In December 2019, I met with KÅan Jeff Baysa, the elected presider over UnderMain’s fourth running of the Critical Mass Series (CMIV) as the incoming Critic-in-Residence (CIR) with the Great Meadows Foundation (GMF). As we sat in a window seat at Nyonya in Manhattan’s NoLita neighborhood, I shared details about UnderMain and why the Critical Mass Series was founded, primarily as an effort to bring a multitude of talent together in critical discourse about the role of contemporary art in the region.

I explained my original concerns about the lack of critical writing and the ongoing battle against stereotypical notions of Kentucky as a backwater, and that Critical Mass had become my passion. Over the last three years, I’d reached out to various leaders in our community and worked with interns, artists, and writers to include their voices. UnderMain funded the program in its entirety. Then, in 2019, The Great Meadows Foundation recognized our efforts and a common goal for the two organizations: Both were intent on developing Kentucky’s collective voice in the world of contemporary art and, as a result, GMF granted funding to UnderMain to support CMIV, CMV, and CMVI.

KÅan had visited Kentucky before, and from the range of topics that flowed from appetizer to entree to tea, I knew CMIV would succeed on a grander scale than in years past. KÅan’s approach was clearly global; together we began weaving an even larger tapestry.

From our meeting, two topics remained at the forefront of my mind: First, KÅan’s comments after speaking with Fred Wilson about the museological approach underpinning his installation at the Maryland Historical Society titled Mining the Museum – namely to challenge all narratives presented to us – and second, KÅan’s intrigue with The Rubin Museum, which I later toured for the first time. This was a remarkable collection of contemporary works in conversation with the collection of Himalayan art. These talking points were harbingers of what would develop in the coming months with KÅan leading the 2020 Critical Mass Series – open discourse was at the center of both.

The Wilson and Rubin discussions would also lead to an exhibition proposal that UnderMain agreed to mount in partnership with 21c Museum Hotel and the GMF, Icon Interventions, which KÅan curated and discusses further in the interview conducted with him here.

KÅan later joked that our lunch had ranged from ‘cabbages to kings’ and that was just the beginning. Under usual circumstances, he was to spend approximately eighty hours in Kentucky artists’ studios and help raise the level of critical discourse among artists in the region.

In March 2020, the circumstance was far from usual, and while the pandemic robbed us all of what we might have done together, what we could have learned first hand from KÅan Jeff Baysa, and what outcomes we may have been able to build upon for 2021, it also meant the residency spanned four months and influenced many more conversations than we had anticipated, much of which is discussed in this in-depth interview.

KÅan requested that I include the caveat that his findings revealed in this interview are in no way comprehensive of the Kentucky art scene, that all errors of omissions are his alone, and that his comments are based on limited observations with mostly personal impressions guiding him.

CH: How many artists did you visit across the state of Kentucky?

KJ: Over the two months (Feb-March 2019) that I was invited to serve as the third Critic-in-Residence (CIR) for the Great Meadows Foundation (GMF), and for the two additional months (April-May) prompted by the advent of the COVID-19, I interfaced with just short of ninety individuals in Kentucky’s creative communities. For the first six weeks these interactions were actual studio visits, then via virtual interviews, successively from the INhouse in New Albany, to a private apartment in NuLu, and then the Speed Mansion in Old Louisville.

CH: How did you determine which artists to include?

KJ: Some groundwork had been laid when I made my first visit to Louisville in 2005. I did a studio visit with Steve Irwin, was introduced to Julien Robson at the Speed Museum, met Ed Hamilton in his studio, visited Zephyr Gallery, and toured 21C in its original location. Fast forward to 2020. In the interim, Steve passed, Swanson Gallery closed, and 21C grew to nine locations, among other changes. As a curator and critic, in the fifteen-year period of living in Honolulu, Los Angeles, and New York City, I wasn’t able to keep track of what was happening in Kentucky contemporary art.

Al Shands and Julien Robson had the foresight to host a dinner with a dozen leaders from Kentucky arts organizations and two large groups of artists. As an icebreaker, I asked individual artists to introduce themselves to the rest of the group. The icebreaker generated conversations between adjacent “strangers,†all of whom were all members of the same creative community but were previously unaware of their neighbors’ roles and contributions. I largely met my goal of meeting every artist present, encouraging each to contact me for a studio visit as Anna helped collate the lists of artists.

It was my first time meeting the group of four women artists funded by GMF to experience the 58th Venice Biennale 2019: Sandra Charles, Toya Northington, Ramona Lindsey, and Lucy Azubuike. As I settled into my role as CIR, I attended openings, panel discussions, poetry slams, and other gatherings. One of the first openings in Louisville I attended was African-American Women: Celebrating Diversity in Art at Kore Gallery, commemorating Black History Month when I was introduced to the artist Elmer Lucille Allen.

At KMAC’s poetry slam Anna introduced me to visual artist Lance Newman who organized the impressive showcase of talent that evening. An invitation by Ramona Lindsey, Program Officer at Hadley Creatives, to conduct critiques offered another opportunity to meet artists. Visiting regional art collectors and viewing their collections was a good way to know works and artists in concentrated forums.

Larry Shapin and Ladonna Nicola focus primarily on collecting and displaying the works of Kentucky artists in their spacious home, and are now planning another structure on the property for art. Gil Holland, who is credited with branding and developing the NuLu and Portland neighborhoods, gave me a virtual walkthrough of his home collection. John Brooks and Erik Eaker generously shared their select private collection with me.

I was privileged to have several walkthroughs of the extensive art collection at Al Shands’ Great Meadows home and grounds. Invitations to private homes for properly socially distanced meals provided additional opportunities to see works by local artists: dinner at gallerist Susan Moremen’s with artist Gaela Ewin, and lunch with the retired pioneer photography educator CJ Pressman and the former zoo curator Marcelle Gianelloni, who have amassed an astounding collection of regional folk art and contemporary photography.

Chris Radtke, one of the founders of Zephyr Gallery, gave a gracious tour of her home, her artwork, and extensive art collection. I was also able to view artworks collected by Henry Heuser, Jr. in the offices of the Community Foundation of Louisville.

CH: What regions of the state did you reach?

KJ: My directive was to visit artists living within the one hundred twenty counties of the Commonwealth of Kentucky and two adjacent counties across the Ohio River in Indiana. I went north to attend a panel discussion at the Kennedy Heights Art Center in Cincinnati featuring Kentucky artists John Brooks and Kiah Celeste. Venturing south to Western University Kentucky in Bowling Green, I saw artists and instructors Yvonne Petkus and Kristina Arnold.

I drove to Nashville where Tiffany Calvert and Josh Azzarella opened their joint exhibition at Tinney Contemporary, east to Morehead State University to visit Melissa and Adam Yungbluth and photographer Robyn Moore. Through the kindness of Alice Gray Stites, Chief Curator and Museum Director, and Nico Jorcino, Director of Museum Design & Planning, of the 21C Museum Hotels, arrangements were made for me to stay at and tour the current shows and collections at 21C locations in Lexington, Nashville, and Cincinnati.

I was fortunate to get in touch with creatives and organizers working near and in Appalachia. With prior affiliations to Appalshop, Lacy Hale and Robert Gipe gave insights into the hardships of surviving as artists and art advocates in the area.

Writers for Affrilachia, Crystal Wilkinson and Frank X Walker gave strong insights into the origins of Black art, craft and literature in Appalachia. I was able to visit the shows: Black Before I Was Born curated by Ashley Cathey at the Roots 101 African-American Museum founded by Lamont Collins; the beautifully installed solo show by Megan Bickel at the Georgetown College Gallery; the handiwork of Danny Seim and the art installed at the Portland Museum; and a chance to meet Daniel Pfalzgraf who curated the work of Eke Alexis in Permanent and Natural at the Carnegie Center in New Albany.

Given the opportunity, I would have further explored lesser-known art venues, researched more black artists and queer artists in Appalachia and visited the artist Julie Baldyga. I had plans for explorations to Paducah further to the west, Whitesburg to the east, and Covington in the north, but the pandemic truncated those travel plans.

CH: What genres were represented by the artists you visited?

KJ: All 2D and 3D genres were well represented, and I was especially interested in works that crossed disciplines and combined platforms, so I specifically reached out to Teddy Abrams, widely acclaimed Music Director of the Louisville Orchestra; Robert Curran, the iconoclastic Artistic Director of the Louisville Ballet, and Matt Wallace, the Director/Facilitator of the Shakespeare Behind Bars program at the Luther Luckett Correctional Complex. In other genres, I approached Edward Taylor in fashion, Amberly Simpson in dance, and Jane Jones, a playwright. Fortunate to be given a tour of the artworks installed in the expansive UK HealthCare Center in Lexington, I am grateful to Jason Akhtarekhavari, the Manager of the UK Arts in HealthCare program.

I also wish to acknowledge the art programs at outdoor sculpture parks that expand the scope of contemporary art experiences for the public, especially for school age youths and for hosting international artist-in-residence programs. I was invited by Jenny Zeller, the Visual Arts Coordinator at Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest to tour artworks installed on the grounds. Besides the wildly popular Forest Giants, especially notable is Earth Measure (2013) the large sculptural installation by Matt Weir. Similarly, Josephine Sculpture Park Director Melanie Van Houten gave me a tour of the installations in the landscape.

Near the entrance is a remarkable installation by Lucy Azubuike whose arc of tall poles presents previews of tree-based pareidolia found in the park and constitutes the basis for exciting discoveries by children. Innovative Louisville exhibition spaces include the exhibition space Houseguest, as well as the front room of the home of artist Megan Bickel and chef Jacob Wilson. Art-related dinners are hosted in that same space. Sheherazade is the converted downstairs garage space of the studio home of Julie Leidner. On a busily trafficked street, the shows are observed through windows in the rollup garage door.

CH: What are some themes or topics that the artists you visited seem to hold in common?

KJ: Identity politics of race, gender, and class are being universally addressed. Artists can be effective catalysts for change, so the crucial issues of segregation, homelessness, opioid addiction, institutionalized incarceration, toxic masculinity, the legacy of slavery, serial exploitation of Appalachia, immigration, and other hot-button topics, could be further explored. Critical discourses are hampered in part by the culture of regimented politeness and lingering segregation. Kentucky is fractured into 120 counties within which there is underrepresentation of Asian-American, LGBTQA, and indigenous artists.

Particularly arresting and poignant, Brianna Harlan’s installation in Skylar Smith’s exhibition Ballot Box, at Louisville Metro Hall, chronicled her grandmother being denied voting because she, on command by an election official, allegedly sang the Star Spangled Banner off-key. I appreciate the energy and dedication that self-taught artist Jaylin Stewart invests in her painted portrait series that she also executes in chalk on city streets. I was not able to experience the powerful poetry and performances of Hannah Drake but we spoke about her forceful enacted oratories on social justice. I was struck by the art of Thaniel Ion Lee that transcends physical restrictions and takes flight in highly detailed drawings, photo self-portraits, fine digital images, and instructional word-images.

CH: Does ‘Kentucky art’ have a distinguishing character of its own?

KJ: Some may look to the KMAC Triennial as an example, but I am not aware of any characteristics that would distinguish works as “Kentucky art.†When I posed the question regarding the existence of a “School of Kentucky Art†and what Kentucky art is known for, the conversation often turned to the crafts in Kentucky, especially art from Appalachia. The institution’s name – Kentucky Museum of Art & Craft – reflects its historical emphasis on craft, and evokes longstanding discussions regarding art and craft.

When conducting a straw poll on “famous Kentucky artists†the names mentioned most often included Ed Hamilton, Keltie Ferris, Letitia Quesenberry, and Steve Irwin. Hamilton is a world-renown sculptor based in Louisville. Ferris, who lives and works in Brooklyn, is known as an artist from Kentucky locally noted for having “made it†by being represented by an established gallery in Manhattan. Quesenberry has also shown in New York, lives and works in Louisville, noted for her work with light installations, and her work with the Louisville Ballet. Irwin was an acclaimed, charismatic, and beloved Louisville artist famous for his hedonistic lifestyle. Undergoing cardiac bypass surgery in his 20s, he bore a precarious cardiac status and died at age 51 of a massive heart attack. Certainly not to the exclusion of other organizations, I acknowledge the significant contributions of the Great Meadows Foundation, the Kentucky Foundation for Women, the insightful leadership of artist director John Brooks at Quappi Projects, and the adept stewardship of Susan Moremen in directing her eponymous gallery. I am grateful to Warhol Grant awardee Paul Michael Brown in Lexington for introducing me to Institute 193 and its mission of championing quality relevant works over commercial viability.

CH: Are there a few artists whose work really stood out?

KJ: I’m very much interested in surprising processes and the novel manipulation of material; I’m totally entranced by the approach that Vian Sora employs to initiate her stunning abstract paintings with evolving figurative references. The scale of her polyptychs approximate immersive experiences. The fabric-based series by Crystal Gregory revolve around her concept of “material interrogation†that involves the astonishing use of cloth in conjunction with glass, pewter, and concrete.

The head of the glass program at the Hite Art Institute of the University of Louisville, Che Rhodes demonstrates his creative mettle of working outside of the mainstream glass studio practice with controlled explosion glass-within-glass pieces.

By layering digital and physical masking, digital printing and painting, a particular series by Tiffany Calvert reads as Dutch still lifes with technologic flourishes.

Having studied traditional Asian ceramic glazing and firing techniques, Ian Pemberton challenges himself by altering the processes from engineering perspectives to produce “relics for the future.†In addition, I like the scaled-up scratched mirror pieces by Jacob Heustis, the repurposing of metal and wood, experimental cast metal work by Andrew Marsh, driven by a personal history of physical trauma and chronic pain and the brilliant epoch-collapsing social commentary collages of Stan Squirewell.

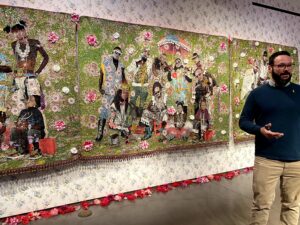

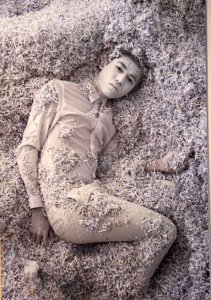

Having taught as Associate Professor in Painting and Mixed Media at the University of Kentucky, Jamaica-born Ebony G. Patterson creates eye-dazzling socially conscious large-scale works that are placed in many collections, including in several of the 21C Museum Hotels. From Cambodia, Vinhay Keo creates self-referential photographs, performances, and installations that embody an important rising immigrant voice. Having completed his studies at the Kentucky College of Art and Design, the talented artist now lives and works in Los Angeles.

Among the several artists that working with fabric, the standout is the quilted work of Penny Sisto for her exquisitely detailed large-scale portraits of select iconic individuals. I’m fascinated with the scope of concepts tackled by Mary Carothers, especially her ambitious encasing an entire car frozen in ice. I was enchanted by my studio visit with Cynthia Norton and her performances as alter ego “Ninnie Noises Nonesuch†of rural Kentucky accompanied by her self-made musical instruments.

I have yet to see the finished sculpture that Maker’s Mark commissioned Matt Weir to create. Over two separate visits totaling nearly hours, I reviewed his tremendous range of works and was particularly impressed with the specialized tools that the artist invented and built for the precision work required to execute Earth Measure and his current commission.

CH: We understand that you were able to connect artists with larger art world experiences. Can you elaborate on those?

KJ: I habitually make individualized recommendations to artists with each encounter. These include suggestions of reference articles, other works of art, and art residencies with whom I am affiliated: Omi International Arts Center, Residency Unlimited, iBiennale, Joshua Treenial (California), Fresh Winds Biennale (Iceland), Kaus Australis (Netherlands), Young Congo Biennale (DR Congo), and other connections. My written recommendations made for the artists of Hadley Creatives were copied and collected by its program officer. As CIR, I was first generously housed at INhouse, in the Silver Hills section of New Albany. I envisioned it as a meeting place for artists. Unfortunately, grand plans for a multisensory dining event fell through at the last minute. On one evening, Julien organized an introductory meeting with members of the critical discourse group Ruckus. The event that I was happiest with was an elaborate meet-and-greet event that centered around the four female artists from Kentucky who were funded by the Great Meadows Foundation to experience the most recent Venice Biennale. I coordinated a potluck BYOB event of ten artists, each of whom was asked to bring a guest. Each person was then expected to share his/her/their work with the group. The happening encouraged lively dinner conversations, enthusiastic discussions of the presentations, and the making of new friends and potential collaborations.

The other large opportunity that was scuttled by the pandemic was Icon Interventions at the 21C Museum Hotel in Lexington. The concept was to have works by Kentucky artists in conversation with works in the then current exhibition Pop Stars!. Supported chiefly by 21C, Great Meadows Foundation, and UnderMain, the associated conference, Critical Mass IV – led by Christine Huskisson – was drawing audiences from New York, Cincinnati, Nashville, and elsewhere. It was a golden opportunity to showcase art by Kentucky artists, introducing them to larger audiences of curators, museum directors, critics, bloggers, and others from outside the state. I offered to support the application of a Kentucky artist with arthrogryposis to a funded position at Omi International Arts Center in upstate New York. An artist with the same condition was invited to the residency program several years ago and I shared that artist’s work with the potential applicant. Another instance was referring Letitia Quesenberry to the career of friend Eric Orr, a California Light and Space artist whose works were previously unknown to her. A further example is putting Mary Carothers, a prior visitor to the Faroe Islands, in conversation with artists Brandur Patursson and his father, well-established artists there. I met the island artist when I served as the Curatorial Advisor for the Fresh Winds Biennale VI in Iceland.

CH: How did the regions’ public/communities compare in terms of engagement and support of artists?

KJ: As a bona fide erstwhile farmer producing the gourmet goat cheese, chevre, I’ve often made the analogy of a healthy art ecosystem with a well balanced milking stool. In a gross oversimplification, the contemporary art world is made up of a several components that are analogized to the legs that support the stability of the stool: producers (artists), consumers (individual collectors, institutions), and facilitators (gallerists, critics, curators, museum directors, nonprofit facility directors, etc) that work between the two. Art activities in Kentucky are centered mainly around the more populous cities of Lexington and Louisville, and towns with colleges and universities with art departments. Kentucky has an imbalance in the components of the art world ecosystem: a pool of talented producers/artists in all disciplines, modest exhibition-promotional-sales sectors, and a limited consumer/collector base. The more “legs†equitable in position and in length, the more stable the entire structure. The ongoing challenge is how to grow the individual and corporate collector bases to support the artist communities, perhaps from younger generations with wealth, innovative concepts, and new definitions of collecting. There is a disproportionate number of exhibition venues for the numbers of artists. Admirably, Quappi Projects, Roots 101 and the Portland Museum are proactively building diverse audiences and constituencies. Real estate developers, architects, and designers should be engaged in this discussion. The dependence of the Kentucky art market as primarily in-house sales-driven should be reassessed. Critical discourse in Kentucky is ably served by organizations like Ruckus and UnderMain, and should be scaled up. The upcoming careers of curators-in-training at the Hite Institute should be encouraged and supported early on in their careers. Most importantly, active conversations between these various components of the Kentucky art ecosystem should be encouraged and sustained rather than being siloed, for that just maintains the status quo.

CH: What steps could/should be taken to strengthen the Kentucky visual arts communities?

KJ: Strive to correct the imbalances as described. This was also answered in part previously. Take initiative. “Chance favors the prepared mind.†– Louis Pasteur. Don’t be shy asking for help. “Not trying guarantees failure 100% of the time.†Take advantage of the resources offered by existing local resources like Great Meadows Foundation, Kentucky Foundation for Women, UnderMain, Louisville Visual Arts, and like organizations. Start with the individual artist. Professional development, available through programs and through personal initiative, is crucial. Artists should be articulate and conversant about their work from a personal perspective and within the larger context of the art world. Read, research, and experiment. Be curious. Satisfy that curiosity. Share resources and knowledge. Form, join, and participate in artist discussion and critique groups, in addition to those in academic settings, of mentors, peers, and juniors is important for personal and professional growth. Become an art collector. It’s not elitist to collect art. Herbert and Dorothy Vogel were civil servants who amassed one of the most important post-1960’s art collections in the U.S. One can start modestly by buying or trading works with other artists. Get to know art dealers and art advisors. Propose an installment plan and/or ask for discount with purchase, as many art dealers are willing to work with collectors. Be mutually supportive. Seek out and attend as many openings, receptions, award ceremonies, campus activities as practical. Introduce yourself to a “new stranger,†an artist you don’t know or whose work you’re unfamiliar with. Discover what you have in common or just make a new friend. Be voracious in looking at art.

If you feel that you’ve seen everything in your town, travel to see exhibitions whenever possible, whether actually or virtually. Proactively invite more people to your studio. If you’ve gone through the “usual suspects†regionally, find out which visiting art persons are around and approach them. Curate an exhibition. Whether solo or group exhibition, the process of mounting an exhibition will be educational. Critique an exhibition. Express yourself. If not for publication with Ruckus or UnderMain, put it on your blog and share it with colleagues. The characteristics of “Southern hospitality†include humility, courtesy, good behavior, modesty, and “knowing one’s place.†Genteel Southern upbringing discourages disparaging one’s neighbor, especially in smaller communities where everyone knows each other’s business, and particularly in the subpopulations of the art world. This is keenly impactful in the subject of critical discourse in Kentucky, where reviews may be perceived as more descriptive than critical, but commendable efforts by organizations like UnderMain and Ruckus are reversing the trend. Surprised to discover that Louisville was among the top ten most segregated cities in the U.S. along with neighboring Nashville and Cincinnati, I learned of Louisville’s notorious “Ninth Street Divide.†Acknowledging its Sisyphean challenge, I encourage and support all measures that promote bidirectional porosity and the ultimate breakdown of this physical and mental barrier. The origin of the name Kentucky as the “dark and bloody ground” is arguably ambiguous, but the double entendre evokes historical and current events of racial and gun violence.

CH: Do you feel that the artists in Kentucky have access to enough outlets (galleries, publications, critical review, collectors) to develop their work to its fullest potential?

KJ: No. But access is not just limited to these outlets, for they are moderated by psychological, socio-economic, temporal factors as well. Notably, direct person-to-person communication is effective, but vastly under-utilized and integral to professional development. Also see prior responses. And Yes. The internet is a vast ocean of information with remarkable potentials for developing access to these outlets. Also see prior responses.

CH: What can Kentucky do to begin a collective conversation (together with the artists from all areas of the state) with the larger world of contemporary artists?

KJ: Collective conversations have already been initiated with organizations like Great Meadows Foundation. By funding artist experiences outside of Kentucky, it has importantly extended and increased the exposure of Kentucky artists to the larger world of contemporary art. Again, I cite the funding of Sandra Charles, Toya Northington, Ramona Lindsey, and Lucy Azubuike to the recent Venice Biennale. In addition, GMF’s invitation to Dan Cameron, Natalia Zuluaga, and myself to interface with Kentucky artists exposes those artists to our respective networks, resources and conversations.

By attracting well-heeled and well-traveled individuals to the various 21C Museum Hotels and restaurants, this hospitality group plays a significant role in increasing exposure to and awareness of the Kentucky artists’ works represented in its collections. I viewed my postponed curatorial project, Icon Interventions, at 21C Lexington, as a similar potential force. In addition to changing exhibitions at the museum, the KMAC Triennial, organized through a committee led by curator Joey Yates, is a welcome format encouraging further dialogues between Kentucky artists while fostering attention from beyond the state’s borders.

Requiring funding and an enterprising spirit, national and international art events, including biennials, art fairs, and out-of-state group exhibitions offer more opportunities for Kentucky artists to gain further visibility. To gain further insight into the growth of the Kentucky Art ecosystem, fundamental issues require scrutiny:

- Do Kentucky artists want these conversations or are many satisfied with the status quo?

- What are the motivations, goals, and desired results to have these conversations?

- A rising Kentucky artist moves away to pursue further education.

- Will this artist return? Why or why not?

- A talented artist moves to Kentucky for a faculty position and lower living expenses.

- How does one encourage this artist to stay?

- How does one attract other talented artists to come and settle here?

- A certain Kentucky artist has the skills and reputation that could serve this artist well in larger cities like Los Angeles and New York.

- What keeps this artist in Kentucky?

- How does Kentucky keep this artist from moving away for other opportunities in larger cities?

To be fair, my comments are made with the presumption that artists hunger to extend their reach further. Some may not. There may be a case for maintaining the status quo. In the exhibition catalog for Here, contributor Mark Harris remarks, “Paradoxically, the circumstances that prevent this art from circulating at a national level are the same that enable it to gain its distinctive local color and depth.†Throughout my rewarding four month long experience as Critic-in-Residence for the Great Meadows Foundation, it has been a distinct honor and an absolute pleasure to work with all of you and especially with several extraordinarily gifted artists. I am invested in the creative communities of Kentucky, and offer my continued support and friendship from Los Angeles, Honolulu, and New York.

Mahalo nui loa!

Photo credits: KÅan Jeff Baysa