There are plenty of ways to sing that sound interesting. There are, while admittedly fewer, still many ways of singing that sound pretty, or powerful, or pure. There is no way of singing yet invented that can match a fully developed bel canto voice.

Bel Canto, a vocal technique developed in Italy from the sixteenth century onward, is the open and clear sound, usually sung with a quaver in the voice called vibrato, and that’s stereotypical of the opera, and of classical music in general. It takes years for a singer to develop a proper bel canto voice, and singing with it, drawing breath from the diaphragm and propelling to the back of an often massive concert hall, is not just technically demanding but physically exhausting. It’s a way of singing that makes you sweat.

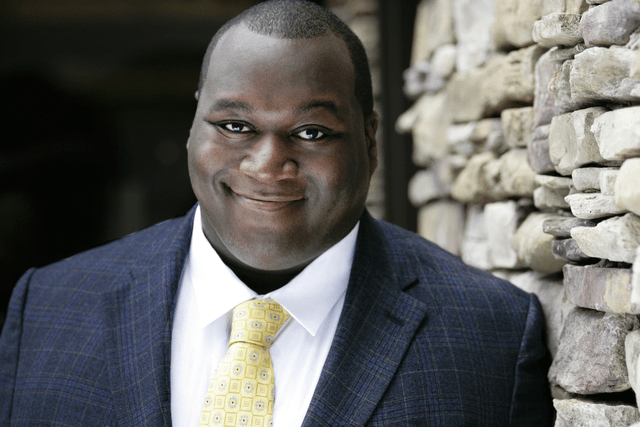

When the young bass-baritone Reginald Smith, Jr. dabbed at his forehead with a handkerchief, midway through the first act of the oratorio that he sang on Friday night, that exhaustion was beginning to show. He didn’t let it phase him in the slightest. The oratorio—a kind of long vocal work that incorporates orchestra, chorus, and solo voices—was Felix Mendelssohn’s Elijah, one of the most famous, and famously demanding, examples of the genre.

The Lexington Singers had invited Smith, along with several other soloists and the UK Chorale, another choral group, to join them in a performance of Mendelssohn’s Elijah. Performing in UK’s Singletary Center for the Arts (like many classical groups in Lexington), the Singers set themselves the challenge of filling up a concert hall that could swallow most bars or clubs without losing half of the seats.

When the Lexington Singer’s Chamber Orchestra joined the vocalists on the stage, the entire scale of the enterprise became hard to ignore—there were over one hundred singers, and nearly fifty instrumentalists, assembled for the sole purpose of creating over two hours worth of almost continuous music. The piece they were set to perform would require nothing less.

Felix Mendelssohn composed Elijah for an 1846 premiere; he died less than a year afterward, at only thirty-eight years of age. The oratorio, therefore, is the closest thing to a mature work that the young composer and former child prodigy left to the world.

Stylistically, Mendelssohn always made a habit of looking back to the delicate and precise music of the Bach and Haydn, as opposed to the radical innovations of contemporaries like Liszt or Wagner. While the early Romantic period that he lived through was in many ways defined by composers challenging the harmonic and structural components of the classical tradition, Mendelssohn would never push the boundaries of what harmony and traditional musical forms could convey—his chords are always clean, and they always lead exactly where you expect them to.

Nevertheless, Elijah strikes a balance between the old and the new of Mendelssohn’s time: while the overture has a formally complicated fugue motion that’s reminiscent of Bach, the thick orchestral textures and propulsive rhythmic intensity of the music point to an unmistakable Beethoven influence on Mendelssohn’s style. Creating those complex forms and textures requires not only a choir that can sing up to eight voice parts at once but a full orchestra to back them up.

Coordinating such a large number of people for a performance is a task that’s almost entirely reserved to the world of classical music (imagine a rock band with more than six or seven members at the most, and you understand why), and classical groups have a unique figure devoted solely to the task of keeping everyone on the same page of the score: the conductor.

Dr. Jefferson Johnson has served as the conductor for the Lexington Singers for many seasons now, and his ability to direct the choir, while formidable, clearly cannot compare to his ability to choose a soloist perfectly suited to the Singers’ performance.

Smith sang the title role, with a style that can only be described, appropriately enough, as biblical. With a throbbing, richly textured tone that conveyed every ounce of emotion that played across his expressive face, Smith leapt from a roaring castigation of the wayward Israelite King Ahab to a soft, subtle lamentation of the fate of his people, and in a searching, haunting aria, he found his way back to a joyful, soaring vision of a flaming chariot come to take him up to Heaven.

Smith has a voice that is too flexible, too widely developed and able to convey a breadth of emotions to offer easy categorization or comparison. Suffice it to say that he is a singer in impeccable command of an extraordinary talent.

Shockingly, Smith is still considered a rising star in the classical world, not yet fully arrived as a star in his own right. However, if his performance in Elijah is anything to judge by, Smith will be drawing comparisons to premier bass-baritones like Eric Owens before long—and some of those comparisons will be favorable to Smith.

The Singers, as a choir, also acquitted themselves well. The piece is noted for its rousing and overpowering choral movements. As the music built to climax after climax, the Singers’ voices bubbled, swelled, and rose like a tsunami to crash over the orchestra, the audience, and the building itself in an exactly controlled roll of passion into passion.

The orchestra itself played with a frenetic energy that clearly fed itself off of the remarkable vocal performances. In particular, first cellist Benjamin Karp managed to play with such a fury that he frayed his bow; he then went on to play a tender accompaniment to one of Smith’s second-half arias.

The other soloists also demonstrated the kind of vocal skill that it takes to perform a piece like Elijah. Contralto Shauntina Phillips enveloped the hall in a low, warm sound, even as the orchestra roiled and churned at full intensity behind her.

Soprano Amanda Balltrip pierced through the air with a light but wonderfully intense lilt as she sang, unexpectedly, from the back of the hall. Likewise, soprano Katherine Olson set her voice to fly above the assembled choral and orchestral forces and distinguished herself even among the talent around her. Tenor Taylor Comstock snaked his high, silvery voice through the audience and left the impression of a particularly delicate but beautiful flower.

That’s not to say there weren’t a few flies buzzing about the hall. Mendelssohn prepared the text of the oratorio in both German and English, but since its premiere in 1846, the English version of the text has predominated (to understand why you only have to listen to a few minutes of singing in German). The Singers chose to maintain the English text. Unfortunately, the chorus had a sometimes hazy diction that made it difficult to determine exactly what was being sung. There was also a consistent difficulty with the ‘sss’ sound—there were moments when it sounded as though the choir was beating back an infestation of snakes. Despite some minor setbacks, however, the evening was a remarkable success.

The story of Elijah is the story of a prophet reprimanding his people for wandering from the path of righteousness. If they wandered into this performance, even the taciturn man of God would be hard-pressed to find a reason to condemn them.