by Paul Michael Brown

Today was suited for reflection. A dense, gray pallor hung low in the sky as I made my way by train from New York City to Union, NJ. I was headed to see ‘Las Desaparecidas de Juárez: Homage to the missing and murdered girls of Juarez’, an exhibition by Lexington-based artist Diane Kahlo, now showing at Kean University’s Human Rights Institute Gallery through January 15th.

The exhibit functions as a memorial to the women and girls, now in numbers estimated at more than 1000, who have disappeared from the city of Juarez in the last several decades.

Juarez is a Mexican town that sits on the border, a stone’s throw from El Paso, Texas. Maquiladoras, factories infamous for low wages and poor working conditions on which the U.S. relies for products reliant on cheap labor, dot the landscape and employ much of the town. The majority of the work force at these factories is made up of young women, who are favored because they are less likely to complain about long hours and tedious, repetitive work than men.

Juarez is also one of the major sites through which drugs are trafficked to the United States. Relatedly, extreme gang violence has led the city to be dubbed as one of the most dangerous in the world.

A particularly heinous grouping of murders dubbed as ‘femicide,’ or violence directed explicitly towards women with no discernible motive other than their gender, has come in two major waves, one peaking in the mid-late nineties, and the other more recently in 2012, but has never completely been completely stifled since it’s beginning.

The story of the murders and disappearances is difficult to pick apart, obscured by poor information, police corruption, and lack of adequate resources to properly assess and investigate the crimes.

Initially, the disappearances were thought to be the work of one or more serial killers, but as time progressed, numbers of those dead or missing climbed steadily, even after prime suspects were apprehended and tried.

Blame was placed on disparate groups by a public and a police force desperate to find someone to hold accountable. Suspects ranged from a group of bus drivers, violent husbands and fathers, to corrupt policemen, the international sex trade, and the gangs who have dominated the town for years.

Bodies of women and girls, some in their early teens or younger, are continuously found, often mangled beyond recognition, sometimes in mass graves, many bearing evidence of sexual assault. The local and federal authorities have been criticized for botching the investigations.

Bodies are not always recovered, leaving many families without necessary closure. A significant number of the cases remain open, with a bleak outlook for justice. This has pushed Kahlo, and other artists (most notably street artist Swoon with her memorial to the women realized in 2007) to create work celebrating the lives of these women and bringing awareness to their deaths, making sure that we do not forget the incredible loss to the community of Juarez and to the global community at large.

Kahlo’s memorial has been shown across the country even as the disappearances continue to occur, keeping the situation in Juarez on the minds of many. According to some sources, the homicide rate in Juarez has been on a steady decline since 2012, prompting those who were wealthy enough to flee temporarily to El Paso during the height of the killings to make their way back home and begin to resume business as usual. Abandoned storefronts are beginning to reopen, people are slowly becoming comfortable enough to walk along the ‘safe corridor’ of well lit bars and restaurants at night.

Heavily armed guards, however, still man the entrances to the freshly reopened, neon-illuminated night clubs.

The cause of this shift seems to be related in large part to the end of the power struggle between the two major gangs vying for power in the area, the Sinoloa and Juarez cartels. The war is believed to have been won by the Sinoloa cartel, but only by a narrow margin. Many of the leaders of both groups have been killed or jailed in recent years, significantly affecting the manpower needed to sustain a war of such violence.

Many residents are doubtful of the permanence of this peace, fearing a swift return to dangerous conditions if the Sinoloa cartel is challenged again. Additionally, because the perpetrators of the femicide seem to be not only linked to the drug war, quelling one potential source of the violence and ignoring others will not likely ease the minds of the people in Juarez.

Kahlo’s work allows us to begin to mourn those lost; to attach names to a number of missing and dead that is hard to comprehend.

On the right hand wall of the gallery hangs a grid of small painted portraits on a background of gold leaf, framed in deep purple, with the names of those depicted carved in shallow relief. The work is reminiscent of Christian icons, casting the women in a heavenly light, requiring us to get very close to the image to see it in detail, inspiring intimate, personal reflection. To have one’s entire field of vision occupied by hundreds of those who have had their lives cut short in such a way, to see the extreme youth of many of the victims, inspires a profound and guttural response.

One girl, Silvia Elena Rivera Morales, is depicted in her quincieñera (sweet sixteen) dress, smiling brightly. Images of small birds, sacred hearts, and butterflies stand in for victims whose photographs were not available.

References to both Christian and pre-Colombian spirituality tie conceptual and visual threads between the works, which show distinct mastery of several media by Kahlo.

Two grids of skulls decorated with intricate patterns of sequins face opposite the ‘Wall of Memories’ making reference to Dia de los Muertas, originally a celebration of indigenous peoples (likely Aztec) which has been co-opted by Christian tradition. The skulls serve as a symbol of death and rebirth surrounded by Mexican marigolds which are meant to attract the souls of the dead to the offering. Between the two grids is affixed a large embellished coffin decorated with the sacred heart, of Christian origin which implies both suffering and redemption, and a large sun reminiscent of the Aztec calendar, again calling into mind the cyclical nature of existence.

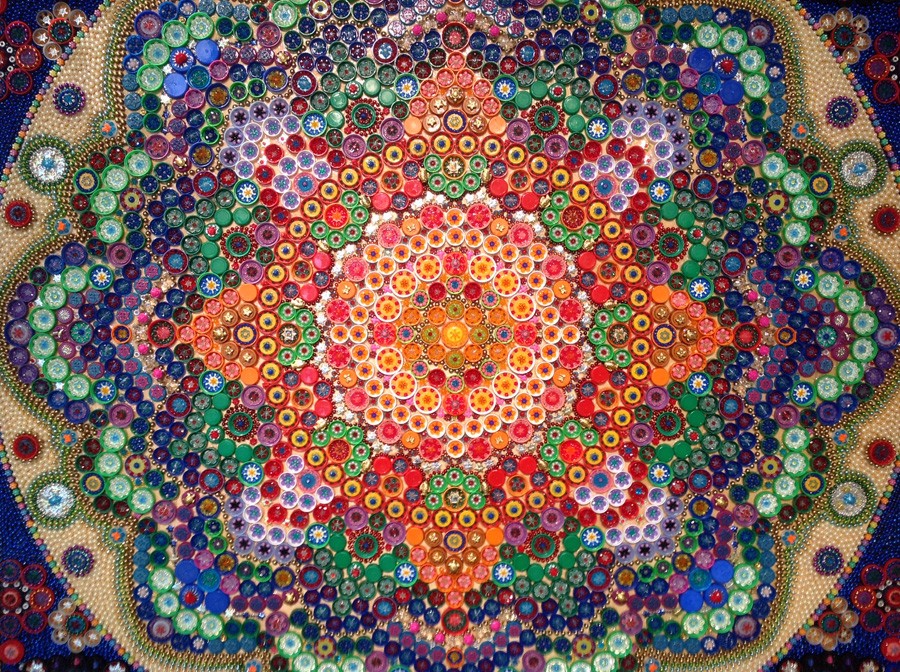

At the focal center of the exhibition is hung a large, densely colored Mandala (a form mirrored in both Aztec and Christian traditions, among many others) constructed from bottle caps, small trinkets, and junk jewelry Kahlo collected from flea markets, objects cast off or lost, assembled and organized to make a beautiful, shining whole. This is Kahlo’s most subtle, poetic, and effective work in the show. It brings together disparate visual references to the spiritual and material realities of the women affected by the situation in Juarez, and provides an intensely beautiful space for reflection and healing.

The memorial is successful in tying the specific struggle of these women to issues endemic to women worldwide. We are able to mourn the loss of these women and girls, and through them begin to understand the parallel struggles of our mothers and sisters, to gain insight into violence and inequity directed towards them.

Additionally, Kahlo has provided a vessel in which to put this awareness; to move from understanding to concrete action by the inclusion of a list of organizations dedicated to ending the violence and ways to help them in their efforts.

Previous to this exhibition, the show has travelled across the U.S. and has been utilized as a tool to both raise awareness and inspire action. Mexican activist group Yo Soy 132, in solidarity with the mothers of some of the disappeared women, used the exhibition to raise money to offset legal fees and living expenses of those left behind.

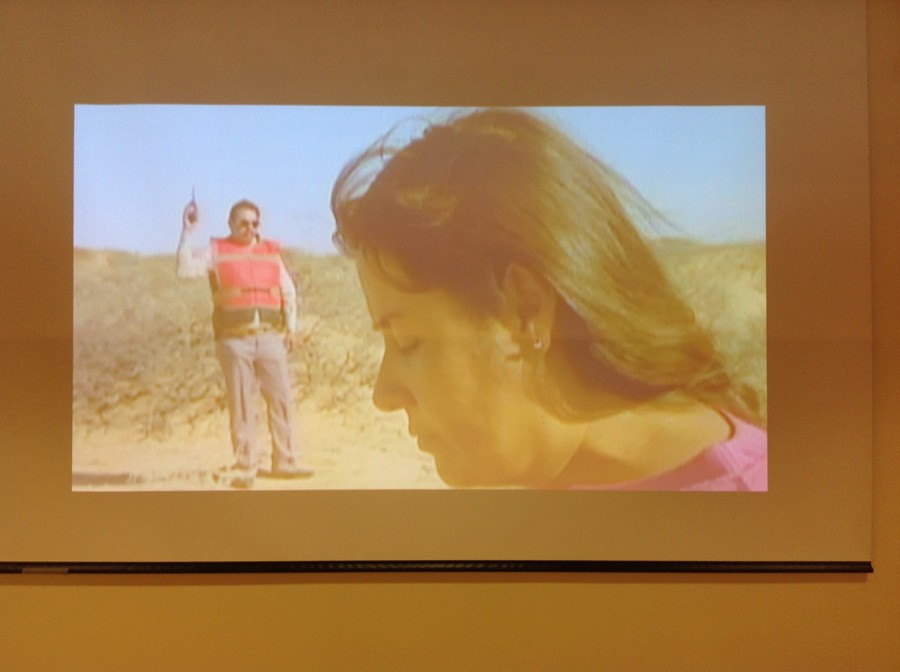

Kahlo has also partnered with documentary filmmaker Lourdes Portillo to create a short documentary outlining the situation in Juarez (also on view at the gallery) and calling for an immediate end to the violence.

We can make sure the names of these women are not unsung and celebrate the lives they lived, but such a memorial would be hollow without an opportunity to act. We should not only tell of the lives of the women affected, but are obligated to call out the individuals and larger social structures that allow this and other analogous offenses against women elsewhere to continue.

We should recognize that United States policy has shaped much of the economic and social reality of this place. We have taken part in an economy that depends on cheap, exploitative labor. We must see that these same economic structures often make drug trade an attractive option when faced with the realities of one’s own survival and the survival of one’s family; that when people feel disempowered socially and economically, they sometimes resort to violence against those who are more vulnerable than them to maintain some sense of power and agency.

These are of course not excuses for the actions committed against these women, but they are the structural underpinnings against which our anger and our action should be directed if we seek real and lasting change. Kahlo’s response to this situation provides an initial step in understanding and combatting this complex issue.