Institute 193 is an intimate place; it is a small, one-room storefront gallery space that pulls viewers in from Lexington’s Limestone Street for a different kind of consumption than they might find in the neighboring bars, restaurants, and coffee shops. The intimacy makes this venue the perfect site to view painter Amy Pleasant’s work, now on view in the exhibition “Someone Before You.†The show is simply arranged, comprised of a handful of drawings and ceramic sculptures alongside a single painting. Yet the works allude to the highly prolific nature of Pleasant’s practice, which is further affirmed in the companion artist’s book, The Messenger’s Mouth was Heavy. The proximity to the work in both the space and in the book offer an opportunity for the viewer to deeply consider how and what each work communicates.Â

Amy Pleasant’s use of minimal and reduced forms in her paintings, drawings, and sculptural works evoke questions of symbolism and legibility. The flattened and monochromatic surfaces of the forms she creates remove many of the elements necessary for signification, yet the works remain legible as bodies due to the subtlest inclusion of the curve of a neck, the curve of a knee, or the point of a nipple. At the same time, just as these tiny hints suggest a body, the incompleteness of that form – due to the absence of heads, torsos, and a variety of appendages – decouples the notion of the body from any specific individual, rendering abstract a corpus that more frequently denotes a particular identity.Â

The questions of legibility are clearly manifest in her drawings and paintings, four of which occupy the gallery walls in this show. Her serial Repose drawings consist of a monochromatic disembodied black torso on a faintly grey background. Yet because these forms are so heavily uniform in color and the various other bodily elements are either removed, such as the head and neck, or are completely obscured, like the hands, their reference to the human body must be inferred from the scantest of evidence. And yet, it is still remarkably clear from the way Pleasant outlines the curve of the chest, the shoulder, and the biceps, and from imperfect triangle formed by the bending of the elbow in these three works, that these are, unquestionably, bodies.Â

The abstraction of these forms – specifically the absence of shading, contours, and modeling so often used to render in two dimensions the curvature of our three-dimensional figures – connects them to a broader history of abstract painting in general. Pleasant uses the allusion of the body to explore the implications of color and the painterly gesture, aligning her work with a broader corpus of abstract painters, drawing on the legacy of artists like Willem and Elaine de Kooning. At the same time, the gestures of Pleasant’s figures, particularly the reclined feminine torsos that populate so much of her work, call to mind the canonical figuration of the female nude dating back to the Renaissance. As such, her works read as a part of two distinct yet interrelated traditions in painting, but she does not engage in either of them completely, since her pieces are not complete abstractions, nor are the completed nudes. The fragmentary nature of her forms, as well as their inclusion of minimal signifiers, thus raises the question: what is the minimum of information that we need as viewers to understand a work?Â

This exploration of signification is also apparent in her sculptural pieces. Like her drawings and painting, these works are also comprised of monochromatic disembodied corporeal forms: torsos, necks, shoulders, and arms. And similar to her other body of work, these pieces play with both the history of figurative art as well as that of abstraction; their paired down geometry is reminiscent of the abstract sculptures of artists like Louise Nevelson, Louise Bourgeois, David Smith, and Anne Truitt, yet the allusion to the body calls to mind the longer history of sculpture from the curvature of Bernini and Michelangelo’s expressive marbles to the solidity of Greek bronzes.Â

Yet the sculptural work, more so than the paintings and drawings, engages with the organic nature of these shapes due to the materiality. Sculpted from clay and resting atop custom wood plinths, these works remind us that the materiality of the human body is not so distinct from the environment around us. Moreover, the malleability of clay and its eventual coalescence into a single shape parallels the journey of the human body as it transforms over time into an eventual final body, one that will eventually return to dust. This rumination on the body is made possible because of Pleasant’s fragmentation thereof. In focusing in and abstracting specific elements of the human form, we are able to consider in greater depth what a body is and how it ultimately exists within the world. As such, these works demand the kind of intimacy that Institute 193 provides for them. Arranged in this close space, we as audience members can approach each piece and consider Pleasant’s fixation on each form.Â

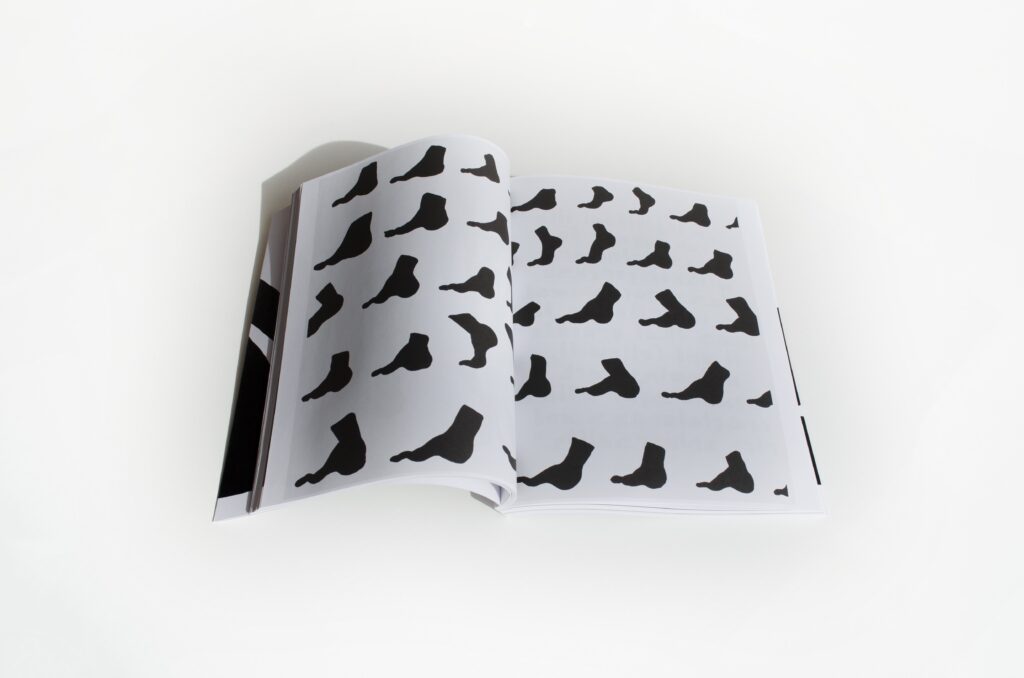

An intimate engagement with Pleasant’s rumination on the body is further facilitated through the book The Messenger’s Mouth was Heavy, published by Institute 193 to accompany this show. Whereas the exhibition invites the viewer to consider the main ideas of Pleasant’s practice by closely reading a few pieces, the book provides a more intimate understanding of the prolific volume of Pleasant’s works. Page after page of this volume is littered with images of monochromatic body parts. Whereas the works in the exhibition largely focus on a single form, many of the images replicated in the book involve numerous iterations of the body on a single page, illustrating the hyper-focused nature of Pleasant’s practice, both literally and figuratively. Moreover, the medium of the book facilitates a closer reading of Pleasant’s work, as we are provided innumerable opportunities to view and return to each work, not to mention the physical proximity that books, as objects, allow in a way that painting, drawing, and sculpture do not. Â

Issues of legibility are also present in the book and are made even more apparent through the translation of her figures into an actual font, used to title essays and transcribe specific quotes throughout the volume. As such, this volume demonstrates another level of Pleasant’s engagement with the question of signification; not only are her forms both abstract and bodily, they are also representational and verbal, challenging us as viewers to read them in several distinct yet interrelated ways.Â

On the whole, in both the exhibition “Someone Before You†and the book, His Messenger’s Mouth was Heavy, we are provided an opportunity to ruminate on simple forms, and in so doing consider the significance and symbolism therein. Â