With the death of Dr. Leonard Leight at age 98 on March 9, 2021, the majority of the collection assembled by Leonard and his late wife Adele has passed to the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky. Their gifts are the subject of a current exhibition at the Speed Art Museum that takes up four galleries. The exhibition, Collecting – A Love Story: Glass from the Leonard and Adele Leight Collection has been extended through November 7th. The Leights’ bequest includes over 450 works of art, 240 of which are works of contemporary glass. This gift is a major event in the history of the Speed Art Museum.

Speed Art Museum Curator of Decorative Arts Scott Erbes chose Norwood Viviano as co-curator to aid in the selection of the 69 works in Collecting – A Love Story: Glass from the Leonard and Adele Leight Collection. Viviano, an innovator in 3D printing, scanning, and laser cutting in glass, recently has developed a technique for making his cast glass works multi-colored. The exhibition illustrates the drive of individual artists to make something never seen before wrought in glass. The Leights were in thrall to the virtuous circle in glass art of the past 50 years, technological improvement driving artistic form, artistic form in turn propelling new experimental methods. A wide variety of fabrication modes, stylistic expressions, and formalist explorations of the material are shown. Variety, indeed, seems to be part of the point of the show – while the Leight collection has multiple holdings of the medium’s stars (Chihuly, Zynsky, Tagliapietra, etc.), only two are represented by more than two examples: the husband-and-wife team of Libenský and Brechtova´, and Richard Marquis.

The Speed’s installation makes a very compelling case for the importance of the donation and the medium. It is given breathing room and prominence seldom allotted to decorative arts. As the late Stephen Powell remarked, “…no other material can offer color so many ways to interact with space and light.†Glass is chemically a liquid, and the ductility of glass lends itself to the invention of a rich allusive language. While formal invention is constantly on view in the exhibition, an intriguing aspect of the show is its commentary on female identity and feminist issues, historical and scientific themes. Other themes could as readily be selected, but some of the most intriguing works center on these subjects.

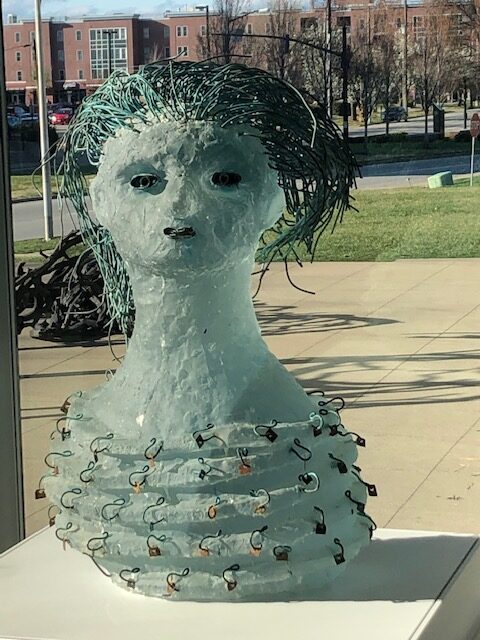

On the ground floor atrium, one of the first works a visitor encounters is the 250-pound solid glass bust of Ethel by Frank Murta Adams. Her frizzy copper wire hair and smirking facial features give her an imposing sense of formidable self-possession. Ethel is seen against a backdrop of Louisville’s Third Street: natural light pervades the translucent blue figure, who metaphorically becomes a Louisvillian in this installation. The blue is a menacing hue, like the color of the ocean before a major storm. Clearly, Ethel is a portrait of a woman not to be messed with.

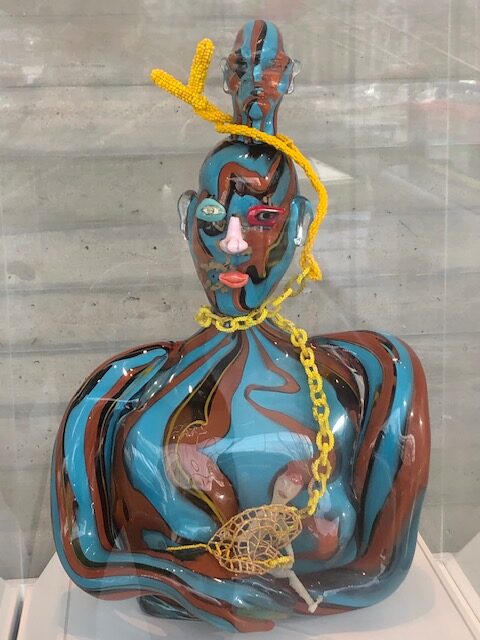

There are five other portrayals of females in the Atrium Gallery. Joyce J. Scott portrays victimhood rather than empowerment in Dizzy Girl, a blown glass figure with blue, brown, and yellow arabesque ribbons wrapped about her. She is bound by a yellow chain to a man sprouting from her head, and to a child held in her hands. The swirling bands of color provide an abstract equivalent to her plight. At the opposite end of the museum in the Loft Gallery, Silvia Levenson comments on the oppressiveness of women’s fashion in her forbidding red purse, Cactus, made of iridescent glass panels attached together with sharp protruding wires, and Cinderella, a mauve glass slipper with a menacing pin placed upward in the heel. Patrick Martin’s Untitled is a steel ring penetrated by twelve sandblasted green glass phalluses in various sizes, a metaphor of violence against women. Unattainable domestic perfection is the theme of Susan Taylor Glasgow’s Journey House, a small chamber with a single chair set atop a steep and narrowing staircase. Ennui and inertia are portrayed in Judith Schaechter’s stained glass assemblage, Clown Stinkabus. Schaechter, who once described herself as a “militant ornamentalist,†crowds a housewife collapsed on a chaise lounge with visually suffocating rug and wallpaper patterns and a table laden with bonbons. Schaechter, an innovator in stained glass technique, employs up to five layers of glass to obtain the color intensity she wants.

Adele Leight was a clinical social worker and later a marriage counselor, which may have influenced the selection of some works. Richard Marquis’s House with Horn is made of thin slabs of fused multi-colored glass, its palette reminiscent of Lifesavers or jelly beans. Does this improbable, surreal object connote the domination of a masculine presence? Marquis prefers to not answer questions about his work. Perhaps it’s significant that he left home at the age of fifteen.

Political themes are also a recurring motif in the exhibition. Richard Marquis’s enigmatic Potato Box 03-2 is a shallow Plexiglas box holding fifteen brightly colored blown glass potatoes. They are seen against a cardboard jigsaw puzzle of a thatched cottage. Marquis remarked, “It’s tricky to pull off an elegant solution using an intrinsically clunky object like a potato.†This time the palette seems borrowed from an ice cream parlor. Is this a rural idyll or an irreverent comment on the Irish potato famine that led to the death of one million people? A nail attached to the front of the box confounds attempts at easy interpretation.

Clifford Rainey, who was born in Northern Ireland, comments on the Irish “Troubles†with The Boyhood Deeds of Cu´Chulaind II. A transparent nude male is portrayed severed above the waist by a sheet of plate glass. The subject is an Irish mythological demigod, known for his violent and uncontrollable battle frenzies. The work was made in 1986, and although Margaret Thatcher and Garret FitzGerald had signed the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985, the bombings and assassinations continued.

The Czech artist team Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtova´ created the cast glass Empty Throne in 1999. The seat of the structure is slanted so that sitting on it would be impossible. A slit of light through the back of the sculpture intrudes on the sculpture’s mass as if to oppose the authority associated with the chair.

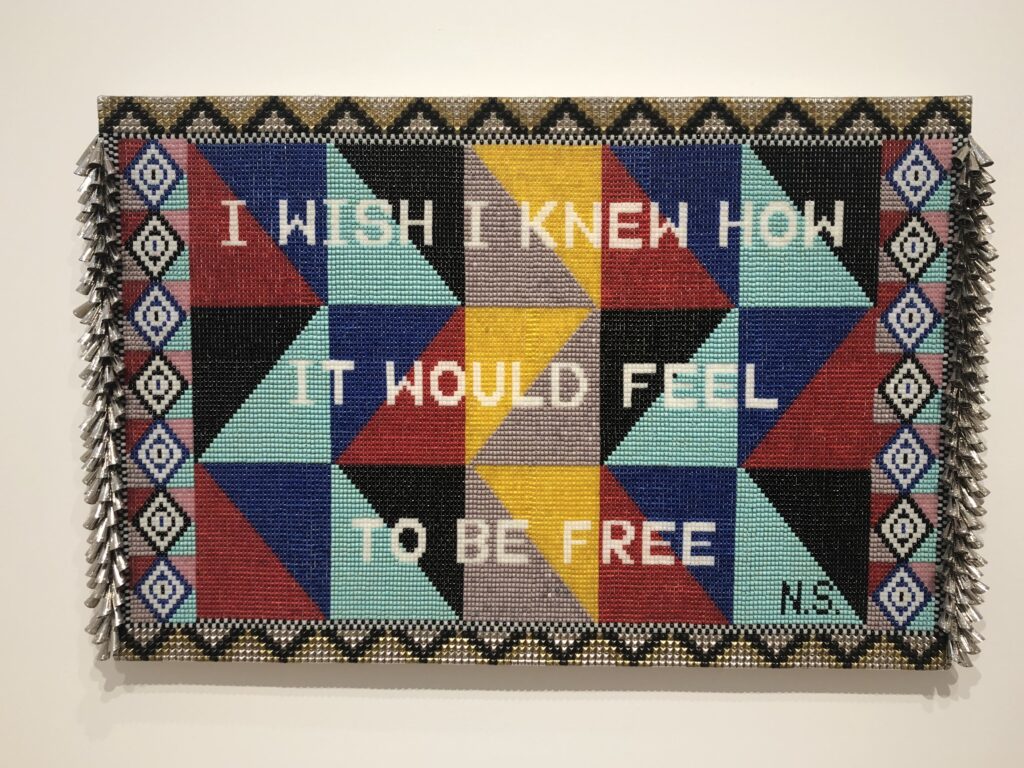

Jeffrey Gibson, an artist of Mississippi Cherokee-Choctaw ancestry, gives currency and universality to the Civil Rights anthem, “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free,†which Nina Simone recorded in 1967. In a typical Gibson cultural mash-up, the words are superimposed on a pattern of beaded triangles reminiscent of 19th century American pieced quilts. The borders evoke Plains Indian designs. The outside edges feature tin jingles used by Indian dancers.

Glass is associated with science through its use in optical devices and is associated with the occult in devices like crystal balls and black mirrors. Both associations are present in Libenský and Brechtova´’s Sphere in Cube and Cube in Sphere installed along the staircase in the Atrium Gallery. The Sphere in Cube provides an oculus into a cubist view of Louisville. Comparably, the Cube in Sphere on the middle landing turns views of passing traffic outdoors from parallel to perpendicular, and shrinks the outside world as if it were a terrarium.

The ability to absorb and incorporate environmental information, the tension between inner and outer spaces, the contrast between openings to illusory other realms and solid mass, scramble perception and fact.

“… [not an] artist’s junket†Rockwell Kent by April Surgent is part of her extended series of glass engravings providing an archival record of global warming and climate change. In 2013 Surgent worked at Palmer Station in Antarctica. The image is based on a time-lapse photograph of the sun’s track in November across the Antarctic sky. She has declared that her work discipline is based on “observation, conservation science and in-depth research.†The title is a quotation by Rockwell Kent, an early 20th Century American artist who worked extensively in remote locations in Canada, Greenland, and Alaska. In Antarctica Surgent made long exposure pinhole photos: “It’s a unique approach to seeing the way the world is and looking at time measured through light in a very different way than we see in our mass of digital photos.†Surgent continues, “an engraving in glass takes a passing moment and saves it as a tangible object.â€

My final example of thematic imagery in Collecting – A Love Story: Glass from the Leonard and Adele Leight Collection is Laid Table with Watermelon, Acorns, and Chalice by Beth Lipman. Five feet tall and over three feet in diameter, the assemblage is a profuse display of clear glass bottles, glasses, plums, a game bird, bread, a ladle, and other implements which both extend over the edge of the table and tower above it. Lipman’s work makes reference to 17th Century Dutch pronk (roughly translated as “show offâ€) still lifes that displayed a family’s most precious tableware. But 17th Century Dutch materialist pride in one’s most valued belongings was often accompanied, ironically, by Calvinist meditations on vanitas themes – the rapid passage of life, the emptiness of worldly possessions and pleasures, and the dangers of overindulgence. Poet Mark Doty has written about still life, “it is an art that points to the human by leaving the human out; nowhere visible, we’re everywhere.†Lipman’s work derives from art history rather than science, but evokes the central concerns of climatologists and ecologists about the widespread reluctance to give up fossil fuels or curb the use of plastics that pollute the oceans. Lipman’s piece shows off very well against the limestone walls of the central hall of the museum’s 1927 building, and gains added impact from its contextualized display next to the gallery housing 17th Century Dutch art.

Another review of this exhibition could as easily celebrate ovoid vessels exploring the relationship of color to form, or self-reflexive works about the nature of glassmaking, or imagery from nature, or geometrical abstraction, or aspirations to spirituality. Many of the works in the exhibition do all the things that craft is commonly thought not to do: provoke deep inquiry; problematize and interrogate the limits of metaphorical structures; create new modes of representation and abstraction; probe societal shortcomings; and in general, extend the visual dialogue along unforeseen pathways.