There is a vast array of art and artists and limitless ways to describe them. She is a Canadian abstract painter. They are a Midwestern queer performance artist. He is a Mexican American sculptor. But, for the sake of art history, there are definitions and there are categorizations. By her own definition, Alivia Blade is an interdisciplinary Louisville artist. Born and raised in Kentucky, she is currently based in the Louisville suburbs. Through her work, she explores Blackness in the mid-south and her Black ancestral line through Kentucky and the greater south. But does she fall into the category of a Louisville artist? That’s not so clear.

In late August, I met with Alivia to discuss her past, present, and future as an artist in Louisville. During our conversation, it was clear that even though Alivia lives about a 20-minute drive from museums and art galleries, metaphorically, she is worlds away.

My GPS led me to an affluent neighborhood just outside the city. Only two years earlier Alivia was living and working in urban Chicago, miles away from the pristine yards in the rolling hills of the Louisville suburbs. As a recent graduate of Columbia College, she was in the nascent stages of her burgeoning art career, developing her practice, connecting with art galleries, and doing the in-person networking all new artists are obliged to do. Then the pandemic struck and, like so many others, Alivia found herself moving backward in time and into her childhood home with her parents.

It was early evening on a Saturday when I arrived at Alivia’s home studio. The sun was still high and the withering Kentucky heat hadn’t abated. And when Alivia, charming but somewhat reserved, greeted me at the door I silently blessed the a/c as I walked in. The plan we agreed upon for the interview was a studio visit and dinner. That day she wore her curly hair pulled back off her face, with the edges laid meticulously; my immediate impression of her was refreshed and put together. The bright pink blush on her cheeks matched her bright pink pants. She has a serious face but a broad smile, which I didn’t notice until later because we were both masked.

Situated on the second floor of the impressive residence is Alivia’s studio. But before she led me upstairs I took in the house’s foyer and living space. It’s a beautiful home, bright and airy, decorated in a familiar Black Southern fashion; the decorations and furniture have ornate touches that embody refinement with classic country flourishes. Prominently displayed throughout the foyer were large-scale framed pictures of important family events, graduations, weddings, and anniversaries. The home seemed comfortable and welcoming. And every inch was impeccably clean.

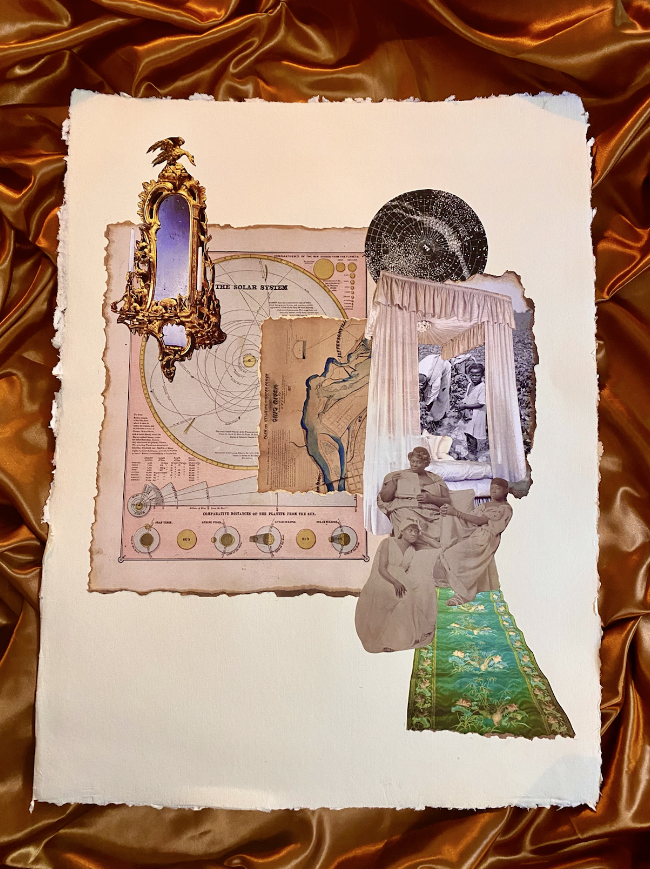

The tidily kept second-bedroom studio was arranged for the visit. Soft music played in the background; prominently displayed in one corner were her synthetic hair sculptures. These pieces piqued my initial interest in her work. On her work table were her more recent creations, collages layering vintage images of Blackness with celestial imagery and ornate home design elements. But, of all of her work, the pieces Alivia was most eager to talk about were her ancestral cards.

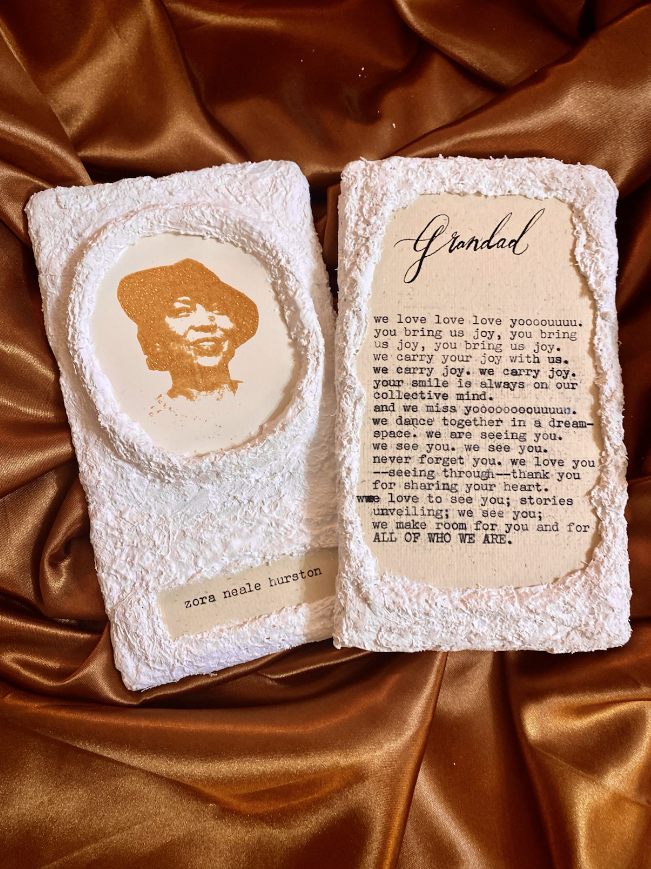

Inspired by oracle cards, each one looks like a freeform altarpiece. An individual card consists of a vintage image framed by hard-ish gold painted material with original poetry scribed on the back. The works of art can be handled; the 3D relics are meant to be handheld mementos. The pieces were borne from her desire to connect. During a particularly lonely fall in Louisville, after the death of a grandparent, Alivia was searching for, in her own words, “something that I can create that would be a reminder to me of why I’m here, why I’m alive, that I’m not just foraging a path alone, that there have been so many people who have gone before me and that I am in great company.â€

At the moment, the cards are commission only, Alivia is currently working on a deck for a friend. A completed deck will come to represent what Alivia calls, the “Cloud of Witnesses,†which are the people who have passed but still look over you in life. Using monoprinted images of ancestors she crafts each card individually. She’s been developing her process slowly throughout the project. Alivia even hopes to make them durable enough that they can be passed down through generations. But in addition to commissioned cards, she plans to make cards of people like bell hooks, Ida B. Wells, Harriet Tubman, and other communal historical Black ancestors.

Alivia’s work is deeply reflective. She’s a thinker, constantly ruminating on history and her place in the world. As we talk she contemplates life, death, generational trauma, abuse, forgiveness, depression, and loneliness, all of which she explores in her many different works. And yet, despite these complicated subjects, the beauty of her work cannot be overstated. There’s an elegant simplicity to everything she does – it comes from her design background – whether it’s her collages, ancestral cards, mini books of poetry, or lace gloves. Alivia is embracing softness and beauty with her art, works that speak directly to the experience of Black women, which she mentions emphatically more than once. That softness is in response to the hardness our ancestors had to cultivate in order to survive.

Before I met with Alivia I spent the day taking in a little Louisville culture. Louisville seems to have a preoccupation with history. Like a lot of other Midwest cities, there’s a pride in its role in early American history. But it really goes beyond that, historical themes flow through the cultural venues throughout the city. The recent KMAC Triennial was a reflection on the three years since the pandemic. But it also touched broader American history as well. Downtown a recent mural project highlights the city’s most famous history and features the likes of Muhammed Ali. Even the whiskey tour guides speak with a wistfulness of historical distilling traditions. When I think of the art in Louisville that has been the most poignant I return to The Speed Museum Promise Witness Remembrance, the memorial exhibition to Breonna Taylor. At times culturally Chicago feels so desperate to be forward-thinking and progressive, in league with New York and Los Angeles. That eagerness to be hip isn’t present in Louisville; on the contrary, arts in Louisville seem intent on their past. Not unlike Alivia’s work.

But there is a disconnect between Alivia and the greater Louisville art community. And she’s not shy about discussing it. She considers herself an outsider in the Louisville art community. Later that evening, when we sat down to dinner and I explained the scope of my Louisville project, she responded with a laugh, “Someone’s coming from out of town to go to these little shows and I don’t be going anywhere.†The more we chat the more I can tell that she’s one who moves deliberately and slowly. This applies to her art as well as to making friends. But even so, she’s an artist yearning for community. The art world can be so exclusionary. And art-making can be so isolating. Her isolation is somewhat self-imposed due in part to the emotional specificity of her art. Alivia understands her work doesn’t fit everywhere. And she doesn’t want it to. She turned down an offer to be a part of a group show because she didn’t want to be the token Black person for a white gallery. Moral opposition to being in a community with people who don’t align with her values. And that leaves her looking for spaces that “are marketed to Black folks that are queer and really interested in divesting from patriarchy, capitalism, or even the commodification of [art].†Unfortunately, they have been hard to find.

Despite her deep ambivalence toward Louisville, her work is influenced by her time in the city. In her exploration to find comfort in ancestry and history amidst the trauma and erasure. She dove deep into the archives, both personal and official. How many more Alivias are there in Louisville? Talented multidisciplinary artists who haven’t found a space for themselves in the art community. Alivia doing her own thing in isolation, slowly building and developing a practice secluded in the spare bedroom of her parent’s house. Even so, she is undeniably influenced by Louisville. Aesthetically and thematically, her work speaks to the experience of Black women in the South. And yet there is no connection between her and the arts in the community she calls home.

At dinner, I asked her about what she has derived from her time in Louisville so far. She responded after a brief pause, “To reflect a lot on my upbringing and my past. I’ve gotten the opportunity to make peace with a lot of things.†This makes sense considering her reflective nature; Alivia’s practice is moving forward by looking back on her life and history as a Black woman in the South. When we last spoke she was considering her next step. At the moment the choices are staying in Louisville or leaving for greener pastures. And if she leaves it will be a net negative for the city.

Top Image: Alivia Blade, Seasons, 2022. Collage on watercolor paper. A 2D piece lays on a burnt orange-colored fabric. The piece shows collaged photos of people with a person on a horse in front of the moon. Towards the center of the composition is an orb with a chandelier in the middle. Silverware and other objects float around the orb.

UnderMain: On the Road sends writers out of Kentucky to explore the visual arts in cities of the Midwest and near South. This program is generously supported by the Great Meadows Foundation.