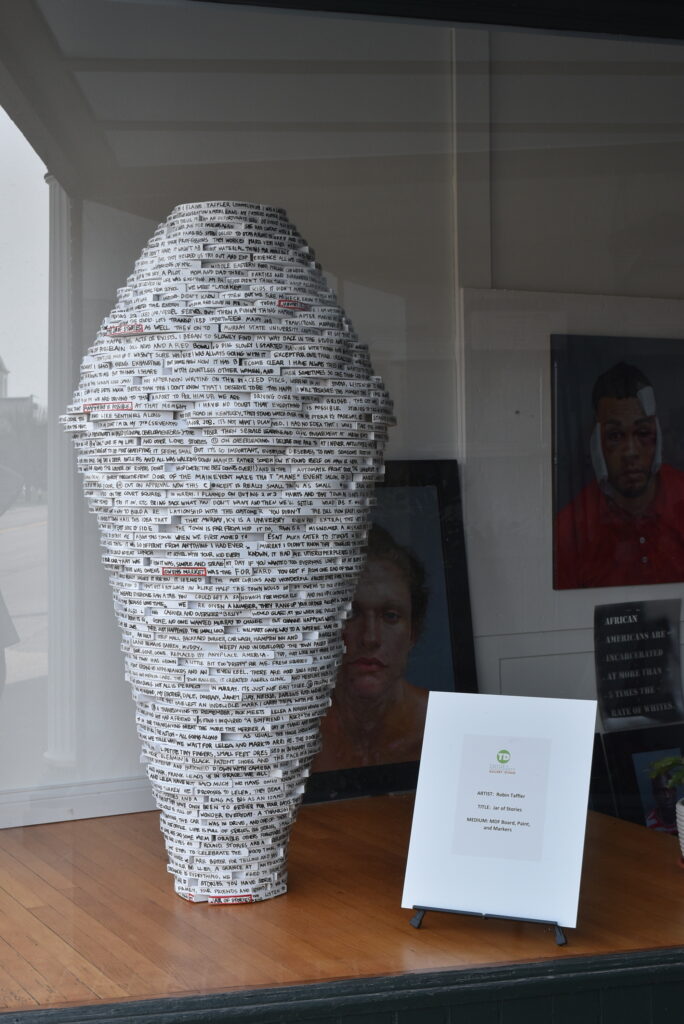

As I walk up to T&D Gallery/Studio in downtown Berea, the front window frames Robin Taffler’s Jar of Stories, a five-foot-tall sculpture. The black-on-white words spiraling around the wooden vessel compose an autobiography, a memoir of the artist’s life. It sets the stage for the studio experience by Taffler and spouse Dick Dougherty that visitors find inside – a variety of mediums and tones, but with a throughline of story.

T&D is an open studio and visitors are welcome to talk with the artists and watch them at work. The expansive and generous space centers on a mismatched living room, with Taffler’s sculpture work to the rear and Dougherty’s painting space to the front. “Having a studio in this environment is stimulating,” said Dougherty. “We enjoy people coming in as it gives us a break from our work.”

It is hard not to pick up Taffler’s infectious enthusiasm about art and life. On the day of this visit, she wore yellow sneakers and a white jacket with large black polka dots as she whisked the writer around the space, sharing her recent work. First up was a series of trophies for women inspired by a collection of found bowling pins. On Everyone Wants a Piece of Me, a flock of small birds is affixed to the pin. In Losing Shape, she reconstructed a pin of gray fuzz which has (disconcerting for this mature female writer) similarities to the shape of an older woman’s body.

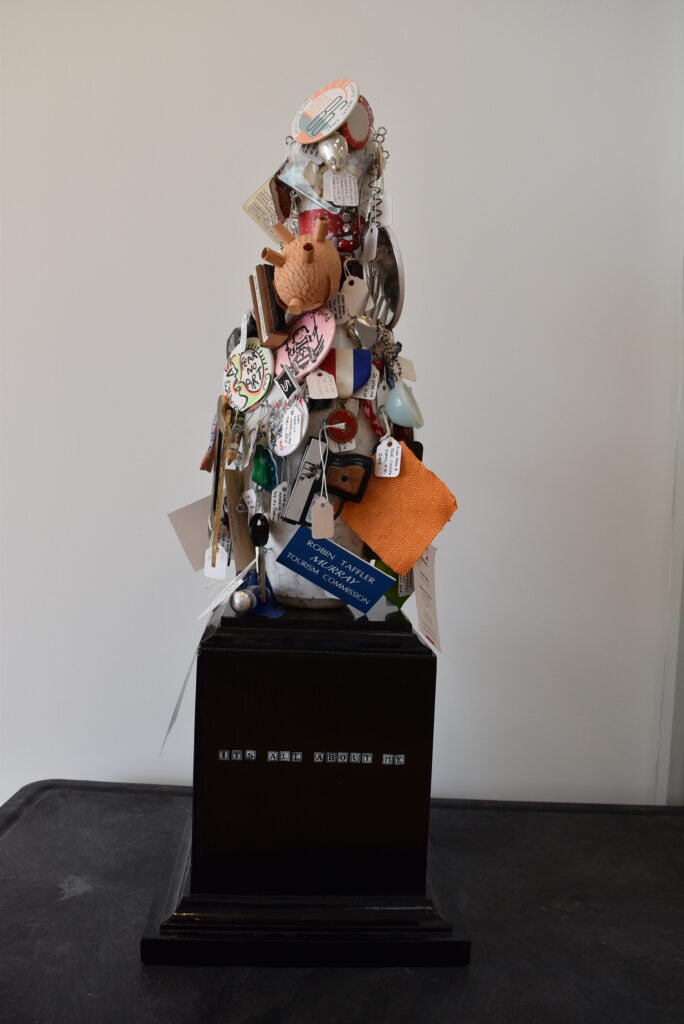

The pin is hidden on It’s All About Me as Taffler has covered it with personal tchotchkes. Each nametag, ticket stub, and cuff link is adorned with a small white tag that tells its story: “August 2006 Best time with Dick and Casey!!” and “Dad’s, wore on wedding day Feb. 6, 1954.”

Taffler keeps things like her son’s notebook from advanced chemistry and a favorite earring missing its mate because, to her, they have meaning. She elevates these small mementos into significance by incorporating them into her art. “Art is about stuff that happens, and whether disturbing, interesting, funny, or messy, it is authentic,” she said. “I tend to save everything because everything tells a story. It’s how you connect those stories that is art.”

The center of Taffler’s workspace is filled by Big Chaos, with an accompanying smaller Little Chaos nearby. The assemblage base is a colorful array of wooden puzzle pieces stacked to resemble a tornado. A chaotic collection of gewgaws is caught up in the cyclonic forces. It represents in a visceral way our collective experiences since 2020. “Life has been chaotic in ways I didn’t expect,” she said. “The pandemic added another layer.”

Entering Dougherty’s workspace across the communal studio requires more than walking a few steps; it takes a deliberate deep breath to disengage from Taffler’s whirlwind.

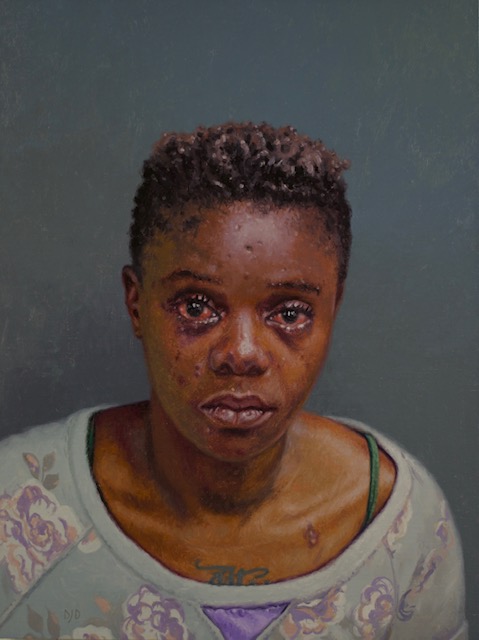

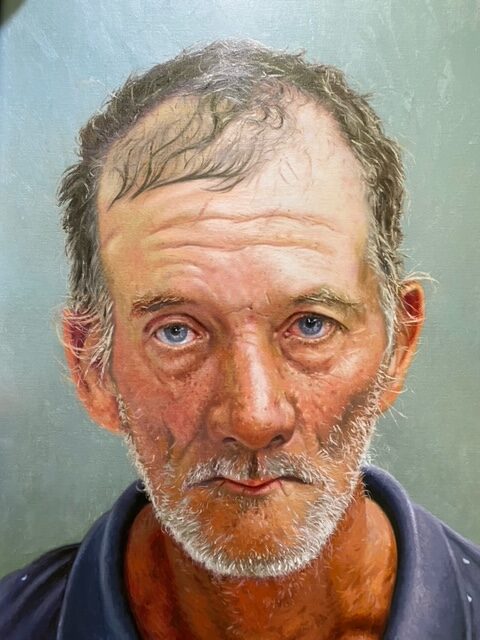

Dougherty is a painter, and for the last five years has centered his work around a series of 2700 mug shots he discovered in an online newspaper archive. In his attempts to paint emotional portraits that told a story, he was photographing friends and family but found they were missing the mark. He was drawn to these images for their emotional qualities, revealed by the unique lighting compared to other police photos.

“I was captivated and enthralled by them, but when I started, I didn’t know why,” Dougherty said. “I realized I am interested in telling their stories.”

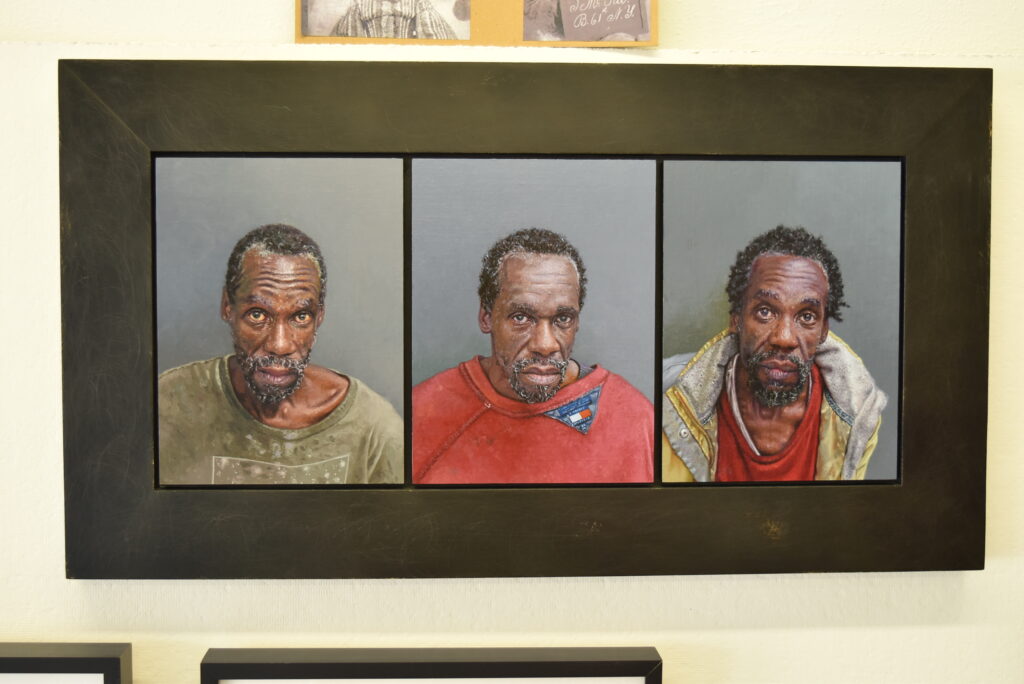

Those stories gradually unfolded as he created 70 small watercolors and now, a collection of oil paintings. He presents “The Arrested Series” with explanatory information about criminal justice reform and the impact of incarceration. The three themes he sees clearly in the paintings are homelessness, substance abuse, and the treatment of people of color by the justice system.

“I have come to see these as journalistic portraits,” he said. “There is a power in the situation of these people.”

The paintings are realistic and haunting. For the resignation in their steady gazes. For the trauma on their faces. And sometimes, for the multiple times an individual appears in the police blotter.

That repetition appears in his work Arrested: (Camping Prohibited) Roger in Three Panels, a tryptic of the same man from three different arrests. While Dougherty usually lets the portraits stand on their own, without names or criminal charges, he knows this man was arrested for being homeless.

“We should be doing other things with these people to help them rather than throwing them into jail,” he said.

Taffler grew up in New York City, the child of a teacher who painted and an electrician. They immersed her in a creative world of museums, art classes, and cultural explorations. “They made the world a curious place,” she said. “Everything was possible.”

Dougherty was not a good student academically but found his place through drawing. Contrary to the stereotypical parental response, his parents were thrilled he was attending art school. “They were just happy I could do something!” he said.

Both had formative experiences in art school as students in the 1970s and, later, as professors. They found stimulating environments that fostered their creativity. For Taffler, it was a homecoming of sorts. She learned to drive a boom truck and forklift for creating large-scale sculptures. “I finally found my tribe,” she said.

Dougherty found teaching enriched his own work. His curious nature helped him break down his artistic processes in his quest to teach students. He also learned from them as they sought out their own interests and made their own creative discoveries.

Beyond teaching, which combined they have done for about 55 years, both have strong administrative skills. The couple moved to Kentucky in 1992 when Dougherty became Chair of the art department at Murray State University. While there, Taffler became director of Paducah’s Yeiser Art Center.

The two are utilizing those organizational skills in their adjacent gallery, which they envision as a community resource. “Berea is very craft-oriented. We want to bring in art people might not see in town,” said Taffler. “Art can change how you think about things, and we want the gallery to welcome a broad and inclusive community.”

Top image: A photo of the exterior of T&D Gallery/Studio. The viewer is on the outside looking in through the front windows. Photo by Kim Kobersmith.