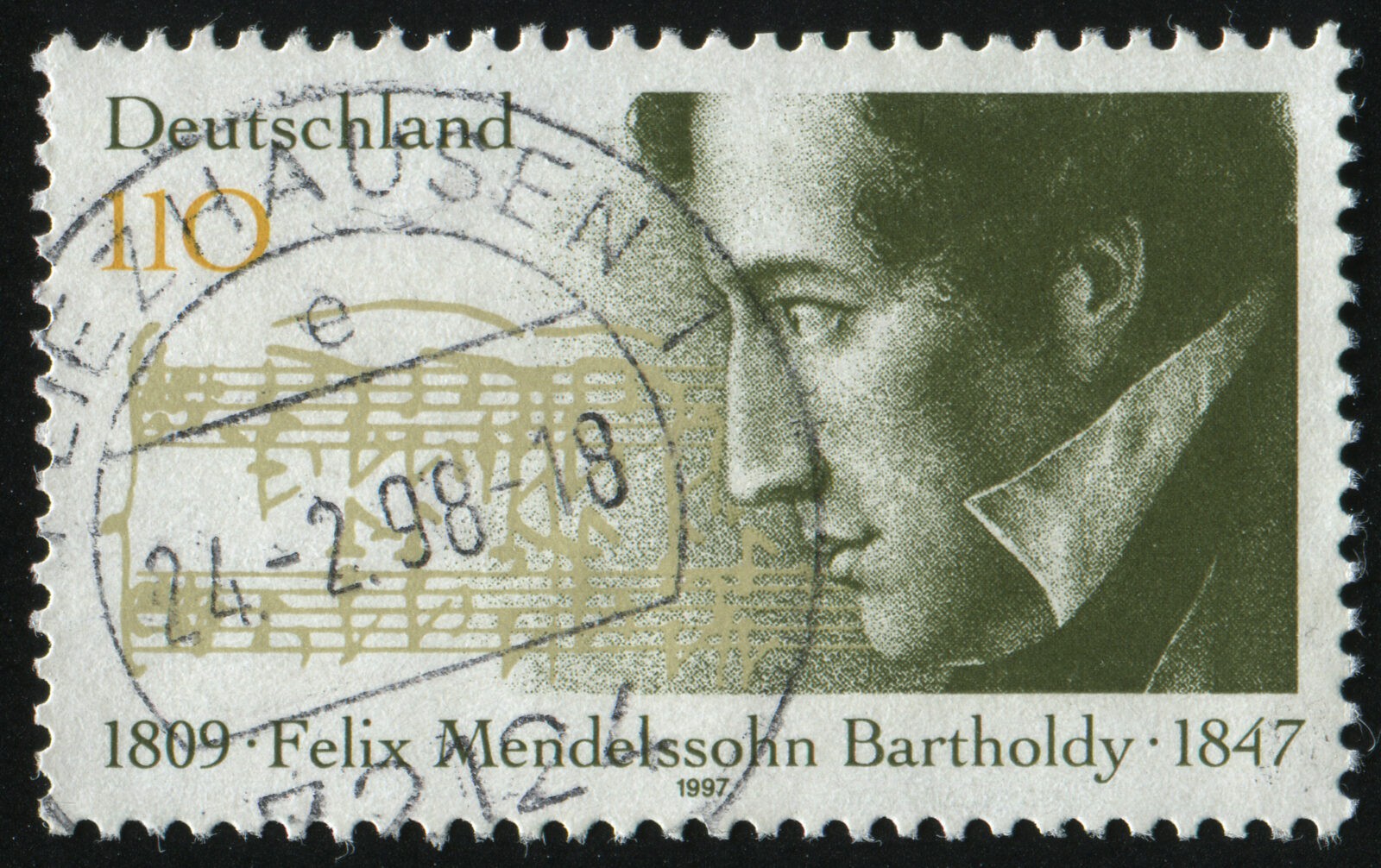

The Lexington Philharmonic continues the season November 13 at the Singletary Center for the Arts with Mozart and More. As the title indicates, the centerpiece of the evening is Mozart’s magnificent, mature and oft-performed 40th Symphony. Referred to many times as “the Great G Minor symphony,†this classic piece, composed near the end of Mozart’s 35-year life, stands in contrast to his 25th symphony, “the Little G Minor Symphony,†his only other symphonic work in a minor key. For this performance, Amadeus Mozart is in the company of  Felix Mendelssohn, Dmitri Shostakovich and John Corigliano.

Joining UnderMain contributor Chip Sebastian for a chat about Mozart and More and the experience patrons can anticipate is LexPhil Conductor, Scott Terrell and musicians Stephen Campbell and Pei-San Chiu.

UM: Mozart and More. Just the title makes me curious. Why “More?”

ST: As ever, we’ve tried this season to offer a wide range of listening, showing many aspects of music and the wide range of the Lexington Philharmonic. In the course of a season, we wanted to establish a balance. We did Mahler, then went American with Time for Three. There are moments when we want to feature our artists, and this upcoming evening is certainly one of those times.

UM: If you needed a word to sum up the entire evening, what would it be?

ST: If I had to sum it up, it would be “Voyage.”

UM: Why “Voyage?â€

ST: Well, the Corigliano piece itself is entitled Voyage, for starters. Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture is one of his finest works and it was composed while he was traveling through the Hebrides Islands. The whole evening has the sense of taking a journey.

Hebrides was composed by Felix Mendelssohn in 1830. Also known as “Fingal’s Cave,†the work was inspired by Mendelssohn’s trip to Scotland. The ten-minute piece, an overture, was dedicated to Frederick William IV, then Crown Prince of Prussia. The work was revised by Mendelssohn at least once after its premiere in London, and has been featured in many literary works and films.

UM: Hebrides is the first piece on the docket, correct?

ST: Yes. This is one of Mendelssohn’s most beautiful pieces. Dark, rich, and very different from say, Shostakovich, who can be very angular, percussive, dissonant.

UM:Â Mendelssohn always seems rich and textured.

ST: Yes. Like most composers coming from the Romantic Era, he has a full, rich sound. Emotional.

UM: A contemporary of Beethoven.

ST: Yes.

UM: It seems the programs are trying to balance the more harmonious with the more dissonant. Would that be fair to say?

ST: It’s more of a thematic thing. What pieces fit together to make a very interesting and dynamic evening. Like a good meal.

UM: Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No. 1. Another interesting piece.

ST: Shostakovich will bang you over the head, while the others draw you into their worlds.

UM: This first piano concerto was completed in 1933, not so long after the Russian Revolution.

ST: Yes. Shostakovich had a bit of a slap on the wrist from the Russian aristocracy about an opera he had done not long before. He was trying to stay in good graces with this piece.

UM: He was well-established by then?

ST: Yes, but in the 1930s, he was still uncertain about being a pianist. Perhaps not as settled as later in his career.

UM: The pianist and the trumpet have major roles here. The featured pianist: Fei Fei Dong. Tell me a bit about her.

ST: Fei Fei was one of six finalists in the prestigious Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. She studies at Julliard and she has had nothing but glowing reviews from the many places she’s played. Her pedigree is very good. This is a real tour de force for a pianist. She’s a young and fresh talent and we’re glad to have her.

UM: The other featured performer, trumpeter Stephen Campbell, plays regularly with LexPhil?

ST: Yes, Stephen’s been around for awhile and he’s another wonderful talent.

UM: Do you feel there is a great story between the piano and trumpet?

ST: Absolutely. Certainly the pieces of this season have a protagonist and antagonist. Story is what makes it all interesting.

Stephen Campbell is the Principle Trumpet with LexPhil

UM: Stephen, what is your sense of the structure and power of this Shostakovich piece?

SC: The Concerto is a wonderful composition on so many levels. It’s one of the first major concertos to come from the Soviet era. Shostakovich was constantly falling in and out of favor with the Soviet censors based on their standards of decorum and aesthetics. One moment, he’d be awarded the coveted Stalin Award, the next he’d be publicly criticized. This is one of the compositions which brought him back in favor.

UM: Because of the focus on trumpet, is this a piece that trumpeters look to as a standard for performance? Something every trumpet player wants on their resume?

SC: The concerto is great for trumpeters because of the dramatic range required for performance. We have everything. The character of the second movement is really low. Someone, bourbon in hand staring off into the middle distance, contemplating life. There’s a real folksy section in the fourth movement, as well as a quotation from one of my favorite Haydn sonatas and a very exciting finish.

UM: You seem to be quite at home playing with LexPhil.

SC: Performing with the Lexington Philharmonic Orchestra is a thrill. I love performing high quality music with friends and colleagues.

UM: Thank you, Stephen.

SC: Thank you.

Resuming with Scott Terrell, we move to John Corigliano

UM: John Corigliano is a name perhaps unfamiliar to many.

ST: Yes. He’s probably most famous for the score to the film, The Red Violin, which featured Joshua Bell on violin.

UM: Great movie.

ST: Yes. John’s very prolific and Voyage is an early piece that demands a great principle flute and we certainly have one in Pei San.

Pei-San Chiu is the principle flute for LexPhil and is featured on Voyage.

UM: Pei-San, what are your thoughts onVoyage, in terms of the flute and the level of performance required?

PC: Voyage is the instrumental version of Corigliano’s choral work based on Baudelaire’s L’Invitation au Voyage. The timbre of flute and strings is very warm and comforting, which gives a new texture and atmosphere to the piece, just as it’s said in Richard Wilbur’s translation, “There, there is nothing else but grace and measure, richness, quietness and pleasure.”

UM: Wonderful to imagine. You’ve been with LexPhil for some time, haven’t you?

PC: I joined LexPhil in 2013 and this is my third season. It’s been such a pleasure to be in the LexPhil and work with my colleagues.

UM: It seems LexPhil has a wider range of endeavors with each passing season.

PC: Thanks to Scott, we’ve done so many great concerts with superb soloists, including classical, opera, film music, works with choral and Pops. As a flutist, I couldn’t be happier to play good music with my colleagues.

More on Voyage from Scott Terrell

UM: Voyage seems to be quite a contrast to Shostakovich.

ST: Exactly. John has done some of the most beautiful music for strings in the last few decades. This is a very warm piece and will work nicely after the dissonance of the Shostakovich. Compositionally, you hear a lot of Barber, Copland and Bernstein in John’s music.Â

UM: When you have a piece like this, with the artist still living, do you ever have interactions or brainstorming with the composer about the work or the performance of it?

ST: In this event, no. It’s interesting with composers: you never know if they are watching musical scenes around the country and the world to see if their pieces are being played.

UM: I suppose this would help keep the performance true, not knowing if the person who gave birth to the piece is watching and inevitably critiquing the performance.

ST: There is a sense of being true to the work and its composer.

UM: I know this is true with writers, when films are made of their books. There seems to be an understanding that the message or theme of the work, the writer’s original intent, is preserved.

ST: Yes. One can’t help but think about that when a performance is developing. I’ve done some of John’s pieces before. Gazebo, and The Red Violin. It’s all very listenable stuff, very pleasant to the ear.

UM: Do you ever wish you had the artist on standby when you perform pieces by living composers?

ST: That’s always nice, if possible. So often it’s not. I did meet John many years ago, when I was in Aspen as a student. Do I know if he knows the music’s being played? No. I had an experience along these lines with Jennifer Higdon, who is a modern composer, won many awards, etc. I was performing a piece of hers titled On a Wire with a group called Eighth Blackbird out of Chicago. I saw Jennifer at an event and introduced myself and she said Eighth Blackbird had been raving about the experience and she knew that we had performed it in Lexington. I was taken aback. You just never know who’s hearing what when.

UM: I know in dance the circles are pretty small. I would imagine the same is true in, especially, classical music.

ST: Yes. Definitely.

Mozart finished his 40th Symphony in 1788, along with the 39th and 41st in that same year. Even though the three final symphonies were written close together, there are marked differences between them. Mozart composed many other works after the 41st Symphony, “The Jupiter,†living another three years before succumbing to an illness at 35. Scholars still cannot agree on what actually killed Mozart, but it is well-documented that he was bedridden in his final days, and composing to the end.

UM: Mozart’s 40th Symphony is one of his best-known, most-beloved symphonic works.

ST: It’s the linchpin of the evening. Mozart in general is very different in terms of scale and performance. The sound is energetic and profound and really will make for a huge ending to the night. It’s important in any evening that we have that old performance idea of tension and resolution. The audience will certainly have enough tension with the Shostakovich piece with a little steam let off from the others. But the Mozart should really open the floodgates at the end.

UM: A lot of different styles in the evening.

ST: Yes, and the other interesting thing besides the difference in styles is that the composers are at different places in their lives.

UM: This was toward the end of Mozart’s life, but his life being so brief, he would have been approaching middle-age when this was composed, right?

ST: Yes. Noting his early death, there’s still a marked maturity in his later work. A lot more color and nuance that isn’t present to the same degree in the earlier, developmental material.

UM: It seems Mozart never stales, even two hundred-plus years later.

ST: It will always be great to hear and perform.

For information about LexPhil and tickets, click here.