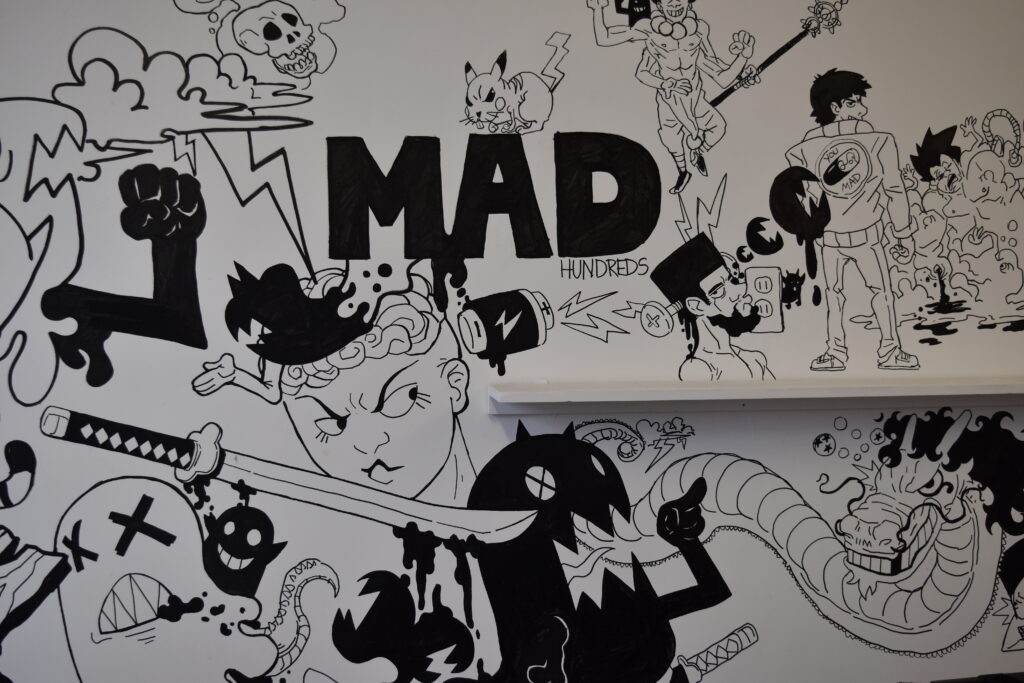

Artist Bryce Oquaye’s studio is a study in contrast. Located in the Lexington Art League’s elegant and historic Loudon House, the artwork that fills it is anything but. One wall is his cool-down board, a spontaneous collection of superheroes and monsters with a ninja and dragon thrown in for good measure. “It is where I stretch myself as an artist, my creative yoga,†says the illustrator, sequential artist, and animator.

This juxtaposition is fully intentional, the product of both his own search for studio space as he launched a freelance business and of the Art League’s goals to support diverse local artists working in a range of media. In discussions, the two discovered common goals and a shared sense of mission. Oquaye joined this summer as an artist in residence.

Oquaye often finds himself living in an in-between place creatively, forced to defend the legitimacy of comics as both art and literature. He knows many don’t hold it on the same level as fine art, but contends he has spent much time and energy honing his craft, aiming for the 10,000 hours of experience that writer Malcolm Gladwell says is required for mastery.

Local live shows have helped build a bridge for people. “When they see creators working right there, it gives them a different level of appreciation,†he says. “When they see the time and energy we put into it, it elevates comics as art.â€

It is more specific and complex than people might realize. Comic artists are not just drawing pictures; they are translating the visual representation of a full narrative. “The visual is not a crutch; the narrative is there,†says Oquaye. “Good writing is good writing.â€

The format of comics gives an inroad to explore difficult subjects with unsuspecting readers. Not only were comic books the first way Oquaye learned about string theory, but they also made thinking about sensitive topics like racism more palatable to him as a young reader. “Comics mesmerize you with visuals and give a message all at the same time,†he says. “One of my favorite things about comics is they entertain with substance, but without preaching.â€

Mind you, Oquaye’s messages are subtle, hidden among monsters, superheroes, and action-packed storylines. His current project, a graphic novel called “Kaiju Effect,†illustrates the way his message underlies the narrative action. The tale centers around a Black police officer. Kaiju fights with monsters and saves the city. He also wrestles with his identity and the difficulty of working in a career that has a history of brutality to his own people. The story speaks to our differences but shines a light on one of Oquaye’s favorite themes – how connected we all truly are.

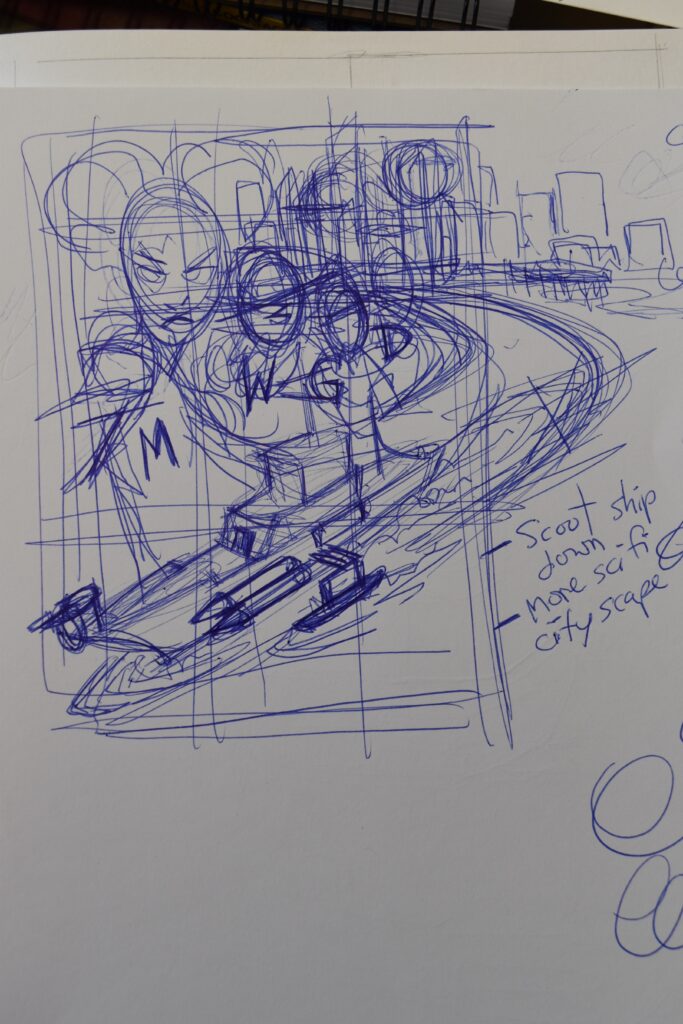

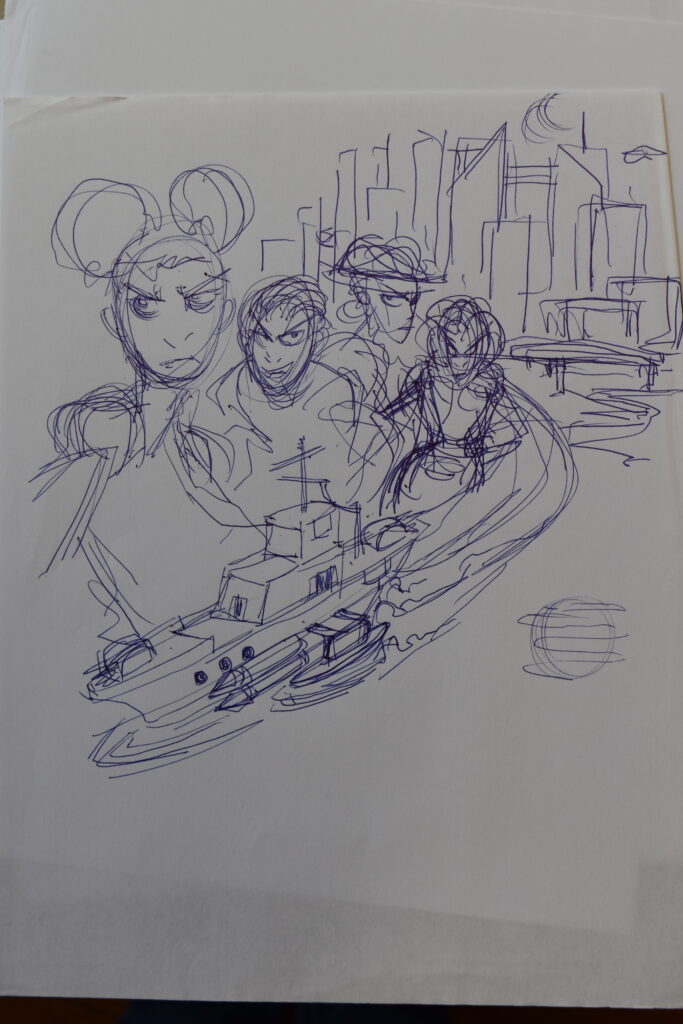

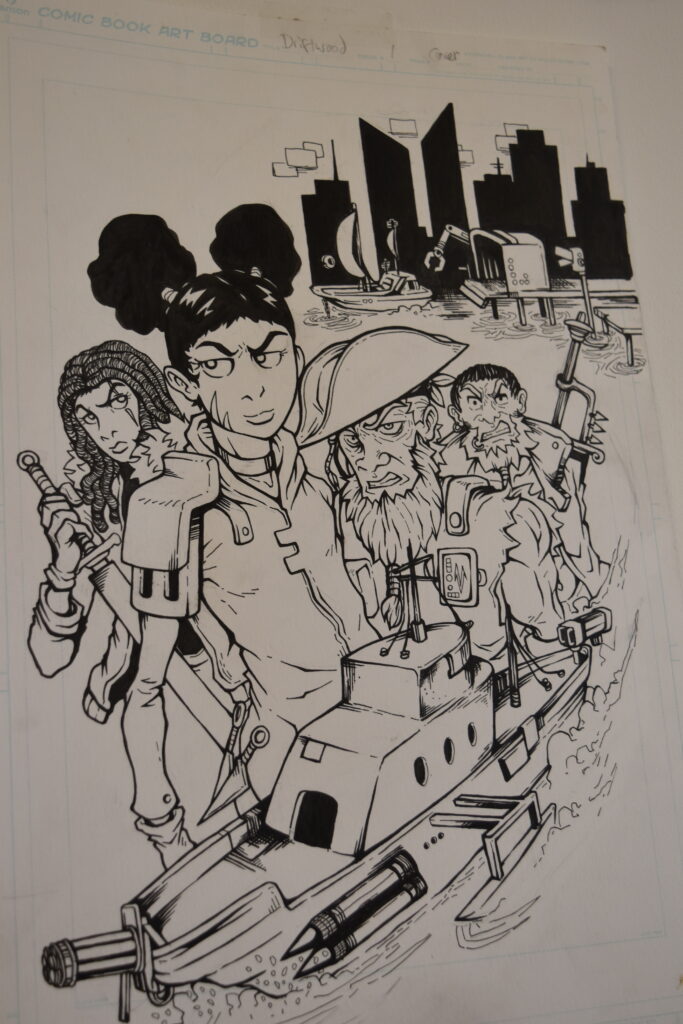

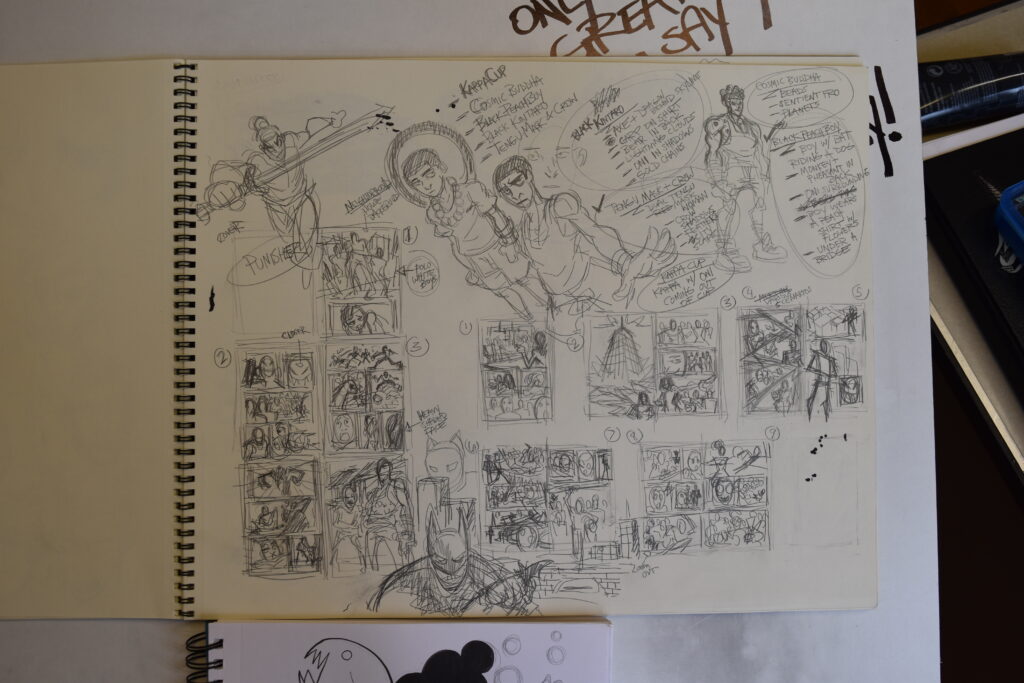

Oquaye’s stories begin as concept sketches, storyboards, and panel layouts. His world-building and narrative preparation are extensive. “The storyboards give me a nice skeleton, and by laying out the environment I build the sandbox first,†he explains.

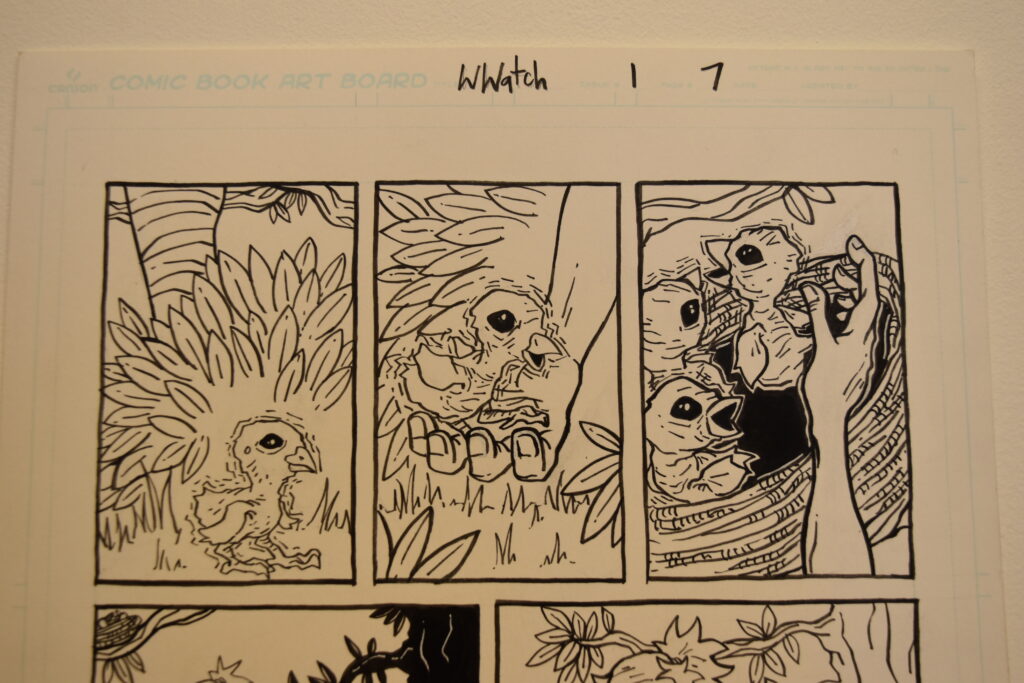

While technology is an integral part of Oquaye’s art, most of the work begins with him putting pencil to paper. Some pieces are completely designed on paper and then scanned in, while others he transfers to his iPad earlier for completion.

“I use whatever will get the look I want – pen and paper or straight digital,†he says. “Some techniques are easier in the traditional medium, like dry brushing. I mix and match.â€

For “Kaiju Effect,†he created a pitch packet, a proof of concept, to market the idea to publishers. Images from the packet hang on his studio wall, inspiring him and working themselves into his thoughts. He plans Kaiju as the longest comic he has ever written. Styled in Manga format, each of the two volumes will be 200-250 pages long. As he completes chapters, he will publish them on UE Comix, a Black-owned free-access webcomic platform.

Though Oquaye started drawing when very young and grew up in the comics heyday of the 1990’s, he backed off of art as a young adult, discouraged by those who said Black people don’t draw comics. His confidence grew when he found a global connection to other creators online. “I fell into a network of amazing Black artists, all jumping in at the same time,†he says. “Seeing others step out of their comfort zone pushed me forward.â€

For six years, Oquaye served at a Lexington restaurant while building up his portfolio between shifts. He saved money so he could travel to Chicago and have his work professionally reviewed. It was a turning point that solidified his commitment.

“The artist I consulted basically said my portfolio was trash,†says Oquaye. “I had to ask myself, ‘How much do you believe in what you are doing?’ I knew if I was serious about it, I was going to have to fail a few times.â€

Determined, Oquaye went back to the drawing board and kept consulting artists about his work. Finding a family of like-minded Lexington artists through a collective called Six Bomb Boards helped him take huge strides forward. He claims membership in the group is one of the most important things in his creative life.

He teamed up with another group member and launched a successful Kickstarter for a collaborative comic called “Warden’s Watch.†Through the group’s encouragement and influence, he flexed his creative muscles through graphic arts positions at FedEx and local sign shops.

Then Chef Dan Wu opened Atomic Ramen and hired Oquaye to paint a large mural in the shop. “Lexington is an artsy city that supports creativity,†he says. “That mural put me in front of a lot of people and led them to my artwork.†Not long after, he established his independent art business. Alongside his comics work, he focuses on graphic arts and animation. He develops logos for organizations, and designs album covers and music videos for Hip Hop artists.

Looking ahead, one of Oquaye’s hopes is to pay forward the mentoring opportunities he received to other young creators. He dreams of a creativity-focused community center that empowers kids, especially minority ones, to counteract negative messages and foster healthy ways to process difficult circumstances. In working with schools and libraries, he is the first Black artist some of the kids have ever seen. “I want to let them know their stories are important and that they can be creative,†he says.

The next year holds a lot for Oquaye. Along with his Kaiju graphic novel, Loudon House will host his first solo show. He is excited to try his hand at creating directly on canvas, preparing new work that combines an exploration of world religions with graffiti-style street art.

As Oquaye continues to mature artistically, certain elements of his work will remain constant: pushing genres, challenging perceptions, and telling fun visual stories with substance.

All photos courtesy of the author.