In his Rooftop Soliloquy, Roman Payne states that “All forms of madness, bizarre habits, awkwardness in society, general clumsiness, are justified in the person who creates good art.” Collage and assemblage artist Carleton Wing could take umbrage to this statement but I doubt that he would. When he began making art in the early 1980s, he considered himself an introvert, a shy person with low self-esteem and his art was a safe way for him to assert himself quietly.

Wing is no stranger to the Lexington arts scene where he owned and operated Wingspan Gallery for several years on the corner of Jefferson and Second Street. He sold the gallery six years ago after being diagnosed with leukemia and his only option for survival (20 percent) was a bone marrow transplant. Facing better odds (70 percent) in Florida than in Kentucky, he moved to Tampa where he received a stem cell transplant from a 20-year-old male donor living in Germany. Now back in Lexington, his life has undergone a transformation and his art a transfiguration. Both speak the unspeakable. They shine.

Wing creates his collages and assemblages by “removing familiar images and objects from their original context and rearranging them to illustrate a new notion or idea.” Although his subject matter is serious—gender, religion, war, politics, and class, he often uses satirical titles and humor to further engage his viewers, to make them think and maybe walk away with a smile on their face.

The Cownolfini Wedding, a take-off of Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Wedding, is prime beef. George Orwell’s Animal Farm came to mind when I first saw it. The pigs, Snowball, Napoleon, and Squealer may be missing from the scene but Animalism still rules the day. The period garb of the two central figures is borrowed directly from van Eyck, and Wing’s crafty placement of the mirror on the tree not only reflects the rear-view image of the original painting but also serves as a reminder that we occasionally need to take a closer look at ourselves—even hindsight will do.

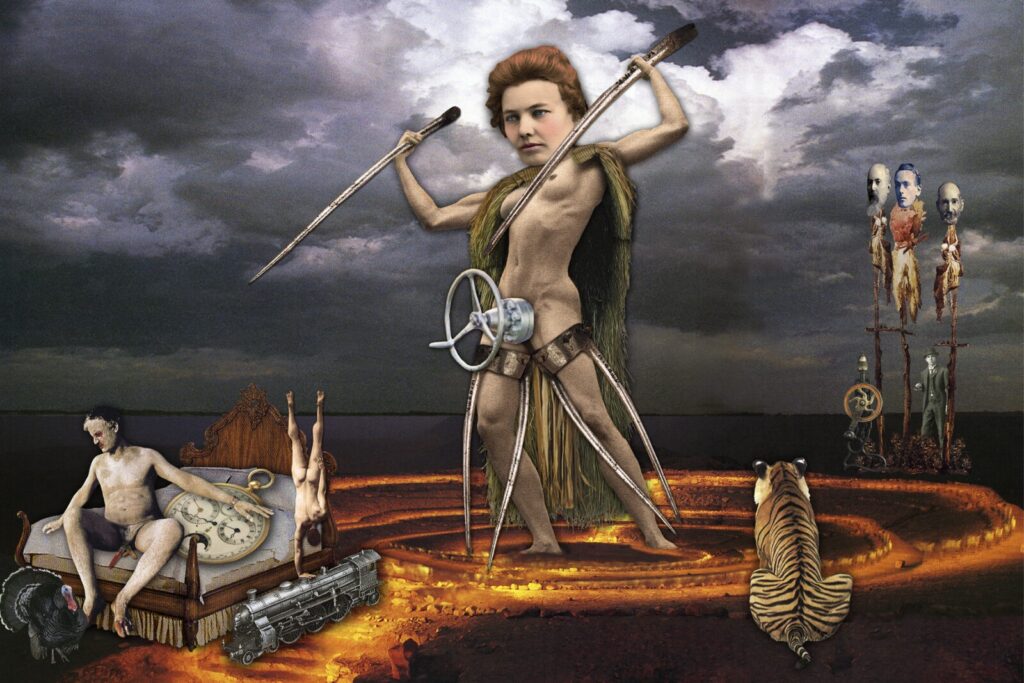

Unlike the bride in Cownolfini, Katrina is not the marrying kind. A hurricane of a woman, she is more like Brunnehilda who, in myth, could be approached only by a man able to surpass her in strength. Wing’s title provides levity and perspective to a perplexing and unsettling work because it imposes a different order on our preconceived notions of reality and sexuality. It is ambiguous and symbolic; it is the surreal inner voice of a bizarre dream.

Wing has a definite kinship with artists like Salvador Dali and Renne Magritte, contending that surrealism can actually bring us closer to reality because it mimics the contradictions and absurdities of the “real” world. And there is method to his madness. Had he given this piece a different title such as The Lady or the Tiger, it would have altered the narrative and the way we look at it.

At the outset of his career 35 years ago, Wing relied on countless images from glossy magazines such as National Geographic, Smithsonian, and Architectural Digest for his constructions. However, the translucent multi-layering effect that characterizes his more recent work was not possible with opaque paper cut-outs. The Internet, Adobe, and archival quality digital printing now provide him with endless resources and creative possibilities, bringing his story-telling to new level.

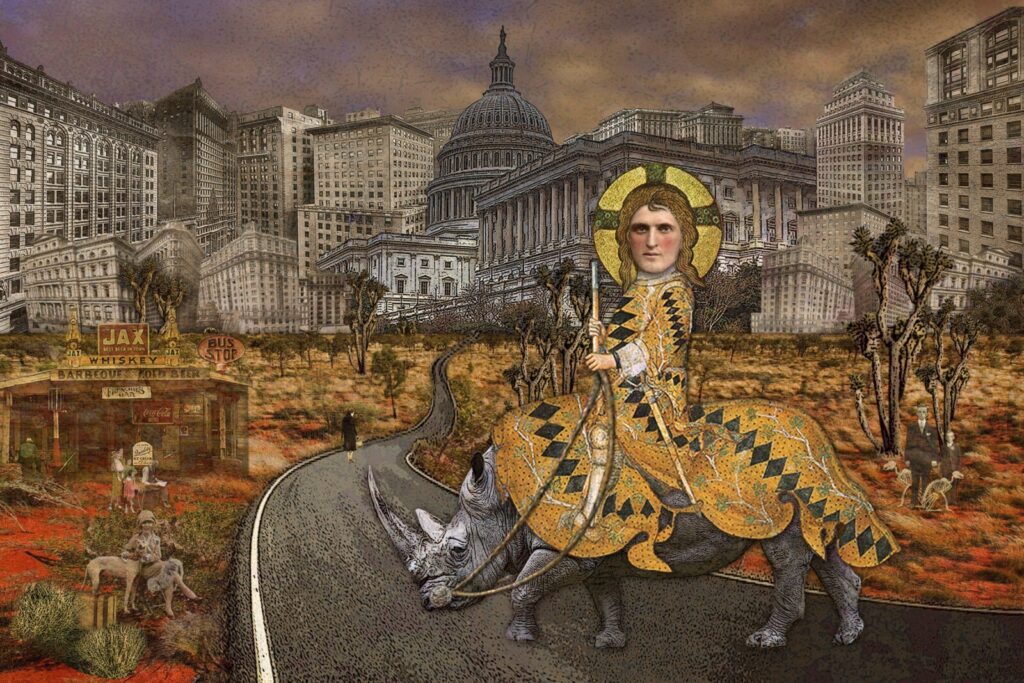

So for Wing, making art is about making choices and then seeing where it leads. His process begins with a single image or object that interests him and then he subconsciously adds other images until he discovers what he is trying to say or until a story emerges, at which point he consciously takes control and works with intent based on how he wants the narrative to unfold as in Jesus Wanders.

Here, Wing brings the Temptation of Christ into the 21st century and Jesus is not exactly slouching toward Bethlehem. He sits upright on a humble beast that travels slightly faster than the speed of a turtle, so he will have plenty of time to absorb the wilderness of modern civilization. It is a complex composition with a penetrating sense of perspective and perception.

The desert is dotted with vignettes, each with its own story. Is that Mary Magdalene sitting there in the lower left with her greyhound? Every line and object, particularly the road and buildings, contribute to the visual depth of the image except for the decorative figure of Christ on the rhinoceros. It is flat, non-dimensional, and stops the eye before it can wander any farther into the landscape. He stares directly at us perhaps leaving us with that single all-important question: What will (not would) Jesus do? I suspect he may stop in at Jax’s for a round with the locals before he heads into town.

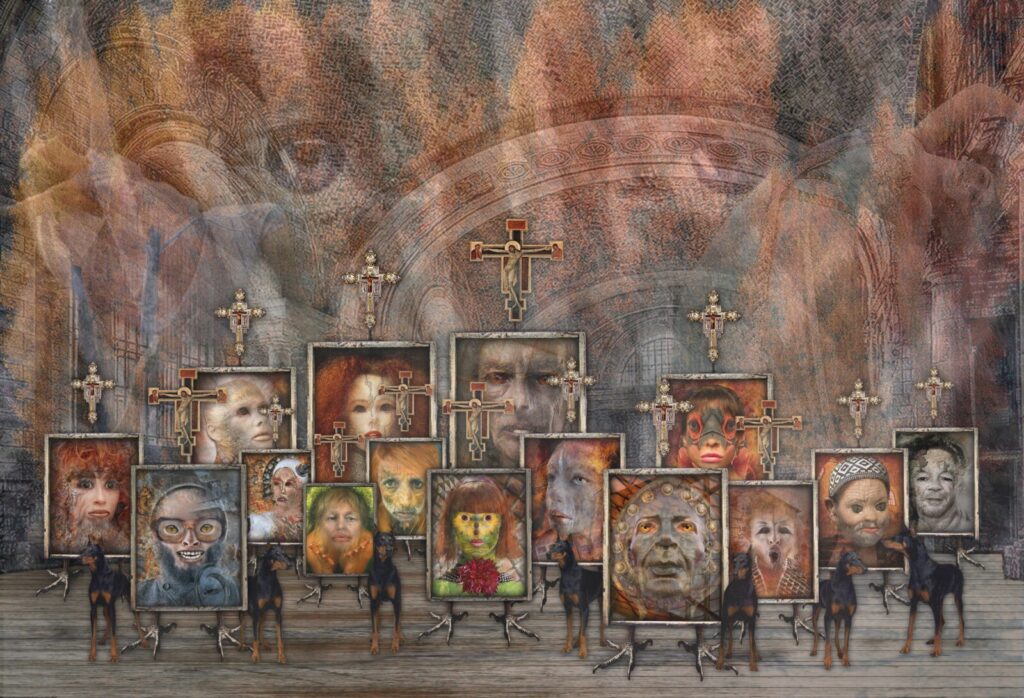

But In the Great Hall poses a different question—one of self-examination. Evoking consternation rather than a smile, it demonstrates Wing’s power to draw in viewers with his process of digitally layering multiple images with such translucency that it is next to impossible to feel you are looking at a single work of art. From the dogs guarding the chicken-footed framed faces that haunt the foreground and the diaphanous swooning females on each side of the background to the pair of eyes overseeing all, the artist presents an allegorical narrative on human nature—we, too, get to make choices.

The rather stern Miss Sturgehill, however, appears to be propelled by a lot of confidence and few regrets. Besides never having lost a road rally, she never misses a photo op either. Wing’s wit, sarcasm, and humor come to the fore in this collage and, being a cat lover, I like to think it began with the single image of the devoted and fearless feline, Mr. Whiskers.

In most of Wing’s collages, as apparent in Miss Sturgehill and Christopher’s Pastime, the heads are a bit too big for the bodies; the size of various objects are not in direct proportion to others far or near, and the perspective, in general, is a little off-kilter. No, you are not suffering from Alice in Wonderland syndrome (AiWS), but you are experiencing Wing’s playful Lewis Carroll effect where both the familiar and unfamiliar are distorted to make us rethink what we think we see or know—or to simply make up our own stories.

Wing embarks on a similar journey with his assemblages, beginning with a single object and then improvising until it takes a form that dictates what he should do next. His Warrior Turtle began with a turtle shell, a doll’s head mold, and a pair of bronzed baby shoes. The rest came from whatever he had on hand that knew it belonged to the warrior.

The codpiece is actually a corn husker; the arms, forks; the weapons, a spear and a kosh; and the headgear, mangrove seed pods. The pieces of leather overlapping the shoulders, the leopard skin fabric, the beads, and the iconic crosses strengthen the ceremonial primitive spirit of this warrior king.

The back of the warrior is flanked with seashells and adorned with a deer’s tail. The anklets which look like chainmail are made from gutter guard. I think you get the point. Question: When is a potato peeler not a potato peeler? Answer: When it gets into the hands of Carleton Wing.

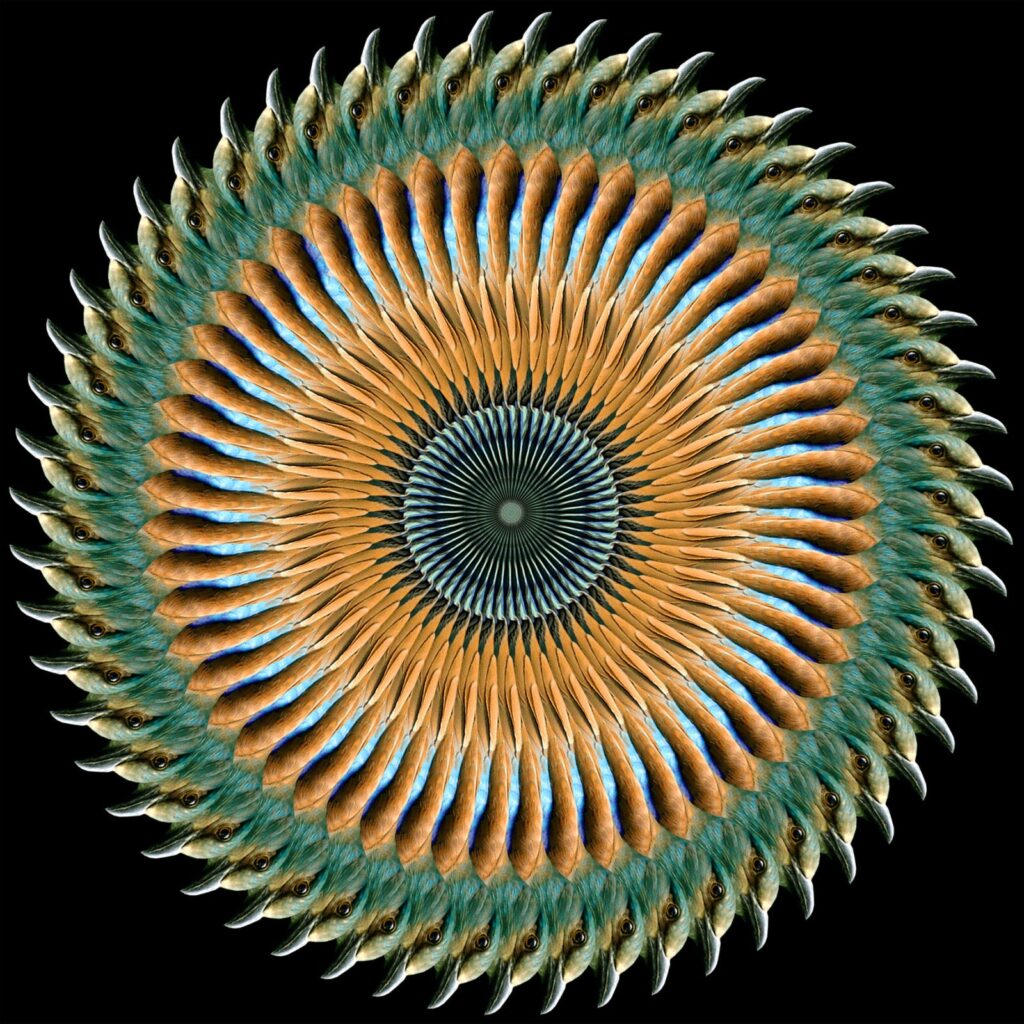

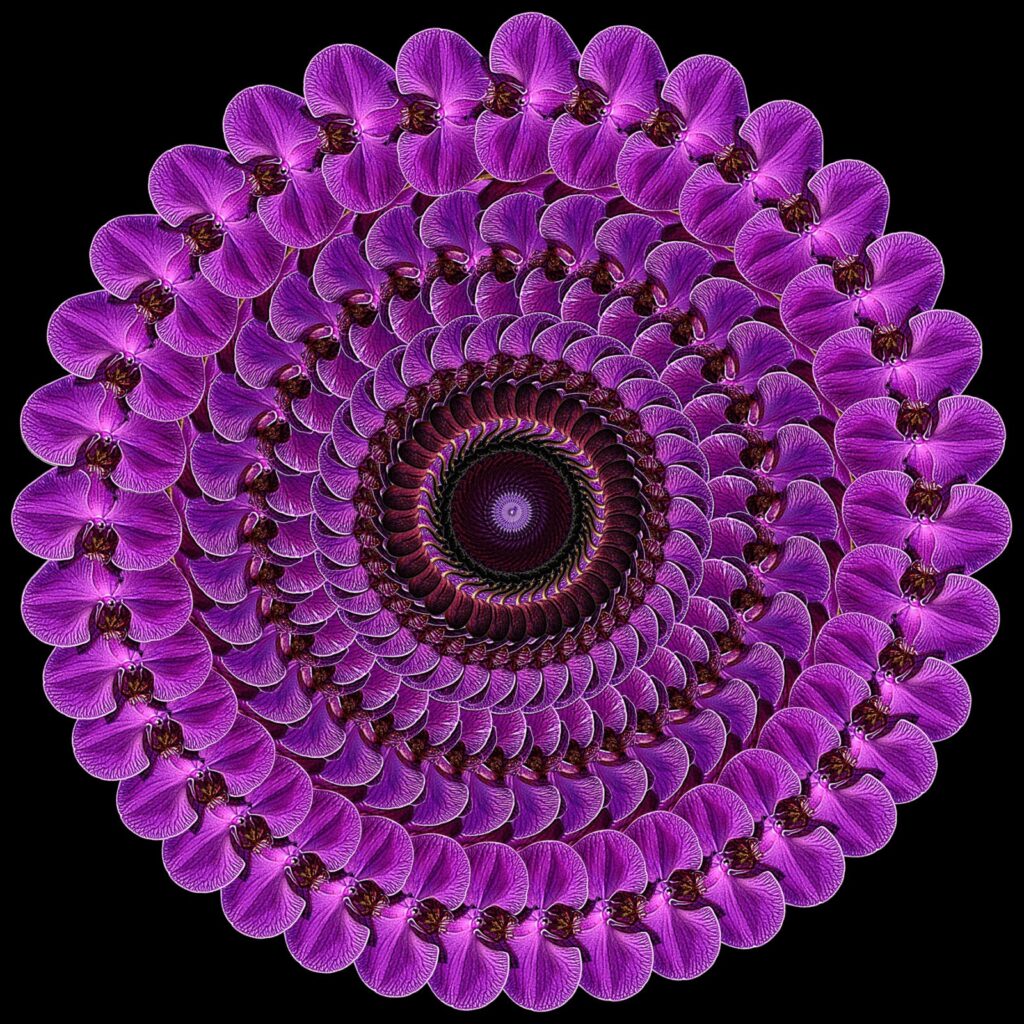

Two years into recovery from his stem cell transplant Wing came back to his drawing board and it renewed his spirit, aided his healing, and improved his outlook on life. His recent collages of secular mandalas, 10 of which now hang in the Markey Cancer Center, further demonstrate to us an artist who sees the infinite in the finite, who sees many worlds within the one we all share.

These mandalas, geometric figures that represent the universe, also signify our search for completeness and self-unity. They have no beginning and no end. The patterns and designs are as infinite as those of the snowflake and as limitless as our imagination when we are not afraid to open our eyes. This is the perspicacity Wing shares with us through amazing works of art such as Bee Eater and Orchid.

I had some questions for Wing:

And…

Wing has two upcoming shows. The first, Short Stories from the Near Side, at the Carnegie Center’s newly renovated Skydome – 251 West Second St. (859-254-4175), opens on Friday, March 16 with a Gallery Hop reception from 5-8 pm, and closes on May 14, 2018.

The second, Sharing Time and Space, an exhibition of his Mandalas in a duo show at M.S. Rezny Studio/Gallery – 903 Manchester St. (859-252-4647), runs from April 10 through May 26, 2018. An artist’s talk is scheduled on May 12 from 11:00 am – 12:30 pm, and a closing Gallery Hop reception 5-8 pm on May 18, 2018.

(All images courtesy of the artist)