My recent visit to take in Watershed, an expansive exhibit at the University of Michigan Museum of Art in Ann Arbor, was an immersion in the beauty, fragility, and pained history of the largest concentration of fresh water in the world. Curator Jennifer Friess brought together works from fifteen contemporary artists to explore threats and challenges to the Great Lakes watershed. Their works spoke to both meanings of the word: the environmental geography that drains to a particular body of water and the cultural experience that marks a crucial turning point.

The space was anchored by three large pieces on the perimeter walls, which provided an overview of the show’s interwoven themes.

Wall 1

Canadian Anishinaabe/Ojibwe artist Bonnie Devine painted a mural directly on the gallery wall during the first two weeks of the exhibit. The centerpiece of The Gift is a black map of the lakes themselves. A broad road crosses the map, reminding me of the song lyric, “they paved paradise and put up a parking lot.†But Devine is drawing attention beyond the environmental ramifications of the “development†of the region to expound on colonial expansion, when Europeans violently laid claim to these lands already home to her people.

A block of text on the right side of the lakes gives context to the name of the work. It tells part of the origin story of the University of Michigan, home of the museum. The Three Fires Confederacy was persuaded to give the state land in 1816 with the promise that their children would have greater access to higher education and be able to enroll in the institution. When the Confederacy sued the University in 1971 for a breach of that promise, the court ruled for the school, stating the land grant was “a gift.â€

Wall 2

Cai Guo-Qiang’s large (about 10’ by 36’) Cuyahoga River Lightning drew visitors to the back wall. It commemorates a moment in 1969 when the Cuyahoga River was so full of industrial contaminants that it literally caught fire. Labeled as a drawing, the artist’s medium is unconventional. He traced the river’s path with gunpowder and small firecrackers, then ignited it, leaving black and brown burn marks on the canvas. Flecks of fire strayed beyond the outline of the banks, reminding me of the uncontainable nature of pollution.

An accompanying video shows archival footage of the river fire interspersed with clips of the artist creating the work. The only sounds are the cracks and snaps of the tiny creative explosions. The final scene shows Guo-Qiang walking along a clear, bubbling stream.

Fire can destroy, but it can also purify. This tragedy became a flashpoint that bolstered the emerging environmental movement and led to significant clean-up of the river itself. One of the few pieces in the exhibit that reflected a crisis that has, for the most part, been resolved, Cuyahoga River Lightning offered a spark of hope.

Wall 3

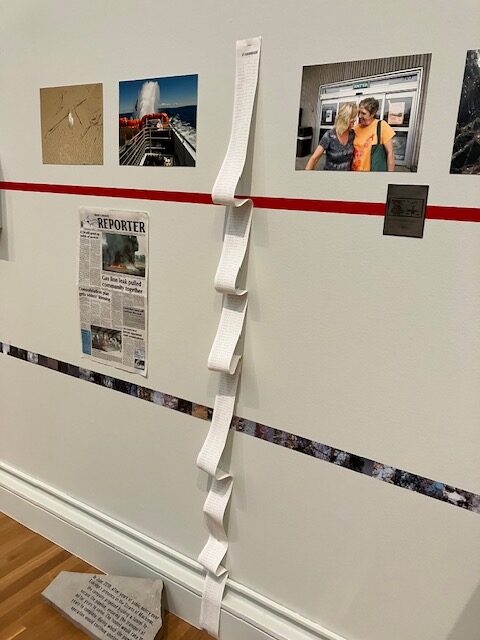

The third wall held a complex installation called, The Roar on the Other Side of Silence (Along Line 5). Really several works in one, it was comprised of pictures, an interpretive booklet, a silent video, and two different audio recordings. A thin red timeline with photos and memorabilia ran the length of the wall. Numerous artifacts from decades of history regarding Line 5, Enbridge’s seventy-year-old pipeline running under the Straits of Mackinac, stood on pedestals or were affixed to the wall.

It was only possible to wade into this piece; it had an overwhelming volume of information and images to consider. I found some of the elements particularly arresting. A long cash register receipt, pleated to fit on the wall, that cataloged numerous spills from Enbridge’s pipelines. A resin-encased packet of papers 3†thick, a company-authored Environmental Impact Statement for a possible relocation of the line in Wisconsin. A video segment showing a family building a simple sand castle on an empty beach, with the lake waters quickly disappearing into oblivion.

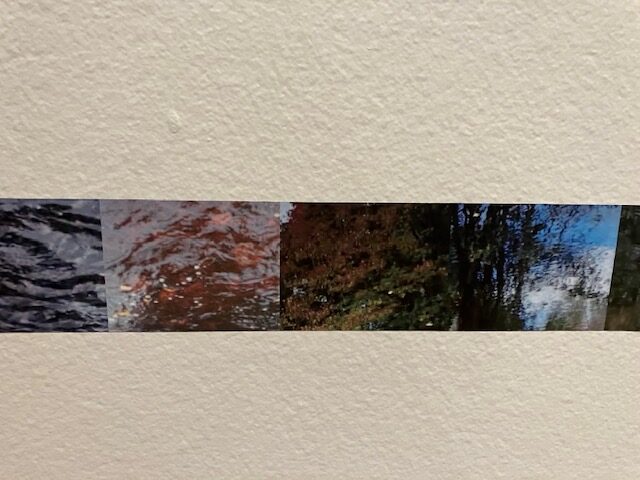

Underneath the red line ran another, more subtle, band of pictures I first viewed as a pattern rather than individual images. This piece of the work, titled Stream, documents the 186 water crossings that would be affected by a possible relocation project in Wisconsin. In 2017, the Bad River LaPointe Band of the Lake Superior Chippewa refused to renew some of the company’s easements on tribal lands. A lawsuit to evict Enbridge from their land is still in litigation.

The many elements of The Roar on the Other Side of Silence (Along Line 5) balance appreciating the landscape that holds it, celebrating the communities of resistance working along it, and facing the strong economic and political forces that built and preserve this aged infrastructure.

Other Works

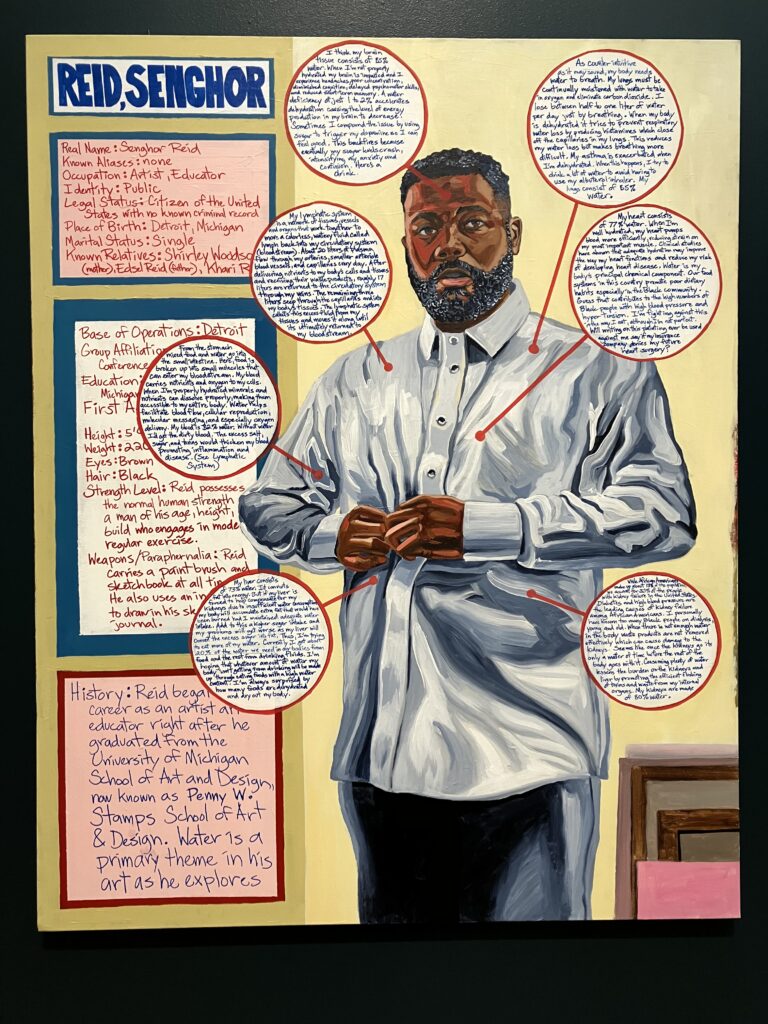

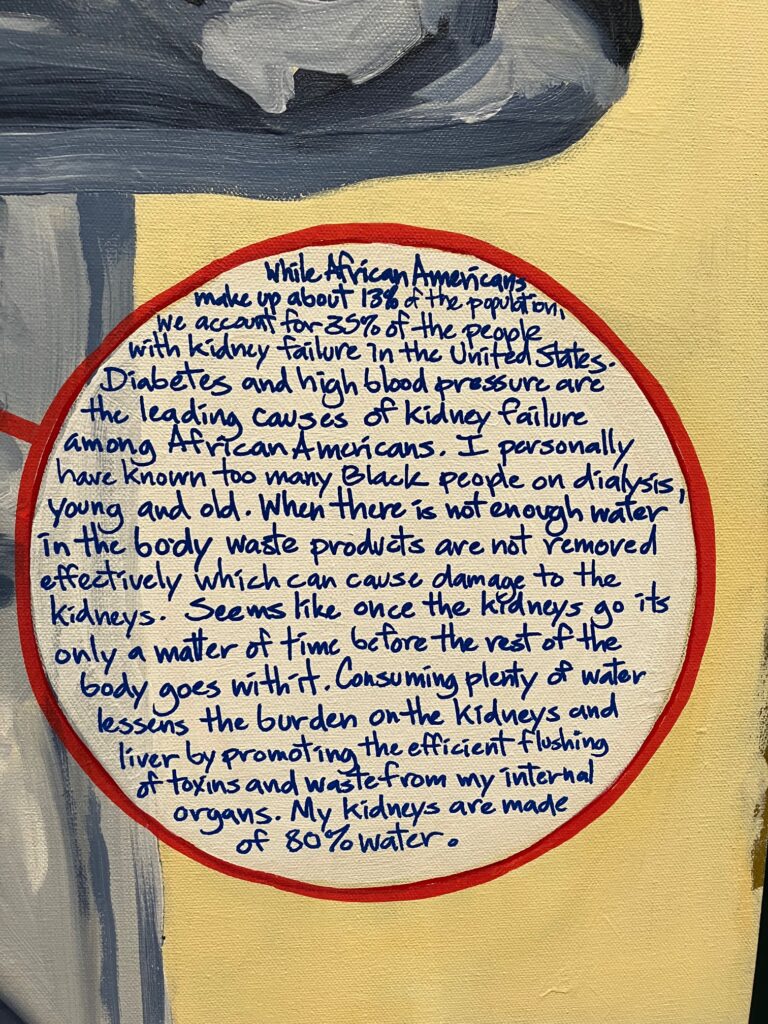

Detroit artist Senghor Reid had two self-portraits in the exhibit. Gray’s Anatomy IV imitates a Marvel Universe page detailing the special powers of a superhero; his weapon is a paintbrush. Each text bubble shares hard science emphasizing the importance of water consumption in being able to fully use his human powers. As he shares the impact of drinking – and eating – more water on his own health, he also calls attention to some of the health disparities Black Americans face.

The exhibit contained a sizable number of photographs, many of which used or represented contaminated water in the processing. In her trio of dynamic cyanotypes commissioned for Watershed, Meghann Riepenhoff hand-coated sheets of paper with a UV-sensitive cyanotype emulsion. She then stood in New York’s Genesee River and washed its polluted waters over the paper. While the toxic water creates enchanting and vivid swirling blues and grays, her method has a deep irony: one of the major polluters of the Lake Ontario watershed is Eastman Kodak, a photography company.

Beyond the artworks, other elements of the exhibit deepened the intentionality of its message. All of the gallery notes were printed in two languages, English and Anishinaabemowin. A workbook on health disparities introduced and engaged children and youth with the major themes as displayed in the art.

This was a bold, beautiful, yet draining exhibit. Intentionally developed to “demonstrate how art can contribute to and shape current dialogues on the critical problems confronting our region,†as written by Friess, it confronted viewers’ complacency in the face of environmental and cultural crises. It seems incongruous after viewing an exhibit called Watershed, but I left it with a thirst: a thirst for justice for the people, communities, and ecosystem of the Great Lakes region.

Watershed was on view at the University of Michigan Museum of Art in Ann Arbor from June 4–October 23, 2022.

Top image: Kate Levy, The Roar on the Other Side of Silence (Along Line 5), 2022, multi-media installation. An assortment of photos hangs on the wall, with two horizontal lines going across the wall: one made up of smaller photos, the other a solid red line. Additional materials can be seen on view on top of several white pedestals. Photo by Charlie Edwards.

UnderMain: On the Road sends writers out of Kentucky to explore the visual arts in cities of the Midwest and near South. This program is generously supported by the Great Meadows Foundation.