This year, when documenta 14 expanded its scope to include the city of Athens, Greece, an LGBTQI refugee rights group seized a sculpture from the exhibition and refused to give it back. The sculpture was Roger Bernat’s Replica of Oath Stone—a porexpan and fiberglass copy of a limestone table present at the trial of Socrates in 399 BCE. According to the project handbook, Bernat’s sculpture was to be walked through Athens in a mock funeral procession and then sent to Kassel to be entombed in the Thingplatz—a Nazi-era theatre. Bernat paid the group to participate in the performance—but this transfer of money ignited a larger conversation about debt, labor, and the effects of large-scale exhibitions. The group confiscated the stone and in its place left a ransom note that stated:

You have come to Greece to make art visible and graciously offered to purchase the participation of invisible exoticized others. Â

As Kentucky continues to rethink and transform its visual arts communities, might we also begin to treat similar paradigms that exist in contemporary art? Erica Rucker’s recent LEO Weekly article discusses an optimistic present: a moment in time when Kentucky’s museums and galleries are reevaluating their exhibitions and programming. But while documenta 14 and the 2017 Skulptur Projekte address inclusivity, they also challenge the framework from which exhibitions are often produced.  Â

Indeed, biennales and large-scale exhibitions have made attempts to define contemporary art using a Western-centric model. Miwon Kwon, curator and art historian, argues that groups considered peripheral to “dominant culture thus [become] objectified once again to satisfy the contemporary lust for authentic histories and identities.â€1 Cultures are often treated ethnographically—as objects of study to be organized by curators and contextualized by a Western framework.2

For their 2017 iterations, documenta 14 and Skulptur Projekte Münster are critical of their established transnational appeal and central European locale—but do not reject either. Rather, these issues become the central focus for their curatorial teams. Â

documenta 14Â Â

Previous documenta curators (Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Okwui Enwezor) have invited international artists to create work that considers the effects of Western institutions and globalization. As stated by documenta 14’s Artistic Director Adam Szymczyk, however: it is almost impossible “to realize a project that aims at making a political statement from within a state-subsidized cultural institution (one with additional institutional, corporate, and private funding involved, of course).â€3

This year, documenta 14’s curators address issues of inclusivity and cultural objectification by dividing the exhibition between Kassel, Germany (its standard location) and Athens. Greece’s identity as both a genesis of European civilization and its contentious relationship with the European Union (most notably, Germany’s role in its financial depression) have, according to Szymczyk, resulted in “the loss of Greek citizens’ individual freedom.â€4 Â

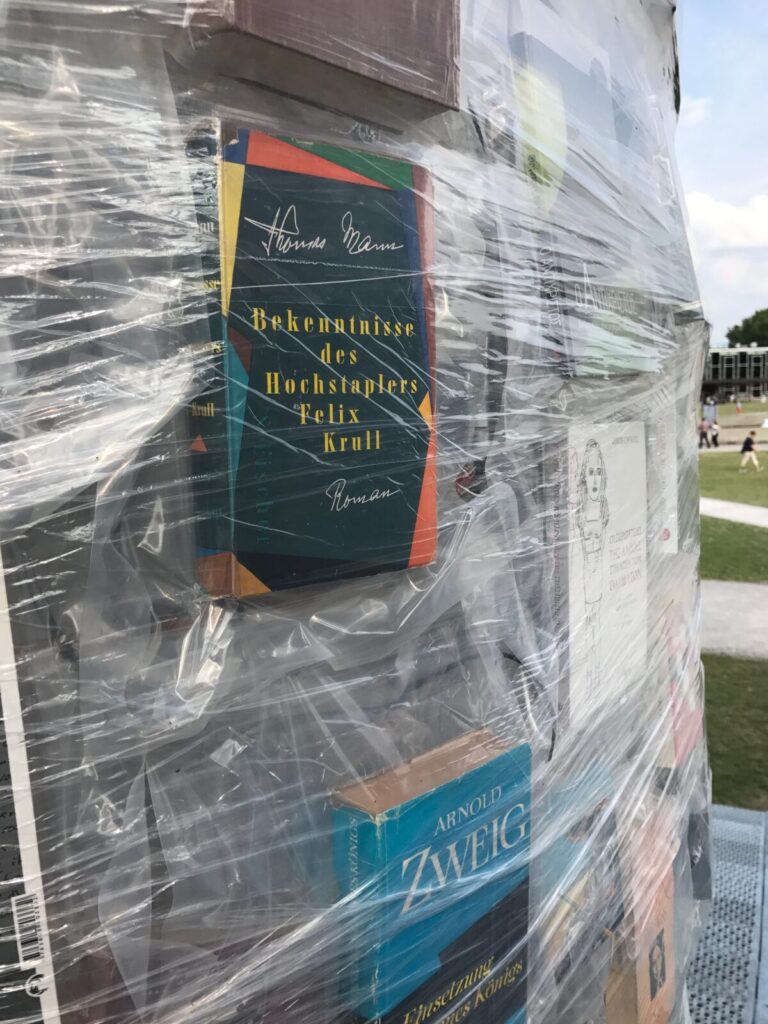

Many of the artists included in documenta 14 mine the cultural significance of existing Western monuments that have come to represent concepts of freedom and democracy. The city’s central square is a warning that history is cyclical: Marta MinujÃn’s The Parthenon of Books, a replica of the temple on the Acropolis in Athens, is composed of 100,000 banned books from across the world—but this is not her first construction of renegade literature. In 1983, to mark the end of Argentina’s civilian-military dictatorship, she built El Partenón de libros from the confiscated books that had previously been under lock and key. Adjacent to MinujÃn’s Parthenon stands Kassel’s Fridericianum—traditionally the centerpiece of each documenta exhibition.

In place of the institution’s name, artist Banu CennetoÄŸlu has shuffled the large aluminum letters (and added six additional ones) to read BEINGSAFEISSCARY. Although CennetoÄŸlu states that the phrase is based on graffiti found at the National Technical University of Athens, it also pays tribute to freedom fighter and Kurdish journalist Gurbetelli Ersöz. Her diaries were posthumously published in Germany, and later a small Turkish press also attempted to do the same—but they were subsequently banned in 2014 by Turkey’s ruling administration. Most works that surround Kassel’s Friedrichsplatz reference the censorship enacted by fascist regimes, as the Third Reich used the park to display political power through large military parades. White smoke billows from the Fridericianum’s tower where artist Daniel Knorr’s Expiration Movement is a reminder of the Nazi’s burning of books in 1933. Â

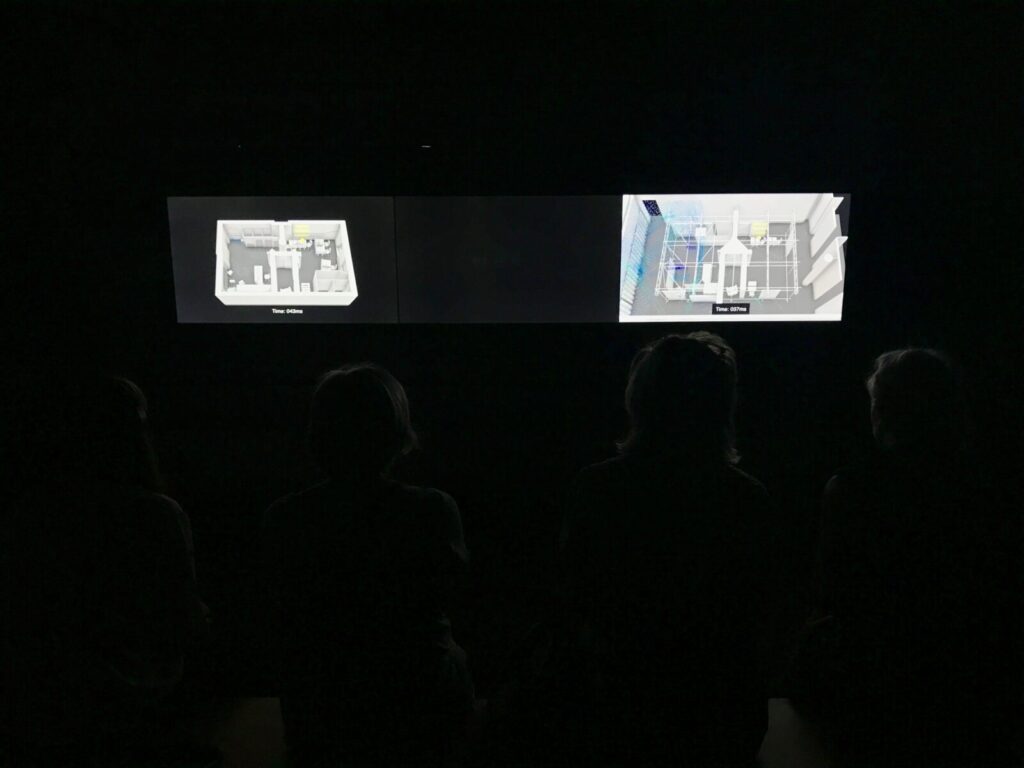

Other sites within documenta 14 are new to the 2017 exhibition. The Neue Neue Galerie is located in Kassel’s Nordstadt—a neighborhood home to the majority of the city’s immigrant populations. Formerly the Neue Hauptpost (but renamed by documenta 14’s curators), the brutalist building was once home to city’s main post office. Its industrial use shed by increasing digital communication, the building contains loading docks that are repurposed as mini-galleries. The building’s dim lighting allows for the multiple new-media works to be viewed without interruption from sunlight, but also makes for a foreboding atmosphere. In the corner is 77sqm_9:26min: a digital investigation of the murder of Halit Yozgat—the ninth of ten victims in a racist murder series committed by the neo-Nazi organization the National Socialist Underground. Â

Â

Skulptur Projekte MünsterÂ

The effects of biennials and large-scale exhibitions extend beyond the contemporary art realm. The merits of such massive art events, at least for their respective local economies, are plentiful: cities have the opportunity to merge their existing arts communities with a global contemporary art discourse and foster a more robust cultural exchange. Artists included in Skulptur Projekte reference the local and regional histories, industries, and cultures of the sites they inhabit, but also consider how the a city’s reliance on cultural tourism can be an indicative feature of public art. Unlike documenta, Skulptur Projekte is free to the public.Â

Skulptur Projekte internalizes and embraces the merits, pitfalls, and ironies of cultural tourism. Michael Smith’s Not Quite Under_Ground—“the official tattoo studio of Skulptur Projekte Münster 2017â€â€”offers an expansive array of artist-designed tattoos ranging from past Skulptur Projekte participants to Smith’s personal friends. The shop’s name references the increased cultural acceptance of permanent body art since the 1990s, but also Smith’s observation that senior citizens are frequenting Münster as tourists (the artist produced an accompanying video that may be viewed both in the tattoo studio and on YouTube.) As a result, Not Quite Under_Ground offers deep discounts to those sixty-five and older who wish to participate. Each tattoo provides a permanent souvenir while extending the lifespan of the exhibition through what Smith describes as “the storage medium of the skin.â€Â

Outmoded idioms of “public†and “private†become catalysts for many artists asked to participate in Skulptur Projekte. On the other end of Münster, in the city’s inland harbor, Ayşe Erkmen has installed a covert jetty between the waterway’s northern and southern piers. Existing just below the water’s surface, the industrial sheen of ocean cargo containers and steel grates is camouflaged by the water’s silver reflections. Visitors remove their shoes and step into water—creating the impression that they are walking on Münster’s river.

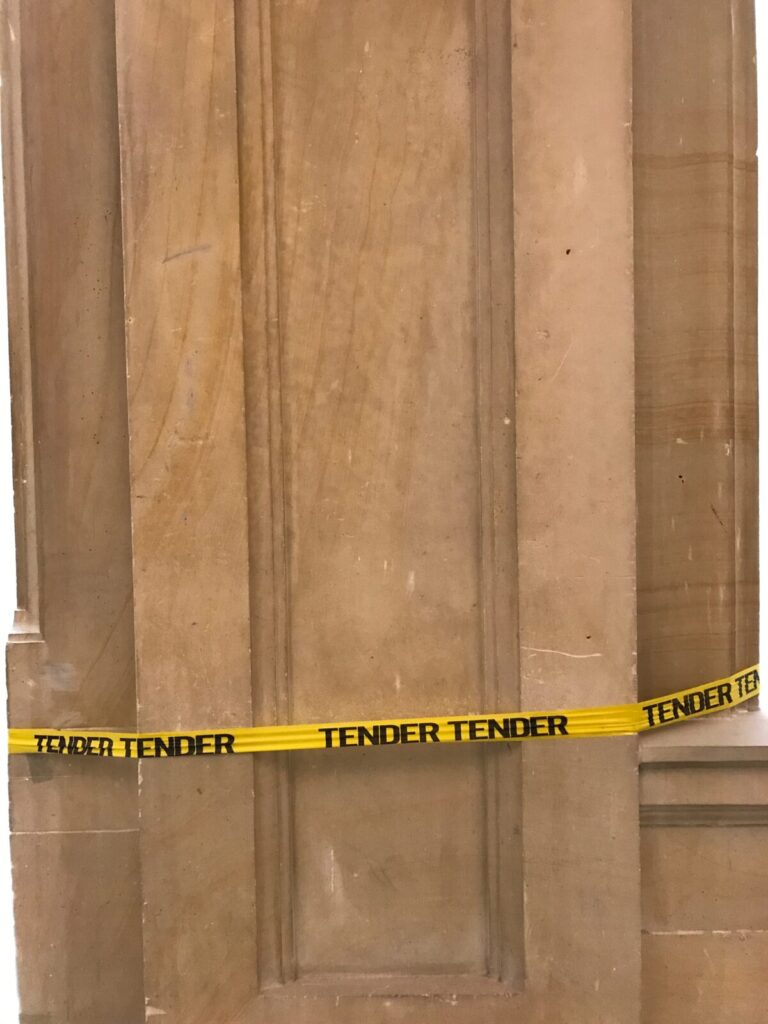

By linking two urban spaces, Erkmen questions the sociocultural and sociological effects of city planning. When represented on maps, waterways—whether manmade or natural—indicate geographical boundaries that can restrict pedestrian movement. Opening the city’s harbor to foot traffic, On Water is a consideration of the relationship between city planning and accessibility. Münster’s LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur is also altered—Michael Dean’s Tender Tender establishes a space within a space by installing a large opaque plastic sheet inside the museum’s atrium. Reaching from ceiling to floor, the plastic creates a canopy that alters visitors’ normal movements. Inside the canopy, Dean has sculpted the detritus of city life; trash cans, stickers, painting tape, stones, wires, and grocery bags loosely resemble street lamps and sidewalks. Â

documenta 14 and Skulptur Projekte Münster—although they differ in size and scope—attempt to question and reform constructs that have been shaped by Western culture. This attempt, however, can fall short when it is not fully realized. The LGBTQI refugee rights group made a specific statement when they captured Replica of Oath Stone: the dangers of artists and exhibitions addressing inclusivity without unfixing dominant ideological structures in contemporary art that oppress—and in turn “ exoticizeâ€â€”“others.†Kentucky’s visual arts community is slowly progressing toward a more inclusive future, but exhibition spaces, museums, and cultural institutions are still defined by regional and local ideologies. Germany’s major tourist events of 2017 are marked with failure, but these failures are catalysts for imperative discussions about otherness, globalism, and complicity.

1. Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2002), 138.

2. Paul Wood, The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s) (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2012), 53-54.

3. Adam Szymczyk, et. al., The Documenta Reader (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2017), 22.

4. Szymczyk, The Documenta Reader, 23.

Â