Some artists zoom in and focus on the small details of whatever they’re depicting or evoking: a place or person, an object, a thought, a feeling. Think of Matisse sticking close to home, cataloging the contents of his red studio: the paintings on the wall, the chairs for viewing them, the table, the wineglass. Others take a decidedly more macro approach, zooming out and up for the crow’s-eye view – Breughel’s hellscapes, Picasso surveying the destruction of Guernica.

Matthew Ritchie, the multimedia artist whose sprawling, insistently brainy, wildly ambitious work is gathered in A Garden in the Flood at the Frist Art Museum in Nashville through March 5, is largely in the second category. In mostly abstract paintings, drawings, sculpture, video, and other mixed-media work throughout this vast, thematically overstuffed survey of his output since the year 2000, Ritchie leaves that crow in the dust, zooming out to what feels like deep space. In the paintings in particular, it’s often as if we’re being shown our world from some distant galaxy – perhaps with the help of something like the Webb Space Telescope, whose recently reported images of the universe as a collection of swirling, colorful miasmas would seem like source materials for Ritchie if they hadn’t come out just months ago.

Addressing his topics and his viewers from a perspective that incorporates ideas from science, history, philosophy, and other disciplines, Ritchie seems to be inviting us to consider nothing less than the past, present, and future of the universe, the place of humankind within it, and how we’ve conceived our relation to the world over the past few millennia. The exhibition’s title, evoking (among other things) the Garden of Eden and the destructive flood that follows it in Genesis, suggests an artist’s vision of something like cosmic destiny, envisioned as unfolding in a repeating cycle of creation, destruction, and renewal. Not that many of the artworks, despite their occasionally apocalyptic tone in relation to climate change, war, and the unpredictable consequences of technology, feel particularly Biblical; their most frequently consulted intellectual inspirations are theoretical physics, astronomy, and the history of thought.

Examples include “M Theory†(2000), in which the artist offers a sort of dramatization of string theory as a wriggling, barely stitched-together mass of matter and energy as envisioned by numerous, constantly surveilling human eyes. (Bulbous or saucer-like eyeballs repeatedly function in Ritchie’s work in ways similar to their ubiquitous appearances in the output of the late American sculptor Lee Bontecou, who feels like a guiding spirit here.) In “The Eighth Sea†(2002), more eyes watch as a human body seems to return to, and be reabsorbed by, the oceanic ooze it crawled out of. All of the scientific study and theorizing that these paintings draw from, Ritchie seems to be reminding us, are products of human consciousness, and therefore say as much or more about human thought – its relentlessness and potential, its limitations and fallibility – than the universe itself.

Those eyes, so often looking up at the stars here, are also capable of focusing on subjects closer to home. In “No Sign of the World†(2004), the monumental (99†x 154â€) painting that gets pride of place in the first of four large galleries that contain this show on the Frist’s second floor, the artist, perhaps referring to the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, conjures the horror of terrorism with twisted plumes of smoke, clusters of eyeballs suggestive of exploding human bodies, and vaporous figures that might be souls drifting upward. It’s a starkly grief-stricken and powerful work, reminiscent of Anselm Kiefer as his eeriest and bleakest but with a softer, sadder, more lyrical palette. It’s a reminder that for all of Ritchie’s cerebral qualities – and the way he often seems more interested in thought than feeling, at least as subject matter – he’s first and foremost a painter of considerable expressive depth, capable of engaging his viewers emotionally as well as intellectually.

There are even, in two of the most recent works in the show, some lighter touches of what I take to be humor. “Harbinger†and “Discriminator,†both painted in 2022 with the help of artificial intelligence programs called generative adversarial networks (which produce what a wall text calls “unrecognizable, yet strangely familiar images from which the paintings are developedâ€), strike me as ominous in a way that’s typical of Ritchie but also atypically comic, even endearing. The slightly cartoonish figure in “Harbinger,†holding its head in a way that suggests it’s warning us about some oncoming apocalypse (take your pick), does so in the exaggerated manner of the Toons in Warner Bros. shorts, not to mention Edvard Munch’s “The Scream†[1893], which I’ve always felt richly deserving of its million parodies. “Discriminator,†whose mass of intertwined, googly-eyed figures reminds me of some of Picasso’s folklore-inspired art, I also couldn’t help smiling at. It was strange in this otherwise dead serious exhibition to be ambushed by a few chuckles, but there it was. It also made me regard Ritchie’s fairly ostentatious erudition in this show – far from wearing his learning lightly, he often seems intent on rubbing our noses in just how much homework he’s done – as considerably less off-putting than it might have otherwise. If this artist is a genius, as he may well be, he doesn’t always take himself all that seriously, which becomes him.

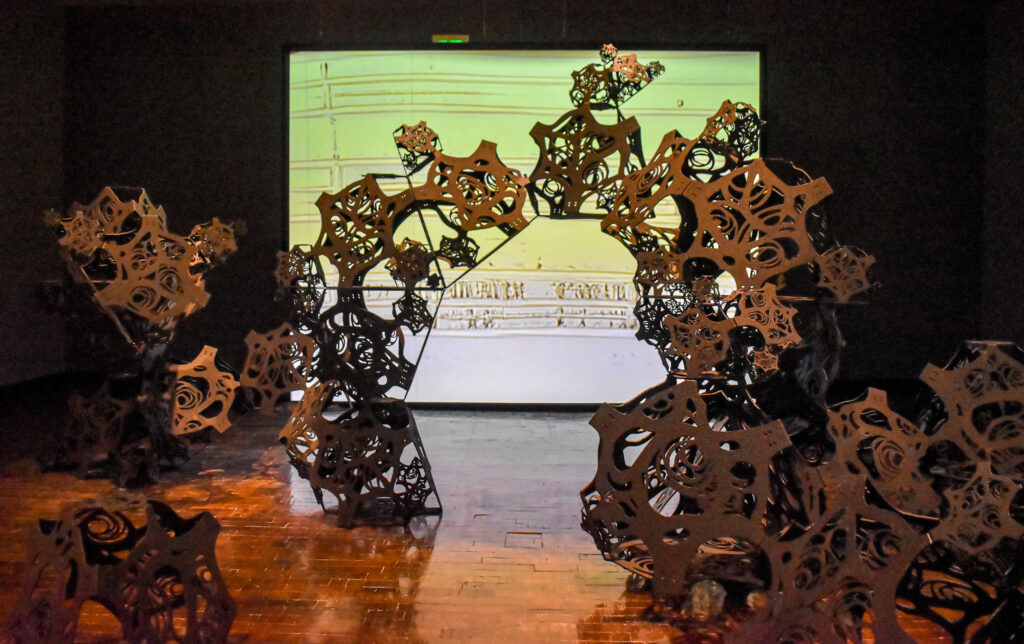

That said, the remaining three galleries of the show, featuring Ritchie’s conceptual work in sculpture, video, light panels, and other mediums, lack the individual and cumulative impacts of the paintings in the first gallery. A walk through these rooms yields mixed results, starting with “The Dawn Line (Weather Eye Variant†(2022), a boxy sculpture made of aluminum structural units with the help of a team of physicists, architects, and engineers. It’s intended as a sort of 3-D model of the universe, but being neither a physicist, architect, or engineer myself, I found it handsome but rather a cipher. (It’s easy throughout this often head-scratching show to feel embarrassed by one’s own ignorance of these large, complex topics and technologies, and “The Dawn Line†had me smarting worst of all from my lack of high-tech savvy or a Ph.D. in cosmology.) Better and more accessible, in the next gallery, is “The Arguments,†an installation of several of the artist’s videos from over the years. They’re mysterious and slow – hypnotically or tediously so, depending on your point of view – and play in various ways with the ideas implicit in the exhibit’s umbrella title, A Garden in the Flood. (The soundscape is blessed and made at times more explicitly religious, even Judeo-Christian, by the glorious musical contributions of Nashville’s Fisk Jubilee Singers, the legendary choral group justly celebrated for its intensely moving renditions of American Negro Spirituals.)

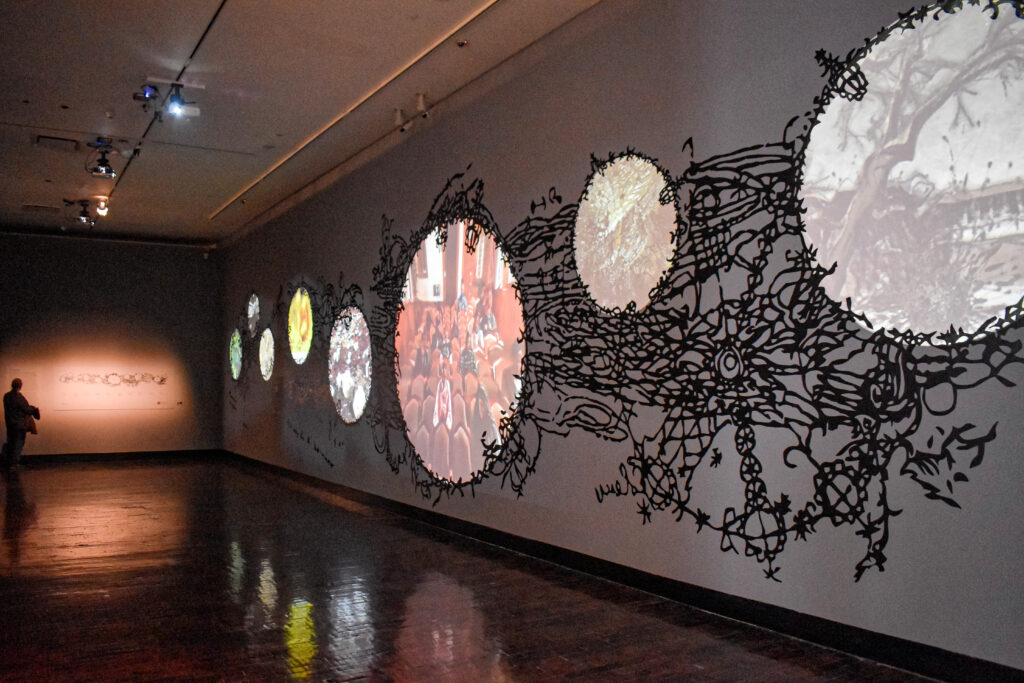

In the fourth and final gallery, the viewer is confronted with a head-spinning grab-bag of works using a variety of mediums and approaches (including video, moveable LED panels, and drawings), most of them dealing with the history of thought and the ways it’s been depicted and diagrammed by artists through the centuries. The elegant scrawl on the walls of the gallery evokes the notebooks of creative minds from Leonardo da Vinci to Renzo Piano, and I think we’re meant to include Ritchie himself on that continuum. I don’t dispute it, although I confess the almost frenzied busyness of this last installation left me more tired than exhilarated. And I was drawn less to the bells and whistles in the room (which included a video of modern dancers interacting with an earlier version of the installation) than to what struck me as the possible Rosebud of the overall exhibit, tucked inside a comparatively low-tech series of drawings on Mylar called “Five of a Kind†(2003). Although the drawings engage enormous ideas about the fluidity and randomness of the universe and the eternally disruptive forces at work within it, Ritchie captures in a single vignette, rendered with the simplicity of a child, the essence of this entire show. It’s a tree with deep roots and, in the abundance of its branches, a harvest of apples that form the eyes of human skulls. We recognize this tree of knowledge and the people dancing in and beneath it, setting into motion the beginning and the end and the beginning.

Top image: Installation view of Matthew Ritchie: “A Garden in the Flood” at the Frist Art Museum. A person sits on a bench in a gallery looking at a large yellow painting “No Sign of the World” (2004) by Matthew Ritchie. Photo by Kevin Nance.

UnderMain: On the Road sends writers out of Kentucky to explore the visual arts in cities of the Midwest and near South. This program is generously supported by the Great Meadows Foundation.