Drawing comparisons between images of two disparate periods in the twentieth-century history of photography—and the artists who worked in these respective moments—is a precarious curatorial endeavor. Face Value: Photographs by Doris Ulmann and Andy Warhol is akin to a tight rope walk, as the exhibition attempts to connect the portraits taken by Ulmann (1882-1934) and Warhol (1928-87) without addressing major shifts in photographic practice.

Beginning in the early twentieth century, a new wave of artists became increasingly critical of the camera’s efficacy of truth telling. These artists subscribed to the idea that reality—as depicted through the lens of a camera—had collapsed on itself. The photograph became increasingly self-reflexive; artists sought to prioritize the medium’s visual disconnects rather than construct a banal narrative around the image of a static landscape or individual.

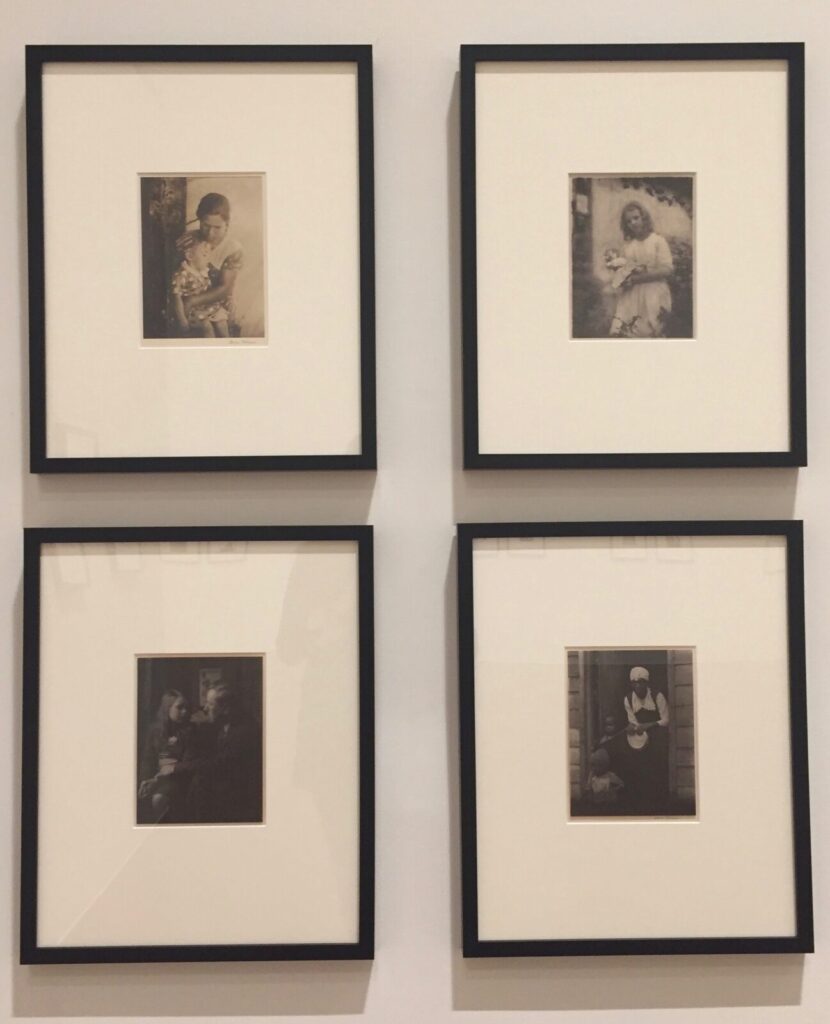

In Face Value, the historical and analytical gap between Warhol’s snapshot-style photographs and Ulmann’s highly stylized portraits is a source of both contention and intrigue. The exhibition’s exclusion of medium-specific history results in a distinct emphasis: the individuals Warhol and Ulmann chose to photograph. Although strikingly different in composition and method, Ulmann and Warhol’s photographs document musicians, friends, lovers, dancers, celebrities, and writers.

While the majority of Ulmann and Warhol’s portraits in Face Value are thematically grouped, specific photographs have been intentionally coupled and presented as side-by-side comparisons, illuminating the artists’ adherence to—or disavowal of—medium-specific traditions. Warhol’s black-and-white photograph of the legendary ballet dancer Jock Soto—presumably taken in the late 70s or early 80s—is paired with Ulmann’s 1919 portrait of choreographer Michio ItÅ. Warhol’s image of Soto pushes against its “portrait†categorization, as the subject’s hand is rendered the central focal point.

Indeed, Warhol’s “portraits†often reveal the artist’s concentration on fragmented bodies—hands, torsos, and arms supersede his subjects’ faces. Two horizontal lines interrupt the image’s top-right corner, accentuating Warhol’s interest in the vernacular traditions inherent in amateur photography. On the contrary, Ulmann’s Michio ItŠis posed, specifically, for the camera’s lens. The choreographer’s body is shroud in thick dark fabric, leaving only his face exposed.

Ulmann and Warhol’s photographs are aesthetically and analytically incongruous—yet their juxtaposition in Face Value exemplifies Modern photography’s historical break from Pictoralism and “straight photography.†Challenging what the American photographer Edward Weston had described as the “quality of authenticity in the photograph,†Warhol’s images break from former practices that relied on expensive equipment, precise lighting, and staged compositions.[1] Instead, the artist used inexpensive cameras, including The Polaroid Big Shot and Olympus Quick Flash.[2]

Comparing Warhol’s snapshot aesthetic and Ulmann’s painterly photographs exhumes complex issues rooted in the medium’s evolving methods, but also presents a more nuanced reading of the instability of class consciousness, constructions of identity, and artistic subjectivity in twentieth-century photographs. Ulmann’s Melungeon Woman at a Washtub (n.d.) is constructed to portray Appalachian life through a specific lens—that of a wealthy, educated, New York woman. Posed with washboard and basin, Ulmann’s subject does not confront the camera. Rather, her gaze is directed outward in meditative contemplation. Ulmann, in her chauffer-driven Lincoln, traversed the rural United States seeking subjects that could best condense rural life into a singular image. As a student of the Ethical Culture Movement, her interest in rural subjects stemmed from a humanist tradition: she sought to capture “vanishing types†whose way of life was under threat in an increasingly industrial America.

Ulmann adhered to Pictorialist traditions that included the use of various blurring techniques to mimic features of painting, in addition to an intent concentration on compositional simplicity. Lighting effects, often produced through a greased lens and soft focus, provided a luminescent atmosphere.[3] For Pictorialists, idea, message, and emotion were paramount to a photograph’s construction. An emphasis on “traditional beautyâ€â€”an indeterminate concept that, for the Pictorialists, was seemingly universal but vaguely defined—was often used to dramatize portraits or landscapes.[4]

To connect the approaches and photographs of Warhol and Ulmann seems, at best, a forced marriage—a coupling based on superficial traits. The value of Face Value, however, lies within the irony of its title in relation to the subject of portrait photography: portraiture can never be taken at “face valueâ€â€”the photographer’s framing of people and events presents a constructed version of reality. Face Value recognizes this tension—at least partly—through the exhibition’s wall text. Warhol and Ulmann’s respective socioeconomic backgrounds (Warhol from blue-collar Pittsburg, Ulmann from an affluent New York family) profoundly influenced their choice of subjects. Both oscillated between paparazzi and voyeur—Warhol and Ulmann’s subjects often served as a mirror from which the photographers could examine their own lives.

Face Value: Photographs by Doris Ulmann and Andy Warhol runs through April 23, 2017 at the University of Kentucky Art Museum.

[1] Edward Weston, On Photography, ed. Peter Bunnell (Salt Lake City, Gibbs M. Smith, Inc., 1983), 51.

[2] Stephen Petersen, Andy Warhol: Behind the Camera, exh. cat. (Newark: The University of Delaware, 2011), v, xi.

[3] Christian A. Peterson, After the Photo-Secession: American Pictoral Photography 1910-1955, exh. cat. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company and the Minneapolis Institute of the Arts, 1997), 18.

[4] Peterson, After the Photo-Secession, 18.