Illustrations by Ronald W. Davis

What a year Crystal Wilkinson is having! The Lexington writer’s 2016 novel The Birds of Opulence has been receiving renewed attention; its publisher, the University Press of Kentucky, recently released it as an audiobook. She won an O. Henry Award for a short story, “Endangered Species: Case 47401,” published in Story. She recently sold a culinary memoir with recipes, Praise Song for the Kitchen Ghosts, to Clarkson Potter/Penguin Random House, a major New York publisher. In April she was named the new Kentucky Poet Laureate, becoming the first black woman to hold the post. And just last week, the University Press published her first poetry collection, Perfect Black.

It’s no typical debut. Although Wilkinson, now in her late 50s, has focused on prose for most of her career, poetry has been a significant offshoot all along, dating back to her days as a co-founder of the Affrilachian Poets more than two decades ago. Perfect Black, a distillation of her best work in the genre during that considerable span (along with densely textured essays presented here as prose poems), reads like the collection of a seasoned writer who knows just what she wants to say and how she wants to say it, a rare quality in poets of any age.

Encompassing and bridging Wilkinson’s childhood, youth, and mature adulthood, these mostly straightforward, immediately accessible poems constitute a sort of autobiography-in-verse. It’s the story of a young black girl growing up in the loving hands of her hard-working grandparents, who raised tobacco, sorghum, hogs, and other things on their farm in the predominantly white community of Indian Creek in Casey County, Kentucky; of her young womanhood, which was marked by sexual and racist violence as well as growing self-awareness; and her increasingly sage later years. In this last period, she reckons both with personal sorrows, including her mother’s absences from her life due to mental illness, and the lingering legacy of slavery going back for many generations of her family, especially along matrilineal lines.

The book’s dramatic arc is the struggle against societal forces (including racism, misogyny, lookism, and the anti-rural bias she faced even from her own city cousins, who ridiculed her Kentucky twang as “country”) on a journey toward self-acceptance. In Perfect Black, Crystal Wilkinson doesn’t just overcome. As Nikky Finney suggests in an introductory essay, Wilkinson becomes, bruised but triumphantly intact, and proudly, perfectly herself.

In the process, she reclaims and consolidates parts of her identity that might otherwise have been lost forever. These include her culinary lineage – food and cooking loom large in this book as a kind of retrieval system, transporting her back to her grandmother’s kitchen and the landscape of her childhood – and her accent, which she consciously smothered for years before unfurling those expansive “country” vowels once more. In “Terrain,” the richly layered prose poem that opens this volume like a full-throated church anthem, Wilkinson charts her pattern of pulling away from her rural roots, then being pulled back by a force as implacable as hunger itself:

The map of me can’t be all hills & mountains even though i’ve been country all my life. The twang in my voice has moved downhill to the flatland a time or two. My taste buds have exiled themselves from fried green tomatoes & rhubarb for goat milk & pine nuts. Still i return to old ground time & again, a homing blackbird destined to return. I am plain brown bag, oak & twig, mud pies & gut-wrenching gospel in the throats of old tobacco brown men. When my spine crooks even further toward my mother, i will continue to crave the bulbous tang of wild shallots, the familiar game of oxtails & kraut boiling in a cast iron pot. I toe-dive in all the rivers seeking the whole of me, scout virtual african terrain sifting through ancestral memories, but still i’m called back home through hymns sung by stout black women in large hats & flowered dresses.

This central theme – the poet’s toggling between old and new, rural and urban, her original and constructed identities – boomerangs through the book in a cycle of self-estrangement and self-affirmation. In a different prose poem, “On Being Country,” she describes taking speech classes to erase the distinctive twang in her voice, “constantly trying to disprove that i was a black version of Elly Mae Clampett or Daisy Duke.” Years later, on extended visits to Indian Creek and at gatherings of the Affrilachian Poets, who met weekly “to embrace everything that made us who we were,” Crystal Wilkinson gets her groove back: “Country is as much part of me as my full lips, my wide hips, my dreadlocks, my high cheekbones. The way the words roll off my tongue is the voice of my people.”

But going home, in memory or otherwise, also means confronting and coming to terms with the trial by fire that was growing up black and female in the hills of rural south-central Kentucky in the ‘70s and ’80s. Those who tried to prey upon her included a distant relative, a deacon at her church: “The first time his hands brushed against my breasts, I thought it was an accident,” she writes in “Dig If You Will the Picture.” “He groped me the next time I rang the bell. After that, he looked for opportunities. I began hiding, but he always found me. And I kept the secret.” More often the aggressors were white boys at school who “extended their hands into the aisle when I boarded the bus in the mornings. One grabbed a right breast. Another grabbed a left buttock. Another grabbed my crotch. I tried to use my books as a shield but still the boys would get me, their hands taking what was not theirs.” She was consoled, in part, by the music of Prince, which she listened to in her room “under the glow of a cheap black lightbulb.” “My Prince. Beautiful. Black. A few years older than me. He told me that I was desirable – that when I was ready, my body was mine to give.” But when she turned 17 and went to college at Eastern Kentucky University, she was raped twice by the end of her first year. “Once by someone I knew and once by a stranger. I contemplated murder. I contemplated suicide.”

It’s Wilkinson, as a mature woman and successful writer, who gets the last word, in the form of this book. One poem in particular, “Dear Johnny P,” is a scalding bit of score-settling. Addressed to a white tormentor who “used to call me aunt jemima / grabbed at my breasts / asked me for some of that chocolate cow’s milk / hate in your face / disgust in your eyes / You called my friends nigga lovers,” the poem describes an encounter with the man many years later. He’s conciliatory, up to a point, but Wilkinson is in no mood for half-measures. “You said it was good to see me again / said you were proud of MY success / said my kids were a nice lookin bunch.” Then:

I saw you remember

saw the halfhearted/guilt-ridden apology

creeping from your eyes

saw some sorrow

But i wanted to hear it

from your white mouth

to my black ears

But you couldn’t

wouldn’t say it

But i know you remember, Johnny P / just like i do / i know you remember

(Note to Johnny P: If you feel that Wilkinson goes hard on you in this poem, consider the fact that she didn’t use your full name. All things considered, she let you off easy.)

It’s hard not to feel that the strongest work in Perfect Black comes in the prose pieces, where Wilkinson’s flow is unimpeded by line breaks and other formal trappings of poetry. Prose lets her build up heads of rhetorical steam; even better, it allows her to riff and ride the currents of language in a way that best captures that country voice she has rediscovered so painstakingly.

And speaking of impediments*: Careful readers of this review will have noted Wilkinson’s inconsistent spelling of the first person singular pronoun, sometimes as I, other times as i. (It’s usually i when not the first word of a sentence – with certain exceptions, such as in “Dig If You Will the Picture,” quoted above, in which it’s consistently I.) What to make of this? Is the lower-case i a sign of self-diminishment, even self-abnegation? Readers can be forgiven for making this semi-logical leap, but that interpretation makes no sense in a book about becoming, and asserting, oneself. It seems more likely to me that Wilkinson’s lower-case i – like her mostly consistent use of ampersands as substitutes for the word and – signifies her artistic kinship with other black and feminist writers. These include some of the Affrilachian Poets, their forebears in the Black Arts Movement and, perhaps most relevant, Ntozake Shange, author of the famed “choreopoem” for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf (1975), whose consistent use of the lower-case i was influential despite the fact that the piece was largely meant to be seen and heard on a stage, rather than consumed on a page. Whatever Wilkinson’s reason for using these shifting spellings of the word, I found them, as a reader, a bit of a distraction at first, a series of cognitive blips that kept getting in the way of my complete absorption in these otherwise exquisite lines. After a while, I became so engrossed in the book that these linguistic speed bumps became less and less jarring. I ended up feeling that they’re simply part of the hilly terrain of the book and, certainly, no hill to die on.

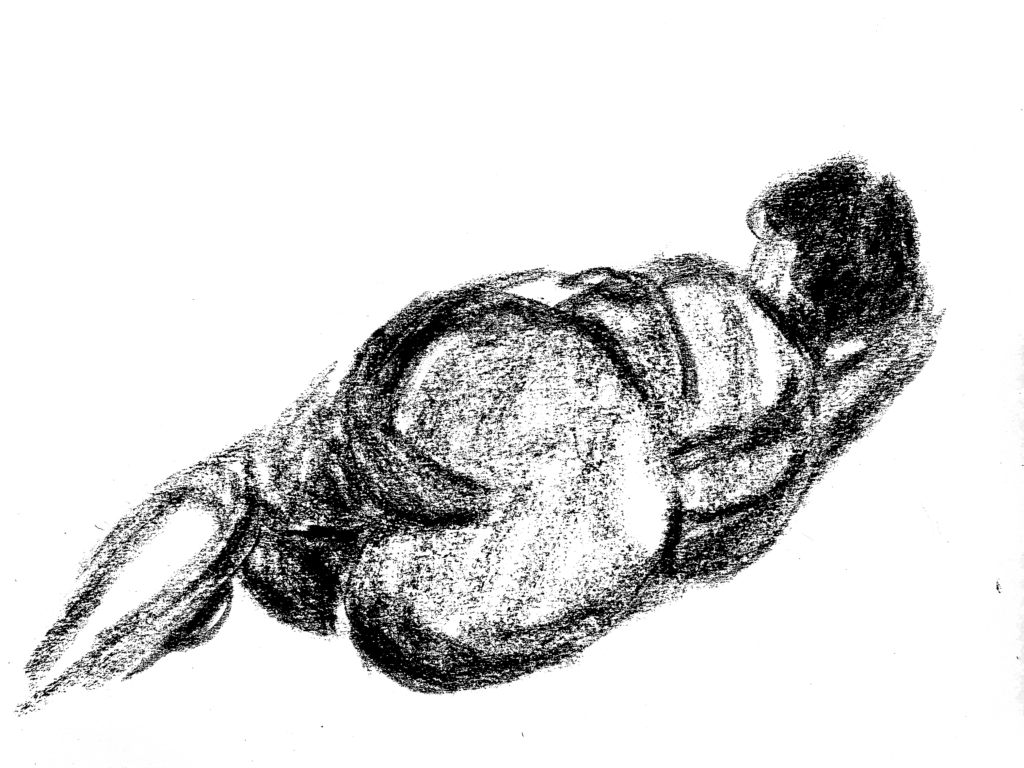

Let me end here with an appreciation of Ronald W. Davis, an artist and Wilkinson’s longtime partner, whose illustrations interpret, adorn, and punctuate Perfect Black in the most felicitous and sensitive way imaginable. I especially love the cover image, which conceives a black woman of piercing eye and sensuous mouth who is also indivisible from the natural world of her memories; and the illustrations for “Terrain,” in which the poet is imagined as mystic dreamer, and “Black Body,” in which she appears as a regal figure with her head in a turban, her hands on her hips. Davis also surfaces as a romantic hero in two of the book’s most meltingly beautiful poems, “Witness” and “Black & Fat & Perfect,” which concludes with a domestic scene blissful enough to redeem almost all of the pain that preceded it in this powerful collection:

Light dances in the window

& the work of morning begins.

He brews the coffee. She turns the sausage.

He scoops her waist from behind,

cups the girth of her belly & she is black & fat

& perfect in his capable, warm hands.

*During an interview for Eastern Standard, Tom Eblen asked Crystal Wilkinson about her use of upper and lower case for the pronoun “I”.