As a photographer reviewing photography exhibits, I feel I might bring some baggage to my reviews. I also worked here at the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MOCP) at Columbia College Chicago, as a student. Hopefully, neither of these facts will cloud or impact this review, but just in case I am adding this disclaimer.

I find group exhibitions a bit difficult to review. I want to give equal time to all those included and be careful not to just skim the surface, especially with an exhibition as important as American Epidemic: Guns in the United States.

This is no small exhibition, and it is given the entire museum space encompassing all three floors. The first and main gallery goes to the work of Andres Gonzales and his project American Origami. The work isn’t just photographs; it contains heartbreaking mementos many left at the sites of the school shootings he has been photographing.

Gonzalez began this project shortly after the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut. Unfortunately, his project, like school shootings, didn’t stop there. He visited the seven sites of the deadliest school shootings in recent decades.

Images of buildings and landscapes where the devastating shootings occurred are in sharp contrast to his tender portraits filled with pain. Gut-wrenching statements of survival and loss accompany them.

“But when you have a child, or a young adult like Mary was, who is deliberately taken, it’s not loss — she’s taken from you by another person in a violent act.“

Andres interview of Peter Read, Annandale Maryland. Talking about his daughter Mary who was killed at Virginia Tech.

An image of a hallway feels cold and empty, lacking life, yet you can almost feel something lurking in the open space. I find myself wanting to peer around the corner in the image and look for those who I know are hiding under desks somewhere. I shudder at the thought of a shooter stalking them.

In the middle stands a podium with folded brochures filled with the President’s Speeches from May 20, 1999, April 17, 2007, December 16, 2012, and February 15, 2018, each given after a school shooting. What stands out in the brochure is the blank pages where speeches should have been. Presidents Bush and Trump did not give one. The viewer may take a copy of one of the pamphlets when they leave.

Zora J. Murff’s work I am very familiar with. His work seems to be everywhere these days, in particular the large beautiful color portrait of Terri (talking about the freeway), 2019, which is from his larger series shown here. His statement speaks of the beginnings of this project, No Point in Between, which began after the killing of Laquan McDonald by police officer Jason Van Dyke in Chicago in 2014.

The image of Terri, like the image of Jerrod and Junior (talking about fatherhood), 2019, offers gentle warm photographs. However, this project as a whole is far from gentle and warm. It is about the cold reality of redlining, racism, and repression. From lynching and Jim Crow laws to the murder of Laquan McDonald.

Like the work of Gonzalez, Murffs’ work includes other items, including historical photos and a newspaper clipping about the police officers who were charged with Laquan’s murder.

While all the images were made in the area of North Omaha, Nebraska, they represent every city and town. Encompassing repression, systematic racism, and the murder of innocent black folks.

Carolyn Drake’s piece One thousand and four Americans were killed by police officers in 2019 (2020) is of a black quilt that lures me to reach out and touch it, that is, until I learn about it. It is made up of old police uniforms, which she purchased from eBay. Each of the 1,004 squares representing the 1004 victims killed by police in 2019. The wanting to reach out and touch it turns into wanting to wash off my hands as to not have them stained.

Almost forgotten in the backroom is another takeaway piece by the artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres “Untitled†(Death by Gun), 1990. The work was inspired by a 1989 Time magazine article that listed the names and causes of death by gun in a one-week period in 1989. The clean lines of the stacked piece hold the jagged-edged stories from suicide to homicide.

You walk up the stairs to a young girl holding a pistol, the work by Nancy Floyd. She began her project She’s Got a Gun (1993-2008) of women gun owners in the early ’90s after purchasing her own gun in 1991 to better understand her late brother’s gun enthusiasm. These are large Chromogenic prints with stories of each woman and their connection to guns.

You don’t necessarily need the text as the images are standalone eye-catching photographs, but once you read one story, you want to read more about each woman and their attraction to guns and gun ownership. I am not a gun owner, nor am I a fan of them, but the explanations helped open my eyes a bit and my understanding of some views I do not share.

In a statement by Maggie C. Brown: “My mother had eleven children. I’m the baby. The youngest sister left home when I was eight years old and I grew up with my brothers. They would take me to hunting and they got me a twenty-two Rifle. We’d hunt sometimes two or three times a week and I finally learned to shoot as good as they did, even better.â€

While viewing Floyd’s work on the second floor, I heard what I first thought were screams of a gunshot victim. It was indeed a victim, the grandmother of Robert “Yummy†Sandifer who was murdered at the age of eleven, a victim of gang violence in Chicago. It was her wails I heard at his funeral in the video Libation (2018) made by the artist Stephen Foster.

The video is in a dark space at the top of the stairs on the way up to the third floor where you can view it and grieve alone.

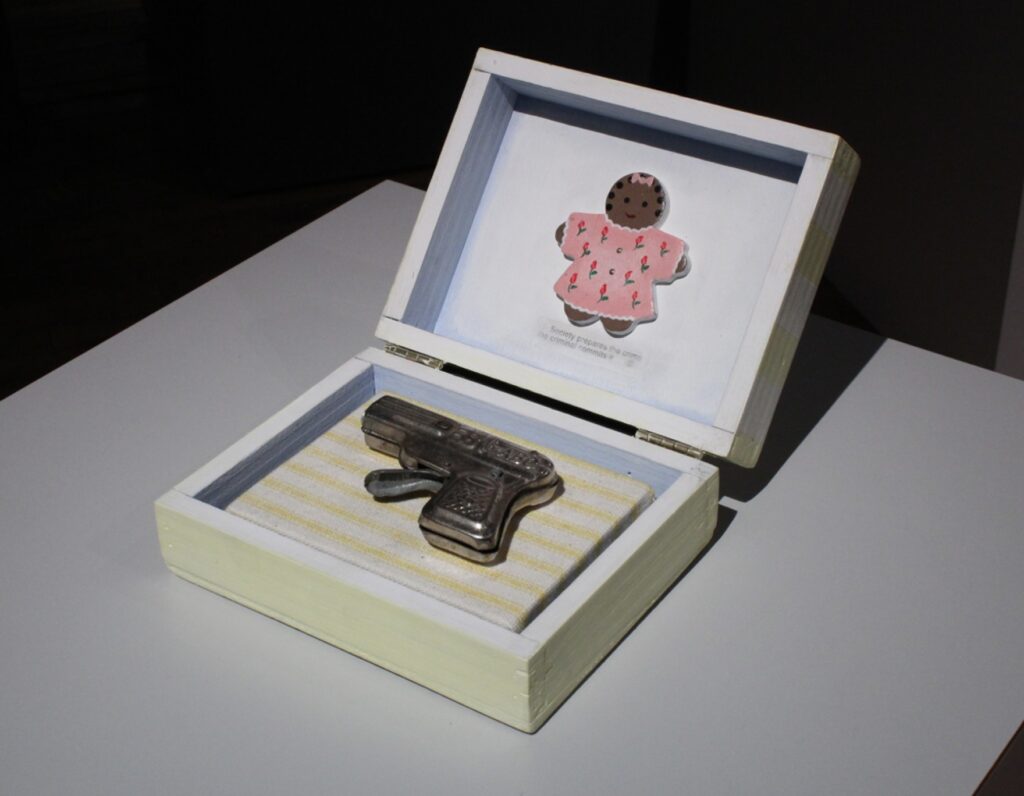

In Renée Stout’s “Baby’s First Gun†(1998), a small cap gun and gingerbread cutout in a small wooden box remind us of the young age children are first exposed to guns.

It is displayed in between two artists whose works I greatly admire, Hank Willis Thomas and Deb Luster.

Hank Willis Thomas has the ability to be a creative master in whatever medium he takes on. For this exhibition, it is in a video collaboration with Kambui Olujimi and plastic GI joes. The video Winter in America, (2006) tells the story of his cousin Singa Thomas Willis who was killed outside of a club in Philadelphia in 2000.

The plastic toys come to life, telling the story of his murder. It doesn’t matter that the plastic toys and blood are not real. The color drips out of the plastic GI Joe, and he becomes tragically real in this almost five-minute video.

Deb Luster has a lot of personal history tied up and around guns. Her mother was murdered with a firearm, leading her to photograph prisoners for six years.

Her project Tooth of an Eye (2011) contains images of New Orleans photographed with an 8×10 camera and a lens that creates a circle to mimic a gunshot. The quiet gelatin silver photographs are of historical and recent homicide sites in New Orleans, which has one of the highest homicide rates in the country.

Somehow at the end of the exhibit, I am left with no images or words at all. It is the take-home sheet with the Presidents’ speeches on the school shootings or lack of them. It was Bush and Trump who said nothing, and that for me says it all.

American Epidemic: Guns in the United States is on exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Columbia College Chicago, through February 20, 2022. All images provided by the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago. Top image: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled†(Death by Gun), 1990. Courtesy of the Collection of The Museum of Modern Art New York, purchased in part with funds from Arthur Fleischer, Jr. and Linda Barth Goldstein.

UnderMain: On the Road sends writers out of Kentucky to explore the visual arts in cities of the Midwest and near South. This program is generously supported by the Great Meadows Foundation.