Where do you think hip-hop came from? As a fan of the music, I’ve always been fascinated about how it all started and how one of America’s biggest genres of music came to be. Scholars cite New York City as the birthplace of hip-hop and the looping of the “breaks” of funk, soul, and disco records at DJ Kool Herc’s 1973 Bronx block parties as the genesis of the movement. At these parties there were two other critical members of hip-hop’s holy trinity, Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa, who went on, along with Kool Herc, to build hip-hop out of a small rec room of 100 people in the Bronx and spawn a world-wide cultural phenomenon.

However, I couldn’t help but wonder what inspired Kool Herc, Flash, and Bambaataa? Their ideas had to come from somewhere. Would we even have hip-hop if there were no James Brown or Sly Stone records for Flash to cut up or if Kool Herc’s Jamaican roots and experience with Jamaican sound system culture hadn’t shaped those parties? As I researched what events and interactions propelled these three artists, I was surprised to find that the group Yellow Magic Orchestra played a critical role in influencing Afrika Bambaataa throughout hip-hop’s early evolution. I wanted to know more, so with the help of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and interpreter Junko Takahashi, I traveled to Japan to find out. I explored the origins and branches of influence as I attempted to answer the question, “Did Japan invent hip-hop?â€

From as early on as the Heian Period (794-1185 CE), Japan has gained an international reputation for aggressively exploring existing concepts and technologies from abroad and making them uniquely their own, often improving effectiveness and quality beyond the original. This culturally adaptive interchange often results in a reciprocal exchange of indigenously Japanese ideas with the rest of the globe, leading to an impressively vast global impact for such a small island nation. Thanks to the pivotal connection between New York and Tokyo, the early history of hip-hop is no exception to this phenomenon, but where exactly does Japan’s impact begin?

The Digital Effect in an Analog World

It all started back in 1970 with Sly Stone and his Maestro Rhythm King MRK-2 drum machine. In 1971, Sly and The Family Stone released There’s a Riot Goin’ On, which reached number one on the Billboard Soul Album and Pop Album charts, almost immediately upon its release. This album was mostly recorded by Sly himself, at his Bel Air home studio, in the shadow of tense internal band conflict, pressure from Epic Records (and the Black Panthers) to put out new material, as well as a blissful haze of heavy drug use.

During these recording sessions, Sly and The Family Stone’s drummer, Greg Errico, was the first member to leave the band due to the internal conflicts, which left Sly with a missing rhythm section. Errico left and was replaced by session drummer Gerry Gibson to record a few live drum parts; however, Sly decided to mostly go a different route and utilized the Maestro Rhythm King MRK-2 drum machine for most of the album.

The MRK-2 has 18 pre-programmed rhythms, volume and speed knobs, and cannot be programmed, so with these limits on variation, Sly Stone manually overdubbed the beats to remove the artificial nature of the pre-programmed sounds. This change in personnel was the first time that a drum machine was front and center in a major album’s rhythm section because, until that point, drum machines were simply used as a complex metronome.

Following the success of 1971, Sly and The Family Stone went back to the studio and in 1973 came out with Fresh, an album noticeably softer than There’s a Riot Goin’ On, but still an honest reflection of the struggles of the moment. The album’s opening track, In Time, with its jerky polyrhythmic drum pattern went on to inspire a multitude of artists around the world to experiment with drum machines in their music, including a young Japanese musician named Haruomi Hosono.

Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO)

“In 1973, Sly Stone was already playing ‘In Time’ with a rhythm box and it was the biggest influence on me.†– Haruomi Hosono

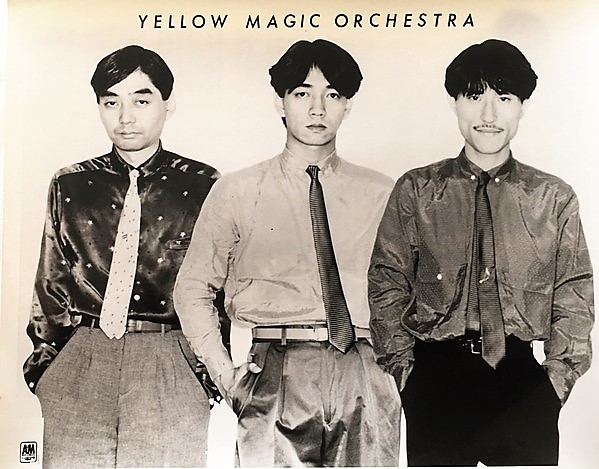

Hosono created the technopop group Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO) in 1978, which fundamentally invented J-Pop and techno music. YMO was one of the first (if not the first) to normalize mixing analog instruments with drum machines, samplers, and live programmers into their live performances. This new innovation took them to the top of the charts in Japan and changed the world of music forever.

The musicians in Yellow Magic Orchestra used sarcasm to make a mockery of the West’s naïve and offensive exoticism of Japan. All notions of the use of “yellow†were very purposeful, to take the power away from misconceptions about Asianness and subvert the stereotypes and expectations by letting international audiences know that they were in on the joke. Before the group was founded, all three members were established musicians in their own right.

Haruomi Hosono also played bass with the legendary Japanese 70’s folk-country outfit Happy End, which enjoyed some domestic success but disbanded around 1974. Drummer Yukihiro Takahashi was the drummer for glam-rockers Sadistic Mika Band (a name poking fun at Plastic Ono Band), which enjoyed a bit of international success including a tour with Roxy Music and a TV performance on the UK’s Old Grey Whistle Test program in 1975, before teetering out around 1977. Pianist Ryuichi Sakamoto was recruited to join Hosono’s touring band in 1976 and was working with the other “City Pop†musicians in Hosono’s network as a session artist in 1977 when the trio decided to form Yellow Magic Orchestra.

“I was always looking for new equipment and technology. It was not like now when various kinds of equipment are inexpensive and available. Around the time of the Sadistic Mika Band, the ARP Odyssey monophonic synthesizer was finally available. I was surprised at the performance of Sly and The Family Stone’s early Keio Donkama (Donca Matic) drum machine and I got one. I still have it and it’s wonderful.†– Yukihiro Takahashi

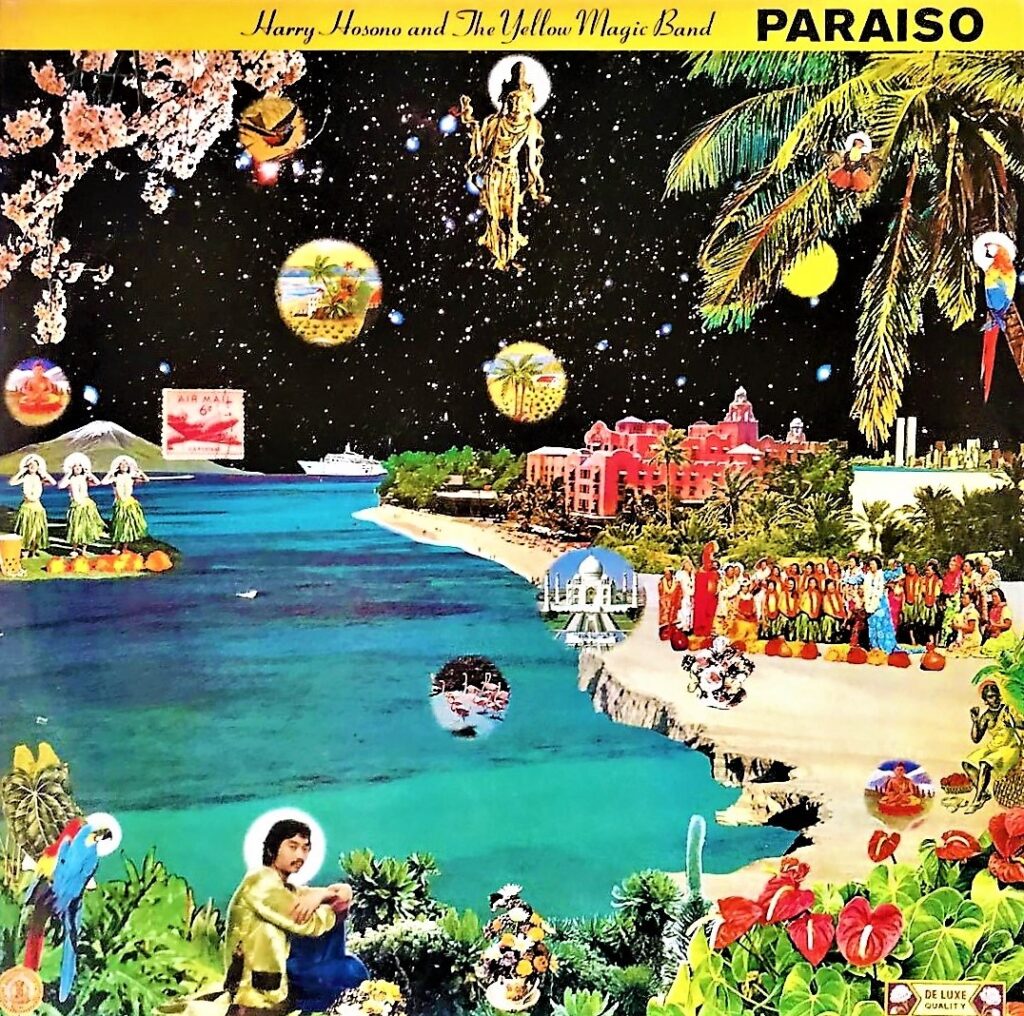

YMO started in Tokyo as a one-time project with a group of studio musician friends; however, the group would go on to unexpectedly top the charts in Japan and change the state of electronic and hip-hop music forever. The three first worked together in 1977 when Hosono invited Takahashi and Sakamoto to work on the track “Femme Fatale†on Hosono’s solo record, Paraiso, which utilized modern electronic equipment such as the Yamaha CS-80 and ARP Odyssey synthesizers. They called the band Harry Hosono and The Yellow Magic Band.

Sakamoto and Hosono had both been experimenting with different synthesizers and drum machines throughout the seventies and, on Sakamoto’s 1978 solo album The Thousand Knives of Ryuichi Sakamoto, Hosono was invited to join the sessions and used a very early version of the Roland MC-8 Sequencer on the track “1000 Knivesâ€. It was during these sessions that Hosono began to envision the YMO project.

In November 1978, YMO’s self-titled debut album was released in Japan on Alfa Records and was later picked up for distribution by A&M Records and released in the U.S. in May 1979. The recording sessions consisted of a hodgepodge of modern electronic musical instruments including the programmable Roland MC-8 Micro Composer and various other vocoders, electronic drum kits, and synthesizers. The only acoustic instruments included in the sessions were a marimba, a Steinway grand piano, and an acoustic drum set.

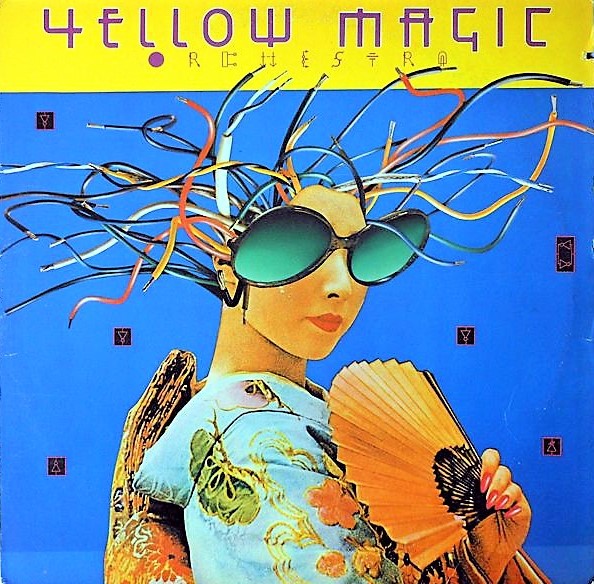

The album’s breakout single was a cover of 1959’s “Firecracker†by Martin Denny, which represented the epitome of the West’s superficial concept of “Orientalismâ€. The track was redone using synthesizer patches instead of traditional Japanese instruments. “Firecracker†and “Tighten Up†immediately became huge hits in Japan while gaining Top 20 R&B hit status in the U.S., and the song “Computer Games†became a top 20 hit in the United Kingdom. These songs went on to be sampled by everybody from De La Soul and 2 Live Crew to Jennifer Lopez and Mariah Carey. It is also worth noting that this album predated German electronic music pioneers Kraftwerk’s 1981 classic Computer World by three years.

In December 1980, YMO was invited to perform two songs on the popular American TV show Soul Train, hosted by Don Cornelius. The crowd responded well to this new style of music. YMO placed their manager Yoichi Ito in the midst of the Soul Train crowd on the floor, decked out in stereotypical Japanese square tourist garb and camera. His act was to be humorous, but when the group sang the line from Tighten Up, “Japanese gentlemen, stand up, please!â€, he danced exuberantly, and the Soul Train crowd loved it.

After the performance, Don Cornelius interviewed YMO. Takahashi explains, “MC Don Cornelius was a dignified person. I had a hard time with his ironic English question for me though. Soul Train was a popular program in Japan as well at the time and we were asked to play because ‘Firecracker’ was a big hit in discos. I remember that it was a unique studio atmosphere compared with TV programs in Europe that we appeared on. I was impressed that the cameramen and the staff inside the studio were all so true to their name Soul Train. Among the members of YMO, the influence of soul music is naturally strong.â€

YMO was the first and only Japanese band to ever hit the Soul Train stage. Hosono reflected, “I had an impression that there was not so much Techno music in America at that time, compared to England. Even so, YMO was on the R&B Chart with Firecracker, so that might have been why we were considered a soul band rather than a techno band. I think that is why we could be on Soul Train without any problem. Moreover, I believe they were curious about us as a ‘rare guest’ because we played ‘Tighten Up’, you know.†Takahashi added, “Many artists and bands came to see the live show in the US and visited the dressing room including friends and acquaintances in The Police, The Tubes, The Cars, Devo, etc. I cannot remember them all. John Sebastian was an enthusiastic fan of Hosono-san and a lot of artists belonging to A&M records, the same as us at the time, came. I assume that since we also did a concert for satellite broadcasting to Japan, probably there were many people who were invited and gathered.â€

YMO went on to play shows in New York at Hurrah and The Bottom Line in 1979 before heading to London, Paris, Hamburg, Rome, and numerous other venues around the globe, ultimately ending back in New York in the winter of 1980 to play a show at The Palladium. The Tokyo/New York musical relationship was strengthening and YMO’s sway on New York was merely at the onset.

Bambaataa

In New York City in 1979, a 23-year-old from the Bronx named Afrika Bambaataa was watching YMO on Soul Train. He reflected, “It was great to see them on Soul Train doing ‘Firecracker’ and ‘Tighten Up’ and for Don, the host, being wise and open to having them on the show as he did to so many other types of groups to come and give up their Funk on Soul Train. Great to see the crowd rocking to YMO, same as my Hip-Hop audience rocked to their music at my events a year earlier.â€

Bambaataa had started throwing block parties around the Bronx in 1977 and, along with DJ Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash, brought their new hip-hop movement to Manhattan, where it mixed with Greenwich Village bohemia. At that time, there was no distinction between disco, funk, or rap.

I asked Bambaataa how he learned about YMO in an era with no internet; he explained, “I had never heard of Yellow Magic Orchestra, and I was digging in record bins in one of my favorite record stores in the Village area of New York City in 1979 and I liked the cover of the album. Being one who always reads everything on albums, I saw the track ‘Computer Game’/‘Fire Cracker’. At that time, you couldn’t go and play a record in-store to see if you liked it, so I took a chance, bought it, took it home, and started going through the tracks. Right away, ‘Computer Game’/‘Fire Cracker’ I knew right off were going to be the songs I start pushing to my audience. I liked other songs on the album like ‘Tong Po’ and ‘Cosmic Surfin’ but knew ‘Firecracker’ was the serious Funk jam to play on my audience, who were always looking for me to come out with crazy music that will make them dance. This made me become a fan of their music myself and then, when I received the 12-inch version from the record pool, with a bigger and harder sound, this song became one of the early anthems of breakbeat music. I pushed these tracks for many years, which still stand the test of time today. Super big ups to Yellow Magic Orchestra, later known as YMO.â€

In 1983, Bambaataa included YMO’s “Computer Gameâ€/“Fire Cracker†into his legendary Death Mix 2, a vibrant live mix of records from all across the globe and representative of the energy present in the local early hip-hop scene of New York. Bambaataa is often heralded as the man who invented hip-hop, or at least took it out of New York block parties and shared it with the world at large. This title is often directly attributed to his revolutionary genre-bending electro-dance track that is “Planet Rockâ€.

Bambaataa was performing and record digging across New York City when, one day, Bambaataa and producer Arthur Baker were in the studio discussing their love of Kraftwerk. Baker had recently been approached by Tommy Silverman of Tommy Boy Records about producing a record for Bambaataa and they put out a track called “Jazzy Sensation†that garnered quite a bit of play. To follow up on that release, the duo created “Planet Rockâ€, which utilized the rhythm track of Kraftwerk’s “Numbersâ€, which Baker had seen people dancing to at Brooklyn’s Music Factory, and enlisted synthesizer player John Robie to play the rhythm live on the recording via a Fairlight CMI digital synthesizer. Bambaataa recalls, “There is nothing sampled on ‘Planet Rock’ whatsoever. Everything is played live and shows the mastery of keyboardist John Robie’s skills in playing them keyboards, which he sounded like Kraftwerk playing.â€

Another instrumental piece of the puzzle, which defined the sound of “Planet Rock†as well as more hit records than any other drum machine in history, was the Roland TR-808. In 1980, the TR-808 was originally released to provide backing rhythms for demo production and was capable of producing 16 different sounds using variable analog circuitry rather than the rigidity of samplers. When Baker and Bambaataa were putting “Planet Rock†together, they heard a TR-808 on another track and decided that they needed those sounds. Rather than buying one, due to their limited recording budget, they found “a man named Joeâ€, who had put an ad out in The Village Voice offering to rent out his TR-808 services for $30 an hour. Bambaataa added, “I love beatboxes, drum machines, synthesizers, percussion, and natural sounds and am always looking for whatever will keep my music funky, to dance, to think, and to make one to get up and dance or get involved socially, politically or Earthly. With the TR-808 sound, it became our Electro Funk Sound.â€

Bambaataa continues, “I first heard of Roland drum machines from a place in Manhattan that sold musical instruments and drum machines. I bought an earlier version and it became part of my DJ show back in the early days of building Hip-Hop Culture. I knew of the sound of drum machines by listening to Dick Hyman, with his Moog sound, and Sly and The Family Stone, from his There’s A Riot Goin’ On, a fantastic powerful album, and from his other group, Little Sister’s song called ‘Stanga’ and ‘Somebody’s Watching You.’ I heard and started messing with the TR-808 from experimenting for Tom Silverman, President of Tommy Boy Records, to come up with a new song for Tommy Boy, but it was the wizardry of seeing keyboardist John Robie and producer Arthur Baker in programming and working that TR-808 that I knew we were about to have something here that was going to be fire and that fire was ‘Planet Rock’. I always thank Sly and The Family Stone, Dick Hyman, Yellow Magic Orchestra, Graham Central Station with their Funk Box, and the mighty Kraftwerk for all making me aware of the beatbox sound and the wizardry of John Robie and Arthur Baker for funkin’ it up with all our influences to make up ‘Planet Rock’.â€

With all the parts assembled including Bambaataa, Robie, the lyrics of Soul Sonic Force, a guy named Joe and his TR-808, and Baker’s suggestion that they also add the melody from Kraftwerk’s “Trans-Europe Expressâ€, this unusual concoction laid the foundation for what would become Miami Bass and Detroit Techno as well as take hip-hop from local Bronx block parties to a global phenomenon.

“Do You Think You Can Rap?†YMO, BGM, and the Emergence of the TR-808

“Planet Rock†was released in April 1982 and, within five months, peaked on Billboard’s Hot 100 at #42 and spent eleven weeks on the chart. The song put Tommy Boy Records on the map and brought the multifacetedness of the TR-808, hip-hop, and Afrika Bambaataa into the global mainstream. Bambaataa became a star and traveled to Japan in 1985 to perform, inspiring a whole new generation of up-and-coming artists. Hosono ruminates on this time, “Bambaataa was a huge hit in that his songs were on the radio. I was very interested in his sounds because our favorite rhythm machine, the TR-808, was being used. Furthermore, his sampling style was different from ours, so we were influenced in that way too. I believe YMO was more accepted by fans of R&B and Hip-Hop rather than Techno. After that moment, we met up with Afrika Bambaataa.â€

YMO’s usage of the TR-808 preceded Bambaataa and the group used one of the first available units from Roland in their December 1980 live performances of “1000 Knivesâ€. Surprisingly, the TR-808 didn’t gain widespread popularity among musicians until years after its production ceased in 1983, so most machines used to create early hip-hop beats were purchased secondhand.

Following the fanfare of YMO’s second and most commercially successful studio album, Solid State Survivor, in 1979, the group enjoyed multiple #1 spots on the Japanese Oricon Singles Chart. Later that year, they released a live album and then headed back into the studio in January 1981 to start work on their new album, BGM. It was clear that their impact on the world of music was starting to sink in.

During this time, the group had rejected a request from Michael Jackson to release his cover of YMO’s track “Behind the Mask†on his upcoming Thriller album. While the song sat on the shelf for 28 years, a slew of other artists, in some strange cyclical realm of synchronicity, had already put out their own versions of Jackson’s cover. First, Michael Jackson had heard the YMO version of the song through Quincy Jones and recorded his own version with additional lyrics during the Thriller sessions in 1982. Jackson’s version of the song then made its way to Jackson’s keyboardist, Greg Philliganes, who released his own cover on his 1985 album Pulse. Then, Philliganes brought the track to Eric Clapton, who did his own cover, produced by Phil Collins, on his 1986 album August.

If that’s not weird enough, Sakamoto then went on to re-record the Jackson/Clapton version with Bernard Fowler handling vocals for a 1987 single, bringing the mutuality full circle. Yukihiro Takahashi lamented, “I had heard the cover at the time, and it is true that we refused. Ryuichi Sakamoto and I discussed it and we declined. However, I cannot remember the reason clearly. Anyway, we were both young. Thinking about it now, it is really a shame though….†In 2010, Epic Records finally released Michael Jackson’s cover of “Behind the Mask”, which had been previously unreleased, due mainly to a royalties dispute with YMO’s management.

BGM released in March 1981; it was YMO’s first album (and possibly the first of any album by anyone) to feature the TR-808 drum machine. The album’s production was mostly done by Hosono himself and their use of the 808 as an instrument, played with character and emotion rather than the industrial applications of Kraftwerk’s various drum machines, was groundbreaking. The album included a redone version of Sakamoto’s solo track, “1000 Knivesâ€, which utilized the TR-808 and mimicked the same layer that had been used for the live performances the year before. Sakamoto’s only new composition for the album, “Music Plansâ€, explored the possibilities of the 808 and you can hear the beginnings of that funky, electronic boom-bap vibe of hip-hop beats start to emerge.

BGM also contains a peculiar track called “Rap Phenomenon†(ラップç¾è±¡), which uses the TR-808 and feels like an aural Australopithecus of electronic rap music. As a corollary, famed Detroit hip-hop producer, J Dilla, went on to sample “Rap Phenomenon†on his track “Go Get Em†in 2013. I asked Hosono what inspired this track and how aware he was of the burgeoning hip-hop scene in New York, he told me, “’Rap Phenomena’ was a Japanese pun for psychic phenomena and rap. At that time, I had a sense of affinity more toward British music than American music. However, Toshi Nakanishi of Plastics, who came back from New York, showed me the latest information at the studio. That information was ‘scratch’. He showed me how to scratch records and tapes. After that, I was more interested in the American scene and started to listen to a variety of music like Grandmaster Flash and others. It was a significant event that scenes of scratch, hip-hop, and rap started to permeate techno, yet I believe it is not only YMO but also the recording style and programming that created the new era. I think intermingling all kinds of music that interact with each other can create interesting things.†Hosono would go on to try his own hand at scratching on his 1983 solo album SFX, on the track “Body Snatchersâ€.

“Except we all think and talk and sing so loud.

We don’t notice them.

We’re headed in the same direction,

Don’t you know? Neither down nor up.

We all talk too much. We all think too much.

Rap, rap, everybody rap.

Rap, rap, do you think you can rap?

Rap, rap, everybody rap.

Rap, rap, do you dig, I dig rap.â€

BGM was also a debut for their co-lyricist and new manager, renowned Tokyo DJ, festival planner, and music journalist Peter Barakan, who explained to me, “The guys in YMO were all pretty much aware of anything new happening in music, and that would have definitely included rap. Hip-Hop, as a genre, wasn’t really a thing yet, but rap was. It had been around since the seventies and probably earlier than that. I think we all had probably heard ‘Rappers Delight’ by Sugarhill Gang and then the early Grandmaster Flash records and those were really new and fresh and something that none of us had ever heard before. I would imagine that Hosono was influenced by that.â€

Regarding their use of modern technology, Barakan remarked, “From the very early days of YMO, there were numerous banks of boxes with dials and patch bays attached but synthesizers were becoming very sophisticated rather quickly. I think YMO had, pretty much, everything that was brand new, as it came out. The one that they were using an awful lot when I started working with them was the Prophet 5 from Sequential Circuits. That was a wonderful machine and Sakamoto made sounds on that synthesizer that I don’t think I’ve ever heard anybody do before, or since probably. He definitely had his very unique sound on that. From the time I started working with them, the sequencer they were using was the Roland TR-808 and, subsequently, the 404. Those were used in the studio daily. All of the rhythms were basically done with that.â€

Hosono clarifies that “The TR-808 is still my favorite machine. Since that sound is close to the Japanese Wadaiko drum, it has a unique presence. Roland was an innovative company that was making excellent products before [many] musicians were aware. When we noticed, it was already in the market as a product, and when I bought and used those products, many of them were great. For example, the MC-8, a microcomputer for music, was one of the most important machines (for me). As for sampling machines, the engineers of our group, Hideki Matsutake and others, made a prototype and we tried it at a studio. I was amazed with its potentiality. At the beginning, we could sample only for three seconds, but it was enough as a rhythm machine to control with MIDI. On BGM, we used a 32-Track digital recorder that 3M developed for the first time, and we did not like it because it had a particularly crisp sound. So, when we recorded the rhythm, we did it with a 4-track analog recorder produced by TEAC. It became the sound that I really liked.â€

Barakan specifically worked with YMO on the albums BGM, Technodelic, Service, and a couple of live albums. “I worked for the management office of Yellow Magic Orchestra from about halfway through their career, the very end of 1980 until the band broke up in 1983.†Before working for the group, he wasn’t so into their sound and “found their particular brand of technopop not very much to my taste.†However, when 1980’s X∞Multiplies (Zoshoku増殖) 10-inch mini-album came out, the mix of more approachable musicality and comedy skits turned Barakan into a fan. Shortly after that album came out, Barakan was asked by YMO’s management to work for them to place publishing rights of their songs with companies outside of Japan, which was the opposite of his previous work handling the distribution rights of foreign artists in Japan for a different major record label. “It was actually a lot more difficult than I had expected. Europe and the U.S. weren’t really ready for that kind of music yet.â€

He described the initial reception as fairly chilly. “The media, in particular, weren’t really ready for it. There were some musicians who were into it.†He added, “The label that YMO was on at the time, Alfa Records, was the Japanese distributor for A&M records, and the label coordinated for YMO to be the opening act on an American tour with A&M signees, San Francisco rock group The Tubes. Alfa sent over a whole group of Japanese journalists, who all came back to Japan, and wrote up their reviews of the concert saying YMO takes over the world basically; it was a real big hype job and it was very obviously so, in my eyes, which gave me kind of a jaundiced view of the group at the beginning and it took me a while to get over that.â€

Barakan mentioned that it was none other than prolific studio musician and producer Bill Laswell who had deepened his understanding of early hip-hop and introduced him to the world of his Celluloid Records label-mate Fab 5 Freddy. “I personally had been listening to Grandmaster Flash and a few things like that; not an awful lot of hip-hop. I remember, I can’t tell you exactly which year it was, I’d need to check some release dates and stuff, but Bill Laswell had started working with Herbie Hancock on ‘Rockit’. Maybe that’s ‘82? I remember Bill Laswell coming to the office and he brought with him a slew of 12-inch records, things mainly on Celluloid records, like Fab 5 Freddy. Anyway, he brought some records and played them in the office, and they were really cool. From his visit, I got to know more about the scene than I had before.â€

As an aside, Laswell’s group, Material, who released records on Celluloid, were also the first group to feature a young vocalist named Whitney Houston on their 1983’s album, One Down, which also features a cover of Sly and The Family Stone’s “Let Me Have It Allâ€, usage of the Roland TR-808, as well as contributions from Brian Eno and Archie Shepp.

The two worlds of YMO with Alfa Records and Afrika Bambaataa with Tommy Boy Records would overlap frequently in serendipitous ways and the interplay between the two would help form the skeletons of hip-hop and electronic music in both New York and Tokyo. Peter Barakan described a chance encounter between himself and Tom Silverman (Tommy Boy Records) at a French media conference, “I went to Midem, the music industry convention in January of 1982, and I was walking into the convention center and all of these different record companies and publishing companies have their little stands there and I noticed that Tommy Boy had a stand. I went up, because I was doing a radio show, to see if I could score some 12 inches to play on the show, and, it turned out that the guy at the stand was Tom Silverman himself. God knows, he was probably running the label by himself in those days. So, I asked him, “Do you have any Bambaataa albums?†He said, “Yeah, sure, here.†And he gave me a couple. My badge had my name and the country that I was from, and it said Japan and he asked me, “Oh, which company are you with?†So, I said, ‘Well, I’m a freelance DJ and I’m also working for the management of Yellow Magic Orchestra. ‘ And he said ‘Wow, Africa Bambaataa is a real fan of Yellow Magic Orchestra and he’s quite influenced by them.’ I thought ‘Wow!’ because, in those days, obviously in Japan they were big stars, but outside of Japan, hardly anybody knew about them. So, the fact that a groundbreaking hip-hop artist was influenced by them just blew my mind.â€

In a 2018 article in The Guardian, Ryuichi Sakamoto recalls Afrika Bambaataa telling him that “Kraftwerk and YMO made hip-hop.†According to Hosono, YMO met with Bambaataa a few times and he recalled one of his first encounters, “Hip-hop is their culture, and it is closely related to dance. Kraftwerk and YMO’s music was the music that gave a stimulus to them. Around 1984, when I went to New York, I asked Bambaataa to listen to one of my solo songs ‘Body Snatchers’. I went to his office and I remember that, after he listened to the song, he only said one word: ‘Crazy’. I thought he did not like it and I was a little disappointed.â€

Even though YMO broke up in 1984 to focus on their own voluminous solo careers, their footprint permeated exponentially throughout Japan and the world. The trio has occasionally gotten back together to perform and record new music from time to time. In 1993, they released a reunion album called Technodon. In 2007, the trio reunited for the Earth Hour worldwide festival campaign in Kyoto and, in 2011, went on to play a series of gigs around the world spanning from LA’s Hollywood Bowl to Japan’s Fuji Rock Festival.

In 2012, Sakamoto organized the No Nukes 2012 festival in Chiba, which had YMO performing on the same stage as Kraftwerk. Six years later, in 2018, Hosono played a concert at London’s Barbican Theatre where he was joined by the other members to perform “Absolute Ego Dance†together. This performance came about after U.S. record label Light in the Attic re-released five of Hosono’s solo records for the first time overseas.

The original three members united to perform songs and skits for a 2019 New Year’s NHK television special called Yellow Magic Show 2 with other Japanese musicians like Cornelius and Hoshino Gen, who were no doubt just a few of the many artists impressed heavily by YMO.

Hosono currently hosts a Sunday radio show on Tokyo’s InterFM called Daisy Holiday. He has recently been featured in a series of documentaries called No Smoking and Sayonara America that feature a look back on his 50+ year career as a musician.

Sakamoto continues to work as an Oscar-winning film composer and collaborate with artists across the globe on musical projects. The 2018 documentary about his life, Coda, showcases Sakamoto’s career, creative process, as well as his fight against oropharyngeal cancer.

Takahashi recently remastered his 1978 debut solo record Saravah! with new vocals and appearances by Sakamoto and Hosono and released it as Saravah, Saravah! in 2018. After being diagnosed with a brain tumor in 2020, he made a full recovery and continues to perform with his group METAFIVE, who released METAATEM, along with a live video performance, in November 2021.

Even in their solo modes, the half-century of direct and indirect outcomes of YMO on the world of music is in no way merely a thing of the past but is, in fact, very much alive in the present and will, undoubtedly, be present in the future. The results of this global exchange were and are currently being expressed vibrantly in the world of Japanese hip-hop.

Japanese Hip-Hop Takes On a Life of Its Own: DJ Krush, Crazy-A, and B-Boy Park

“Like techno, there are lots of interesting rap artists in Japan. Some songs surprise me sometimes. Rap seems suitable to the Japanese language unexpectedly, I mean, more (suitable) than French or Russian.†– Hosono

With the initial effect of YMO on Bambaataa, New York’s hip-hop future was forever altered, and this cyclical trajectory of hip-hop’s evolution quickly found its way back to Japan. In March 1983, a film about graffiti artists living in New York’s blossoming hip-hop scene called Wild Style premiered in New York. The film, despite being a fictional story, gave the world outside of NYC its first glance at the four elements of hip-hop (MCing, turntablism, break-dancing, and graffiti) as well as of hip-hop architects Fab 5 Freddy, Grandmaster Flash, Rock Steady Crew, and Bambaataa’s fellow Soulsonic Force and Zulu Nation member, Queen Lisa Lee.

The film did its first limited run in theaters around the U.S in November 1983, however, one month earlier, the film Wild Style found its way to Tokyo’s Shinjuku Ward and opened at the Milanoza Theatre. In Japan, the film was a huge success and, one year after the premiere, all 36 members of the artist and breaking crews from the film did a tour of Japan. The film was an education for the Japanese audience and the scenes depicting the four elements of early hip-hop fundamentally sparked the genesis of Japanese hip-hop.

In the crowd at Shinjuku’s Milanoza Theatre was a 21-year-old Ishi Hideaki, who would come to be known as DJ Krush. Considered by many to be the godfather of Japanese hip-hop, DJ Krush told me that, after watching Wild Style’s rappers, DJs, B-boys, and graffiti artists, he tried to learn hip-hop’s four elements from watching the film, but it wasn’t enough, and he had to figure things out on his own. When he went to a local instrument shop to buy two turntables and tried to explain the DJ setup by comparing a mixer in the middle to a bento box, the shop owner just couldn’t understand and yelled at him, “You don’t need two turntables!â€

A resident of Tokyo, DJ Krush’s father was a house painter and his mother owned a snack bar. When he was a junior high school student, he was already very interested in music and formed a band with his friends. At the time, he was listening to a lot of classic hard rock like Deep Purple and Led Zeppelin. When the crew from Wild Style did a promotional tour in Japan, DJ Krush saw them perform at Seibu Department store in Ikebukuro. They were break-dancing and rapping, and this was the first time that DJ Krush saw someone scratching records on two turntables with his own eyes. At the time in Japan, there were regular DJs, but no one had seen anything like that before and if DJs wanted to learn, they had to find the information themselves.

When I met up with Krush in Shibuya, his energy as a person seemed to match the vibe of his music: playful and relaxed, yet simultaneously serious and complex. As we sipped iced coffee and talked, he showed me a series of old photos that he had taken and meticulously organized in plastic baggies. Among this invaluable set of photos were moments when the Wild Style crew first came to Japan, Run DMC’s first Japan tour in 1986, as well as Krush’s first turntable setup, “the bento boxâ€. I asked if he had plans to publish any of these photos in a book. He laughed and said, “Maybe after I die.â€

I asked Krush for his thoughts on the early history of Japanese hip-hop. He told me that, at first, there was the 1983-era of Wild Style and people learning how to do everything on their own. Then, from the end of the eighties into the nineties, many DJs were performing and creating their own communities; they attended TV events and competitions that featured the Wild Style crew. Krush mentioned that, during this era, the hip-hop communities split. There were people on the street breaking to Bambaataa beats, like his Krush Posse crew from Harajuku’s HokoshaTengoku (Pedestrian Paradise) events, juxtaposed against more academic types, who wanted to understand the new musical phenomenon as subcultural anthropology. At Pedestrian Paradise, onlookers always thought this was a rare thing to see and lots of elderly people, who had never seen anything like it before, were constantly asking them what the hell they were doing.

“Just copying someone doesn’t work. Hip-hop was born in America, so we kind of borrowed it, and to return something that we borrowed as-is is not good. Some kind of personal flavor or character has to be added. This is the most important thing.â€- Krush

In 1986, while he and his friend Muro were performing on the street, New York artist Keith Haring visited Tokyo and started tagging alongside them. He gave Krush some words of encouragement and told him to keep going. Krush recently had a new child, so Haring signed a record as well as a “congrats on your baby†card, which Krush said he still has to this day. Again, the cycle of impressions between Tokyo and New York emerged. He told me that in Harajuku, after their event, the traffic would start moving again at 6:00 pm and one of Haring’s chalk pieces remained in the street. He said that the image of the cars dragging the brightly colored chalk in different directions was moving and will stay with him forever. I asked Krush if he tried his hand at graffiti, break-dancing, or rapping before focusing in on turntablism, and he said that he tried it all, but after recording a cassette of him rapping, he decided it was garbage and literally trashed it and didn’t save any copies.

Krush started out with B-Fresh, Japan’s first hip-hop group to record with a major label. He told me that some of the first records that he bought with his own money were Stevie Wonder and funk 45s that he still has today. After transitioning to DJing with the Krush Posse crew, he decided to go solo around 1992 and received an offer to do a remix for a film called TVO. Paul Bradshaw, founder of the London-based jazz magazine Straight No Chaser heard this acid-jazzy remix, and Krush’s demo tape, and did a write-up for the magazine. After this, Krush’s music spread throughout England and the rest of the world.

Krush is always pulling from different sources to get samples to build his soundscapes. “When it started, we were just following American hip-hop, looping funk songs, but now, when I want to draw my picture, it’s not enough; I need more colors, that is why I add nature and other instruments – I’m trying to make my music.â€

Krush put out his 11th studio album, TRICKSTER, in 2020 and has undeniably achieved the highest degree of international acclaim for a Japanese producer through his impressive number of EPs, singles, remixes, and collaborations with everyone from Bill Laswell to Black Thought, from The Roots to Mos Def, to k.d. lang and YMO’s Ryuichi Sakamoto.

I brought up Bambaataa’s quote from The Guardian that “YMO invented hip-hopâ€, and Krush gracefully explained that they had stimulated the beginnings but didn’t really invent it, and that this was his first time to consider YMO’s bearing on hip-hop. “At that time, the music of YMO was called ‘Techno’ and the BPM of Planet Rock was very fast, so this is convincing to me that they were influenced by YMO. In the mid-eighties, Hosono Haruomi was doing raps and, I think, very slightly, they had some contacts and I would be very happy if YMO was the root of all hip-hop!â€

When I asked Krush what he wished Americans knew about Japanese hip-hop, he replied, “I think in Japan we have a very unique culture, like anime and so on, so rap music is also about using the original things from Japan, so I want people to listen to that. And it’s not just rappers, but there are many good DJs and producers, and with the internet, you can listen wherever you are in the world. In the past, hip-hop was American-dominated but now it’s different. Actually, all the equipment, like Technics and Akai, is from Japanese companies, so we were feeling bitter that Americans were using Japanese equipment better than we were, but now it’s different. When I was first DJing and I felt like I wanted to show it to the people, I went to Harajuku and there were break-dancers and Keith Haring came and he told me to keep doing it, and so it made me believe in it, and that’s why I’m here right now. I feel indebted to hip-hop, which gave me so many important things. Now, I’m trying to give back to hip-hop the precious things that hip-hop gave to me.â€

While DJ Krush was impacted by the DJs in Wild Style, another Japanese hip-hop pioneer, Crazy-A, was being moved by another aspect of the film, specifically the break-dancing work of Rock Steady Crew. In that same year, 1983, Rock Steady Crew also performed a scene in the movie Flashdance and Crazy-A recalled that moment, “The Rock Steady Crew was dancing in the film and I was very shocked. That was my entrance to hip-hop.†Crazy-A, a native of Asakusa in eastern Tokyo, was a founding member of the Japan chapter of the Rock Steady Crew and went on to start B-Boy Park, a critical yearly event in Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park that went on to become a keystone in the evolution of Japanese hip-hop.

“After seeing the film in 1983, I started looking for dancing and, at the time, here in Harajuku, it was where all the young people got together and, here, they closed the street and made it only for pedestrians. There were rock and rollers and Takenoko-zoku [dancing] groups were here, so I thought, if I come here, there’ll be someone doing it, but there was no one doing it, so I started it myself.†The B-Boy Park movement was slow to start, but Crazy-A’s steadfastness to build a community of B-Boys proved beneficial. “I was kind of lazy to go look for other people dancing, so I thought, if I dance here every Sunday, people will come here. So that’s why I was dancing every Sunday. Every week we were here, so people who were interested in hip-hop were sure to come at least once. At first, people came here to get information because there was no other information anywhere, but afterward, I formed this group, Tokyo B-Boys, so everyone would come here and, for those confident in their technique, would have dance battles.†One of those people who came to get more information and then went on to perform with the group B-Fresh was DJ Krush.

From watching Wild Style, Crazy-A and his brother had learned about the four elements of hip-hop and began exploring them all before breaking. “Even before I started breaking, I had already obtained turntables and there was not a mixer being sold in shops, so I made it myself. There is a place called Akihabara and they sell radio parts and faders, and, since I was little, I was going there, so I bought all the parts and I bought two radio cassette pieces and took the monitor from there and made the mixer myself. I did everything.â€

“I was doing the same thing in Tokyo that those boys were doing in the Bronx at that time.â€

Ultimately, breaking is what most interested Crazy-A, and so the Tokyo B-Boys would set the foundation for Japan’s hip-hop community to gather when international hip-hop artists would visit when traveling through. “After we entered the nineties, I got to know Crazy Legs after he won the DMC Championship in London with Mix Master Mike and another Rock Steady Crew DJ. They were coming to Japan for the tour and, for the first time, I met them and had a chance to talk to them. I told him that I saw the movie and that we had been doing this in Japan and we became friends. Crazy Legs would later ask Tokyo B-Boys to join their network of breaking groups around the world and that’s how Rock Steady Crew Japan was born.â€

“At that time, break-dancing was falling out of style and New Jack Swing, like MC Hammer and Bobby Brown, was the new fashion that came. I was talking with Crazy Legs about this, and I think he was also feeling the danger of break-dancing disappearing and saying that real hip-hop includes breaking, so we have to continue, so I kept dancing. Around 1996, Harajuku’s Pedestrian Paradise had stopped, and I decided that maybe we should rent this place and celebrate our Tokyo B-Boys anniversary twice a year.â€

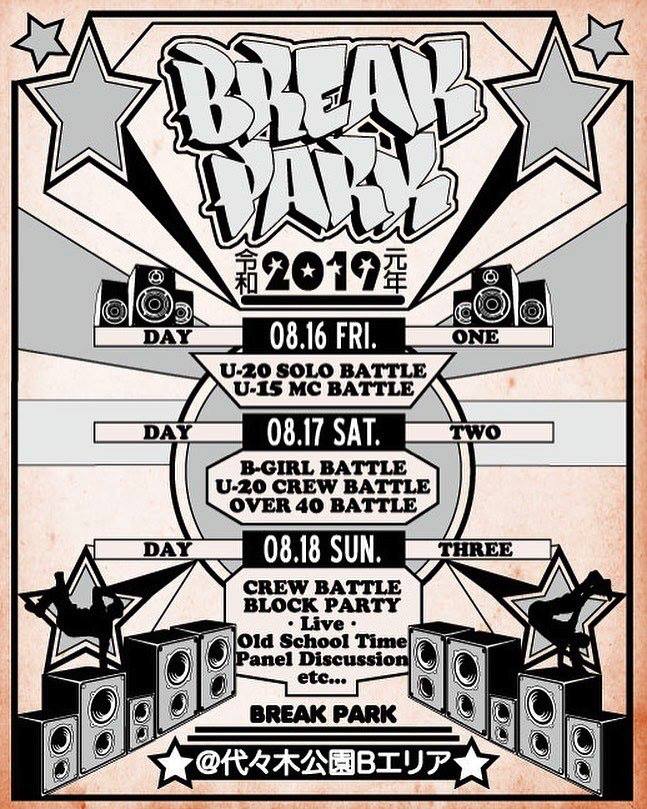

The event B-Boy Park started in 1997 as a free celebration of the 15th anniversary of the first Tokyo B-Boys gathering in 1983. The location of the event was the Yoyogi Park outdoor stage and included a collection of DJs, MCs, and B-Boys. 1998 was when they decided to call the event B-Boy Park and 1999 was when the MC battle element was first added. Over the next 20 years, the event would go on to expand to multiple days and venues, adding DJ battles and graffiti exhibitions, and hosting international hip-hop artists as judges, such as Crazy Legs from Rock Steady Crew in 2001 and Afrika Bambaataa in 2004.

In 2017, B-Boy Park came to an end because, as Crazy-A told me as we stood in front of the stage where it all began, “We did it for 20 years and, last year, we ended at once, because there is a rule that the B-Boy has to retire after being a B-Boy for 20 years.†This burgeoning era of Japanese hip-hop is best summarized by writer Ian Condry in his book, Hip-Hop Japan, “In the late nineties, Japanese hip-hop became more commercialized, but that commercialization developed alongside a widening and diversifying underground scene, encompassing artists and fans from a broader range of socio-economic backgrounds and from throughout Japan, from Hokkaido in the north to Okinawa in the south…. B-Boy Park 2001 demonstrated that there exists no singular Japanese approach to hip-hop, but rather a wide range of artists competing to promote diverse visions of what hip-hop in a Japanese setting might be.â€

I pressed Crazy-A to tell me what’s next for the B-Boy Park movement, and he told me his plans: “When I started B-Boy Park, it was right when my daughter was born and break-dancing was losing popularity, so I had a feeling that I wanted to rear my child but also the break-dancing scene. In Japan, adults were always dancing, but I was thinking that people should start as early as possible, otherwise they cannot compete in the world. I started break-dancing when I was 20 years old, and the information was not there at that time. The ages of dancers at B-Boy Park were getting younger and younger and, in the last few years, the winners were 17-year-old and 18-year-old boys. Originally, breaking was kids’ culture, so now in Japan, we have brought real hip-hop back to the kids.â€

Crazy-A organized an event in lieu of B-Boy Park for kids younger than middle school because “showing real hip-hop to the future is the only way to keep it alive.†The program would have students graduating at 20 because, as he said, “If you start later than that, it’s already too late.†In August 2019, this concept formed into a three-day event called “Break Park†at the same Yoyogi Park stage.

Is there a uniquely Japanese style of break-dancing? Crazy-A answered, “I think Japanese are more sensitive and more particular about small things and the details. When I went to New York, I had already quit dancing, but I don’t think there was anyone better than us. Still, now, Japan is the strongest, I think. It could be an exaggeration, but still I can say that we are quite strong…especially girls. I don’t know how many times they have consecutively won the world championship. Also, for the Youth Olympic Games, Japan was the winner for both the boys’ and girls’ break-dancing.â€

It’s true that Japan is consistently dominant in world B-Boy and B-Girl competitions and that hip-hop dance has broken into the mainstream with numerous television shows aimed at showcasing the strongest. Japanese youth are also dominating the world of DJing and, from those days of bento box mixers, has quickly evolved. In 2017, DJ Rena from Nara became the youngest person to ever win the DMC World DJ Final at the age of 12 years old.

I asked Crazy-A about how he has seen Japanese hip-hop change over the last 35 years. “I don’t think it’s changed, but in the beginning, we, Tokyo B-Boys, were doing everything in hip-hop culture. At that time, the highlight was the breaking, so that’s why we were working very hard on the dances. Eventually, the rappers, and DJs, and other elements split off, but I don’t say that only doing one of the other elements cannot be hip-hop.â€

Bambaataa and Zulu Nation’s four pillars or elements of hip-hop are breaking, DJing, graffiti, and MCing, and these concurrently developed in Japan at the same time that they were in New York. The first club only for hip-hop, called “Hip Hopâ€, opened in Shibuya in 1986 and was fertile ground for multiple pioneering Japanese hip-hop artists such as DJ Yutaka, who is now a member of Bambaataa’s Zulu Nation. Since the mid-90s, Club Harlem in Shibuya has been the mecca of live hip-hop in Tokyo. On the radio, no one supports the Japanese hip-hop community more than WREP, founded by Japanese rapper Zeebra, who also opened up a bar next to the radio station to feature local DJs and rappers.

As far as access to the records themselves, there are now lots of record stores across Japan selling hip-hop but none more critical to the nationwide community than Shibuya’s Manhattan Records.

The shop originally started behind the Shibuya police station selling second-hand soul records and moved in 1992 to its current location in the backstreets of Shibuya. Since its inception, Manhattan Records has been the largest hub for distribution of all things Japanese and Western hip-hop and has been supporting independent Japanese artists, in and outside of Tokyo, for more than 30 years.

Masatoshi Kiyokawa, manager of Manhattan Records, explains, “I believe that there are not many shops exclusively dealing with hip-hop, not only in Japan but also in the world, so we want to convince the people.†Most of the employees of the shop moved to Tokyo because they love hip-hop and bring an awareness of local artists and scenes to their hometown regions. Masatoshi personally got into hip-hop in high school, but as a junior high school student listening to Kick the Can Crew, he initially thought that hip-hop was a subgenre of pop music. After discovering sampling and artists like Pharcyde and Jay-Z, he learned more about Bambaataa’s four elements of hip-hop and thought it was cool. “If Japanese rappers rap in English, they’re just copying it. It was very significant to rap in Japanese. Hip-hop came to Japan from America, it was digested, and then artists made Japanese hip-hop music.â€

“The hip-hop that was born in Japan, like Nujabes or DJ Krush, those great producers are getting popular in America, and I believe it’s because that music has good parts of Japan included, with Japanese emotion or sensibilities of Japanese people. I think the people abroad are impressed in the same way. Not only hip-hop, but I also want lyrics to spread the same as hip-hop. In Japanese language hip-hop, the artists have really cool lyrics and I hope they are transmitted to the world. If they can express themselves in English, that would be great, but if it’s just simply translated, it could have a different meaning or interpretation. Someone who can transmit, in English, the Japanese particular language, that will be interesting, and more different people will listen to Japanese music.â€

Who invented hip-hop: Japan or New York? At what point within the exchange of Sly Stone’s drum machine influencing YMO, which resulted in Bambaataa’s Planet Rock, which impacted Rock Steady Crew (who became members of Bambaataa’s Zulu Nation), who reverberated with DJ Krush and Crazy-A, can we really say hip-hop started? For some final closure, I asked Bambaataa, the Godfather of Hip-Hop, for his thoughts.

“First, I am very aware of the influences of many groups and there was music before Sly and The Family Stone, then there was the music that Sly and The Family Stone changed. Everyone wanted to give up the Funk after Sly and The Family Stone and James Brown, The King of Soul, not The Godfather of Soul, ‘cause James Brown was way bigger than being called The Godfather of Soul. Sly Stone’s mind in music, lyrics, singing, and sound was no joke, and the same with YMO for Japan and, no, YMO did not invent hip-hop, as of here in the states, but definitely gave a strong push for their Techno Pop to bring in me along with Sly, James Brown, George Clinton, and Kraftwerk, for me to bring that Electro Funk Sound. Thank the Great Supreme Force, the Great Spirit for giving us all the will and Ideals to learn from each other, to respect each other, and to produce wonderful music for Humans and even Extraterrestrials, and music for Subterranean World Beings, to like on Earth.

In our Earth and our Universe,

Ã…mÄ—n.â€

Afrika Bambaataa asked me to share his list of favorite YMO Songs, available on popular streaming music services (YouTube, Spotify, etc.):

| Computer Games/Fire Cracker | Tong Poo | Simoon |

| Cosmic Surfin’ | Tighten Up (Funky) | Cue |

| Music Plans | You Got to Help Yourself | Technopolis |

| Sports Men | Behind The Mask | Perspective (great piano intro. AB) |

| Ballet | Nice Age | Riot in Lagos |

| Close to You (Hosono’s Remake. AB) | The End of Asia | Gradated Grey |

Check out Chuck Clenney’s epic 2018 series “20 Female Japanese MCs Changing the World of Hip-Hop”. The series can be found in our Collections menu.