Art, poetry, and music are basically cut from the same cloth—a fabric of the imagination inspired by the “real,” a concept as impalpable as any of the artistic processes that strive to represent it (reality). Goethe wrote that “Music is liquid architecture; Architecture is frozen music.” While this expression may make our wheels of cognition wobble a little, it is comprehensible, it is imaginable, and it is poetic. If you listen to Debussy’s The Sunken Cathedral, or if you look at any of Monet’s several paintings of Rouen Cathedral, the beauty, the emotion, and the lyricism that Goethe’s words and these great works of art share become magically palpable. So the formidable and rewarding task of any successful artist, regardless of the discipline, is to internalize his or her perception of the world and deliver it to us in a way that helps deepen our own experience and understanding of our place in it, of what it means to be human.

Lexington artist Patrick Adams has stood on the cliffs of his imagination and stepped up to this easel many times. He lives and breathes his art as he continuously endeavors to explore the parameters of possibility and to realize the full extent of his creative potential.

Adams grew up in the rural farming community of Worthington, Minnesota, a landscape that ignited his spirit and became the dominate subject matter of his work with its “tall-grass prairies, vast horizons, dramatic light and thousands of natural lakes.” Since moving to Lexington over two decades ago to obtain his MFA at the University of Kentucky, he has come to recognize and acknowledge an equal love for the Kentucky landscape as well.

In a recent article published in The American Scholar (March 20, 2017), Adams says of his work and process that, “When people ask me, ‘Are these real places?’ I say, well, yes and no. They begin there, but where they end is somewhere else . . . The memory is part of my process. I like what the memory does to the image. I want the details to slip away . . . I like how the memory distills or exaggerates things, or remembers in the landscape something really essential, just the dominant essence of the scene.”

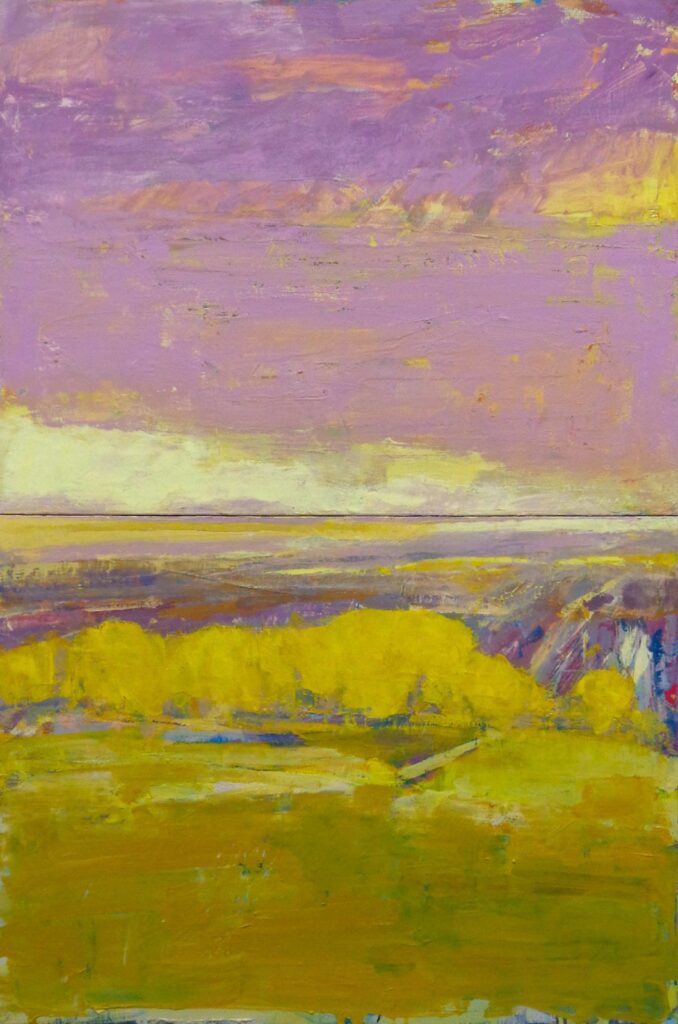

Hilltop and Lavender Sky is an awe-inspiring example of what Adams is aiming for. And it hits the mark. Everything about this composition epitomizes the “essence of the scene” from the soft shapes and ethereal hues of lavender, yellow, and green to the sparse, deeper terrestrial tinges of white, red, and blue. Its subtle power and strong spirit make it an extremely important work of art because each time we look at it, it speaks to us in a different way, deepening our appreciation of it and strengthening our connection to it. It speaks of something beyond the physical world, of something eternal within nature and hence within ourselves. It enables the soul to take flight. For me, it brings to mind the countless times I climbed the hilltops near my childhood home looking at the layers of mountain ranges stretched out before me and standing in awe of the infinite space above me thinking this is probably as close to heaven as I will ever get.

This piece was a part of Adams’ diptych series, In Two Worlds, exhibited at the Ann Tower Gallery, January – March (2016), a body of work that probably best represents his poetic and abstract concept of art as metaphor. Each diptych incorporates two canvases of equal size placed flush one above the other, doubling the surface space of the painting. But Adams explained in his artist statement for this show that the idea behind the diptychs goes far beyond the materiality of the canvases: “I have divided the landscape image along the horizon into two physically separate paintings: the lower half (earth), representing the physical realm, and the upper half (sky, the ‘heavens’) representing the metaphysical, or spiritual realm. These two parts, seen separately, appear flat and incomprehensible, but once brought together, they form an image that acquires an unexpected unity of light, depth and meaning . . . the physical and spiritual worlds are brought together as one, each illuminating and clarifying the other.”

Meadow Stream succinctly illustrates this point. The individual sections are completely abstract but as with all the paintings in this series, when combined, they are like the yin and yang of art—complementary elements coming together to create a harmonious whole.

My first encounter with Adams’ artwork was at an earlier exhibit, Real Presence, at the Ann Tower Gallery in 2004. From that point on, I was sold although I couldn’t really afford to buy. A couple of years later, though, I lucked out and was able to purchase a small matted and framed oil on paper, Prelude 23, at a silent auction for the annual Art in Bloom event at the University of Kentucky Art Museum. Then, as either serendipity or synchronicity would have it, about a month ago I managed to meet with him in his studio for an interview and to learn more about what lies behind his prolific and successful career as an artist and the philosophy and influences that govern his approach and style, a little of which we have already touched on.

Adams went to school at the height of post-modernism, but said it did not have a big impact on his painting because he felt it would not sustain him for very long. It appears he took the high road—and the open road—by absorbing specific concepts, subject matter, and technical nuances of some of the greats: “The kind of artists I’ve been responding to over the last 20 years have been somewhere between late romanticism and impressionism all the way up to contemporary artists. Corot (French) and Kensett (American) paid a lot of attention to light and atmosphere and even though they were romantics (mid-19th century), that’s where the seeds of impressionism and expressionism were sewn.” While both these artists still have a strong influence, Adams says, “Abstract expressionism (abex) pretty much describes my work. If you put those two ideas together, that’s really what my work is. If you took these two words [abstract and expressionism] and put them in a bag and shook it, my work would come out.” He admits a partiality to Van Gogh because his own markings, which he characterizes as jittery or fragmented surfaces are sometimes quite similar. This can easily be seen in his diptych, Pleasant Hill. Yet it is distinctly his own.

Here Adams draws on the tremendous energy generated from the good earth and the big sky. The scene vibrates with motion and color and the elements are bold, and the gestures grand and striking. The luminosity and atmosphere that emanate from this painting can only be revealed by natural light, or the memory of it, regardless of where it was painted—in the studio or outdoors (plein air). The reality of this landscape has been deeply internalized, merged with the artist’s inner self, and he has allowed this integration to charge his imagination and guide his brush and his palette knife over the canvas time and again, layering the scene into existence. It is abstract expressionism simultaneously contained and gone wild. It is a landscape that refuses to stand still.

Besides giving a lot of credit to his former professors for helping him see and be, Adams did not ignore the influence of Monet’s later, more abstract and heavily textured works with which few of us are familiar, the ones we don’t see in art history books. He also paid homage to the late modernist Richard Diebenkorn (American colorist and structuralist) as well as the images of the contemporary Danish geologist, artist, poet and filmmaker, Per Kirkeby. One of Adams’ most abstract and most recent small pieces, Break, speaks volumes as an amalgamation of these influences and his own experience—a synthesis where the conscious and subconscious work in tandem to create a presence that is one thing when seen up close, but quite another when viewed from a distance. A genuine mark of artistic vitality.

Adams explains, “I use a ton of paint and paint over a lot of other good paintings that I’m not satisfied with to create this effect. I lose a lot of good paintings to get to the one I eventually keep but I think this approach is pretty indigenous to the abex genre.” And he remarks that regardless of the canvas size, “the landscape for me is an arena to address other things such as light, space, movement, color, and even smells and feelings.”

The sentiment he expresses in his artist statement is congruent in all his work and he challenges anyone who looks at his paintings to see the poetry too: “I want people to see the natural world not as a backdrop to their lives, but as the very heart of their lives. The beauty of these forms is not just to delight us (though it does), but also to give us life. Beauty is not simply an ornament, a surface phenomenon, but the essence and power of being. And, if beauty is accompanied at all times, as many great thinkers both ancient and modern have asserted, by goodness and truth, then we ignore it to our peril.” Then let us not ignore the beauty, goodness, and truth of Ascent of Light.

Light is a crucial element in all of Adams’ work, as many of his other titles suggest: Light Under Pressure, Light and Fog, Shaker Light, Veil of Light, Where Light Dwells, First Light, Uplight, and most important—Goethe’s Light. His philosophy that inquisitiveness is vital to being a creative person led him to the German poet and artist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s treatise on Theory of Color published in 1810, in which he (Goethe) hypothesizes on color as an interaction between light and darkness, why we see color, how we experience it, and how it affects us psychologically and emotionally.

Maria Popova in Goethe on the Psychology of Color and Emotion, observes that “One of Goethe’s most radical points was a refutation of Newton’s ideas about the color spectrum, suggesting instead that darkness is an active ingredient rather than the mere passive absence of light.”

“Light and darkness, brightness and obscurity, or if a more general expression is preferred, light and its absence, are necessary to the production of color,” noted Goethe. “Color itself is a degree of darkness.” Goethe’s Light may not contain the stirring brilliance you see in Ascent of Light, but it faithfully renders the more obscure “active ingredient” of color not uncommon in abex art.

When he was working on Goethe’s Light, Adams said he saw a different kind of light, a luminescence emerging from darkness:

For Adams, these forces also include music – he plays a number of instruments and composes as well. While Pythagoras’ theory on harmonics is more exact than Goethe’s on light and color, the effect that music has on us is just as powerful. So I asked Adams to elaborate a bit on the connection between his art and music, and he jumped right in.

He has been painting (and selling them) since he was ten years old, and his interest in music at this young age was also well beyond that of a neophyte. He was awarded both an art and music scholarship (trumpet performance) his first year in college at Winona State University in Winona, Minnesota. But because of an injury he received while playing in college marching band, he had to quit playing for a while. He says that hiatus was actually fortuitous because it he made him focus more on his art, eventually allowing him to pursue a Masters of Fine Arts degree at the University of Kentucky where he was awarded a full scholarship and a teaching assistantship. And he hasn’t looked back.

In considering his love for making music and its connection to his art and creative process, it’s easy to see how one inherently feeds the other, even though he has chosen painting and teaching as a profession. He emphatically states, “If I had another career, I would like to write film scores because there’s a direct link between the music and the image.” As for his painting, he muses, “The ideal show for me would be where I would write a soundtrack for it that would be atmospheric and simple and spacious, similar to a landscape where you are the thing in the space.” I say go for it! It may not be a new concept, but it is most definitely a rare experience for gallery goers to be engulfed visually and aurally by the work of a single artist.

As we listened to some of his compositions in his studio, Adams pointed out that both his paintings and his music “are the result of a very intuitive and improvisational process where an idea begins to assert itself and is then embellished and refined, yet neither is without structure. Just as paintings derive from the landscape, the songs are structured in a traditional jazz format . . . The intended result is simplicity.” Because he plays each of the instruments himself, he records his music in layers (or tracks) similar to the way he constructs a painting: “Same process. I am building different layers and colors and textures, and the way they interact lets you ultimately see a single image or hear a single piece of music.” Take a listen to the title cut from his album, Solipsis, while viewing his Etudes (201 – 206) and experience it for yourself. Before you start, though, keep in mind that the titles have a bearing on the processes involved as the work was created.

Solipsis relates to the inner mind, thought, voice, feeling, and wanderings, in this case, as expressed through Adams’ individual and yet integrated performance on the electric piano, organ, drums, acoustic bass, and trumpet. Etude, a term mostly applied to a short musical composition that helps a player become more proficient on a given instrument, also refers to small studies that artists create as they formulate ideas for a larger work. Adams, again, hits the mark on all counts and here is a rare opportunity for you to get inside his head and bask in the reverie.

[SlideDeck2 id=10393 ress=1]

View Patrick’s work and listen to his composition, “Solipsis.”

From having worked on this piece for the last several weeks, the association of music with Adams’s painting has become fully ingrained in my psyche. With Harbor, for instance, I can see the interconnected layering and I can hear the music—music that I am creating in my own head as I stare at the essence of what a harbor looks like under particular circumstances or with its reality broken down into its basic components that become abstract, unrecognizable to my cranial dictates in relation to what I think a harbor should be or how I think a piece of music should sound simply based on its title. This is the beauty of the challenge in all of Adams’ work. It requires that you be with it, allowing it to permeate your senses.

In his words:

Despite his musical accomplishments, painting comes to the fore as Adams’ first love and he is very forthright with what sustains his creative spirit: “I love to paint. I like the physicality of it combined with the images I create. I’ll never get it perfect and that’s what keeps me going. There’s also something about the struggle and not knowing where you are headed. When I start painting [or composing], it’s like bumbling around in the dark and the more I can stay in the dark and stay lost, the more I like it in the painting [and the music]. Within certain boundaries, it’s exciting and to be lost in a work is good. The poetry of the creative act is in the struggle. The struggle makes art and art redeems the struggle.” Sounds a little like life, doesn’t it?

And then, there is the matter of the medium:

Through the on-going cycles of redemptive struggle necessary to the creative process, Adams has built up an impressive CV and portfolio. He has been a professional artist for over 25 years and is currently an Adjunct Professor of Art at the University of Kentucky, Asbury University, and Eastern Kentucky University teaching courses in drawing, painting, art appreciation, art theory and criticism, and others as his schedule permits. He is a two-time recipient of the prestigious Al Smith Fellowship in the Visual Arts awarded by the Kentucky Arts Council, and his past is awash with major exhibits (solo, two-person, and group), all over the country dating as far back as 1999. You can check out the details and his spectacular portfolios on his website, patrickadamsart.com.

His most recent exhibit of New Work was at Aberson Exhibits in Tulsa, OK last month, and he is participating in an upcoming group show (May 4-19), Dirty Pictures, at the Atrium Gallery – Studios on the Park in Paso Robles, CA. I bet that got your attention, didn’t it? Chill. It’s all about landscapes—the good earth! We wouldn’t expect anything less from Patrick Adams since many of his paintings can be found in a number of private and corporate collections, such as the James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute (Columbus, OH), Mayo Clinic (Jacksonville, FL), Hilliard Lyons (Louisville, KY), and Gaylord International Convention Center (Washington, DC).

I don’t think we have to worry that these successes will prompt Adams to stop painting and composing. He couldn’t if he wanted to because he seems to subscribe wholeheartedly to the idea in T. S. Eliot’s The Hollow Men that “Between the conception / And the creation / Between the emotion / And the response / Falls the shadow.” Without both darkness and light, between which that shadow lies, there can be no color, no landscapes. Adams’ knowledge of this means he can look forward to a great future—struggle and all! He himself declares, “My plan is to keep throwing paint at my canvases until something sticks that I can call good. I will likely die trying.”

(All images and music courtesy of the artist)

Related in UnderMain: Other Lexington artists who mix mediums

Ron Isaacs: Shelf Life (Painting, sculpture)

Patrick McNeese (Painting, music)