The high quality of the Lexington Philharmonic continues with the upcoming production of the oft-played Rimsky-Korsakov classic, Scheherazade. Unlike many productions of well-known works, however, Scheherazade is being given the full treatment as a “Beyond the ScoreⓇ†production. The Chicago Symphony gave birth to the “Beyond the Score†idea and it has seen much success with many symphonies across the country. Here to talk with us about Scheherazade, “Beyond the Score,†and the value of the arts community in general is LexPhil’s music director and conductor Scott Terrell.

UM: Scheherazade. Well-known piece. Rimsky-Korsakov. Tell us about the piece and how the performance on February 5th will be different from the usual fare.

ST: It’s a great orchestral piece on a lot of levels. The story, which is from 1001 Arabian Nights, is always interesting. It’s a piece we’ve done before, but we were looking for something different.Â

UM: How is this different?

ST: It was some time ago when Chicago created “Beyond the Score,†with standard and non-standard pieces. They wanted to bridge the gap between a veteran concert-goer and a novice concert-goer. It’s a combination of music, actors, video, multimedia. There’s imagery that matches the story and the idea of the piece. The images and the context are both elucidated at the beginning. Some of these standard pieces are done many times in the same way which, over time, can be comfortable, habitual, but not really exciting, new or deeply interesting.

UM: What will this do for the audience?

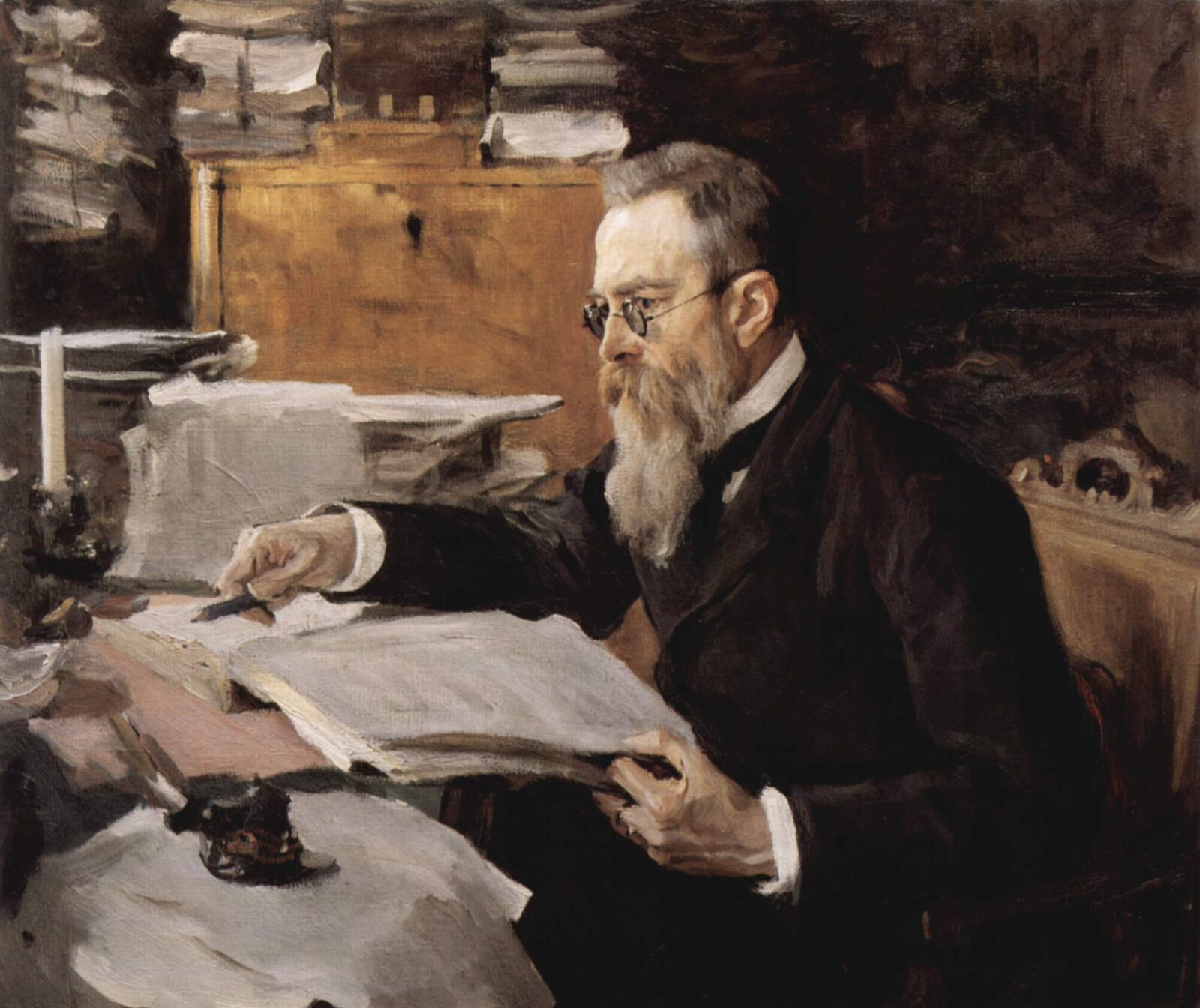

ST: It gives the musical context and illuminates the times that were going on to create such a piece. Many Russian composers were immersed in Arabian or Middle Eastern music at this time. Growing up in Russia at the time of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov meant being exposed to this other music that was coming in from far-away lands.

UM: What happens in the first part of the show?

ST: Two actors are involved. One is speaking the words of Rimsky-Korsakov, giving his influences and involvements, speaking in first person. The second actor has the storyteller role. This is the voice of Scheherazade, giving the four stories that eventually saved her life. These are 4-5 musical excerpts which last around 50 minutes, what I call a “dissection,†a piece of Scheherazade. After the intermission, we just play the piece and everyone has a context, an understanding of what made this piece come to be.Â

Scheherazade (view video) was the daughter of the Vizier of  (second only to) the King of Persia. When the king’s wife was unfaithful to him, he had her killed. He vowed never to be cheated on again and decided to marry a virgin each day and behead her the next, thereby never giving any woman a chance to make a fool of him again. Many women had been killed in this way, and when the king met Scheherazade, she was to be another victim of this madness. Scheherazade began telling the king stories, always stopping at dawn, each of the 1,001 tales buying her another day of life. By the time she had no more stories to tell, the king had fallen in love with her and she became his reigning queen.

UM: Do you find telling these stories in new and exciting ways is inspiring to your regular patrons?

ST: Absolutely. This puts new eyes on a classic work. For some, it’s a re-discovery, for others it may be brand new, but they are getting the context of the piece, which is more than likely much different than what people received and understood the first time. Scheherazade is one of those story pieces which is very special. In terms of how we present, the first half excerpts are not only from Rimsky-Korsakov, but from other Russian composers, peers of the time, and one can hear the sounds that influenced him through their words as well. This gives immense perspective as to how great the score is. It’s a wonderful, conceptual piece, and people forget how programmatic, but colorful, it is.Â

UM: Is it a much different experience for the Philharmonic in rehearsals, doing a well-known piece in this “Beyond the Score†fashion?

ST: This will be a different concert piece than what we’re used to. For the members of LexPhil, they have had an experience of not finding his words boring as musicians. We’re all reading through it, saying “That makes a lot more sense now.†If you’re an arts or musical nerd, it’s fascinating to think of how someone comes up with this stuff and “Beyond the Score†has helped to shed light on that for the orchestra, as it will for the viewers.

UM: Is it important to stick with classics from an artistic perspective? I know financially it makes sense, but when preparing the season, and piecing things together?

ST: It’s important to combine the known with the unknown. Most people know this work, so it is known. Doing it the way we’re doing it, though, will be an unknown to everyone. To me, this is much more exciting. There’s always a deeper appreciation when a piece is juxtaposed against something else, particularly the history. “Beyond the Score†has allowed us to juxtapose the piece against itself, in a new and different way from the usual. It is also important to juxtapose one piece against another on a given evening. In April, for instance, we have the Dvorák Symphony No. 9, “New Worldâ€, which is a very well-known work. It will be contrasted that evening with the world premiere of Avner Dorman’s After Brahms, as well as  Dorman’s Frozen in Time percussion concerto. This will make for a very interesting evening. Known and unknown. Part of the fun is the “I don’t know.†Like I said, the audience may love it or they may not. You have to take a calculated risk as an artist. One never grows through staying comfortable, staying status quo.Â

UM: What we’re talking about with “Beyond the Score,†putting together known works in as-yet-unknown ways: is this trending with other orchestras striving to be new and cutting edge?

ST: Yes. This is one of the things at which modern orchestras have become very adept, with Chicago leading the pack: a way to reach out and engage the audiences. How can we get more people into the hall? I’m very proud we’ve come along this path by responding to the audiences. How can we build and grow and give our audience something meaningful? Rather than orchestras reacting to a bad year or season of low attendance after the fact. It’s much better if we are proactive. Find out what people in 2016 are wanting out of their Philharmonic. This idea is being used all over the country with great success.Â

UM: Particular to Rimsky-Korsakov’s work in general, do orchestras look forward to doing it? Is it a favorite?

ST: From Rimsky-Korsakov’s perspective, this sound defines him. Most people will tell you he was one of the greatest orchestrators to ever live. He actually wrote books on orchestration. Because he really knew what he was doing, it always makes it a great pleasure and challenge for orchestras to come together on it. It’s good for the orchestra, too. They realize it’s a big chunk of music, not just this piece, but everything in the program. It’s always important that there’s perspective. As a conductor, I try to constantly listen with “new ears†and see the old and new influences and perspectives. What’s tricky about Scheherazade, mainly because it’s such a complex orchestral work, is that the brilliance of the piece begs the questions, “Why did it come about? What was going through the composer’s mind?†This is something the “Beyond the Score†process can answer and that informs the entire experience. We often take it for granted when we just hear the piece performed with nothing else. People will have a much deeper appreciation of the work when they hear it.

“1001 Arabian Nights†has its roots in the folklore of Persia and India, which scholars believe formed the early versions of the work. “Nights†was first published in the early 1700s, and it is believed by this time, having been translated into Arabic, many Arabic stories were added to the original list. These all culminated in the work we know today, which has influenced art, film, and of course, music. The most famous translation of the massive work was completed by Britain’s renowned Renaissance Man of the 19th century, Sir Richard Francis Burton.

UM: It seems LexPhil has really branched out in the last five years or so. I know the question is always there, but more recently it’s really been put to the Lexington community about the value of the arts in our lives. What’s your take on that?

ST: The arts are as important as they ever were. The various arts entities in this area work with each other to bring things to life. What is often the case in the arts is: “what do they bring to the economy of Lexington?â€

UM: There’s always the issue of money.

ST: Yes. And it is simply not enough to walk on stage and leave. There has to be advocacy through education, outreach, etc. One sees a lot of fear when the arts are threatened, but also a lot of people have been standing up and saying we must have them. People know inherently that the arts are integral to who we are, what we do, where we come from.

UM: No matter how much one may deny that fact, it will always be there, won’t it?

ST: There has to be a lot work beyond our individual realms. It gets people reinvigorated, reinitiated to life.

For times and ticket information, visit LexPhil.org.