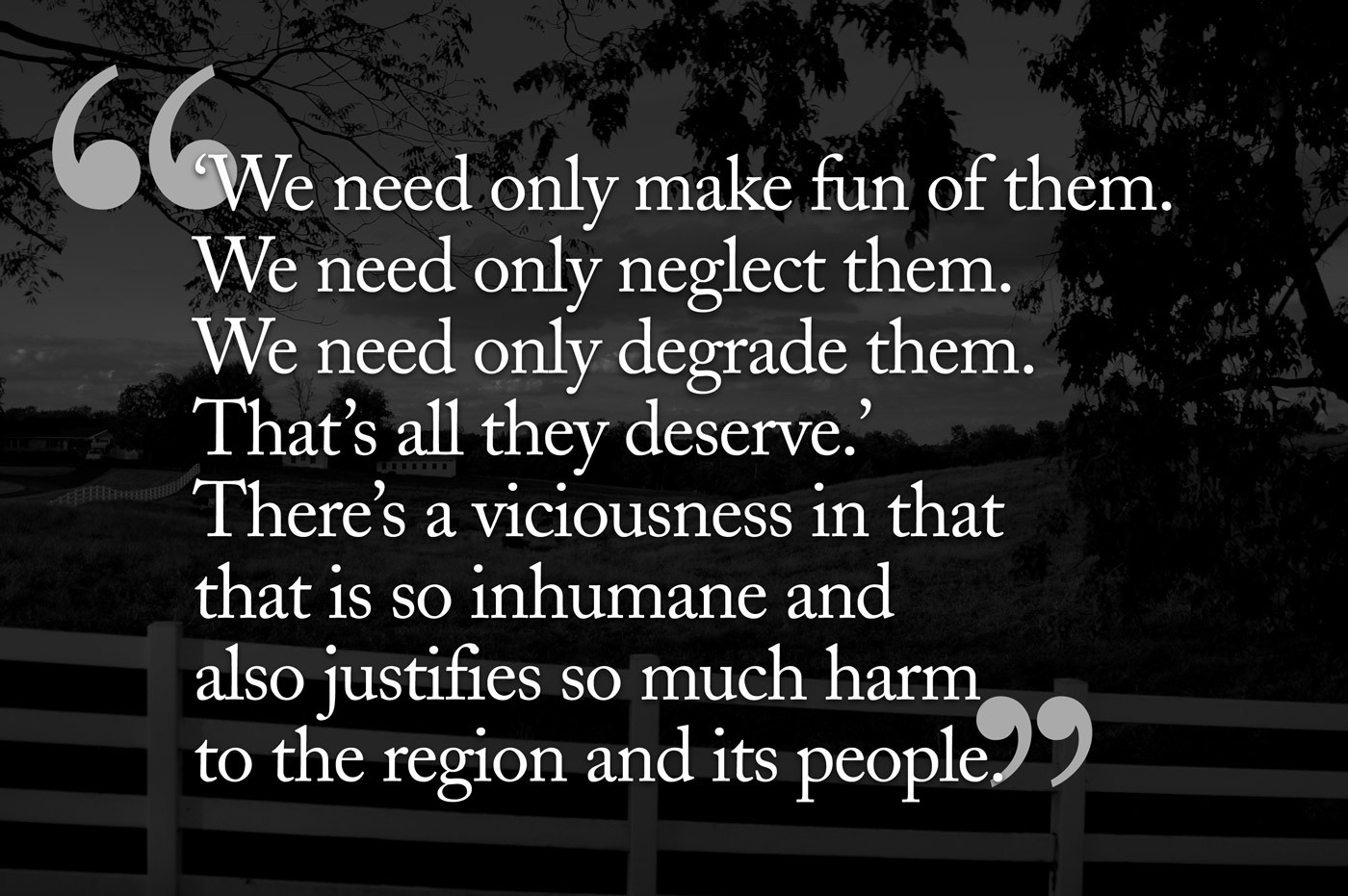

These are the words of Barbara Ellen Smith, the author of three books and many articles on Appalachia. A Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies, Department of Sociology, Virginia Tech, Dr. Smith counts herself among an impressive list of advisors for a documentary on how media has perpetuated negative, repressive and downright hurtful stereotypes of the people of the Appalachian region. It comes at a time when initiatives such as SOAR (Save Our Appalachian Region) are making intense efforts to bring opportunity, prosperity and respect to a long repressed corner of the United States.

Hollywood Hillbilly* is the work-in-progress of Ashley York and Sally Rubin. In the wake of Proper English, Y’all, Bridgett Howard’s illuminating essay on stereotyping mountain culture, UnderMain invited York and Rubin to tell us in their own words how Hollywood Hillbilly came about and what they hope to accomplish.

Where did you grow up?

Ashley York: I love that this film gives me the opportunity to tell folks that I grew up at Meathouse Holler, which is located in Kimper, Kentucky about nine miles east of Pikeville in eastern Kentucky. I lived at Kimper until I was 18 when I moved to Lexington to study journalism at the University of Kentucky.

Sally Rubin: My mom is from the mountains of East Tennessee, and much of my family lives in North Carolina, but I myself grew up in suburban Boston, lived there for the first 25 years of my life. Since then I have lived on the West Coast, first San Francisco and now Los Angeles. Along the way I also lived in France for about three years total, off and on, and I spent a year in Israel. We spent lots of time in New Hampshire growing up– my parents loved getting out of the city, and we headed to the hills as often as possible.

Where is home now?

SR: I live on the East Side of Los Angeles, in a neighborhood that is primarily Latino, mostly Salvadorean and Mexican immigrants. My home is 1000 feet up on a mountain, and feels very much like the mountains of New Hampshire and even, sometimes, Kentucky.

AY: Even though I’ve lived in Los Angeles for the past 12 years, I still refer to Kentucky as my old Kentucky home and feel quite connected to the place – perhaps even more than I did when I lived there. I speak about Kentucky almost daily because so many people I interact with ask me within minutes where I am from because of my accent. Despite my 12 years in Los Angeles living in a neighborhood just east of Hollywood called Silver Lake, I still have an accent and make an effort to hold on to it.

What are your “day jobs?”

AY: I have been on the film festival circuit with my film Tig, a documentary about the very funny and lovely Tig Notaro. We premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January and the Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival in April. I also teach digital storytelling and documentary filmmaking in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California

SR: I am full time documentary filmmaker and professor. I teach at Chapman University in Orange County, co-running the documentary film program there. I also edit documentary films and I make them, working as a producer, editor, and director.

What inspired “Hollywood Hillbilly?”

AY: It’s been a lifelong journey for me. Since I began writing as a young journalist at the University of Kentucky, I have been intrigued by stories about marginalized and vulnerable people and communities. I think that desire comes from growing up in such a homogenous place for most of my life. The tipping point for me in wanting to dive into a film that examines media representations of Appalachia and Appalachian American people came in 2013 when “Buckwild” aired on MTV. MTV describes the show as “an authentic comedic series following an outrageous group of childhood friends from the rural foothills of West Virginia who love to dodge grown-up responsibilities and always live life with the carefree motto, ‘whatever happens, happens.’” I was fully immersed in teaching and my filmmaking career when the show came out and had worked on a number of social issue documentary projects that taught me how to make socially provocative films that challenge mainstream media and offer unique points of view. “Buckwild” was so troubling for me because it was using those young people basically as non-union actors to participate in a highly produced television program (designed by corporate media executives and producers) that in my opinion perpetuated stereotypes (both positive and negative) and was exploitative of the people in the show and their community. I don’t necessarily believe the makers of that show had bad intentions but I do feel confident in saying that the show lacks critical consciousness and probably did little, if anything, to involve the community in the making of the show, outside of “casting” the young people who star in it.

SR: I’ve always wanted to make this film. I’ve been shooting in the Appalachian region since high school, filming mainly with my family at that point. During college I worked with filmmaker David Sutherland on his film about rural farm country, The Farmer’s Wife, and I became passionate about activating my politics through documentary film. I associate produced Country Boys, filmed in Prestonsburg, and that introduced me to Kentucky. After film school I went back to the region to make a documentary about mountaintop removal coal mining called Deep Down – and all along I wanted to make a film about the Appalachian stereotype in film and television, which I always viewed as hypocritical and incredibly damaging. When “Orange is the New Black” came out a couple of years ago featuring the character of “Pennsatucky,” who was completely two dimensional and stereotypical while the rest of the show was progressive, that was the straw that broke the camel’s back. I decided it was time to make this film.

Have you encountered the hillbilly stereotype? Please share an anecdote or two.

AY: My first memory of feeling like an outsider was when I went on a class trip with the speech and drama team to New York City when I was a sophomore in high school. I remember feeling like I should say as little as possible so that I wouldn’t be teased about my eastern Kentucky dialect. I must have learned that there was a stigma from the books I read and from the portrayals of mountain people in movies and on television – I don’t know where else that would have come from. That was my first memory of learning to keep my Kentucky accent secret. Fast forward a few years and I found myself in a similar situation although this time I was in Kentucky a couple hours west of where I grew up in Pike County. I often tell folks that the greatest culture shock of my life was moving to Lexington when I was 18 and being told bluntly that I needed to lose my accent if I wanted a successful career as a journalist. That was a transformative moment and when I realized that I was perceived as different – as an other – because I grew up in the mountains. I made a huge effort to divorce myself of my accent and it wasn’t until many years later when I moved to Los Angeles that I was able to embrace, accept, and not work so hard to hide it.

SR: In the media almost every day, most particularly with redneck reality tv, the latest smash hit that is blowing up the airwaves. But more personally, I always felt that my friends in New England were hypocritical and I never understood it. The very same people who would never say the “N” word, or other slangs aimed at disadvantaged groups, took pride in putting down poor, rural folks. Why? The double standard has always infuriated me.

Why is the stereotype misguided or inaccurate?

AY & SR: We have the great fortune of working alongside so many wonderful advisers on this project, including Silas House, an Appalachian author and Berea College professor; Tony Harkins, author of Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon; JW Williamson, author of Hillbillyland, What the Movies Did to the Mountains and What the Mountains Did to the Movies; Barbara Ellen Smith, a women’s and gender studies professor at Virginia Tech who has written about whiteness and the complexities of race in Appalachia; and Lora Smith, a community advocate from the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation and the Kentuckians for the Commonwealth.

Barbara Ellen Smith speaks powerfully about stereotypes and in her interview with us said that “Stereotypes are ugly. They do vicious cultural work and suggest that these people are not like us. We have nothing in common. And not only do we have nothing in common, but their behaviors and their traits are so deplorable that we don’t want to have anything in common with them. We need only make fun of them. We need only neglect them. We need only degrade them. That’s all they deserve. There’s a viciousness in that that is so inhumane and also justifies so much harm to the region and its people.”

We are grateful to these folks for sharing their work and inviting us to explore a vibrant discussion taking place in the fields of Appalachian, cultural, women’s, and gender studies. Their work helps us navigate this very complicated discussion about identity and identity politics; understand the social, cultural, and political nuances therein; and shine a light on the interconnectedness of race, class, gender, and sexuality.

We also had the great fortune of interviewing Bell Hooks, a native Kentuckian who has written extensively on feminism, popular culture, and media representations. We are greatly inspired by her discourse about mass media representations of poverty and the poor, which she writes about in her book, Belonging. “Mass media representations of poor folk in general convey to the public the notion that poor people are in dire straits because of the bad choices they have made. It pushes images that suggest that the poor suffer because of innate weaknesses of character. When mass media offers representations of poor mountain folk, all the negative assumptions are intensified and the projections exaggerated.”

Can you elaborate on the socio-economic impact(s) of the stereotype?

AY&SR: The main socio economic impact of the stereotype, we believe, is that people internalize what they see. Silas House, our Executive Producer, says “The thing that I have seen time and again from these media portrayals is that it produces shame and self-hatred in a lot of young people.” This shame has socio economic ramifications, and serves only to bring the region down.

How have the Appalachian people been represented in the media and why do you think that is?

AY&SR: There are many representations and interpretations to consider when we talk about media representations of Appalachian people that go back to the late 1800s and the work of John Fox, Jr. to the silent movie era to the television era of the 60s that saw great success with shows such as “The Beverly Hillbillies” to the movies of the 70s – Deliverance being the classic example – and now what we refer to as the redneck reality television genre.

AY&SR: There are many representations and interpretations to consider when we talk about media representations of Appalachian people that go back to the late 1800s and the work of John Fox, Jr. to the silent movie era to the television era of the 60s that saw great success with shows such as “The Beverly Hillbillies” to the movies of the 70s – Deliverance being the classic example – and now what we refer to as the redneck reality television genre.

AY: I’m going to speak from my own personal experience on this one because of the impact these media representations have had on my sense of self. I am 34 years old and was born in 1980. Growing up it was a common occurrence to see eastern Kentucky featured on the national news. I remember so clearly one program that aired when I was in third grade. I remember not wanting to watch it because I knew it wouldn’t feel good. At school the next day everybody was talking about the show and there was this shared sense of shame because of the way our eastern Kentucky community was portrayed. In a contemporary context, I have similar feelings about all of these reality shows that are being made in Kentucky and rural America. Perhaps the most complicated part of all is that those journalists and producers may not even understand that the work they are making is harmful.

It’s not all bad though! When I was an undergraduate student at the University of Kentucky I remember watching Barbara Kopple’s Academy-Award winning film Harlan County USA (1976) in a sociology class. That film moved me deeply. It tells the story of a coal miners’ strike in Southeast Kentucky and portrays its subjects with complexity, dignity, and grace. The film is as journalistic as it is cinematic. It’s personal, political, and emotional — a film that demonstrates social issue filmmaking at its finest. Seeing that film was an ‘aha’ moment because it was the first time I saw the people of east Kentucky be portrayed in a way that was nuanced and complex and it was unlike so many of the mass media portrayals of rural people I saw growing up, which were ultimately negative and hateful. This film, along with Anne Lewis’ Fast Food Women (1991) and Elizabeth Barret’s Coalmining Women (1982) show the power of documentary film to address significant social issues of our time. Their portrayals of Appalachian folks inspire us greatly.

What do you hope to achieve with your documentary?

AY&SR: Our intention in making this film is to create a diverse portrait of Appalachia, mountain, and rural people that inspires a new perception of Appalachia and its people into American public discourse. The film incorporate the points of view of Appalachian residents and scholars in an effort to portray Appalachian people as nuanced, multi-dimensional, and complex. The film also profiles a number of young media makers from Berea College and students from campuses all over the Appalachian region. Part of the goal of the film is to empower young people growing up in the mountains to make their own art and tell their own stories. We are building out the film over various social networks in an effort to engage and collaborate with rural communities all over the United States and eventually the world.

The film promotes tolerance and seeks to provide solutions for counteracting stereotypes on a broad level. We want to increase awareness and sensitivity around the use of two-dimensional language and humor that depicts the rural working poor negatively. We intend to expand viewers’ notions of the concept of “othering,” so that audiences think critically about societal behavior in separating, disconnecting, and ultimately critiquing other, less familiar social groups. The project takes on social goals that extend far beyond the re-conception of Appalachians, becoming an impetus for change on a broad and personal scale.

When does the artist (producer, director) cross the lines of observation/portrayal and into voyeurism?

AY&SR: Documentarians in all genres– the written word, the visual image– all walk the line of observation and voyeurism. It is an easy one to step over. This is no different in The Hollywood Hillbilly. Our effort as filmmakers is to capture our subjects and their central conflicts and to portray those with dignity and grace, all the while telling a compelling and cinematic story. Sometimes this is not so easy. One of our subjects articulates the challenge of a documentary storyteller this way: “Media of a place will inevitably be biased. How can the [documentarian] take apart archetypes, demystify stereotypes, represent culture, sum up experience, and interpret memory and history? We must not overburden [our work] with something it cannot do. Instead, we must acknowledge the maker’s hand, and our reactions.” We agree with this, and utilize this principle as a guide in our creation of The Hollywood Hillbilly.