Art may be uniquely positioned to contain all manner of ambiguities and complexities, but there’s also something to be said for its capacity to crystallize and summarize. That’s what happens, over and over again, in The Future Is Female, the cogent and impressively large traveling exhibit of feminist art that’s been making the rounds of 21c Museum Hotels in recent years and is now resident at the chain’s Nashville location, with recent additions by 21c’s chief curator, Alice Gray Stites, through June.

Displayed on three floors here, many of the dozens of artworks – almost all of which address the history, suffering, evolution, self-exploration, and self-assertion of women, individually and collectively – have the crisp, clarifying effect of instant iconography. One look, typically, and you get what’s being said. And something is always being said, more or less clearly, and why not? Art doesn’t always need to whisper or mumble. Sometimes – and the current historical moment is self-evidently one of those times – it’s necessary to just say it, name it, own it.

And so it is that “Champ” (2016), Zoë Buckman’s lightning-bolt artwork – featuring a glowing neon glass model of the female reproductive system with a pair of boxing gloves standing in for ovaries – sums up the long, bitter, ongoing battle over abortion rights. Given the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade by the U.S. Supreme Court, Buckman’s title feels less confident than before but all the more relevant; this particular boxing match is far from over and fiercer than ever.

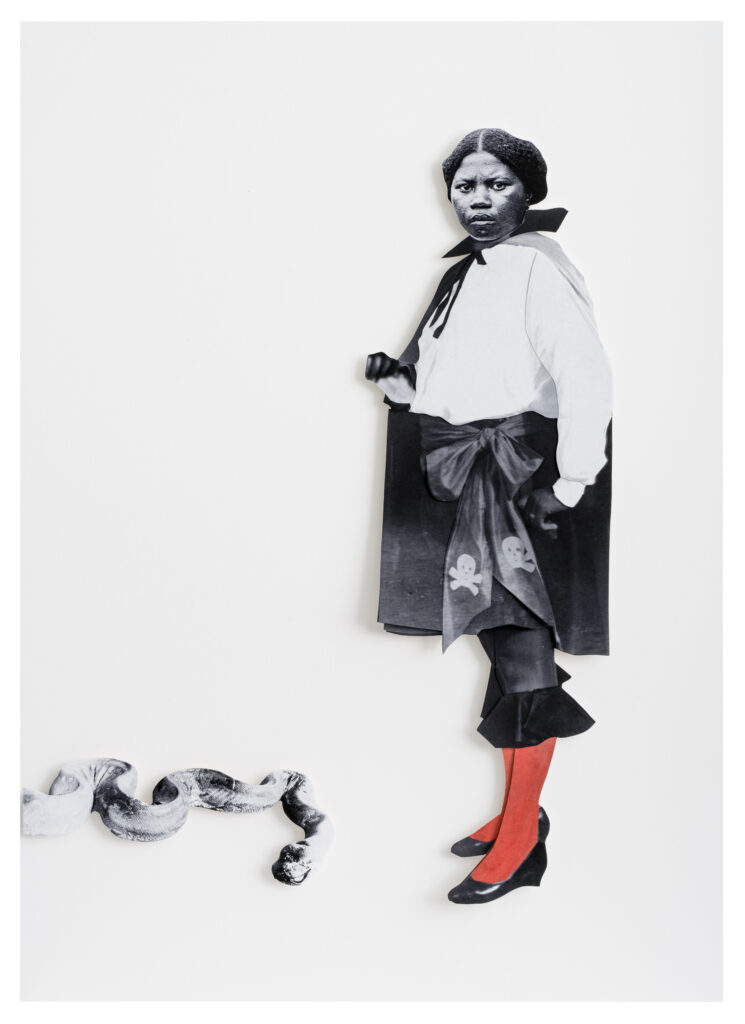

We see a similar, bulls-eye succinctness in several other works here, including in the political shorthand of Michele Pred’s “Reflections” (2015), a series of labeled hand mirrors in which viewers are invited to see themselves as “equal,” “feminist,” and “powerful”; and in Frida Orupabo’s collage “Woman With a Gun” (2021), in which a black woman menaced by a snake at her feet (and also, perhaps, by whomever she’s glaring at, defiantly, outside the frame) appears more than ready to defend herself.

The show is particularly stacked with arresting photography, with Carrie Mae Weems, Mickalene Thomas, Catherine Opie, Nandipla Mntambo, and others making strong contributions. In Weems’s “A Single’s Waltz in Time” (2003), the photographer, a black woman, dances in what appears to be the elegant drawing room of a Southern plantation house, reclaiming a space built from the labor of enslaved human beings as a place to be free. I was struck by Mntambo’s subtly lit, richly ambiguous series “… everything carries a shadow” (2013), in which a woman and a man, both nude, entwine their bodies in various configurations that suggest love, sex, conflict, and sometimes all three.

And if the future is female, it’s also transgender, non-binary, and/or gender fluid, as suggested in several works here, including Opie’s “Jesse” (1995), a photograph of a child of still developing and as yet indeterminate gender identity, and “Two Year Hymn” (2019), Hannah McBroom’s striking collection of painted self-portraits reflecting her transition from her originally assigned male gender to that of womanhood with the help of hormone therapy. What stands out most in McBroom’s series is the fact that the portraits don’t appear to be ordered in chronological sequence, suggesting an imprecise, nonlinear progression from one gender to another. Indeed, the shift from one to the other is so subtle that the viewer is struck by how similar the earliest and latest portraits are to one another, not how different. The essential self is constant. The eyes are the same.

Top image: Zoë Buckman, Champ, 2016. Neon, glass, leather. A glowing neon glass model of the female reproductive system with a pair of boxing gloves standing in for ovaries. Courtesy of 21c Museum Hotel, Nashville.

UnderMain: On the Road sends writers out of Kentucky to explore the visual arts in cities of the Midwest and near South. This program is generously supported by the Great Meadows Foundation.