Of all the Lexington painters who’ve developed a signature style over many years, Clay Wainscott stands out. Wainscott’s paintings are immediately, obviously, indisputably his, even from long distances away, even at a glance. Last year, when he had a group of paintings of overpasses hanging in Arts Connect’s Windows Gallery on Main Street, people who zipped past in their cars, catching mere glimpses of the work in their peripheral vision, reported to him that they’d recognized it. This instantly identifiable quality is all the more striking because it seems entirely unrelated to his subject matter, which is all over the place: architecture, animals, people, street scenes, restaurant interiors, flowers, furniture, automobiles, and on and on. “It’s recognizable, and it doesn’t look like anybody’s else stuff,†Wainscott says in an interview in the spacious studio in downtown Lexington where he has worked steadily for more than four decades. “But I don’t do that by picking out a motif and repeating it over and over again.â€

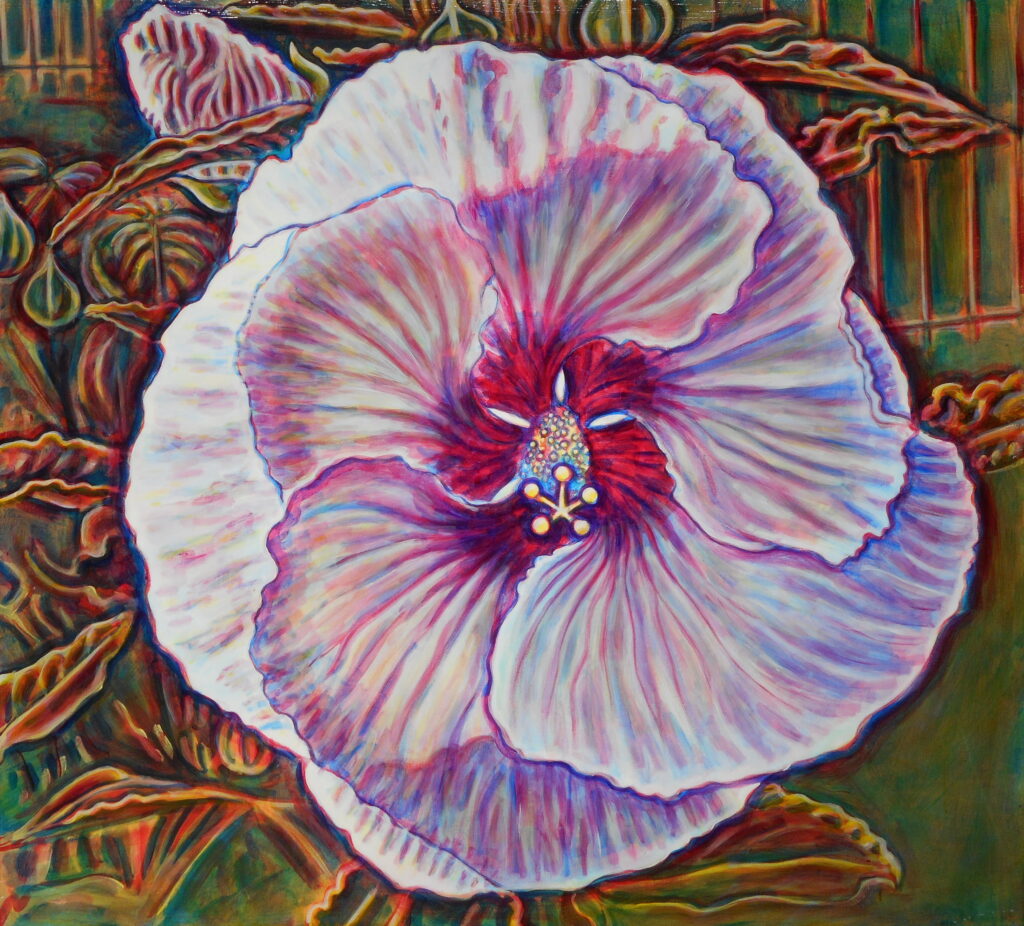

He does it, instead, with a bespoke painting method that in turn has produced a large and remarkably consistent body of work in which his wide-ranging subjects all receive what might be called the Wainscott Treatment. Drawing on his early experience with screen printing – a process that involves overlaying multiple plates – Wainscott paints by applying layers of red, blue, and yellow acrylic paint to his large canvases, one color at a time. These primary colors are diluted with a polymer medium to the point of transparency. Stacked on top of one another, they meld and mix and transform, achieving varying degrees of opacity with the addition of white. The secondary colors – plummy purples, bruised-peach pinks, precious-stone teals, earthy burnt oranges – float up through the overlaid primary colors from back to front. The transparency and thickness of the built-up surfaces, reminiscent of some forms of encaustic painting (occasionally you can see the weave of the canvas through the layers), produces an eerily resonant, glowing effect, like stained glass lit from behind. Shapes are often delineated in ghostly white outlines like those seen in X-rays or the chalk drawings left by police at crime scenes. On display under soft light in dim rooms, the paintings have an almost ghostly luminescence. And the more you look at them, the more they seem to pulsate in their frames, emitting an electric, otherworldly frequency all their own.

And conjured by means of this technique – in which he applies “the principles of abstract art to making referential pictures,†as he describes it on his website claywainscott.com – his deliberately mundane subjects come to seem like magical, perhaps talismanic objects. In his best work, the ordinary is transformed into, or perhaps simply revealed as, the extraordinary. Viewed through Wainscott’s Technicolor night-vision goggles, the most common of household objects – like the one in “tea kettle†(2004) – feel surreal, almost phantasmagorical, yet intensely present. In “coffee†(2013), a mug on a table in a diner takes on something of the gravitas of a mythic grail. In “hibiscus†(2018), a flower seems to bloom hypnotically, almost erotically, before our eyes. In “bus†(2014) and “melon lady†(2015), shadows become at least as interesting, with even greater density and depth, as the human figures who cast them. What we barely looked at before, because it was always boringly there, becomes urgently, insistently there, compelling our attention. “I’m not painting the thing as it is,†Wainscott says. “I’m painting the thing as it’s perceived.â€

But the most fundamental aspect of the uniquely cohesive quality of Wainscott’s work – the thing that makes its signature so legible, even though he doesn’t actually sign his paintings – is its elaborate philosophical armature. Although largely self-taught, Wainscott, now 77, may be the closest thing Lexington’s artist community has to a true public intellectual and art theorist. Interviewing Wainscott about art is at once a challenge (mainly because of his often circuitous manner of answering questions) and a rare pleasure. His conversation is always lively and thoughtful, full of art-historical references, anecdotes, and complicated metaphors. It can also be spiked with harsh judgments (“If you put a [Willem] de Kooning up next to a painting a cow made, even de Kooning couldn’t tell the differenceâ€), bitter grievances (he refers to publicly subsidized art as a form of “charityâ€), and the occasional F-bomb; he can still curse like the Vietnam-era soldier he once was. The politics of the post-war American art scene, dominated in his view by a misguided preference for abstraction over representational art (and for “academic†over “independent†artists such as himself), comes up a lot. “I’ve always kind of felt that I might have an audience that I was being held away from,†he says, “and I felt they were being held away from me.â€

Another frequent topic is prehistoric art, such as the cave drawings at Lascaux and elsewhere, which he venerates as touchstones and direct precursors of his own practice. “Why did the caveman paint the antelope on the wall?†he wonders out loud one afternoon at a Lexington coffee shop. “Was it to show us an antelope? Or was it to say, I was here?†He smiles. “This is me, too, of course. I paint because I only had one ticket, and I didn’t want to be an insurance salesman. I just wanted to justify myself, justify my time here. I’m mostly happy with the way it turned out. I’ve lived the life I wanted to live.â€

However roundabout his thinking, Wainscott always circles back to his main theme, which centers almost obsessively on the nature and potential of human vision. “Since early on, his work has been very much concerned with optical reality and how people perceive it,†says Logan Dennison, former exhibitions director at the Lexington Art League who curated a career retrospective of Wainscott’s work – to date his first and only large-scale solo show – at the Art League in 2019. “He’s had such a laser focus on that concept that it appears to have kept him going over the years in the absence of a lot of outside validation.â€

Worked out over a lifetime of thinking and writing and painting, the principles that govern Wainscott’s ambitious, essentially cerebral art practice have to do with the ability of great art to commandeer the viewer’s attention. It snaps us out of our fog of distractions and forgetfulness and indifference, he believes, and thereby forces us to see something, really see it as the artist sees it, in all its vivid, scrupulously observed, suddenly strange detail. “If something is not essentially important to us, we let it go,†he says. “So what I’m reconstituting are visual elements that are always present but go unregistered and disregarded in everybody’s vision because they don’t affect us in any way. That causes a great confusion in the attention threshold.â€

The resulting paintings, he believes, have a cumulative effect on their owners. “If the painting is interesting enough and seductive enough to not fade, it’s going to stay with you,†Wainscott says. “The couch is going to turn over every ten years, you’re going to move to another apartment, whatever. But the painting is going to be there in your consciousness. It’s going to burrow in, the longer you have it. People who own paintings for a lifetime don’t want to give them up, because it’s kind of a testimony about seeing the world.â€

And once Wainscott’s work has your attention, his even more ambitious goal is to tempt the viewer to train his or her extended, heightened, refocused vision on the world outside the frame.

“Say you’re a harried city person, and your senses are all beaten back into your head because you drive home during heavy traffic for an hour,†he says. “You’ve got this routine, but you take a Saturday off and you go to the art museum and stand for half an hour in front of a Winslow Homer painting. When you get back to the parking lot, you will hear birds singing. They were singing when you went in, but you didn’t pay attention. Back in the parking lot, you’ll see clouds in the sky. There were clouds in the sky when you were out on the freeway, but you never looked.†He smiles again. “This is the business I think I’m involved in.â€

Wainscott grew up in Florence, Kentucky, then largely a bedroom community of Cincinnati. His parents worked in retail. His mother, Annie Wainscott, was a fashion artist, creating pen-and-ink drawings of clothing on mannequins for use in department store advertising, and eventually had a one-woman show of her work at the Cincinnati Museum Center at Union Terminal. “But I didn’t consider art as a young person because the first imperative was to go out in the world and make a living,†he says.

His youth was difficult for reasons he declines to discuss in detail, except to say that it left him “too damaged to compete with people who’d had a decent upbringing.†His complicated feelings about his mother, who died last year at the age of 104, are on simultaneously subtle and vivid display in “Annie,†his masterly portrait of her from 2010. Wainscott insists that he is “not primarily interested in subject matter,†and that his paintings have no narrative or special meaning for him – “they’re just what you see,†he says – but his paintings of people, “Annie†in particular, seem to contradict this.

After being drafted into the Army in 1966 and serving in Oklahoma as a computer technician, Wainscott moved to Lexington in 1970. Taking graduate seminars on the G.I. Bill, he eventually settled on art as a course of study and, more important, a kind of self-therapy. “My life at that time was fairly chaotic,†he recalls. “What art offered me was the opportunity to have a thought and to see it manifest itself immediately. So what I’m doing with art initially is, I’m trying to connect myself back to the present moment.â€

He started working at a local print shop, making window banners for grocery stores, custom wedding invitations, and the like. He began to produce screen prints and posters for local businesses and institutions, including Lexington Children’s Theatre, ArtsPlace, and the University of Kentucky Theatre, and personal projects such as a series on the angular architecture of Rupp Arena. In 1979, he rented a studio at 122 N. Upper Street, perhaps the oldest building in downtown Lexington. The garret-like suite, where he has worked ever since, includes separate rooms for painting and print-making as well as a gallery across the hall where he shows and sells his work by appointment.

Initially, he paid the rent with a variety of part-time gigs, including carrying equipment for filmmakers, servicing voting machines, and designing and carving gas log sets for fireplaces. (He’s quick to point out that he had help from his wife, Donna Wainscott.) After a decade, he gave up screen printing and devoted himself to painting, pursuing it to this day with single-minded focus, often to a soundtrack of mellow jazz from the 1950s and ’60s. As a younger man, he would often do paid gigs (screen-printing posters, say, or carving fireplace logs) in the morning at the studio and paint in the afternoons and evenings, often eight hours or more at a stretch. These days, technically retired, he paints at most three hours in a single sitting, he says. “But I seem to get as much done now as I used to get done in eight to ten hours.â€

The fact that Wainscott is a self-professed loner (“I’m pretty solitary,†he admits) lends itself to art production but not at all to self-promotion, networking, or other aspects of marketing that many artists, especially those working without the benefit of academic salaries and support systems, find necessary. “It seems like he was never concerned with selling,†Dennison, now an artist and consultant in Asheville, North Carolina, recalls of the Lexington Art League exhibit. “It was more about knowing his value, knowing his mission, and sticking to that. It’s on that level that I fell in love with him. This was an artist who hadn’t been given a voice for decades, and I was trying to give him a chance.â€

Dennison was one of the few. In more than forty years as a working artist, Wainscott has received almost no media attention, locally or otherwise. Nor is he a frequenter of gallery openings or galleries themselves, regarding them mostly as indifferent or hostile to him and his work. (“Approach a gallery and they don’t look at your fucking art,†he says. “They want to see a resume.â€) Instead, he has mostly displayed his work in local businesses, such as restaurants and Marcie Rushing’s hair salon on Max Alley, and more recently at alternative venues such as Base249 and those offered through Arts Connect’s Mobile Gallery program, which displays artists’ work on a rotating basis at corporate lobbies, medical waiting rooms, and other locations around town.

“Like many artists, Clay tends to hide his light under a bushel,†says Arts Connect’s executive director, Kate Savage. “It’s also the case that he has spent a long time diligently developing his own style, but he hasn’t necessarily been given his due and been recognized as he should.â€

On the other hand, Wainscott’s feeling of estrangement from much of the local art scene – his essay in the catalog for his Art League show was titled “Return from Exile, Having Never Left†– hasn’t stopped him from getting on with the business of painting. He has pursued it doggedly, defiantly, and with an increasing confidence that’s clearly visible in the work. “I’m kind of a renegade,†he says, and if anything, he seems to have used his outsider status as fuel for his artistic fire.

“I was in bed one night in the early ’90s when it dawned on me that there wasn’t really any way that I could compete with the academics,†he recalls. “They had everything paid for, they had salaries, they had their own galleries. Everybody called them artists. It was some academic who wrote the reviews, so they had a monopoly on that, too. So I thought, This is impossible. It can’t be done. So I either had to bail or I had to double down and say, I’m going to fucking do this until they carry me away.†He pounds the table. “And I’m still here.â€

His longtime friend Dennis Meade, a jewelry designer with offices just down the hall from Wainscott’s studio, has spent many hours there with the artist over the years, watching him paint. “At some point, you stop relying on other people for validation, and that’s where Clay is at,†says Meade, who owns nine works by Wainscott, including three of his paintings. “It’s a higher impulse or inspiration that’s guiding him. He’s fairly reclusive, true, but there’s a tremendous world percolating inside him, motivating him. His belief system is like a mythology, almost a religion, and has to do with trying to help people feel and think. He has his calling in life, which is his painting. He didn’t need an audience.â€

Wainscott agrees, proudly. “I never went around patronizing or pandering,†he says. “I had a vision that I felt was important, and I didn’t go looking for an audience. The artist sweeps the floor and turns the lights on, and essentially sets himself against the whole world. And it’s like walking on a knife edge, always has been.â€

But Wainscott has looked for an audience, at least in his imagination, and certainly in his writing, where he has spent years envisioning it, perhaps trying to will it into existence. Since 2010, he has posted hundreds of short, elegantly written essays on his blog, owningart.blogspot.com, many of which posit an almost mystically symbiotic relationship between original paintings (preferably by local artists) and those who buy, love, and live with them. Wainscott’s goal is to help them “reclaim your ability to see for yourself what the world has to offer,†he wrote in January. “A successful work of art resonates, rings in the senses like a tuning fork, a deep visceral sensation never fully described in words. Works of art can suggest new possibilities to tired, bored eyes, and like water in a dry window box, can cause new growth to appear in the form of more detail and texture in everyday life.â€

Wainscott is deeply contemptuous of what he sees as the ridiculously hyper-inflated international art market, in which paintings by blue-chip artists such as de Kooning and Mark Rothko fetch outlandishly high prices of $50 million or more from wealthy collectors who view their purchases as financial investments. His own paintings – mostly large square canvases of around 42 by 42 inches or so – go for around $3,500, which is on the higher end of the price range for work offered by most Lexington painters. (His early screen prints, generally more abstract and graphic than his paintings, can be had for around $250.)

“I think that people own original serious art because it enhances their life, not because they’re collecting poker chips that they can trade up all the time – that’s just absolute horseshit, I’m sorry,†Wainscott says. “Art is, seriously, an investment in yourself. If you spend $5,000 on a painting, it’s because it’s worth $5,000 to you. You’re not buying a riding mower. You’re saying the painting is more important because, for the next 40 years that you own this painting, it’s going to make your life better than that damn machine that’s going to cough and fall apart in the next three years. You’re also saying, ‘I don’t care how much this painting is worth on the market 40 years from now. It’s part of my life.’â€

Top image: A photo of Clay Wainscott sitting in front of one of his paintings looking directly at the viewer. The painting depicts the front of an off-white truck. Photo by Kevin Nance.