At first blush, it looks like a regular house, albeit a large and imposing one, but nothing externally gives the casual observer any indication of what takes place inside. The cinder blocks under the porch bear the dark stains of benign neglect. A small parking area might as well be a standard driveway for multiple occupants. There is no sign to denote the home of Shangri-La Productions, the local recording studio where a man by the name of Duane Lundy plies his trade.

This is probably for the better. Lundy is not the sort of man to call attention to himself, despite a career that has seen an extraordinary ascending trajectory from home recording hobbyist to respected producer and collaborator, locally, regionally, nationally and even internationally. That career may reach a new milestone on September 15th, when a new album by former Beatle Ringo Starr will hit the shelves (both digitally and analog…ly). On that album are two collaborations between Starr and local/national act Vandaveer, with Duane Lundy credited as the producer for both. Is this his moment?

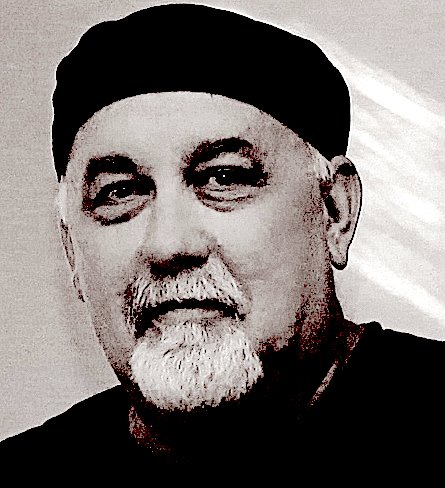

Sitting half off a small set of steps behind the house on a sunny July day, Lundy is attired in black Converse All-Stars, black jeans, a black shirt with round Lennon sunglasses folded into the collar, and his trademark black fedora, a portrait of unflappable cool in the unyielding heat. The sense one gets is not that he’s trying to stand out so much as that he’s just outside his natural habitat. Once he retreats into the sparsely lit confines of his home cum studio, his uniform makes more sense against the backdrop of a space designed to summon creative energies.

Shangri-La Productions is not your average studio. The studio itself is a creative reimaging of the first floor of a large Victorian house. Where bespoke studios have a master control room and carefully divided spaces for enhanced sound isolation, Shangri-La favors a connected set of open rooms for collaboration, with all controls as the focus of what might have once been a magnificent sitting room with a fire place. The only “studio†decoration staples are the large oriental rugs adorning the hardwood floors, but everywhere hang bolts of various patterns of shimmering cloth and strings of white lights, giving an aura of comfort, and at times resembling a carnival. Vintage keyboards, amps, drums and guitars line the walls and halls. The atmosphere is immensely inviting to musicians, and that is by design.

“The pieces of work that I grew up on and studied a lot on were Zeppelin albums and U2 albums and Bob Dylan albums,†Lundy says. “Most of those albums were done in alternative spaces, you know, like [The] Joshua Tree, or Zeppelin albums in particular, Exile on Main Street… so I really found a lot of romanticism with the idea of being able to create a unique space that people felt comfortable in that was lived in, and also that it was a little bit sort of out of the template.â€

If his studio aesthetic took cues from his favorite albums, his work process gained inspiration closer to home: Lundy’s former life as a tennis coach. That’s where he met Emily Hagihara, currently of Lexington staple Ancient Warfare, and formerly of Chico Fellini, a standout of the Lexington scene in which Lundy played guitar. At the time, however, she was a high school student taking tennis lessons where Lundy worked, and she believes that his experiences as a coach informs the way he approaches recording.

“He’s very much a coach, in a way,†Hagihara says. “He makes you feel welcome, and he encourages you to explore, but also makes you focus.â€

“I know that I’ve gone into the studio several times and second-guessed a thing, and he just sort of makes you concentrate on doing that thing until it either works or it doesn’t. He’s just very pragmatic.â€

Hagihara is part of Lundy’s increasing repertoire of consistent collaborators for mutual benefit. Her long musical history with Lundy has led to a harmonious working relationship over the past ten years or so.

“He likes, as well as I do, things that are a little rough around the edges, but I think we also like the juxtaposition or the marriage of those things that are rough but also beautiful, and figuring out how to make those two things work together,†Hagihara says.

The Lexington artist and songwriter Patrick McNeese, whose band has recorded several projects at Shangri La and is now in the process of another, credits Lundy for influencing the direction of the music scene in Lexington. “Writing a song, in many ways, is simply an invitation for other artists to contribute to the creation of a fully developed and engaging work of art. Duane is foremost another artist, one who understands this intricate and highly personal process and he has been able to develop the skills and temperament to achieve a consistently good outcomes in his studio. This is his unparalleled contribution to Lexington’s music and recording landscape.”

Lundy’s journey to his current role as Lexington’s music shaman took a circuitous route, with him getting a much later start than most music lifers.

“I was twenty-two and had never played an instrument before, and had always loved music,†Lundy says. “So, in starting late, I was pretty certain that being in a band or playing with other musicians that were my age was not going to be a possibility. So at the same time I got my first guitar, I also got a four-track [recorder].â€Â

Learning to play music alongside absorbing the fundamentals of recording allowed Lundy to gain an understanding of music from the perspective of writing and production, rather than just as a musician.

“I ended up learning really quick, which I think had a lot to do with just sort of my obsession with music,†Lundy says, “So I ended up being in bands within the first, I’d say, six months that I was starting to play.â€Â

For Lundy, learning to be a musician was great…

“But I really loved recording,†Lundy says.

Later, after a business venture with his ex-wife ended, Lundy was at a crossroads, a not uncommon place for musicians to find themselves (see Johnson, Robert, or Clapton, Eric). It was then that his burgeoning hobby began to take shape as a career.

“A really good friend of mine who had actually taught me how to play guitar had moved from Lexington to Miami to become a music supervisor at an ad agency. So he would send me work, and that really was a pretty big crossfade* moment in my development from being sort of a local or regional recordist to doing stuff that was going to reach a more critical ear,†Lundy says.

From there, Lundy’s career as a recording engineer, mixer and producer took off, handling commercial work for various media platforms, work that saw him travel to studios nationally and internationally, honing his skills.

“There were moments where I contemplated moving to an industry market – be it Nashville, or Los Angeles…New York. Wherever…the work is a bit more plentiful.â€Â

In the end, Lexington remained home, largely due to family considerations: his son, 17, and his daughter, 15, who both reside in the area.

Here’s the part where it would be easy to now try to paint Lundy as a martyr, an outsized talent duty-bound to lead a life less fitting than his skills deserve, but it’s all but impossible to nail him to that particular cross. He doesn’t disseminate an air of self-pity or remorse for the path that he could have taken if only he could shake these little town blues; he can state matter-of-factly that Lexington is not entirely ideal as an industry town, but there’s never a sense of bitterness or confinement.

“I love Lexington,†Lundy says, and there’s not a single note of hesitation. “It has certainly created a set of challenges for me geographically, because, you know, there’s really no infrastructure of industry – music industry – here.â€Â

He could be a fixture in an industry-driven town, but Lundy credits the disconnect from the larger industry as a motivation for his success; he is less susceptible to trends and stagnation than if he were tapped directly in to the industry undercurrent.

“Not being in an industry town, being in a place like this, I really don’t know what the latest way that guys in Nashville are miking their drum kits,†Lundy says. â€But I like it. I think naivety is immensely important in keeping your creative flow interesting and productive.â€

Lexington, however, is slowly accumulating industry credibility, if not music infrastructure, and it’s due in large part to Lundy and Shangri-La, as J. Tom Hnatow, a recording engineer, producer and musician at Shangri-La and member of Vandaveer, points out.

“It’s put Lexington on the map,†Hnatow says. “There’s been a level of recognition nationally and internationally. This city has been able to punch above its weight.â€

Hnatow speaks from experience on that point, having been lured from more urban centers to Lexington by Lundy with the promise of work at Shangri La.

“As a professional musician, I would have not seen myself moving to Lexington if not for Duane.â€Â

As proof of Lundy’s expanding influence, Hnatow points to figures such as Justin Craig, who came up as a session player with Lundy and has since worked on Broadway as Music Director for “Hedwig and the Angry Itch,†among other high-profile projects.

“In Lexington, the number of people here working as a session musician is unusual for a city this size.â€

The list of Lexington figures now achieving some sort of recognition on a national stage and beyond who have worked with Lundy is growing daily: Cheyenne Mize, Ben Sollee, Jim James of Louisville heroes My Morning Jacket and even newly-minted Grammy Award winner Sturgill Simpson, whose former band Sunday Valley recorded an album with Lundy before Simpson went solo.

After watching others ascend to new heights with a little help from his guidance, the spotlight may soon be focused more brightly on Lundy himself. Production credit for two cuts on a Ringo Starr album surely should bring attention to Lundy and his work, yet he downplays the suggestion that this a watershed moment for him, noting that he’s worked with legacy artists** such as Cheap Trick and others in the past. When pressed, he’ll admit to a degree of validation in the work, but he isn’t looking for the trappings of musical fame. Instead, Lundy frames his circumspect take on musical stardom with characteristic pragmatism.

“I love music to a degree that I wanted to continue to do it professionally, and I saw this as a means to continue to do it,†Lundy says. “And it just so happened I fell in love with doing it.â€

“I really like what I do, and I like to think that I’ll spend the rest of my life doing it. And that people will enjoy the time that we’ve had to work together and the people who get to listen to it, whoever that is, will enjoy what we did. No more, no less.â€

‘If I reach a point to where it’s not fun anymore, then I won’t do it. Because there’s other things that you can do and make less sacrifice for.â€Â

Duane Lundy doesn’t need to be a rock star. He’s not jealous of the ascendency of those with whom he has collaborated. He’s content as the black-clad figure at the controls in his own personal Shangri-La, radiating calm in the center of Lexington’s growing musical storm.

*For those unaccustomed to the recording lexicon, a crossfade is a transition between sound clips, where one clip fades out as another fades in.

**A professional way of saying “rock star.â€