When I first walked in to view the National AIDS Memorial Quilt exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art (moCa) Cleveland, it didn’t feel like much of an exhibit as it was so small. It only consisted of two panels from the quilt.

The Quilt memorializes 125,000-plus victims of AIDS and HIV-related illness; it is made up of individually created three by six-foot panels—each the approximate size of a grave. Currently spanning 1.2 million square feet and weighing 54 tons, the Quilt is a powerful symbol of the AIDS pandemic and a living memorial to a generation lost to AIDS and HIV-related illness.

I am old enough to have seen the quilt when it first began to tour. I remember the half a million people who visited it on opening weekend on the national mall. I stood in line for hours to view it when it first began to tour, looking with strangers for the names of friends and loved ones who had died as a result of AIDS.

I forget that younger people don’t know about the quilt and its history. I was reminded of this when I met Duncan Smith, who was working at the museum with this exhibition. “I was not alive during the AIDS crisis, I wanted to work here as I connected to the art as a gay man; it was a way to connect to my predecessors.†A statement that got me thinking about the quilt in a new way, as education.

With a closer look at the quilt, this exhibition though a small one, came into full view. I saw the name “Mundo†Meza on one of the two panels of the quilt, and I understood the connection between this and the Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. exhibition. In many ways, the exhibition felt backwards with the epitaph first.

“Mundo,†short for Edmundo Meza, was a prominent figure during the days of gay liberation and Chicano civil rights, a much-loved artist and activist whose work has been rarely seen until now. Organized by ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries, Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. maps the intersections and collaborations among a network of queer Chicano artists and their artistic collaborators from the late 1960s to the early 1990s. A time that included gay liberation, feminist movements, and the AIDS crisis. Collected and curated by C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz.

When you first walk in you can’t help but notice Robert Lambert’s rhinestone denim jacketed mannequin in the center wearing quilted pants and platform shoes, a holdover from the days of disco. The mannequin feels as though it is overseeing the exhibition, which includes images of drag queens, parties, and poems. The first room is full of life, with few hints of the AIDS crisis yet to come.

Housed in clear plastic is a series of postcards created and mailed between 1975 and 1978. A different world before the days of YouTube and Instagram, a time when getting your work seen and your voice heard was not always an easy task, but it did bring about a world of creativity.

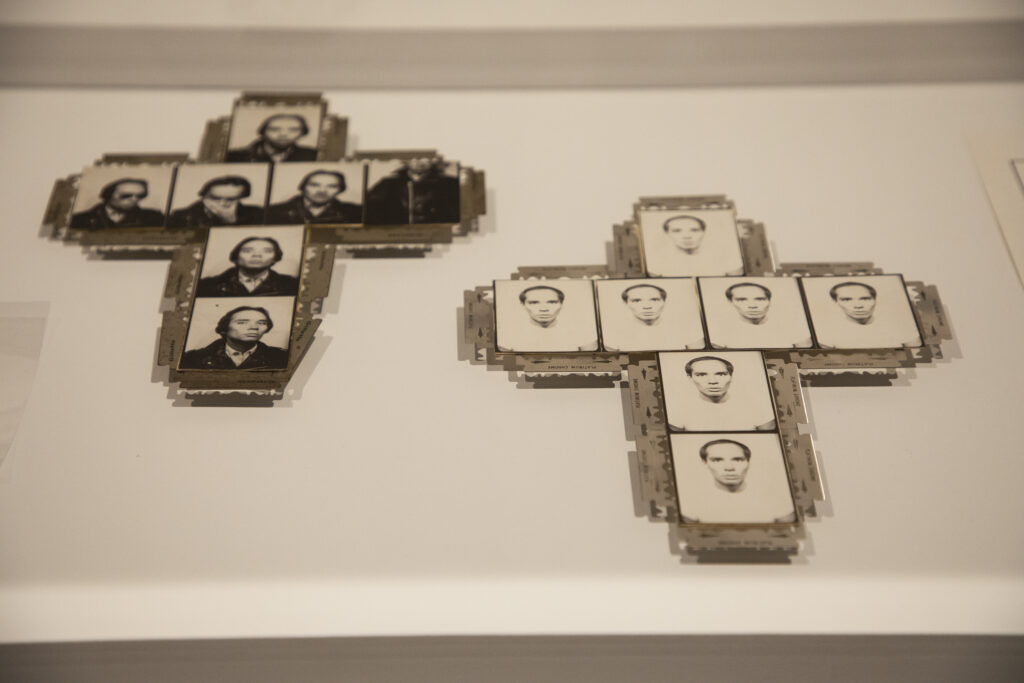

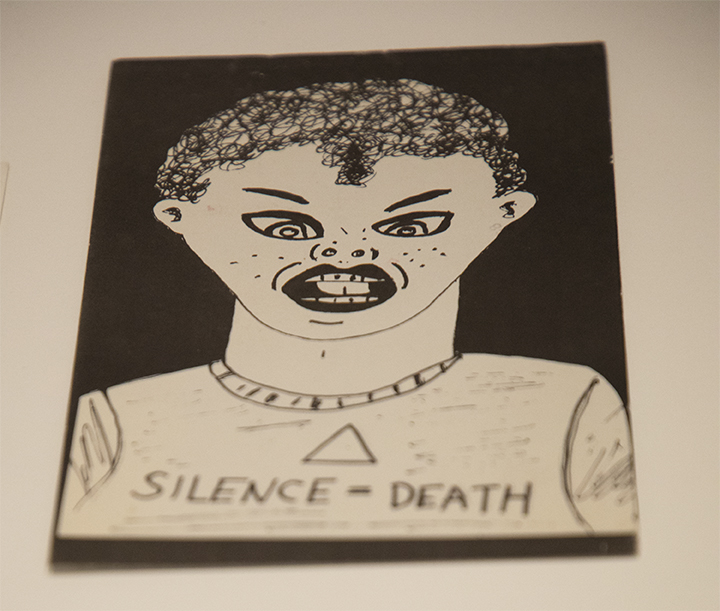

Jerry Dreva’s Razor Blade Cross (c.1980) sent to Grank; just imagine trying to mail razorblades today. Tomata du Plenty’s Silence=Death postcard sent to Jim Yousling is an excellent example of art with a mission.

A self-described Latina Lesbian, Laura Aguilar has numerous photos here, including two from her Painted Pony series named for the lesbian bar where she set up a makeshift studio and photographed the regulars.

Two of these hang next to the painting by Jef Huereque, of his My parents in their Matching Zoot Suits, c1973, the artwork giving hints to his later career as a fashion designer.

Additional images by Aguilar include a series titled Latina Lesbians, photographs of friends, and friends of friends. Aguilar asked her subjects where they would be most comfortable being photographed, which is where she made the image. She also requested they share a personal story and handwrite it under the photo. Giving them a voice and allowing the viewer to hear them.

Mundo’s monochromatic mermaid, his ripped macho stomach on top matches the scales on the bottom of the mermaid. The painting reflects “beefcake†magazines marketed to gay men from the 1930s through the 1960s. The painting is based on a photograph of Tony Sansone by Arthur Lee from the 1930s.

The 1983 self-portrait Mundo Meza, is far from the macho mermaid created a year later. It is almost like two different artists created them. One can’t help but wonder whether he had received the diagnosis of AIDS in between creating the two paintings, as they feel worlds away from each other or perhaps that was just one of Meza’s many talents as an artist; you wouldn’t know what was coming next.

The second room has numerous videos created by Ray Navarro videos trying to get across the urgency of AIDS; he was a founding member of DIVA TV (Damned Interfering Video Activist Television)—the video affinity group of ACT UP/New York—Navarro worked to educate AIDS activists outside of the mainstream.

His three stark black and white photographs Equipped, 1990 Hot Butt is of a wheelchair, Stud Walk is of a walker, and Third Leg is of a cane. His friend and artist Zoe Leonard helped him create these. Navarro had lost his hearing and sight due to AIDS, but not his sense of humor.Â

A young woman sits alone watching the Navarro video from 1989 titled Stop the Church about the Catholic church’s negative views on AIDS and gays. She wasn’t alive then; she wouldn’t know or remember this time of crisis and art activism or that so many artists were taken from us too soon in the middle of it.

Photography by Sarah Hoskins.