; she disguised herself as such because it was illegal in those days for les femmes to be on expeditions. (On one of them, she discovered bougainvillea.) Earhart, in “Amelia’s High Flying Dream†(2022), is instantly recognizable from her period aviator cap and goggles, and the model airplane she’s cradling like a baby in her arms seals the deal. For sheer fashionista fabulousness, “Belle Marguerite†(2019), in which de Penacoët shows how she fascinated two French monarchs, among others, can’t be beat.

Three works in this series stand out in their own ways. “Celeste Amid the Coneflowers†(2020) depicts not a historical figure but one from mythology: Celeste (also known as Selene), goddess of the moon, looking eminently human, even earthbound, despite the fact that she’s holding the moon itself in her hands. And in “Cross-Continental Companions: Lady Ellen and Montana Girl†(2022), Jacob’s roots (she’s a Texan who moved to Lexington three years ago) come through with joyful brio. The painting shows Nan Aspinwall, aka “Montana Girl,†and her horse, Lady Ellen, on whom she rode across North America, becoming the first woman to do so in 1910-1911. Elsewhere we find “Buckaroo Jane: Rodeo Queen†(2022), a portrait of the female bronc rider and 2016 Miss Rodeo Virginia, Jane Revercomb.

The backgrounds in these works often feature elements from the worlds of interior design and gardening, both traditionally associated with women. While the faces and bodies in these paintings are rendered more or less realistically, the costumes and backgrounds are flat and graphic in a way that feels closer to contemporary abstract painting than to traditional portraiture. Pomegranates and other fruits dangle from the trees above, while flowers (sometimes including bulbs, roots, and all) seem to levitate up from the ground, suggesting fertility, harmony with the natural world, and a kind of magic – not the domesticity-centered feminine mystique once debunked by Betty Friedan but an older, deeper, more elemental force, the feminine psyche untrammeled by the male gaze. Collectively these portraits convey the artist’s sense of what a woman is, or can be, if left to circumnavigate the world for herself. In these paintings – and, perhaps most important, in the act of making them – Jacob is providing some answers.

Top image: A photograph of three paintings by Honora Jacob hanging on a white wall at the Lexington Art League. Photo by Kevin Nance.