I have known and admired Carlos’ work for a long time. When I recently visited the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago (MOCP), I was reminded of Carlos’ exhibition there a number of years ago. I felt an interview with him would be a wonderful tie-in with my recent review of the MOCP, American Epidemic: Guns in the United States. I spoke with Carlos in late February 2022.

I knew Carlos from my days at Columbia College, or at least knew of him. I remember him as a photojournalism student. Back in the day, when all of the photo departments were pretty much separated and categorized. Photojournalism, commercial, and a bit of documentary thrown into the world of art there.

A photo editor said to me once, “we tend to like to put photographers in categories in our Rolodex [a Rolodex is a rotating file device used to store business contact information for those of you too young to remember] to fit our needs.” While the days of the Rolodex might be gone, pigeonholing of photographers is not.

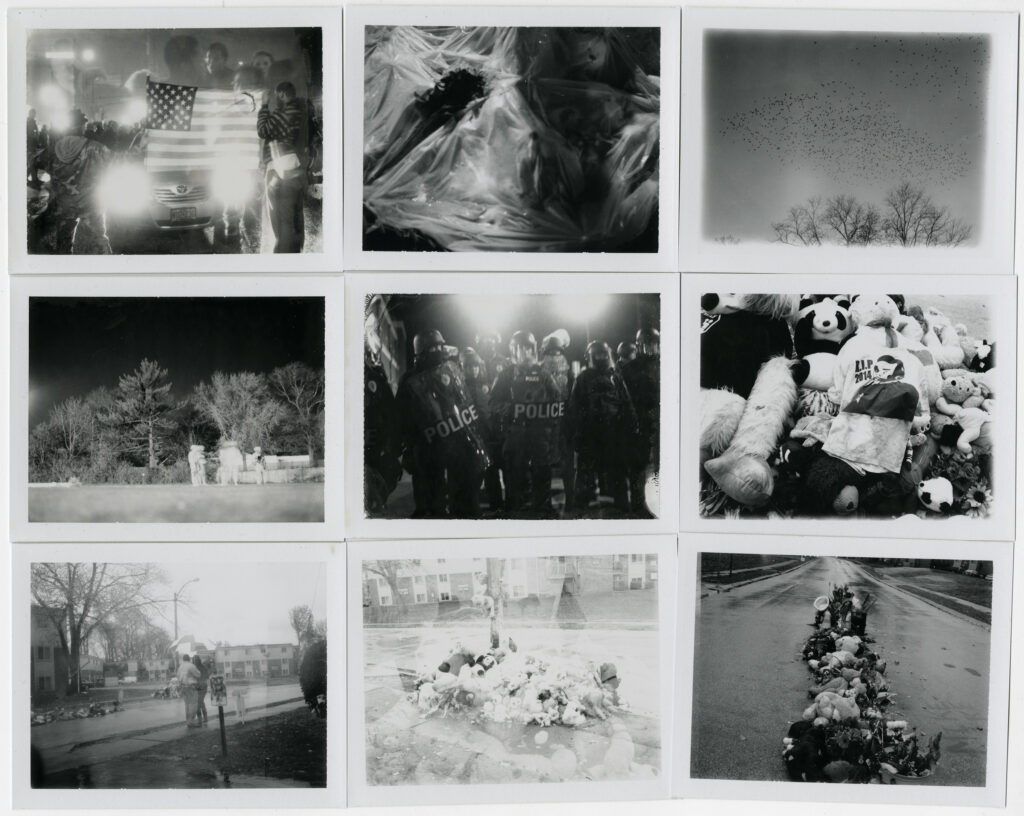

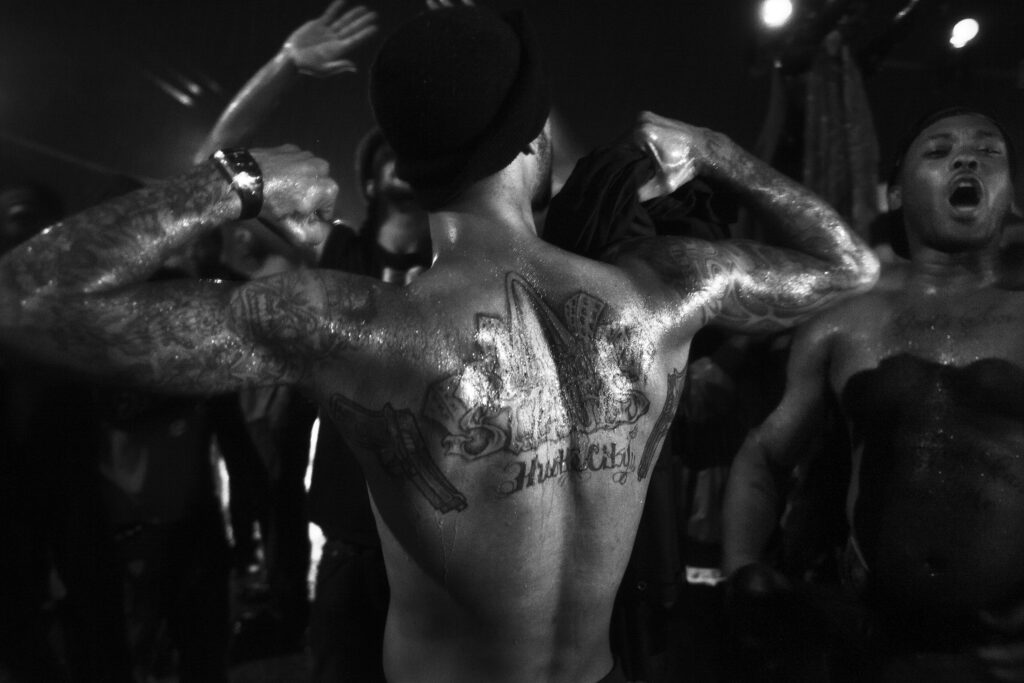

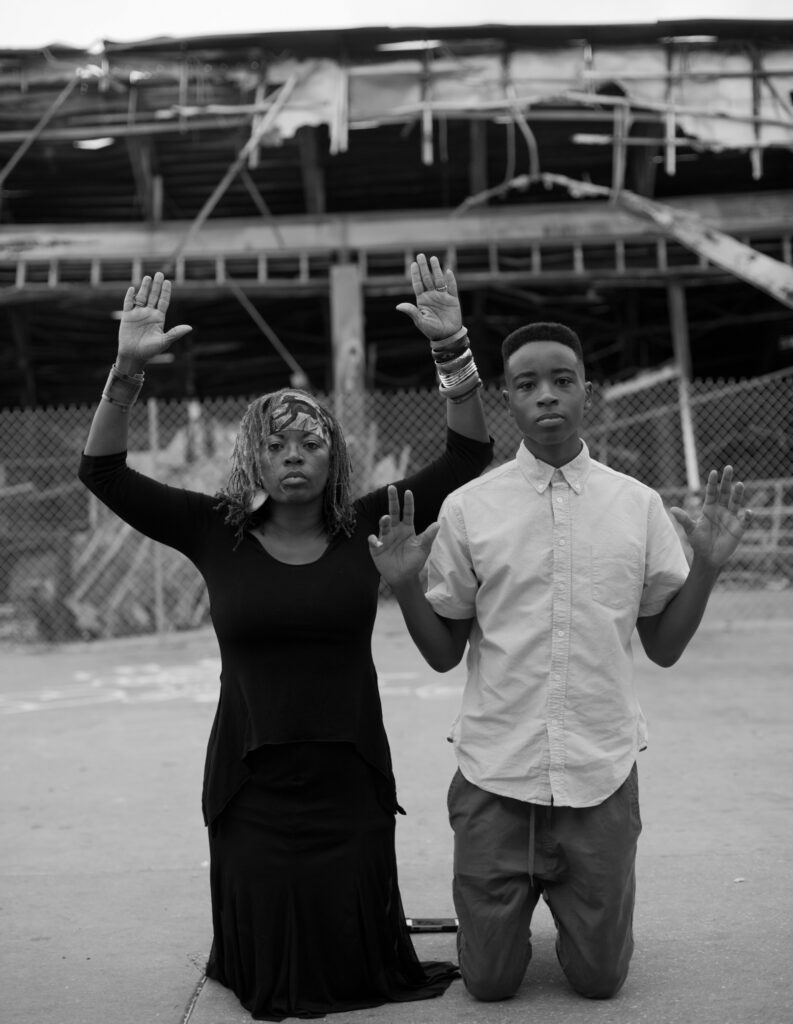

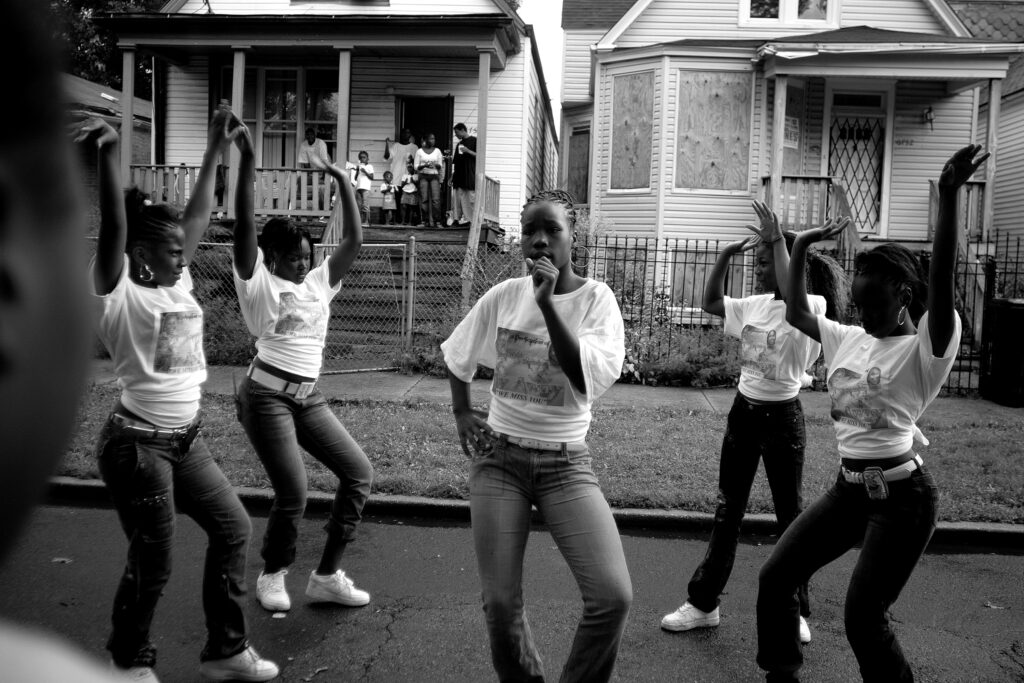

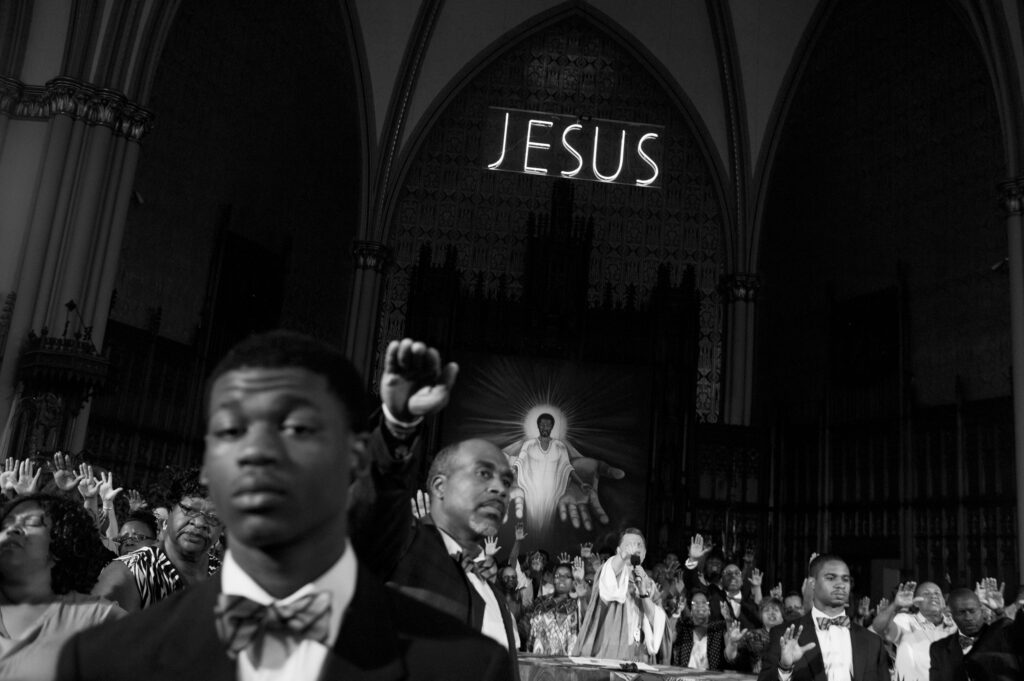

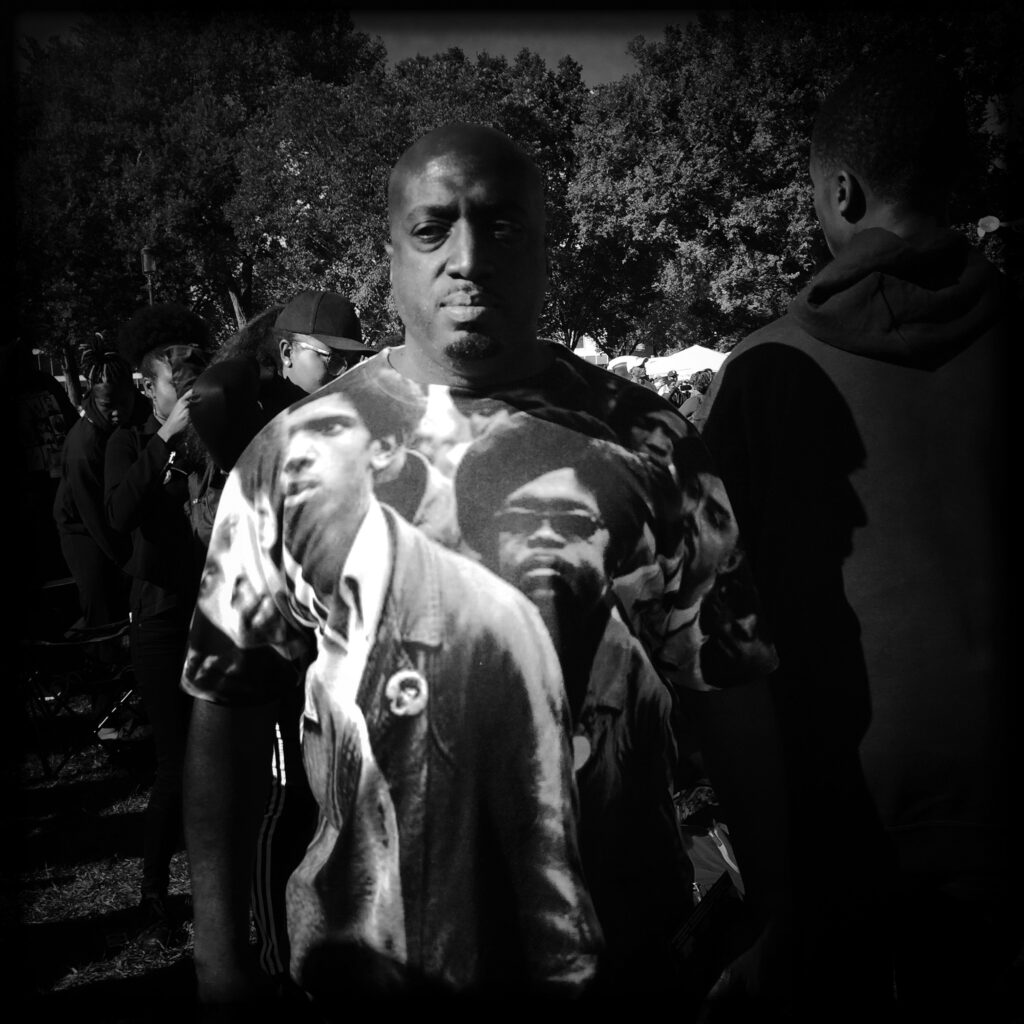

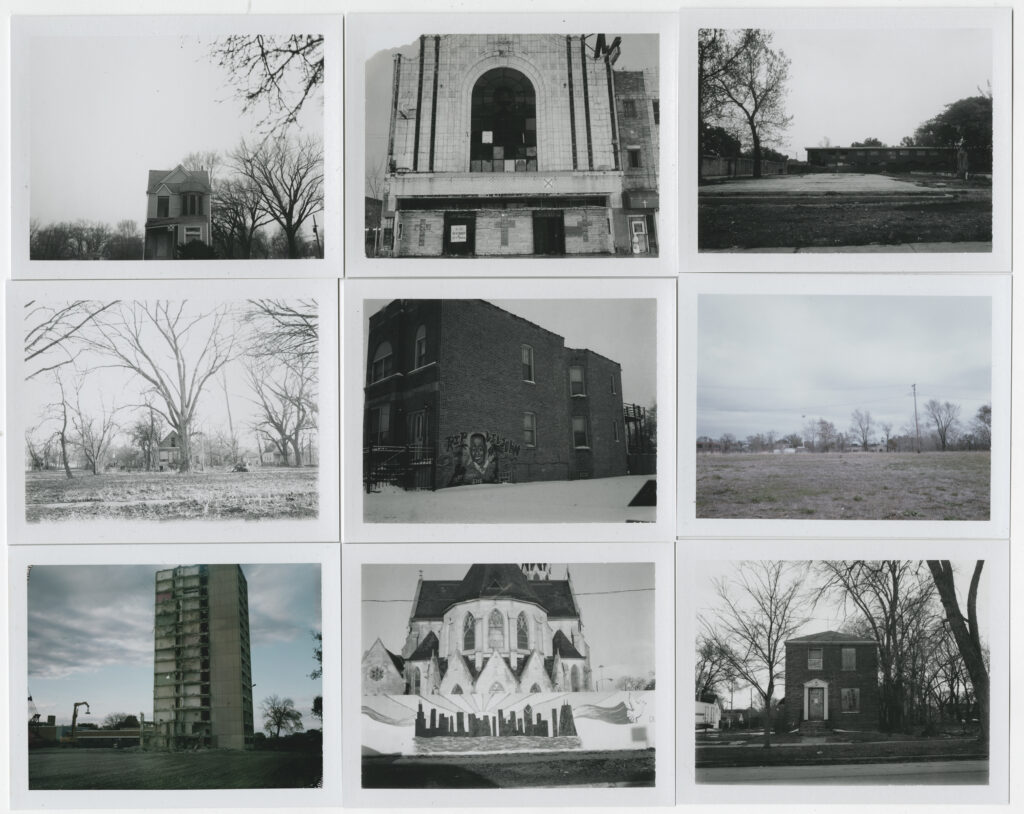

Carlos is an award-winning photographer using still photography, films, and video. He is well known for his years of work capturing the stories of gun violence, and sharing stories of heartbreak, hope, and survival.

Sarah Hoskins: I remember you as one of the photojournalism students at Columbia.

Carlos Javier Ortiz: I was exploring; I was taking an art class then and had my first experiences with documentary photography and/or art. I never did understand what was considered art photography or photography in art.

There was a point where it got separated, I mean, Gordon Parks was considered a photojournalist, and now he is regarded as an artist.

SH: You recently received a Guggenheim Fellowship for Film-Video. Was there a conscious switch from still images?

CJO: It’s artistry. It wasn’t self-appointed; it was something that came to me by other filmmakers. I started looking at it and following it.

SH: Was there anyone specific who inspired you to be a filmmaker?

CJO: Not really; I think I have been inspired by the craft of filmmaking, the idea of it, and the freedom it brings, but not one person in particular. Obviously, there are directors that you grow up with, and you’re like, WOW.

SH: These days are you making more films than still images?

CJO: No, I am not, I am doing it all. Films, still images, I am not molded in either way. Motion film is just an additive of what they call still photography; it’s just one still frame moving at 24 frames per second.

SH: Do you clip with film? When you are reviewing it or editing it, do you think hey, this would make a good still image? Or does the film stay a film?

CJO: Yea, I am working on it. I am playing around with that process. It’s a really good process.

SH: How did We All We Got change your life? There had to be a lot of trauma to make it?

CJO: After that, there was a while that I just, it wasn’t that I couldn’t, it was just that I needed my own time to reflect. I was back and forth between Chicago and California. Living in between these two spaces.

After George Floyd and that summer happened, everyone was like, were you out there working on it? Because of what I did before, I think a lot of people really pointed out and thought that I foresaw the future, and it was interesting.

No, I wasn’t out there. I was home taking care of my child. Something told me that, hey, this is what you need to be doing. I needed to take care of my child; it was my time to take care of him. It was his mother and I and our whole family taking care of him. It wasn’t just me by myself; it was our whole family.

SH: You’re a fairly new father. Has fatherhood changed your work? Do you see differently?

CJO: Yes, absolutely, it’s changed my work in the way it’s come full circle understanding what parents go through in their everyday life. It’s not like you didn’t have an understanding. It’s just different.

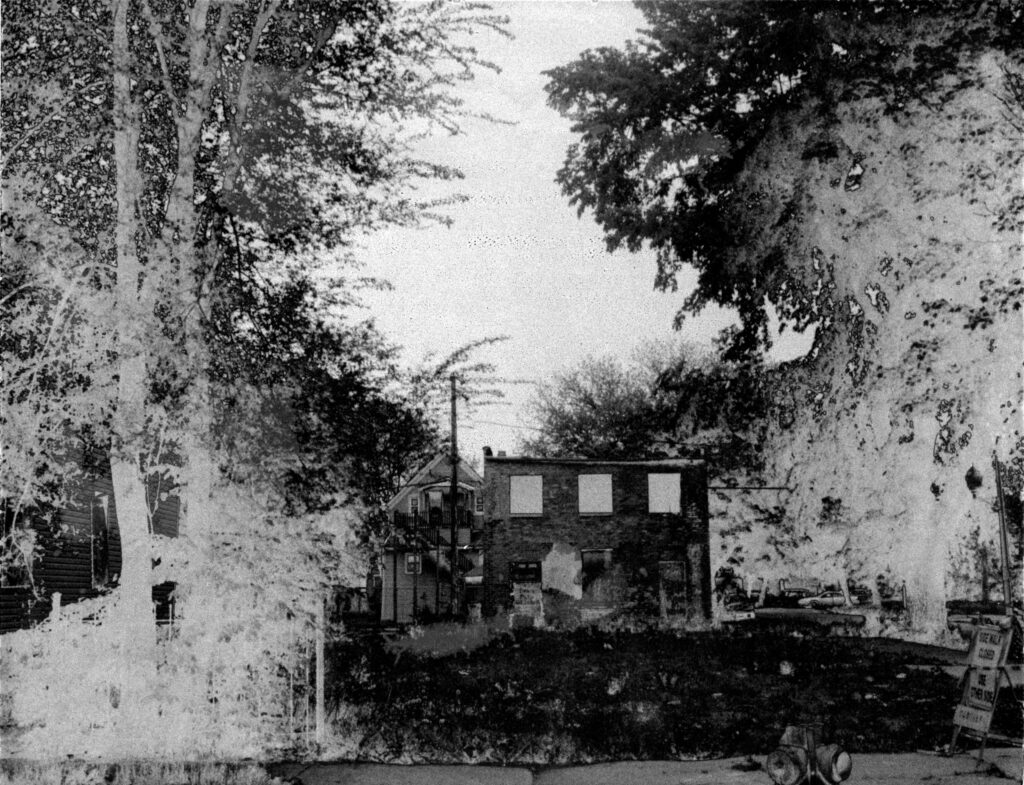

I mean, the work I make is all for him, it’s obviously for the public, but really all for him, it is for his legacy, his vision, someday how he is hopefully going to explore life or how he is going to see something or go through it. He was sick, and he was in the hospital for like a month. And during that time at night, I would stay with him overnight and if it wasn’t super cold, I would take walks at the lake, and I would just shoot with this 8mm film camera. I would just shoot stuff that reminded me of him as he dreamed it’s like a diary for him. It’s a big poem, and it’s something I have to keep working on, and it’s all silent. I don’t think we escape this life without trauma. How do we teach ourselves how to cope with that trauma? How do we teach ourselves to fight through it?

SH: Did receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship change you?

CJO: Oh yea, absolutely. I think the Guggenheim offered an opportunity to think differently as an artist and to be able to think about creating a production company and a place to put ideas into besides my name. It created a space for community for me, how to engage my process as an artist. I was at the Tribeca film festival, and I was sitting in a friend’s kitchen in Crown Heights. I started thinking about Brown Planet Productions, creating a production company, a place to name my work and not just my name; it flushed out my thoughts and creative thinking. Not just a photographer but everything else that came with it, you know how to influence the commercial world through art and visualization of how people see, how people of color see within that world. The commercial work was great; obviously, I worked on my film projects, too, but it really offered me a chance to start the idea of a production company.

I think that is the most important part, the idea, influencing the idea into your art practice. The company could fail or succeed, right? That is just about luck and work and obviously skills, but the idea has to live in order for it to be successful.

I think the Guggenheim offered me a place to just open up, you know? And be able to breathe and think and influence and the prestige you know…. your life might not change, but it’s a place to open up.

SH: What can we expect next?

CJO: Hmm, good question. I’m working on some things I don’t want to talk about now.

We will just have to wait and watch and look at these moments for now and wonder and look forward to what will be next.

* * *

Top image: Carlos Javier Ortiz, The Bud Billiken parade, 2012. A black and white photo of a crowd of people in uniform throwing color guard rifles in the air. Image courtesy of the artist.

UnderMain: On the Road sends writers out of Kentucky to explore the visual arts in cities of the Midwest and near South. This program is generously supported by the Great Meadows Foundation.