I.

First, I should tell you. She doesn’t like talking about them as portraits. They’re her interpretation of a portrait, of the person being portrayed.

In a way, most of us go around making interpretations of people all day, making determinations of “kind†or “grouchy†or even “beautiful†based on the particular light in which we view a person, how the person is framed, what details we choose to see.

II.

An icy January afternoon in Louisville, Kentucky. I am sitting in a folding chair opposite Sandra Charles in her modest studio at Mellwood Art Center, a former meatpacking building that is surprisingly warm. She began renting the space a few months ago; for several years before that, she was content to paint in a sunny corner of her suburban kitchen.

Charles herself is sunny, with an easy smile and a gentle laugh. She is friendly, polite, self-deprecating. Her hair: a mass of springy black curls with a faint strand of gray interlopers. Her skin: creamy brown with a scattering of freckles across her nose and cheeks. Smiling creases around her eyes, elegant burgundy and caramel glasses. Deep indigo jeans and a charcoal gray turtleneck; a black apron splattered with paint, its thin ties looped twice and tied around her small waist.

If you knew the artist, would you recognize her from that paragraph? Would you read those words and think, Ah! The writer has captured my friend exactly. What is it that we look for in a portrait? Is it mere realism, an accurate accounting of physical features? Or is it something more than identification, something closer to identity, the essential nature of this person, her habits and beliefs, the events in her life, and the choices she made that brought her here – to this place, this moment immortalized on the canvas. It’s a tricky thing, this business of representing someone’s character in a single take.

III.

Charles works in oil on canvas, in a realist manner with an affinity for the highlights and shadows that can transform a 21st-century sweatshirt into the luscious folds of cloth in a Hans Holbein painting. Her works are large – 48 by 60 inches, usually – and her subjects – Black women, always – often occupy the vertical center of the canvas, the tips of their shoes or the tops of their hairstyles reaching just out of the frame. This does not necessarily convey a proudness in her subjects, but an undeniable presence.

“Even though I don’t want to make someone look beautiful or erase her flaws, there is a little pressure to at least make her look something like who she is,†Charles says. “And it can be something simple, like the way she turns her mouth up, and I’ll get stuck on that. Somebody will walk in the room and say, Oh, isn’t that so and so? But I’ll look at it and don’t see that one thing each person has on her face, or in her eyes, that makes her who she is; then I’ll stop. I’ll step away from the painting, turn it away from me, come back to it in a couple weeks.â€

I step away from this piece multiple times over the course of writing it, worrying that I’m not adequately conveying the power of her work, that I haven’t sufficiently captured Charles’ charm, her intellect, her technical skill. Mostly, I feel unsure of myself as a white woman, naive to the Black woman’s burden of history, her feelings of otherness. “In our society, there are always the others,†Charles says. “But we’re not others, we’re humans. The joy these women feel, it’s felt by everybody. When somebody’s sad, they’re sad the same way, no matter what race. There’s a way of connecting.â€

IV.

Charles was born in Hazard, Kentucky, a coal miner’s daughter. When she was six or seven, the mines closed and the family moved to Louisville where her father found work and her mother raised her and her younger sister.“The women I grew up with in my neighborhood carried a heavy load,†she says. “My family would drive down Newburg Road and I’d see the maids standing on the corner waiting for the bus. They had to walk a long way to get to that bus stop, and be on the bus for I don’t know how long, because that bus went to the West End, where they went home to tend to their own families.â€

After high school, she enrolled in the Art Department at the University of Louisville, then paused her studies when she got married and began raising her own family. Charles resumed her artistic practice by working in fiber art, making batiks, and showing them at St. James and other local art fairs. Then, a trip to Washington, D.C. with her husband offered a revelatory experience.

“My husband’s an attorney,†Charles says, “so of course we had to go to the Supreme Court building. And when we walked in, there were these portraits of white males all down the hallway and back up. We went to several other museums and they were filled with portraits of generals and other important figures from history. And you know they’re important because they have these huge portraits.â€

Emboldened with the mission to represent the figures who were important in her life, Charles returned to the University of Louisville in 2011 to complete her B.F.A. in painting. “I thought, Well, you know what, I’m going to start making portraits. I wanted to break the rules, make my figures big to let them be the masters of their environments. They’re a little bit about me, too, because I’m making a statement that these women have something to say and they’re all important. They’re the backbone of American society and nobody notices. But you don’t see big portraits of them in D.C.â€

V.

“One of my professors would always talk about going down a rabbit hole,†Charles says, “which is when you start overworking a painting and you get to that point where you make a stroke and ruin the painting. That used to freak me out a lot. Now, once I get to that spot, I quit. And start all over again. It’s not the end of the world. It’s just a painting.â€

I look at my description of Charles and I don’t see it; there’s a word missing somewhere, a brushstroke, an adjective, a patch of color. I put it away; I’ll try again tomorrow. It’s not the end of the world.

VI.

For Esther Callahan, a Minnesota-based independent curator, arts organizer, and feminist scholar, Charles’ work is nothing less than “the transmogrification of the western art historical canon’s perceptions of Blackness and the Black female form. This work is necessary if contemporary art is to pay witness to and act on the inclusion of Black art and artists often dismissed or overlooked.â€

Once a means for royals, nobles, and other well-to-do types to demonstrate their wealth and prestige, portraiture was for centuries the nearly exclusive domain of white Europeans. Such was its power that Frederick Douglass, the revered abolitionist and statesman, believed that portraiture, especially in its photographic form, could expedite a more democratic existence, wresting “the special and exclusive luxury of the rich and great†and distributing it to all.

Of course, history holds abundant examples of rich and great Black men and women – kings and queens and nobles largely ignored by the white hegemony of Western art and literature. And, at first, Charles worked to insert these towering but overlooked figures into the canon. She painted African royalty: queens from the ancient Kingdom of Kush, from the Ashanti Empire, from Angola, Ethiopia, and the Congo. These were women Charles had chosen through her research, women she admired for their strength and wisdom, for their determination against long odds. She invited her friends to serve as models, sitting for portraits wearing the regal garments of these long-ago rulers.

The resulting African Queens series is skillfully and beautifully realized; at a glance, the subjects are stately, elegant, powerful. And yet, with time, the contemporary women behind the costumes begin to reveal their own identities. Charles told me she created the works by pairing each model with the African queen she believed most aligned with that woman’s own personality and history. The figure portrayed in “Mary as Queen Nzinga of Angola,†for instance, draped in a robe of deep crimson and wearing a crown of gold, sits with the posture of a woman who has endured a great deal, her expression happy but weary. It’s as if, in her attempt to paint the character of the queen, Charles cannot help but capture the sitter’s true essence.

Charles’ portraiture, Callahan wrote to me, “is in itself a narrative shift away from the derogatory way Black women have been depicted throughout history. It encourages the viewer to define the image of self in a new and foundational way. Her subjects are situated in a way that demands respect and dignity. It is powerful magic for transforming the way the wider world sees Blackness, Black lives, and Black culture.â€

VII.

What happened next was more powerful magic. In 2018, Charles was invited to join the inaugural cohort of Hadley Creatives, a professional development initiative funded through the Community Foundation of Louisville. Among her colleagues was Hannah Drake, a poet and activist Charles painted during the course of the program. Stripped of robes and crowns and royal regalia, “Reflections of Us†demonstrates the deepening of Charles’ technical skill as well as her changing approach to portraiture.

“With the Hannah Drake work,†says Joey Yates, curatorial director at KMAC Museum, “the background definitely became a focus. I saw her beginning to think about the context for these women, and it begins to become part of the subject matter. Where are they standing? It adds a significance and a specificity to each portrait, and in many instances, I believe, a symbolic meaning as well.â€

In the painting, Drake wears black athletic pants and a long-sleeved gray shirt, and stands almost diagonal to the viewer as she turns her head and torso toward us. She appears to be in a modern lobby of some sort, with concrete floors, white walls, and expansive windows that reflect rows of lights and columns in a muted range of white, gray, blue, and beige. There is a quiet proudness to the way Drake carries herself, intimations of interior brilliance in the orange-red flashes of the scarf draped around her neck.

The photo the painting is based on was taken in the lobby of KMAC Museum, Yates tells me, where the institution hosted an exhibition of work created by the Hadley group. At the opening, Hannah Drake read her poem “Spaces,†a stirring anthem about reclaiming places once designed by white men to exclude Black people and other minority groups. “In a way, I see Sandra’s painting fitting in with the spirit of that poem,†Yates says. “She chooses her subjects for the reasons Hannah is addressing in that poem – she’s putting images of Black women into spaces where they haven’t always been seen or welcomed.â€

VIII.

Charles often avoids naming her subjects in the titles of her works. When I ask her why, she says, “I think who they are inside or what they’re trying to say is almost as important as their name. If I name it, it becomes a portrait. And portraits are more what the person wants to say to the world, that says, Paint me like this. I really don’t want to do that, I want to paint them as they really are.â€

But if Charles is stripping her subjects of artifice and embellishment, she is also imbuing them with a kind of grace: she paints with a generosity that can render deepening wrinkles and rolls of flesh as characteristics of physical beauty, that can turn visages of apprehension and suspicion into indicators of strength. It is not that Charles is making her subjects look beautiful; it is that, to her, they are beautiful.

IX.

As Charles’ practice evolved to portray contemporary Black women, it began to align more closely with a rich tradition of Black American portraiture, including the work of Barkley Hendricks, Jordan Casteel, Amy Sherald, and Kehinde Wiley. Charles also cites the Nigerian-born artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby and the British painter and writer Lynette Yiadom Boakye as influences, as well as Edward Hopper and J.M.W. Turner for their skillful manipulation of color and light.

She was given the chance to see Crosby’s large-scale works first-hand in 2019 when she, along with Black women artists Ramona Lindsey, Lucy Azubuike, and Toya Northington, received a grant from the Great Meadows Foundation to attend the 58th Venice Biennale. It was her first time traveling outside the United States.

“I was overwhelmed by the art,†Charles says, “but one of the things I learned was that all artists are just themselves. You can be yourself, and there’s no set way to say what you have to say. I used to paint in a certain way where my main focus was the figure. But Venice changed me, pushed me off into a whole different direction. Seeing all the work and seeing how other artists tell their stories through their art gave me permission to say what I have to say, any way that I want to, and to do it without being apprehensive.â€

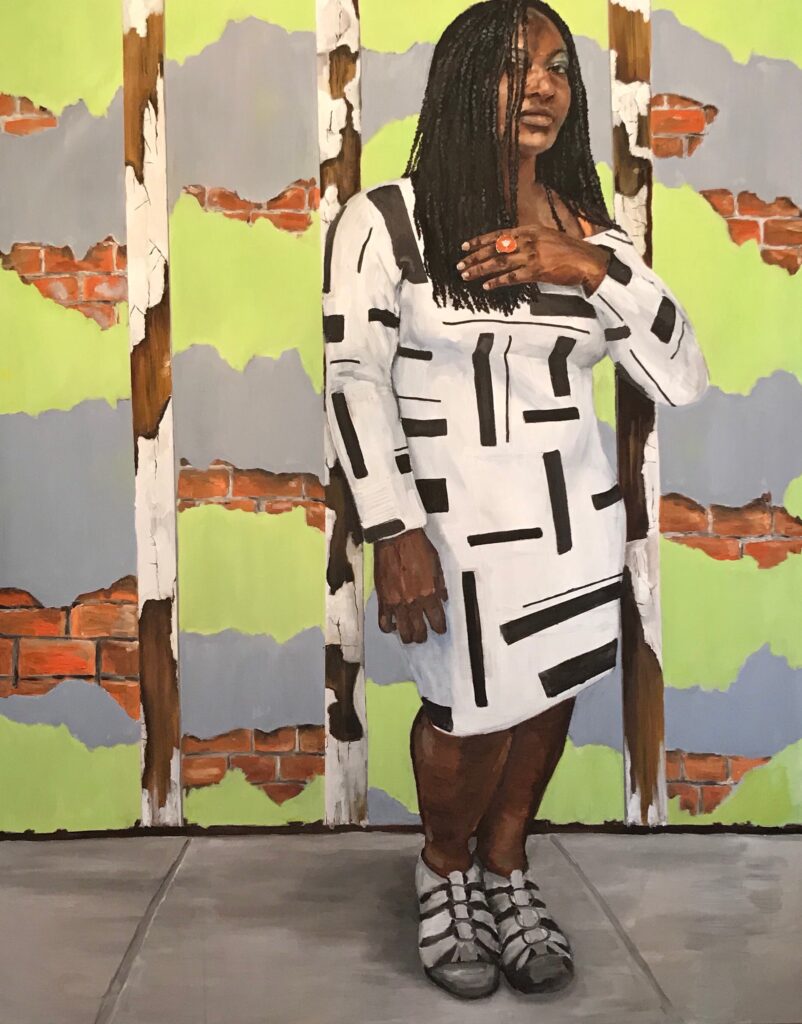

Back home in Louisville, Charles painted her traveling companions with a new intensity; the background became an extension of the subject. While traditional portraiture might have included objects within the sitter’s home to communicate their wealth and status, Charles began using backgrounds to represent the interior life of her subjects. In “Your Walls, An Artist and Venice,†for example, Azubuike appears in a white dress with a black graphic pattern, her left hand lifted to her heart. The long braids of her hair obscure much of the right side of her face as she eyes the viewer skeptically. Azubuike stands on a concrete sidewalk in front of a brick wall, on top of which are three vertical bands of wood with peeling white paint and a crumbling facade of gray and lime plaster.

“Most women – Black, white, whatever – they put up these walls so they can fit in society,†Charles explains. “In each of those paintings, the walls are crumbling to signify one’s true self coming out, and usually that true self is a brick wall that’s strong.â€

Charles, it seems, was also in the process of uncovering her own strength: “Back when I was in school, I took a painting class where they told me not to paint bricks because bricks were cliché. After going to Venice, I came back and I just started painting bricks on the walls because, you know, to heck with it! Venice gave me permission to do my own thing.â€

X.

“When I paint, there’s always a conversation going on in my head,†Charles says. “It comes from a little bit of everywhere. One of my teachers told me a long time ago, he said, painting is like problem-solving. And when I start to paint, even if I’ve sketched it and put the wash on, and I’ll look at it and I’ll say, Is that really telling me what I want to say? And most of the time, the answer is “noâ€! And that directs me to add more color somewhere, or make the figure turn a certain way. To me, it’s a giant puzzle, and inside of me, the painting is speaking. It says, No, I’m not right, and I’ll go back and add a little color, and it says, Yes, this is it.â€

I spend my days reordering paragraphs, rearranging the sentences within them, agonizing over a word that just doesn’t seem right, wondering if I’ve said too much about this, not enough about that. How much should a profile reveal about my own writing style, my own perspective, and how much should it step aside to allow the subject’s voice to be heard?

XI.

In the summer of 2021, Charles spent three months at Residency Unlimited on her second grant from the Great Meadows Foundation, along with fellow Kentucky artists Kristina Arnold and Michelle Burdine. She tells me she loved the abundance of museums and galleries, the way art felt embedded in the culture, how everybody seemed to want to talk about it. She found a renewed confidence, and new subjects as well.

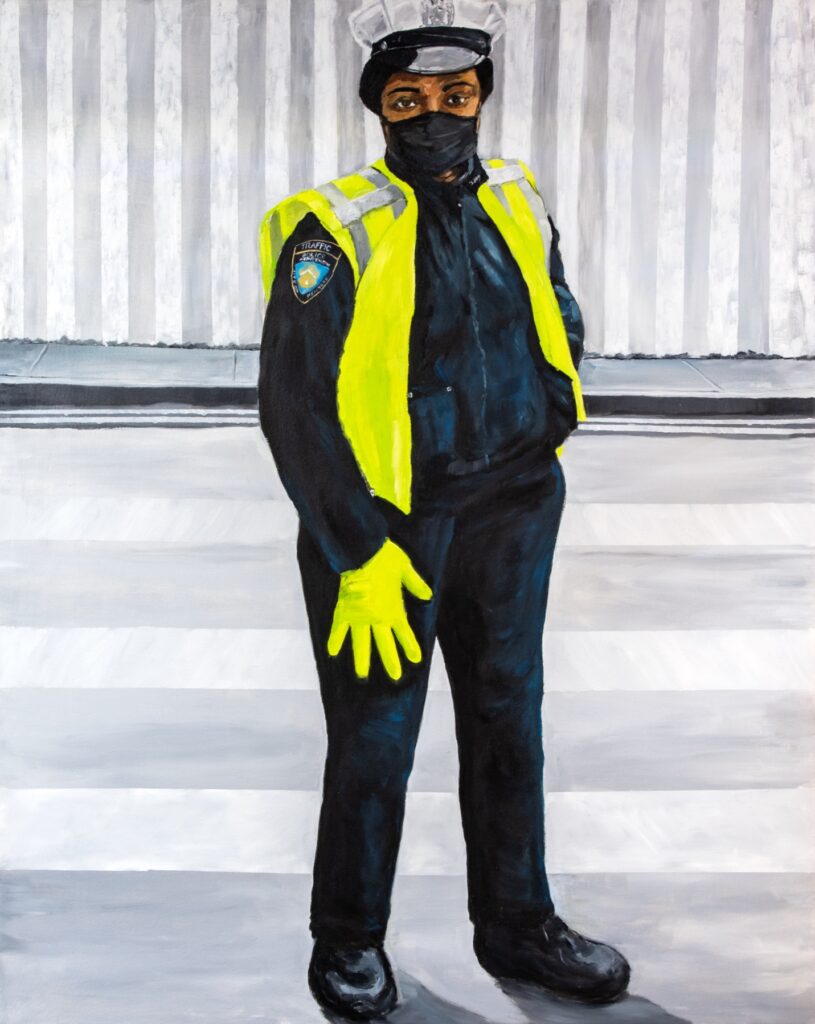

“That cop was outside of Yankee Stadium, kind of dancing and directing traffic when I walked by,†Charles says, referring to “untitled,†a newer work that’s hanging in her studio. “I came back and said, Can I take your picture? And she stopped and posed like this. I loved the contrast of her energy with this dark blue outfit and all the gray around her. To me, that says something about women in general. She’s existing, she’s making her own life in this dull background.â€

“Juneteenth†hangs next to it, a portrait of a jubilant young woman with a broad smile and oversized white sunglasses. She wears a tank top with vertical bands of green, black, yellow, and red, along with short shorts in a diagonal checkerboard print; a background of diagonal black and white stripes creates a graphic cacophony, a joyous riot of pattern.

(“I like mixing realism in the subjects with graphics in the background,†Charles says. “It’s almost as if I’m mixing both cultures, the African and the American.â€) The woman’s head is turned slightly to the side and her hands appear poised to snap to a musical beat. Her bare arms and legs are christened with a golden glow that seems to emanate from within, calling to mind Thomas Merton’s epiphany at Fourth and Walnut Streets in Louisville: There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun. … If only they could all see themselves as they really are.

XII.

“Okay, this is going to sound totally nerdy,†Charles says with a laugh and leans forward. “I learned about this thing called fractal mathematics. And it’s embedded in so many African cultures: you see the repetition of symbols and forms and shapes over and over again.â€

A writer, sitting alone at her desk, amid notes and photos, trying to build a portrait of a painter.

A painter, sitting alone in her studio, amid sketches and photos, trying to build a portrait of a woman.

A fractal. A never-ending pattern. An ongoing feedback loop.

XIII.

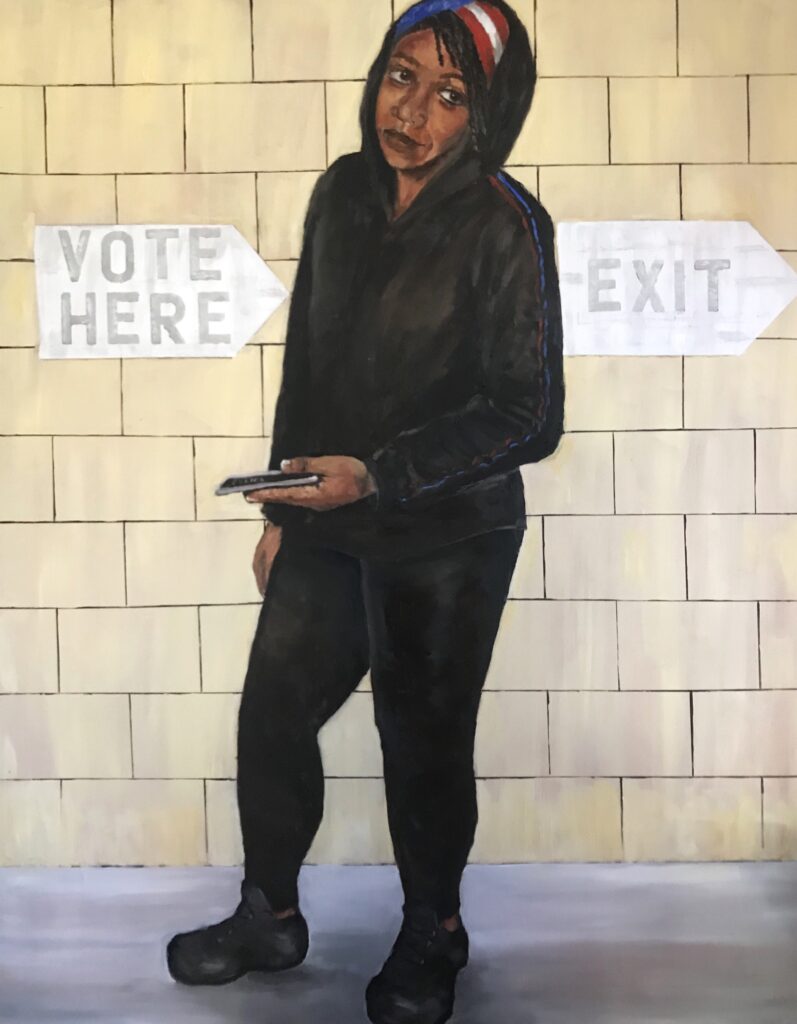

Among Charles’ recent works, there is one that haunts me: In “Her Vote,†a Black woman wears black sneakers and leggings, a black hoodie pulled over her braided hair; a red, white, and blue headwrap peeks out from under it. She takes a contrapposto stance that reflects a contemporary ennui or, perhaps, resignation: her face registers a mild annoyance at whatever unseen interruption has briefly torn her gaze away from the smartphone in her hand. Behind her, arrow-shaped signs on a tiled wall direct visitors to “VOTE HERE†and “EXIT.â€

In portraying the banality of modern voting in the U.S., Charles captures all the tension of the present moment – both the triumph that a Black woman can participate in a domain that was once the exclusive province of propertied white men – as well as a wariness about the future of this very democracy, an unease regarding its more violent and racist members. None of that emotion is present in her subject’s face: she seems bored more than anything. Yet Charles makes me keep looking.

Curiously, it is this smartphone in the woman’s hand that has curtailed so much of our capacity to wonder at other individuals: in our Pavlovian ritual of tapping it the instant we find ourselves waiting – in a restaurant, on a plane, in a voting line – we lose a curiosity about the strangers we encounter and, with that, our ability to imagine lives other than our own. Who is this woman in street clothes, waiting her turn to vote? How does she feel about the election, about her place in this country?

More than just exalting Black women, Charles is pursuing an emotional depth that is as much about the relationship with the viewer. She is asking us to invest the time in looking at this painting so that we might discover a point of connection. Aren’t we all feeling a bit uncertain these days, can’t we all empathize with this woman’s apathy at a time when it feels precarious to hold too much hope for the future? We don’t learn the name of the woman portrayed because Charles is aiming to spark a different kind of recognition – to see in this person, this other, a boredom or a joy or a sadness that we ourselves have felt. In other words, to see something of ourselves.

Top image: Sandra Charles, “Stephanie! (2022),” oil on canvas, 2018, 48″ x 60″. A Black woman wearing a colorful green dress and tall brown boots stands in front of a gray stone wall. She smiles at the viewer with one hand raise halfway. Image courtesy of the artist.