First Studio Visit

Gaela Erwin is not a traditional portraitist. She is not in the vanity trade. She makes likenesses but her subjects are generally close friends or herself. Most commissioned portraits celebrate status, and their predominantly male subjects are attired in religious, academic, or judicial robes, or military uniforms bedecked with ribbons, medals, and gold braid. (When men are doing something important, they often wear either dresses or ornaments telegraphing their biographies). Those pictures are intended for ceremonial settings and bespeak heritage and the presumption of patrimonial inspiration. Erwin, in contrast, doesn’t make art that serves a public function. She is free from worries about a nabob’s imagined self-image. The “artist’s unstoppable urge to complicate that self-image and the expectation of whoever ends up with the result,†in Simon Schama’s phrase, is not an issue for Erwin in terms of a possibly disgruntled patron. Indeed, the urge “to complicate the image†is the point. “It’s like the oyster with a piece of gravel,†she observes. Ideally, the irritant is slowly layered with a nacreous shell and becomes a pearl.

Likeness is only a departure point for a protracted negotiation, a doubled path of discovery of some truths about the sitter’s being and the artist’s self-awareness. Erwin learns more from people she knows than from strangers. There is nothing pat or predetermined about how she goes about her picture-making, and it has continually evolved. Nonetheless, she is deeply engaged with the art history of portraiture and draws widely from it.

Gaela has lived in a large 19th-century house in Louisville’s Original Highlands neighborhood since 1985. She has been divorced once and widowed twice. She lives with Pfanny, a Chinese Crested dog, whose fixedness in the lap of whomever Erwin is painting helps to keep the subject stationary. She has a second-story studio with a skylight and eight windows. Props, including costumes, stuffed birds, a box of animal bones, skulls, and a manikin, are scattered about the studio along with paint and paintbrushes, seven work tables, house plants, anatomy books, and shelves stacked with art supplies. There are three easels. Recently completed art or works in progress surround the primary work area at one end of the room. It’s an unadorned, real workplace.

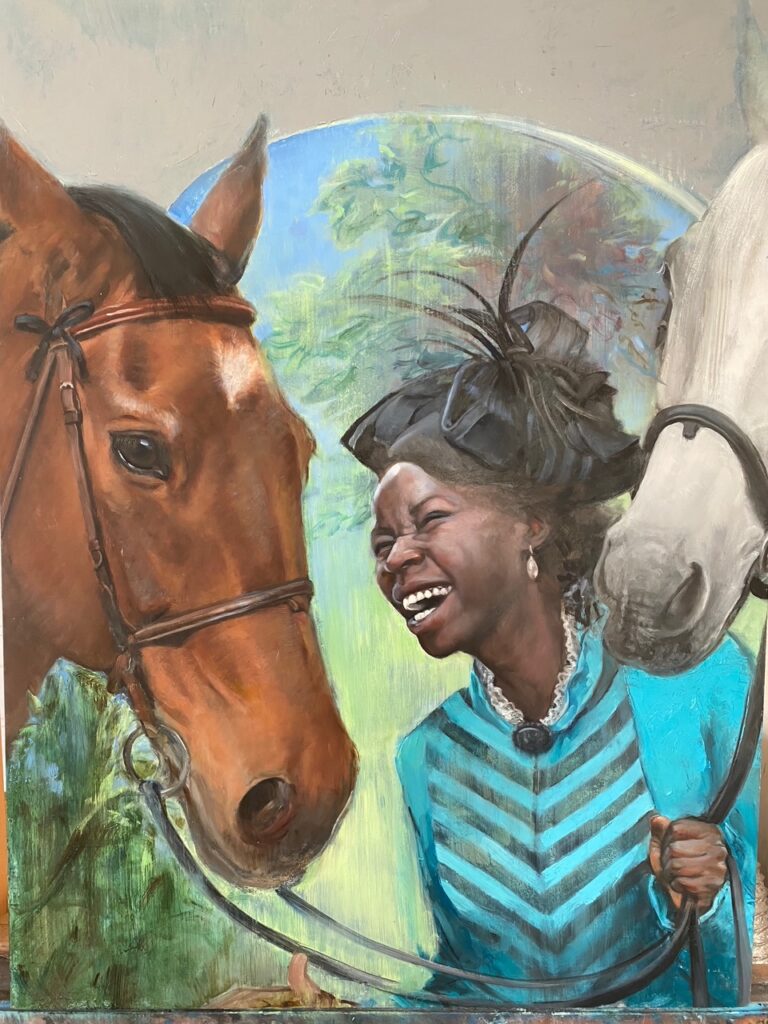

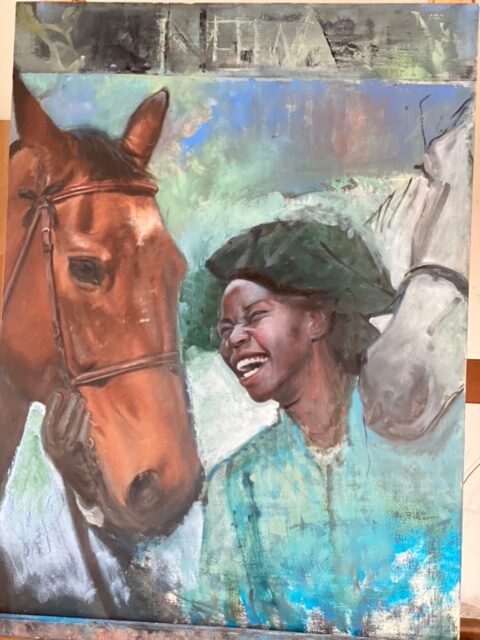

On my visit, Gaela declared that she was finally finished after 18 months with Neema, a painting of Neema Tambo, a friend and model from Uganda who died tragically at the age of 23 from myeloma. Tambo, sunny and giddily gleeful, is seen in a protective oval formed by a pastel-hued spring landscape in the background behind her, two flanking horses’ heads and the loop of the reins of both horses she holds. She is seen straight on, wearing accoutrements that connote wealth and status. She wears an elaborate 19th-century equestrienne’s hat, an 18th-century pearl drop earring, and a Victorian afternoon dress. A black mourning ribbon is attached to the bridle of the chestnut horse to the left and a black mourning brooch is at her neckline.

The late bell hooks wrote of depictions of Black women:

“Creating counter-hegemonic images of blackness that resist the stereotypes and challenge the artistic imagination is not a simple task…Images that are counter-hegemonic are necessarily provocative, their seductiveness, their allure lies in the freshness of insight and vision.”

Erwin describes the relationship between the painter and the sitter as comparable to the attraction of two lovers, gazing into one another’s eyes for extended periods. In this fantasy, Neema is transposed to the 19th century: she could readily appear in one of the watercolors of Constantin Guys (1802-1892), the artist celebrated by the critic Charles Baudelaire as “the painter of modern life.†According to Baudelaire, Guys delighted in “fine carriages and proud horses, the dazzling smartness of the grooms, the expertness of the footmen, the smooth rhythmic gait of the women, and the beauty of the children, happy to be alive and nicely dressed – in a word he delights in universal life.†The watercolorist was attuned to minute variations in women’s fashion, like a 19th-century Bill Cunningham or André Leon Talley. Baudelaire’s descriptions fit Erwin’s program.

Erwin embeds the deceased young woman in cultural memory, and positions the imaginary historical condition as a healing text. In inventing a fashionable setting for her model a century and a half in the past, Erwin in part reflects her own predilections. The chestnut horse to the left is a portrait of Willy, a horse that Erwin rode for twenty years in her weekly “equine therapy.†The horse on the right is an expensive Lipizzaner. Erwin’s innumerable alterations to the painting – which include every element of the composition – recall the poet William Butler Yeats’ explanation of frequent revisions of his poetry: “It is myself that I remake.â€

Second Studio Visit

The artist is proud of the last addition to the portrait of Neema, a thick swipe with a loaded palette knife on the right side of her dress, giving her more prominence in comparison to the surrounding horses, and creating a dynamic torque to her torso. Erwin struggles to suppress a desire to overload her paintings with details – “details for details’ sake.†She is attempting to work more abstractly, dodging fine gradients and point-to-point inflections for a broader, blunter touch. At the same time, she remains fascinated with specific problems in realism, for example, the mimetic treatment of textiles, how to make perceptible the weight of cloth, and how to transform the materiality of stuff into pastel or oil paint. For a painting of her younger sister, Shelly, who lives in California, she had a bedspread mailed to her for close study. (Shelly: California Dreaming). Objects with half-understood or private associations and meanings, or people intertwined with the artist’s life, dominate in Erwin’s art.

Erwin’s repeated paintings of her mother and sister problematize what it’s like to be in a family. She describes these pictures as “alleviative.†Painting your relatives furnishes them the comfort of being fully seen, a measure of honor and validation: but it also may muddle with the contentious complexities of family ties. Both the tenderness and discomfort of familial intimacy and friendship are evident in Shelly: California Dreaming. She is slumped limply on her side with her face, right shoulder, outstretched arm, and hands highlighted. Like Henry Moore’s sculptures of reclining nudes, the figure takes on the irregular massing of a landscape. The light falling from the left obliterates the color on the right side of Shelly’s face. Comparably, the illumination of her blue-green sweater moves from tint to tone to shade as does the shadow on the blue coverlet. As value and intensity of the colors shift, the brighter areas of the sweater on the left and the coverlet on the right bracket the darker modeling passages. The deployment of color, shape, and composition focus attention on Shelly’s face and its expression of apprehension. Lofting the figure into the top third of the picture accentuates her vulnerability and isolation. The family images are never nerve-grating: the sense of sympathy is profound.

A Memory

A third painting in the studio particularly resonated with me because I was present at its genesis. Ann Stewart Anderson, a feminist artist who specialized in collage late in her life, was in hospice care at Norton Pavilion Hospital in Louisville at the end of February and the beginning of March 2019. Her voice was reduced to a whisper, but she was mentally alert, responsive to visitors, and had all her faculties intact. Her caring husband, Ron Mikulak, emailed close friends inviting them to visit and bid a final farewell. Mikulak and Anderson were extraordinarily generous in their invitation. I remember being struck by how remarkable and deeply joyful it was that she was still able to take pleasure in our visits. It was a gift for the visitors and for Ann Stewart Anderson.

I was present when Gaela came, and with Ron’s and Ann Stewart’s permission, she thoroughly photographed Ann Stewart, much to the dying woman’s pleasure. Gaela and Ann Stewart Anderson had for a time spent Saturday mornings together canvassing yard sales, and it was as if the two artists were collaborating on a work that could only be completed after one of them had died.

The portrait of Anderson could have been contrived as an allegory, but Erwin insisted instead on Anne Stewart’s palpable presence and ironic vitality in her last hours. Erwin photographed her from every angle but, in the painting, Anderson is seen upright and slightly from below, ensconced in a tondo format reminiscent of 18th– and 19th-century ancestry pictures. Once again, Gaela totally re-worked the painting and began anew. “It started out very tight but then became looser and more driven by feeling.â€

Anderson is seen on the left of the circular panel, her face balanced against her hands to the right. There are electric El Greco-like highlights on the pink bed jacket and her outstretched hands, tangles of black veins and red-orange flesh: the hands carry much of the emotional weight of the painting. Their foreshortening makes them appear oversized: they are seen vividly against a complementary-colored blue-green blanket. The dying woman’s head nests in a white expanse of gray and white floral bedsheets which merge in color with the brushing fall of her wispy hair and a shawl around her shoulders. She appears as if sinking into a white void (a pillow behind her head was deleted from an earlier version): she is held to the foreground by the eloquent hands below, and the matching coloration of the face and hands.

The animated brushwork in this painting has an expressionist sense of urgency, as if the exigent circumstances of its making were based on a live model rather than photographs. But perhaps its greatest invention is its disequilibrium, so that Anne Stewart Anderson appears almost off-kilter. From the painting’s center, she is angled backwards (her head) and forwards (her hands). Stretching the primary points of attention across the picture surface endows the subject with an ambiguous sense of animation, reinforced by Erwin’s highlights in the eyes, lips, and the luminous modeling of Anderson’s head, counterweighed against the bravura painting of her hands. Equilibrium is rescued at the last moment.

Erwin captures the contradictions: Anderson’s lively interest and enjoyment of her visitors, her diminished state, and her seeming acceptance of her fate. Erwin’s remembrance remains grounded in observation but is also a distillation of grief, an internalized script, and an arresting moment of suspended time.

Third Studio Visit

Gaela Erwin is best known for her long series of self-portraits. My third visit was during a blinding rainstorm, and the studio was dark. The backflow valve on the 19th-century sewer had failed and the repair would necessitate a deep excavation of the garden. It might have been a somber visit, but Gaela was remarkably upbeat. My attention was riveted on a recent picture that had gone particularly well and that Erwin had not lingered over. In Covid Self-Portrait, another round panel, she stands entwined in surrounding blue bars or bands, somewhat reminiscent of the cages that encase the subjects in some early Francis Bacon paintings. But the composition also offers a riposte to Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing of the Vitruvian Man, an idealized male nude inscribed within a circle and a square. Erwin poses herself as if exercising, perhaps doing trunk twists. The presentational immediacy of the image emphasizes her physicality, especially through her shoulder and upper arm muscles, tensed at either side of her face. Her striped top completes the geometrical abstraction initiated by the blue lines. The painting had been completed with few revisions: “I’m always pleased when I don’t perseverate,†she remarked.

What happens when a female artist is on both sides of the easel, as both model and painter? In Gaela Erwin’s case there is a deployment of ingenuity that undercuts the male gaze and the objectification of women that is a main current of western art history, but also an adamantine struggle to assert the unblinking lived reality of conscious life. She shows herself breaking the frontal picture plane, seemingly thrusting her head into the viewer’s space. Erwin’s long series of self-portraits have an inherent narrative base: stories have to be repeated over and over, because it is so easy to lose richness, depth, and complexity, and familiarity opens up the threat of erasure. Furthermore, for an artist as fluent and inventive as Erwin, all self-projections are provisional and liable to give way or break. How to get beyond the short-term – how to craft continuing artistic reassurance of one’s existence – is an ever-recurring challenge.

Field Trip

The visits to Gaela Erwin’s studio took place in January and February 2022. She and I also had a field trip in January to the studio of Aaron Lubrick, her fellow graduate of the Columbus College of Art and Design. They commiserated about the need for revision and the challenge of knowing when to stop. Gaela and Aaron agreed that the space around shapes was more important than the shapes themselves and that some of his landscapes needed to be “aerated,†provided ventilation and relief from an allover density of paint. Erwin recommended sanding down and repainting particular areas between tree branches to lessen the contrast between built-up areas and others that were more thinly painted. “Some works have to be stepping stones,†she said. “Kill your babies. I have been known to feed a dead horse. I set myself up in a number of ways. When I go down a rabbit hole I get halfway to Beijing.†She now plans to accompany Lubrick on painting excursions to Cherokee Park in Louisville to do alla prima wet-on-wet oils, to be finished in one go. She intends them to serve as a corrective to her laborious process and inclination to delve into detailed fact.

We are privileged to watch an artist judiciously experiment, varying degrees of linearity and painterliness, focusing in or pulling out from the panel or canvas surface. Not being able to work from life because of Covid has been an enormous challenge. For many painters, including Erwin, the richness of the cross-pollination of person, place, presence, relationships, culture, and art shrivels up if limited to the vicariousness of photography, like a courtship conducted solely on Zoom. Erwin discussed her preference for working directly in the presence of the model: “Working from life you have to short circuit, moment by moment, catching what you can. Shorthand leads to vitality. From photos there is no limited time. You don’t have that insistent vibration from the sitter.â€

The rewards from the encounters with Erwin’s recent art are many, but foremost among them is their emotional and psychological authenticity. They are convincing in their depictions of joy, grief, inwardness, acceptance, and resolve.

The viewer is engrossed in the pictures of Neema Tambo, Anne Stewart Anderson, Shelly Erwin, and Gaela Erwin herself because of implied narratives that are adumbrated but remain unsaid, and because even in the fantasy of a 19th-century sanctuary for Ms. Tambo, an everydayness is retained. These are pictures that convey urgency and whose structures are unfailingly controlled yet elastic in their depiction of figures and their encompassing arenas.