The Lexington Philharmonic Orchestra is about halfway through their 2017-2018 season, and the halfway point for the Lexington Philharmonic is unique.

Like any classical orchestra, each concert has an entirely different repertoire, and classical music is notoriously technically difficult to play, even for professionals. It’s all the more remarkable, then, that Maestro Scott Terrell assembled a concert that had the most adventurous and audacious program yet presented this season. It’s a testament to the skill and artistry of the Philharmonic that the concert was a jubilant experience.

The first piece of the evening at the University of Kentucky’s Singletary Center for the Arts was a standard in the repertoire of any orchestra: Giacomo Rossini’s Overture to The Barber of Seville. As Daniel Chetel notes in his program notes for the Philharmonic, this piece is likely familiar to anyone, classical aficionado or no, as the score to the Looney Tunes’ “Rabbit of Seville†cartoon.

Rossini wrote in the full Italian style, emphasizing easily singable (or hum-able) melodies that work their way into the ear and stay there. The key to a good performance of Rossini, then, is to make the sound as clear and clean as possible. This was no challenge to Terrell and the Philharmonic, who obviously enjoy playing the piece.

It’s still a remarkable sight, no matter how many orchestral performances you see, to watch nearly twenty violinists move their bows in absolute unison. It’s a mix of technical precision and passionate artistry that’s quite peculiar to orchestra concerts.

That doesn’t mean that there’s no cutting loose, though. At one point towards the end of the overture, Terrell turned to the side of the podium facing the violist and—and I really can only use this word—boogied with him, while still marking time for the rest of the orchestra.

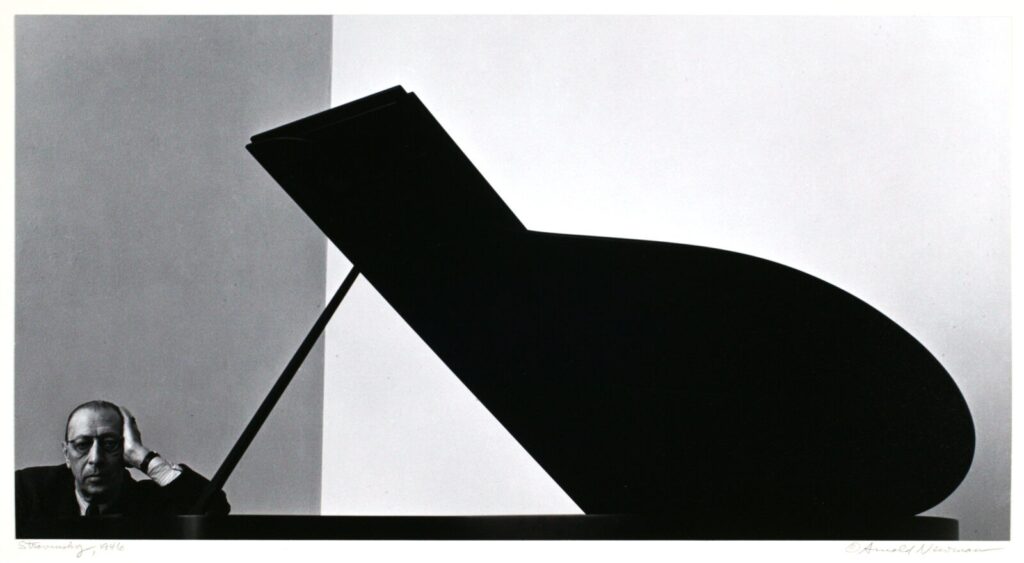

The main piece for the first half of the evening was a suite of music drawn from Igor Stravinsky’s 1920 ballet Pulcinella. Stravinsky, unquestionably the foremost composer of the 20th Century and possibly the greatest single composer since Beethoven, wrote this piece in the early part of his neo-classical period. After an early career in the 1910’s redefining the sound of not just ballet but the entirety of classical music with pieces like Le Sacre du Printemps and Petrushka, Stravinsky spent much of the next few decades attempting to turn back the musical clock. His neo-classical style looked back to the Baroque period, with delicate counterpoint and strict dance forms, as a basis for containing the seemingly infinite musical options available to the composer.

Even within the supposedly restrictive forms used in the suite, Stravinsky created a sound world all his own. He spins from one musical idea to the next, never settling on one path for too long, but circling back to explore all the options available. Through just one moment of the suite, the orchestra goes from a delicate but cheery violin solo (performed both passionately and expertly by concertmaster Daniel Mason) to a booming thundering clamor from the bass instruments, and then right into a lush orchestral swell under a resumed violin solo; this all happens within perhaps fifteen or twenty seconds of music.

It takes a titanic effort simply to keep everyone together during those moments, and it’s obvious that not just Terrell but the entire orchestra are listening intently to each other.

Stravinsky’s music is always its own sound world— the melodies always sound half familiar, but still distinctly unlike anything that you would think of humming to yourself as you wash the dishes. Towards the end the trombonist and a bassist juggled a short set of phrases back and forth between them, only fully joining into one voice as the whole beast roared into a fanfare for the finale, creating an effect that is both predictable and surprising all at once.

There are plenty of traps for players in Stravinsky’s music— sudden stops for the stings, an out-of-nowhere flute solo that has to soar above the whole rest of the sound and glide gracefully back down— and lesser orchestras often trip up on these moments. Not the Philharmonic. When the violins drop out, they drop out as one, and when they return, it’s as though each bow is connected to the same hand.

The neoclassical style can sometimes sound simplistic or reductive, but Stravinsky orchestrates in an extravagant manner, and the Philharmonic was able to accentuate each part of the whole in such a way that the listener could observe not only the entire effect but the way that every component contributed to the entire experience.

After an intermission, the Philharmonic returned with Vaughan Williams‘Â Overture to The Wasps.

Williams wrote a whole set of music to play with a production of Aristophanes’ ancient play, but the overture has found a second life among orchestras. It’s obvious why the Philharmonic was attracted to the piece—it has a style that overflows the bounds of the hall, filling the air with thick and overwhelmingly pleasant harmonies.

Williams’ overture runs about nine minutes, and it’s an excellent example of what classical composers can do within that time frame. Whereas pop music tends to be shorter in length and quite focused in terms of form and aesthetic, classical composers often feel free to roam about and wander through their material. Williams offers an example of this—there are no moments of quick change or unexpected leaps to new sections, only a continuous unfolding of transition upon transition. In the capable hands of Terrell, the music flows in an almost out-of-time manner.

The main event of the evening, however, was last.

In his time at the Philharmonic, Terrell has been a champion of new music. In his comments to the audience before the last piece, he said that he believed that orchestras have an obligation to present the “voices of today†to audiences. To accomplish that, the Lexington Philharmonic commissioned a new concerto from renowned composer Chris Brubeck, to be played by the world-famous Canadian Brass.

The concerto, entitled No Borders, was an unequivocal triumph for both composer and orchestra. Brubeck has a style that’s reminiscent of Leonard Bernstein, with lots of irregular meters that shout this is genuine American music, and a relentless and optimistic rhythmic drive that throws the piece constantly forward. The Canadian Brass played not just spectacularly, but in magnificent combination with the orchestra—totally in sync, and the whole feeling was one of camaraderie and unity of purpose.

Brubeck’s jazz-influenced style moves effortlessly between a kind of joyous wailing and winging about and moments of passionate harmony that seem suspended in time. He comes by that influence honestly as the son of the great jazz pianist and composer Dave Brubeck. As the piece moved from a rollicking opening movement that brought to mind West Side Story and big band standards to a suave slow second movement, Canadian Brass and the orchestra, with seemingly no effort, demonstrated a graceful and subtle exchange between instruments that’s a hallmark of the highest level of playing in both jazz and classical music.

The final movement was like a tour of the Alps, moving from one glorious peak to another. With a rhythmic swing that bounces the head up and down and rolls the sound of trumpets and trombones (and tubas and horns) out into the seats and steps of the hall, a raucous and ecstatic energy carried the piece to a close and the audience to its feet.

After a standing ovation that lasted for three separate bows, the Canadian Brass returned to offer two encores. The first encore featured Canadian Brass member and Lexington native Caleb Hudson showing off the infamously tricky trumpet solos of The Beatles’ Penny Lane. Canadian Brass also demonstrated exactly how fast their fingers could move with a second encore, featuring The Flight of the Bumblebee in an all-brass arrangement.

The final notes shot by at such a rapid clip that the audience had to give another standing ovation just to capture them as they flew by.Â

Many left the hall that night buzzing with excitement over what they had just experienced.