For the last year, interdisciplinary artist Josie Love Roebuck has been working out of her one-bedroom apartment in Villa Hills, Kentucky. It’s been a challenge. She laments the lack of space, the carpeted floors now stained with ink and paint, the distance to her job as an adjunct professor. She worries about receiving noise complaints from neighbors as she drills into wooden panels and hammers into walls to hang her works-in-progress and completed pieces. She misses the community of artists inherent in graduate school shared-studios. She wrestles for control of her yarn and fabric supplies with the other resident of the home/studio, an inquisitive grey cat named Mushu.

While the scene may be familiar to young artists across the country, striving to balance a studio practice with life after academia, the setting itself creates a certain kind of disconnect. Roebuck lives and works in a sprawling apartment community in what is, ostensibly, a suburb of Cincinnati, Ohio. It has the feeling of a gated community, without the gate. The condominium and apartment complex campuses boast rolling, manicured lawns and well-maintained walking paths and water features. It’s bucolic, in a golf course kind of way. All of this creates an unexpected dissonance when stepping into Roebuck’s live/workspace and confronting the efforts of her studio output.

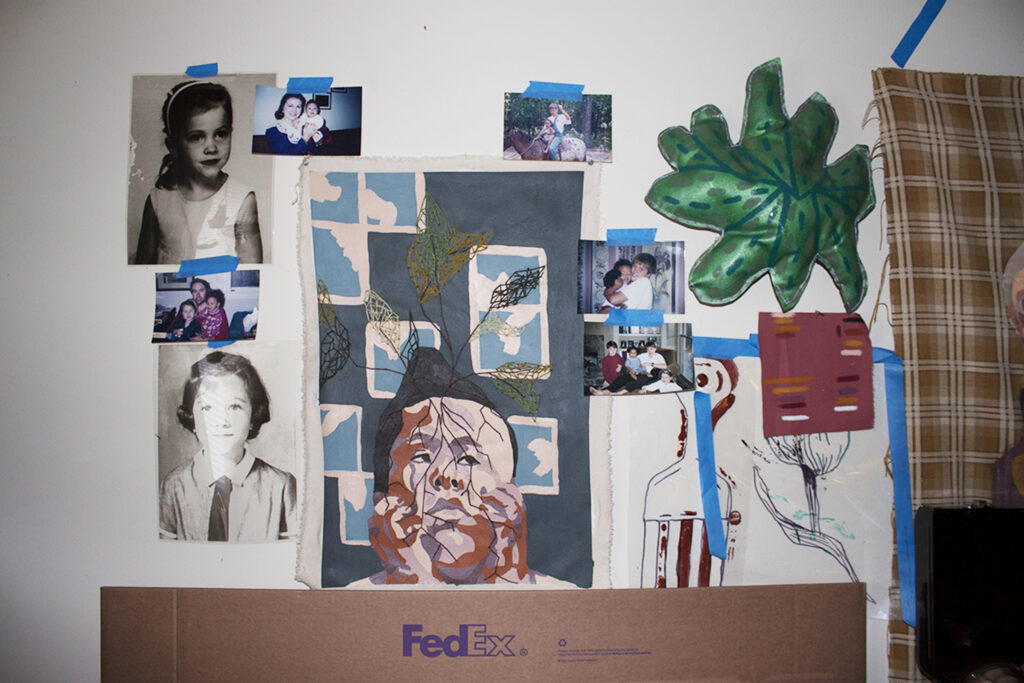

The effect is immediate. The space is small but comfortable. It is lived-in, deeply personal, yet still welcoming, inviting. The space is made to feel smaller by the sheer volume of original artworks hung, stacked, and placed throughout the residence. The curation of her finished and in-progress works straddles the line between on-display and out-of-the-way, highlighting the challenge of storing large-scale cut-outs and quilted works when space is at a premium. The sense that this place is deeply personal while remaining attached to the world at large is derived through the presence of Roebuck’s artworks, which are at turns autobiographical, narrative, revelatory, and withholding.

The works of Henri Matisse, Ebony G. Patterson, Pablo Picasso, Bisa Butler, and a childhood spent making pouches and clothing with her mother on their family farm in Georgia have all contributed to Roebuck’s development as an artist. Likewise, the quilts of Gee’s Bend – produced by enslaved women and their ancestors in rural Alabama – have had a profound impact on her practice. She relates that even though the quilts of Gee’s Bend feature abstract compositions, they still function as a kind of portrait – a document of a lived experience – communicating aspects of these women’s everyday lives. As a contemporary artist, Roebuck defines a large portion of her work as “tapestry-like quilts.†She sees herself as pushing the boundaries of a traditional medium, “By adding screen printing, acrylic paint, patchwork, yarn, oil pastel – that’s me learning from history but also kind of creating my own path forward and being able to write my own stories through that process,†she states.

Whether working on a tapestry-like quilt or a cut-wood panel piece, Roebuck’s process usually begins with an experience: a specific memory from childhood, a phrase directed at her without respect, a traumatic event. Often times she engages in research to connect a personal experience to a more common concern. “My work is showing my face and my experiences and my stories,†she relates, “but the way I’ve depicted myself, I hope that my viewers can place themselves within my stories, or take their own experiences and say, ‘Oh, I’ve felt a similar way,’ so they too can heal. It’s not just about my own healing, it’s about connecting to, hopefully, everyone, so they can experience some kind of healing through this process as well.â€

Earlier in her career, Roebuck’s work focused on the emotional destruction experienced by survivors of sexual assault. The artist explains, “A lot of times I was sharing my own stories or stories friends have shared with me…It’s about healing. It’s also kind of about reopening these wounds, and when I sew, to me, that has a lot of symbolism. It’s the act of opening and closing wounds. I’m opening this wound of sharing something traumatic, but I’m also closing it together by sharing what has happened.†This act of suturing reinforces the presence of the body in Roebuck’s work. There is a distinct physicality to Roebuck’s process. It is a quality that transfers from process to product, impacting the character of her quilts and cut-wood panels. Documentation of her studio practice hosted on her website reveals the artist in various phases of production: cutting, sewing, sawing, drilling, braiding, painting.

While much of her work could fall into descriptive categories like assemblage and collage – her pieces straddling the line between two-dimensional and three-dimensional space – Roebuck prefers to define her work somewhat strictly, even if that definition is a little difficult to pin down. She sees her wood cut-outs and tapestry-like quilts as purely two-dimensional, analogous to cut paper pieces. This view may be a hold-over from her formal training as a painter before she began expanding her aesthetic and material lexicon.

However one chooses to categorize them, her pieces are certainly pulpy – layered in with patchwork clothing rendered through fabric and adorned with oil pastel, yarn, screen-printed motifs, and additional ephemera like buttons and hair bows. Some of the materials have been reclaimed from her own childhood, while others are chosen for their resemblance to patterns of her past – plaids especially. That Roebuck’s works are so based in figurative representation, while also revealing the artist’s hand as explicitly present, illustrates a central point in her practice. She explains:

“It’s all a part of this process of creating these works, healing from it, kind of showing the pain it does to make it. Half the time I am bleeding, sewing into wood, or sewing into my tapestries – accidentally poking myself with needles – I give myself blisters all the time drilling into my wood cut-outs, but I honestly wouldn’t have it any other way. It does touch into the message that I am trying to convey into my pieces.”

To see the artist’s hand in the work creates a strong connection between the body of the artist, the bodies of the work – both within the work and of the work itself – and the body of the viewer. For Roebuck, who is interested in channeling healing for herself and others through her artwork, building this connection through corporeality is vital to the success of her efforts. She also engages both environmental and cultural symbols as further means of connectivity. Many of her works include floral motifs that represent aspects of the curative approach Roebuck takes through her practice; abstracted oak leaves for inner strength, a rattlesnake plant for finding new beginnings, mountain laurels representing perseverance, and various succulents to symbolize growth and overcoming.

Additionally, Roebuck has always been interested in using text within her work, with the struggle of incorporating alphabetical characters into aesthetic works. The text Roebuck includes may be couched into the piece, hidden within or behind compositional elements. Sometimes her text is written out in material that obscures legibility, like buttons. Other works place text prominently within the composition, highlighting the artist’s interest in narrative, biographical, and autobiographical output. The use of text is just one space within her practice where Roebuck builds in varying access points and barriers.

Spring of 2020 brought a shift in focus onto race within Roebuck’s studio practice. “A lot of people don’t know, but I am biracial, and then I am also adopted by a white family. So my work is about sharing my upbringing in a predominantly white culture, prejudice that I have faced, instances of racial remarks that others have said to me. So it’s all about healing, it’s about sharing my life experiences and connecting them to humankind.†The healing Roebuck alludes to includes a search for place within a society that often excludes multiracial peoples from the larger discourse around race and identity politics.

Roebuck has interrogated her own origin, parsing through adoption records and DNA test results to gain a sense of self and place. In the past, she had balked at questions about her racial composition, not knowing the geographical origins of her ancestors. Roebuck’s explorations into her ancestry have served to solidify a direction in her artwork. While she has uncovered a great deal of her genealogical history, she maintains the stance that she is more than her skin color, that she deserves more than assumptions, and that she refuses to be put under a microscope without her permission. These works are an effort to confront the questions people raise about her race, providing answers to inquiries she commonly receives, while at the same time asserting that the artist will only share so much. Here, Roebuck engages in a back and forth between creating barriers and invitations to understanding both her artwork and herself. This is the artist asserting control over her own identity. She explains:

“This barrier was created because people made assumptions that I identify as fully Black, and kind of grouped me into this category…But I do identify as being both halves, and I do want that to be known. Those pieces titled He is Biracial and I Am Biracial [are] about taking control, taking control of my own identity and saying if you’re going to group me into a category, here’s the category to place me in.”

One of the first works Roebuck created – in her shift from focusing on paintings depicting the stories of sexual assault survivors to interdisciplinary works exploring race and identity – was Magnificently Willful (2020), a large-scale “tapestry piece†featuring a female figure suspended upside-down. The piece utilizes yarn to act as natural hair, with draping strands of material flowing over the surface of the work, out into space, and onto the ground. The nature of the work and installation technique creates a barrier that impacts viewers’ ability to see the full portrait, thus impacting the experience of the work. Magnificently Willful is a confrontation with Roebuck’s past; it is the acknowledgment of a biracial girl growing up in a white family, in a white community, and her desire to fit in by relaxing, bleaching, and dying her hair to appear more Caucasian. Of course, the audience might not see the backstory in the final work presented in exhibition space. Instead, what a viewer is readily presented with is a celebration of natural hair, replete with various curl patterns.

Through her shifts in media and conceptual concerns, Roebuck has maintained a firm commitment to depicting the human form. Her portrayals of the human form began in earnest during her undergraduate studies, in conjunction with the exploration of emotional states experienced by sexual assault survivors. Early on, she distorted the figures by omitting facial features, an effort to hide the fact that Roebuck was creating autobiographical works. Eventually, with the rise of the Me Too movement and through personal growth and healing, she came to embrace her own image within the works she creates and the stories she shares. She built upon this process during her graduate work at the University of Cincinnati’s College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning, investigating interior settings and their connection to sexual assault survivors feeling unsafe in their own homes. A classroom experience involving racial insensitivity prompted Roebuck to begin shifting conceptual focus onto issues of race and identity. Through these explorations and output, Roebuck has come to define the body as a site of both transgression and identity. Because she is interested in uncovering and sharing stories of both trauma and joy in the human condition, and because the body is inherently and explicitly linked with human experiences of transgression and identity, the human figure remains a fixture within Roebuck’s practice. She confirms, “I’ve always been really interested in figurative work. I’ve tried getting away from it, but things just don’t feel right when I don’t have a figure to fully explain my stories.â€

In the rare instance where one of her pieces omits the human form, the body remains present through other signifiers. Most often, the body is invoked through textual representations of speech. Hanging on the wall of her home/studio are a pair of small text-based pieces that reference a comment made by Senator Mitch McConnell (R-KY) in January 2022 that seemed to imply that African Americans are distinct from “true†Americans. Roebuck brought McConnell’s words into proximity with data about her own personal history as a descendent of early English settlers, thus creating a work that encapsulates issues of transgression, corporeality, and identity.

Pulling quotes and inspiration from televised newscasts isn’t the only way Roebuck’s studio practice has been influenced by working from home. She notes that, more and more, the fabrics she chooses to incorporate in her works are bearing resemblances to textiles found in her domestic space. Historically, textile-based works have been linked to the realm of domesticity, with heavy associations to notions of “craft†and “femininity.†These associations once served as both critique and grounds for dismissal, but those outdated affiliations seem largely to be discarded within the contemporary art discourse. For her part, Roebuck doesn’t necessarily shy away from notions that textile-based works maintain at least the historical associations with craft, femininity, and domesticity. In a way, she leans into these connections not as critique, but as grounds for expansion. For her, an association with femininity and domesticity is a reclamation of subject matter. She acknowledges that the stories she shares through her work are themselves rooted within these conversations. Here, the artist has embraced specific materials to aid in the communication of specific narratives.

While her home/studio has been full of finished pieces and works-in-progress, many of Roebuck’s artworks are heading out into the world for exhibitions in the Midwest, New York City, and beyond. She exhibited with LatchKey Gallery at the 2022 edition of Expo Chicago from April 7-10, with works that continue to explore Roebuck’s experiences with her natural hair. In discussing the work, the artist refers to her personal history of traumas with hair products that left visible residue after promising to work for all hair types, the pain of picking out her hair with too much fervor, and once accidentally setting her hair on fire. For Roebuck, these experiences are balanced with reflections on the literal growth of her hair, and the symbolic growth of herself as a person in accepting and embracing that natural hair. Referring to herself and her adopted brother in the context of explaining her show, Roebuck shares, “We love our natural hair now and it’s something we’re celebrating, something that is always healthy and always growing.†Indeed, trauma and growth seem to be hallmarks of Roebuck’s practice.

Following Expo Chicago, Roebuck has a solo show with LatchKey, her representing gallery, in New York City opening in May. This body of work will focus more on the artist’s familial history of being raised on a farm, the various racial imposter syndromes she and her brother experienced, and instances of linguistic biases she has endured. The artist elaborates:

“I’ve had friends that will comment on my voice and say, ‘Oh, you sound all-white,’ or, ‘you can’t say something because you sound too white.’ Or if I tell them that I was adopted by a white family they’ll say, ‘Oh, that makes so much sense, here you are,’ and so forth. So [the work is] about kind of exploring those things and kind of overcoming certain things people have said, and ways I’ve learned to take care of myself within my white family and so forth, and different racial imposter syndromes that I had growing up with a family I didn’t look like.”

In June, Roebuck’s work will be featured in a group show at Kavi Gupta (Chicago, IL), and additional work will be on exhibit at the Kunsthalle Krems Art Museum, in Krems an der Donau, Austria, later in the year. So, while Roebuck continues to seek out her place in the world, it seems that her artwork is finding good space in the art world.

At its core, Josie Love Roebuck’s practice is about sharing stories and searching for one’s place in a society that is often rigid and uncompromising in its bifurcations and social structures. With a small sense of irony, Roebuck is searching for her place while resisting classification. In a way, she describes her work as she describes herself, as existing between categories. But Roebuck has endeavored to embrace the messiness of life and labels, a quality which is often reflected in her artwork as she pulls disparate materials into resolved tableaus. She believes that beauty and grace can be born out of struggle. In essence, she is not really resisting a label so much as being labeled. Really, she is asking for better, bigger, more inclusive definitions, and doing her best to contribute to the conversation on being while the work continues.

Top image: An interior view of Josie Love Roebuck’s home/studio. Various textile works hang on the wall, with the primary piece depicting a figure sitting and doing the hair of another person sitting next to them. Photo by CM Turner.