In Trees, an exhibition at Christ Church Cathedral featuring photographs by Tom Kimmerer and Guy Mendes, a simple conceit illuminates pressing issues of contemporary culture. Visitors to the cathedral are presented with an abundance of images showcasing the grandeur of Kentucky’s terrain and landscapes. On one hand, this exhibition is an opportunity to bask in the beauty of local plains, hillsides, and mountains. On the other, Kimmerer and Mendes draw upon their critical aptitude to reinforce environmental concerns around the globe, as well as photography’s temporal nature.

Guided by light and color, the compositions Kimmerer and Mendes generate are dynamic and arresting. In Monks’ Pond (2015), Mendes offers a viewpoint from a small body of water surrounded by towering limbs and foliage that recede into the scene. The ground the photographer must be standing on, however, creeps into the frame from the top edge, instilling a dream-like sense of place as the tall grass protrudes like a canopy. Utilizing the water’s reflection and expert cropping, Mendes fabricates a disillusioning image. Even photographs with more conventional presentation styles in the exhibit—such as one by Kimmerer of a silhouetted oak against a rural backdrop in Bur Oak Named Eilean—are striking given their emphasis on dramatic lighting and vivid hues.

Several of Kimmerer’s photographs are documentary, in that they take stock of the seasons and time, monitoring the cyclical tendencies of various plant life, observing trees and their surroundings. Boy in Snow with Trees, for example, records a wintry trek across a relatively barren expanse. The trees here are witness to all that is around them: the boy and his journey, the harsh weather, as well as their own process of death and rebirth. Similar to the trees, viewers are likewise able to focus and scrutinize the field of snow.

These types of photographs are visually quite stunning, as their settings seem almost too grand or painterly to be real. Kimmerer’s most conceptual output, though, are those that take a position of environmentalism.

A mammoth oak looms over a blue highway sign containing local food and gas options in Bur Oak at McDonald’s. Extruding from behind the tree, a pair of bright yellow arches beckon to hungry travelers. Kimmerer places his audience at an interstate exit, denoted by automobiles, a street light, and the advertising placard. On the sign are logos and trademarks of corporations that, to varying degrees, increase carbon emissions and damage our atmosphere.

The artist may be juxtaposing the scale of the tree against the comparatively microscopic business icons to emphasize the importance of keeping the planet clean. Even if this is not his explicit objective, the conceptual weight of the pairing holds.

This reading of Kimmerer’s photographs is linked to the idea that, with the acceleration of climate change, many of Earth’s landscapes, wildlife, and waterways are assuredly doomed. In a way, photography possesses the ability to prevent destruction from happening. Photographs freeze time, as it were, and present a version of the world that is specific to an exact moment, regardless of what may happen to erode its contents in the future. Theorist Roland Barthes recognized this feature of photography during the mid-twentieth century, going so far as to connect photographing to death, even when done as an act of preservation. By the end of his influential Camera Lucida (1980), he describes how the camera, in an attempt to keep something the way it is, initiates a phenomenon in which the resulting photograph indicates eventual death. Barthes states that, “Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.â€

For a composition that places oil industry emblems side-by-side with the physical natural world, Kimmerer’s Bur Oak at McDonald’s would stand as an ominous, if not inevitable, foreshadowing for the tree.

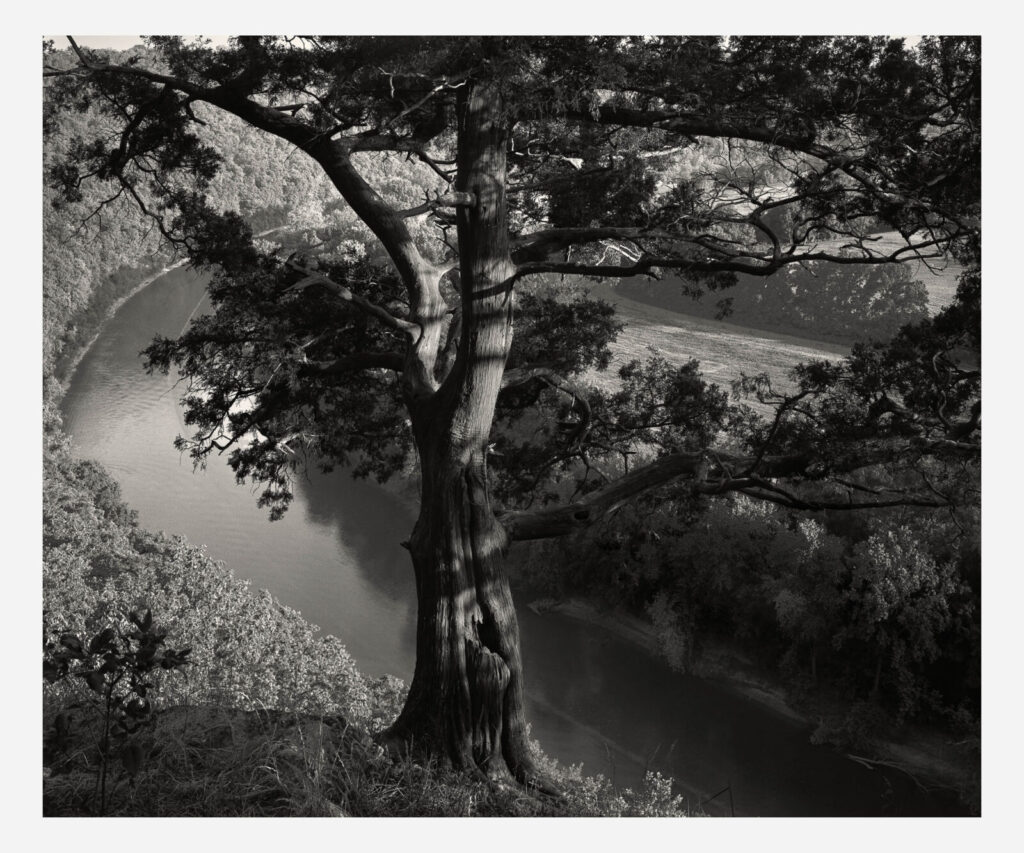

Within Trees, there are other works that also demonstrate photography’s relationship to death as Barthes describes. Mendes’ Buzzards’ Roost (1980) has served as a kind of insignia for the exhibition—the photograph is featured heavily on promotional materials and is by far the largest work. The framed print hones in on a tree looking over the Kentucky River and small canyon in Woodford County. Light beams through the tree’s leaves and stems so that their crisp shadows fall on the trunk, mirroring the direction and movement of the objects from which they are cast. The shadows and light combined with the immensity of the view make for a rather compelling image. According to Mendes, however, erosion and invasive species caused the tree to die, and such a scene can no longer be admired.

So, too, does Buzzards’ Roost fall under the guidelines laid out by Barthes. Mendes likely did not think that the tree would be entirely gone in less than fifty years, but by photographing it he especially designated it to ultimately die. Yet a photograph has that quality of recording things in a permanent state, only for its contents to continue to develop and grow outside of it. This anecdote makes one contemplate if or when other trees and plants in the exhibition will be eliminated from the areas viewers find them in.

The photographs in Trees populate the lobby area, main hallways, and multipurpose space of Christ Church Cathedral. Indeed, they beautify the cathedral in a way many other objects could not, though their social and environmental implications run much deeper than simply nice images to walk by. In addition to functioning as a testament to the splendor of our world, these works call each onlooker to think, act, and inspire on the planet’s behalf, before elements of nature are gone for good.

“Trees – Photographs by Guy Mendes and Tom Kimmerer” runs through October 27th at Christ Church Cathedral in Lexington.