Like any great magician, Ben Monder saves his wildest trick as a parting shot.

The setting is the New York guitarist’s current album, “Day After Day,†a double-disc offering that shakes up the well-utilized concept of the standards record. The first disc is just Monder on his own offering a set of generations-old gems by Henry Mancini, Johnny Mandel and Burt Bacharach that might suggest – on paper, at least – that Monder is an immovable traditionalist. One listen to his distinctive phrasing and lyrical twists quickly dispels that notion.

The second disc is a more personally curated collection of trio takes on vintage pop works by Bob Dylan, George Harrison and early Fleetwood Mac guitarist Danny Kirwan, among others. On first listen, the collar grabber of the bunch is a version of the “Goldfinger†theme that pares down John Barry’s orchestral might to a tough-knuckled but melodically faithful brawl that is very much rock ‘n’ roll. You can almost see James Bond and Odd Job going at each other as the groove grows.

Then the last word oozes in – a version of the album’s title tune, a 1972 radio hit by the British pop band Badfinger that completely departs from any musical strategy the album had previously followed.

The sounds enter like distant sirens – echoing at first before gathering into an orchestral ambience that is alternately ominous and warm. The music continues to move in a circular pattern, growing more spacious and intense the closer it gets. Once it formally arrives, the wash of guitar chimes with a thundering intent that surrounds you. Then, as the cyclone passes, tossing one last sonic cry at us in its wake, the tune and the album fade to black.

Somewhere, in that rich, layered fascination, the chorus melody of the Pete Ham-composed tune is offered, but it exists only as a brief wisp of a soundscape that quickly sheds its form before leaping into the squall.

“I had no intention of actually covering that tune,†said a slightly jet-lagged Monder by phone the day after arriving back in New York, following a few weeks of concerts and master classes in Europe. “I was at the end of this session and just wanted to play some random ambient music.

“My guitar broke right at the end of the session. This was during one of the trio sessions for the album. It was no longer functional by the end of the day, so I borrowed what was almost like a toy guitar in the studio. It was like a miniature Les Paul. But I was just determined to do some ambient music as a counterbalance to all the trio tracks we had recorded. I did that thing of turning all my equipment up to ten and then just kind of went for it.

“In the spur of the moment, that melody occurred to me. I’ve played that tune before in a trio setting, so I knew it. But I never thought I would do it like this. I just figured if I could include the melody, it would justify all this being on the record. It would be another cover tune. Technically.â€

Second fiddle

Monder, who is heading to Lexington for a solo concert that will serve as the November presentation of the Origins Jazz Series, has been a highly prolific and respected member of the vast New York City jazz community for over three decades as both a leader and sideman. He has recorded with scores of jazz luminaries, including Grammy-winning orchestrator Maria Schneider (with whom he still collaborates), saxophonist Donny McCaslin and the profoundly influential drummer and bandleader Paul Motian.

While guitar was not Monder’s first instrument, it was the first one that truly spoke to him.

“I took up violin after my dad,†Monder said. “He was an amateur player. I never really enjoyed violin very much, though. It was like a duty. Then I found a classical guitar, an inexpensive classical guitar, in my parent’s closet. It was much less uncomfortable to play than the violin, so I gravitated to the guitar more and more. I only found out recently that the reason my parents even had a guitar was that my mother was taking classical lessons while she was pregnant with me. I must have been hearing that music even then.â€

Jazz records by guitarists like Barney Kessel (especially “Soaring,†a briskly paced 1976 trio album devoted primarily to standards) and Jim Hall (the exquisite trio record “Live!†from 1975) helped establish a musical vocabulary. But it was a vanguard work from the preceding decade, John Coltrane’s immortal “A Love Supreme,†that got Monder digging past the groove.

“That was a big one,†he said. “‘A Love Supreme’ really made me decide that I needed to dive into the mystery of jazz. I may have come to jazz anyway. When I decided to formally start taking guitar lessons, I was studying from a jazz teacher because that was the teacher that was available. It wasn’t like I necessarily wanted to take jazz lessons. But I grew to love the music itself. I enjoyed the challenge of it.â€

Few artists, though, had greater impact in the development of Monder’s musical voice than the great Motian. Infatuated with records by the drummer’s famed trio (with guitarist Bill Frisell and saxophonist Joe Lovano) and his equally lauded quintet (which added a second saxophonist, Billy Drewes, along with bassist Ed Schuller to the trio roster), Monder would eventually join one of Motian’s numerous bands to record three albums between 2001 and 2006.

“Paul Motian started helping my voice long before I ever met him. His first quintet record, ‘Psalm’ (from 1982), was just a total sound world that was unprecedented. If you listen, all of his records have that personal element to it. It’s hard to pin down, but they all sound like Paul Motian records. Even with completely different personnel, everyone is in tune with the sound he has and works towards realizing it.â€

Bowie and Blackstar

While New York has always been a jazz metropolis, it also became a land of self-imposed exile for one of rock music’s most daring journeymen. In 2015, with no interest in living the rock daydream any further, David Bowie scoured the city’s music haunts with the idea of making a new recording aided by jazz musicians. The songs he had composed for the album were still largely pop in design, but were executed with more of a hybrid sound. Bowie had just come off recording a single with Maria Schneider’s orchestra that led to the enlistment of Donny McCaslin. That, in turn, brought Monder to the recording sessions that gave us “Blackstar.†And that, unbeknownst to all parties involved with its making, would be Bowie’s final studio album. The rock titan died on January 10, 2016 – two days after the release of “Blackstar.â€

“The tunes David wrote were very specific with a very clear vision of what he wanted,†Monder said. “At the same time, they were easy to adapt to. It never felt like I had to step into somebody’s else ideas. “When I say ‘specific,’ I guess I meant there weren’t that many ways to interpret the parts, but I still had a lot of freedom in how I was able to add things. Also, Tony Visconti (Bowie’s longtime producer) had lots of ideas.

“There was one day where I went in the studio without the other studio musicians and we came up with parts for almost all of the tunes I was involved with. I had free reign to add layer upon layer. If it worked, great. If it didn’t, we would just throw it out.â€

So for a full day, it was just Visconti in the studio with Monder?

“Yes. And David.â€

A studio day alongside David Bowie and Tony Visconti? Seriously? How enviable a work environment was that?

“It was a lot of fun.â€

What stands as a colossal understatement is indicative of the earnest soft sell Monder gives his music. From the far-ranging stylistic reach of “Day After Day†to the career victory lap that was “Blackstar,†his playing speaks for itself in a manner that welcomes anyone mindful of musical tradition but with ears open enough to not be anchored to it.

“You know, I have no idea how many people have heard my music or what they think of it. I get enough feedback to feel like I’m reaching a few people and that’s fine. If nobody responded, that would be a problem. But if I can reach just a few people where the music really means something to them, then that’s very gratifying.â€

Ben Monder performs at 7:30 p.m. on November 22 at the Lexington Friends Meeting House (Quakers), 649 Price Ave. Tickets are $20 at originsjazz.org.

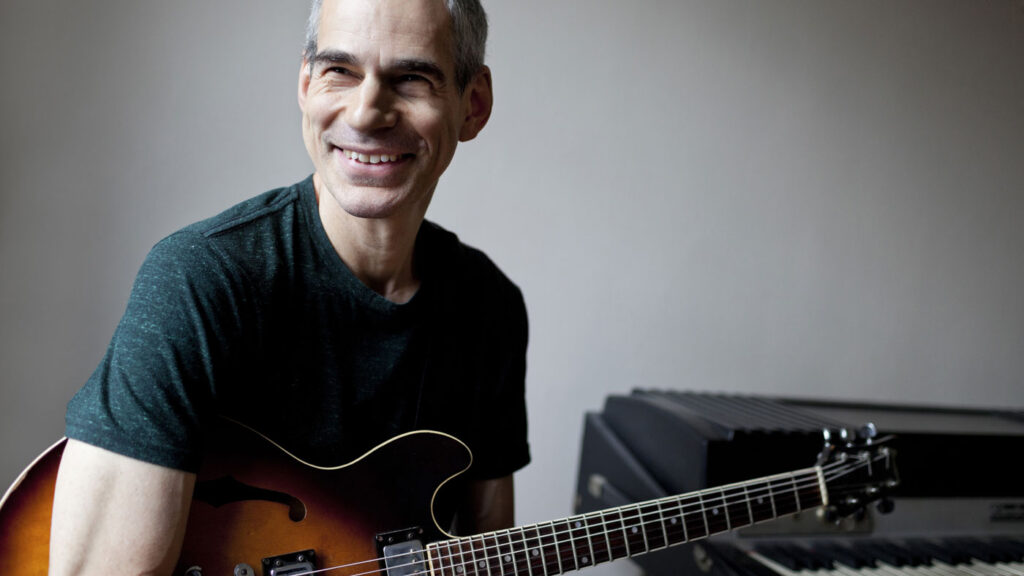

Title Image Photo Credit: Ben Monder by John Rogers