The solo exhibition Under the Eyes of a Dry Mountain by Aaron Michael Skolnick at MARCH gallery in New York City (October 13-November 27, 2022) features his most recent oil on canvas paintings presented in two distinct bodies of work.

Under the Eyes of a Dry Mountain refers to ten paintings that were conceived and executed en plein air. The artist decided to leave the four walls of his studio in order to experience creating landscapes in the environment surrounding his home and studio in Old Chatham, New York. When observing them together they become a rumination on the fleeing of time. Each piece validates how different parts of the day can invoke contrasting feelings within us. Skolnick establishes very precise tonal values amongst this group of ten paintings, choosing the most appropriate color ranges for representing different parts of day or night. These 4′ x 3′ canvases are laced with observation; the artist took the time to be intimate with the nature around him and perceive it fully in solitude. He discerns every little patch of land, mud, leaf, the earth, and the hues of the bark on trees. Shadows and sunlight melt into one another, drawing attention to the movements of light from morning to dusk.

When recollecting memories of his childhood, it was occupying space alone in nature that felt the safest. To Skolnick, they always felt magical and continue to be a leitmotif in his oeuvre. Representing the infinite in different parts of the American landscape – whether it be the west, east or south – is something that has been preoccupying his painting practice for some time. The woods become a place of self-reflection and a space to simply be and allow yourself to notice what appears. In a sense, this process can be compared to the practice of meditation where the aim is to skillfully allow the subconscious to arise into consciousness through patience and time.

The evolution of American landscape painting spans more than three centuries and its representation has often prompted awe, wonder, and reverence. Early American painters used landscapes only as backgrounds for portraits but, in the early 19th century, landscape painting became the vehicle for representing American identity. The Hudson River School was an informal group of like-minded painters founded by Thomas Cole (1801-1848). Their new style of representation was in sync with realism, advocating a respectful and pacifist relationship between the order of society and the splendor of nature. The theme of wilderness had earlier gained currency in American literature, especially in the “Leatherstocking†novels of James Fenimore Cooper, which were set in the upstate New York locales that became Thomas Cole’s earliest subjects, including several pictures illustrating scenes from the novels.

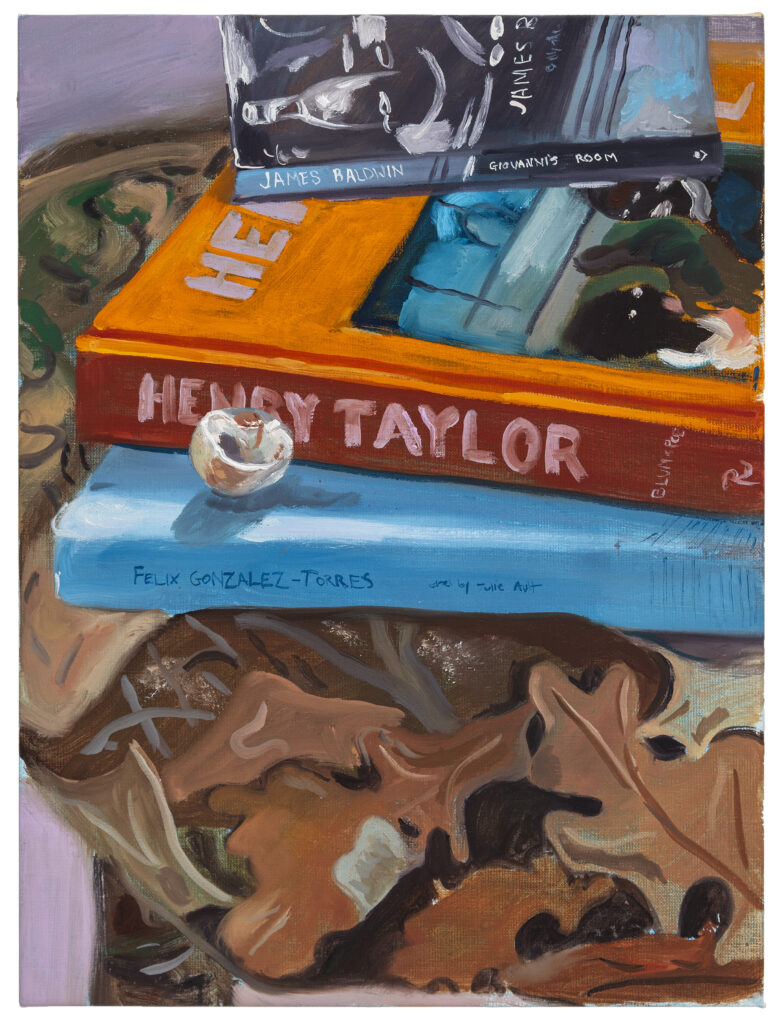

The second group of paintings exhibited in the north part of MARCH gallery represents a non-linear narrative often set in human-scale domestic spaces as well as nature. Devoid of the human figure the paintings offer us only a certain number of clues, leaving it to us to decipher their deeper meaning. Folds of camouflage fabric echo the artist’s surroundings and perhaps allude to hidden identities. Camouflage, also called cryptic coloration, is a defense that organisms use to disguise their appearance, usually to blend in with their surroundings or to mask their location, identity, and movement. Maybe Skolnick decided to mask the memories he had while creating these paintings and not be explicit about them. About his art, he says: “Although my work is extremely personal, it is not autobiographically about everyday life; it is about intimacy.†A number of the paintings outline several books mentioning their titles and authors including the monograph of the late American artist Feliz Gonzalez-Torres. Perhaps Skolnick chose to portray this publication because the practice of this artist was deeply invested in depicting personal and intimate life moments. Gonzalez-Torres’s groundbreaking installations are famous for their simplicity and affective impact, embedding poetic meditations on love and loss. The diverse and ambiguous meanings of his work allow each spectator to have a unique experience and response.

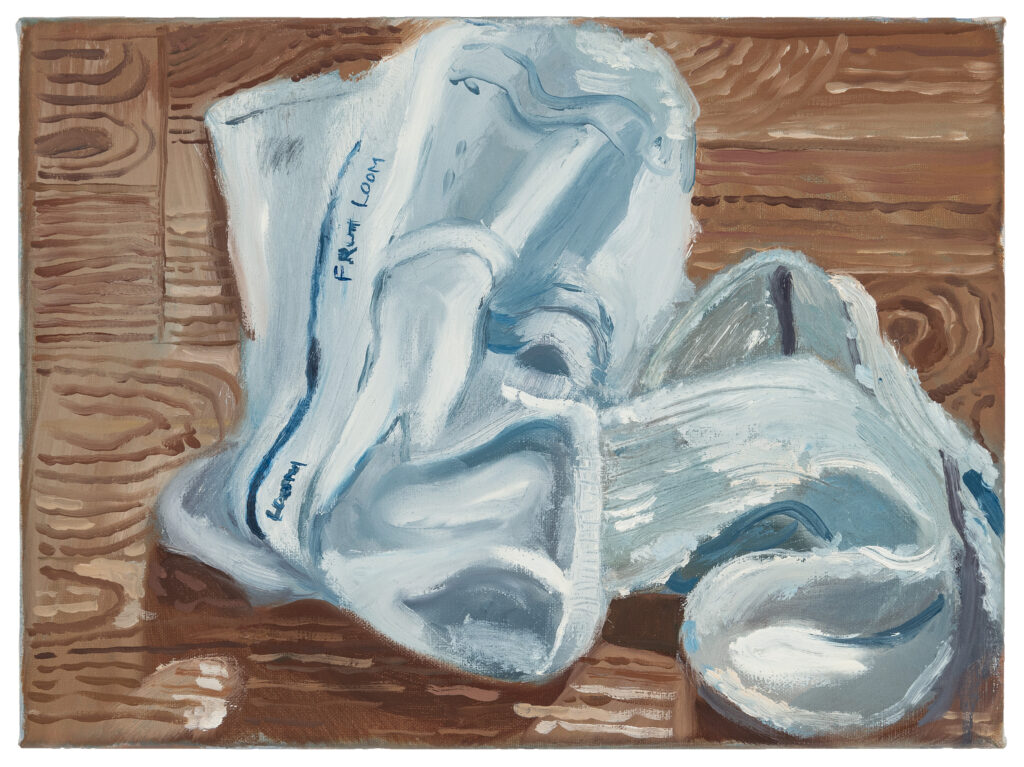

A small 9†x 12†canvas titled After working on the trail portrays men’s underwear and socks left on the floor. It is possible that this piece is a nod to the artist’s previous body of work where bodily form and desire were very much at the forefront. Hinting at erotic anticipation without revealing much can sometimes be much more thrilling. It is possible that the artist is eliciting our curiosity by showcasing intimate garments in a painting or they just happened to be sitting on the floor after a day of working on the trail and they seemed to be good material to portray.

Skolnick acknowledges that paintings need a lot of patience to produce, and he perceives each new piece as a little battle. During the time he spends in front of them he works and reworks each piece through different processes until he intuitively feels they are finished. Most of the canvases in this exhibition pay homage to nature in the broadest sense, referring to the phenomena of the physical world and also to life in general. The 19th-century philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote about nature: “There I feel that nothing can befall me in life – no disgrace, no calamity (leaving me my eyes), which nature cannot repair.â€

Top image: Installation image of exhibition Under the Eyes of a Dry Mountain by Aaron Michael Skolnick at MARCH gallery, New York City. Photographed by Cary Whittier, provided by MARCH gallery. Six paintings of nature scenes hang on white gallery walls.