by Paul Michael Brown ~

October 30-December 21, 2014

Christian Berst Art Brut (Klein and Berst)

95 Rivington Street, New York, NY 10002

The desire to communicate with others, to externalize thought in some way that is cohesive or comprehensible, is deep and universally human. Language provides a vehicle by which to do so, albeit in imperfect and often frustrating one. The 19 artists on display in Do the Write Thing: Read Between the Lines, the inaugural exhibition at Christian Berst Art Brut’s NYC location (helmed by Lexington’s own Phillip March Jones), engage with the necessity and inadequacy of language in the form of text.

The methods and materials employed by the artists in the show are wide-ranging, reflective of the disparate challenges encountered in the attempt to make oneself heard. In her introduction to the extensive catalogue that accompanies the show, critic and poet Lilly Lampe groups the works into three broad and overlapping categories: predictive or communicative, cataloguing or mapping, and asemic or wordless writing. It is worth noting that many of the artist’s work straddle multiple categories, or occasionally deal with themes outside these three most immediate groupings.

Of special interest to me were the works that fell into the last category. Asemic writing, by definition, is work that has no observable semantic consequence, at least in the way we are generally trained to ingest information from text. It is wordless, bypassing traditional methods of signifying through recognizable characters and instead uses forms reminiscent of language to communicate in novel ways. The asemic art in the show can be further divided into two modes, works that begin with legible text that is eventually obfuscated by other forms or marks, and works using marks that resemble text, but are nonsensical; in these works, meaning is either destroyed, erased, or not present in the first place.

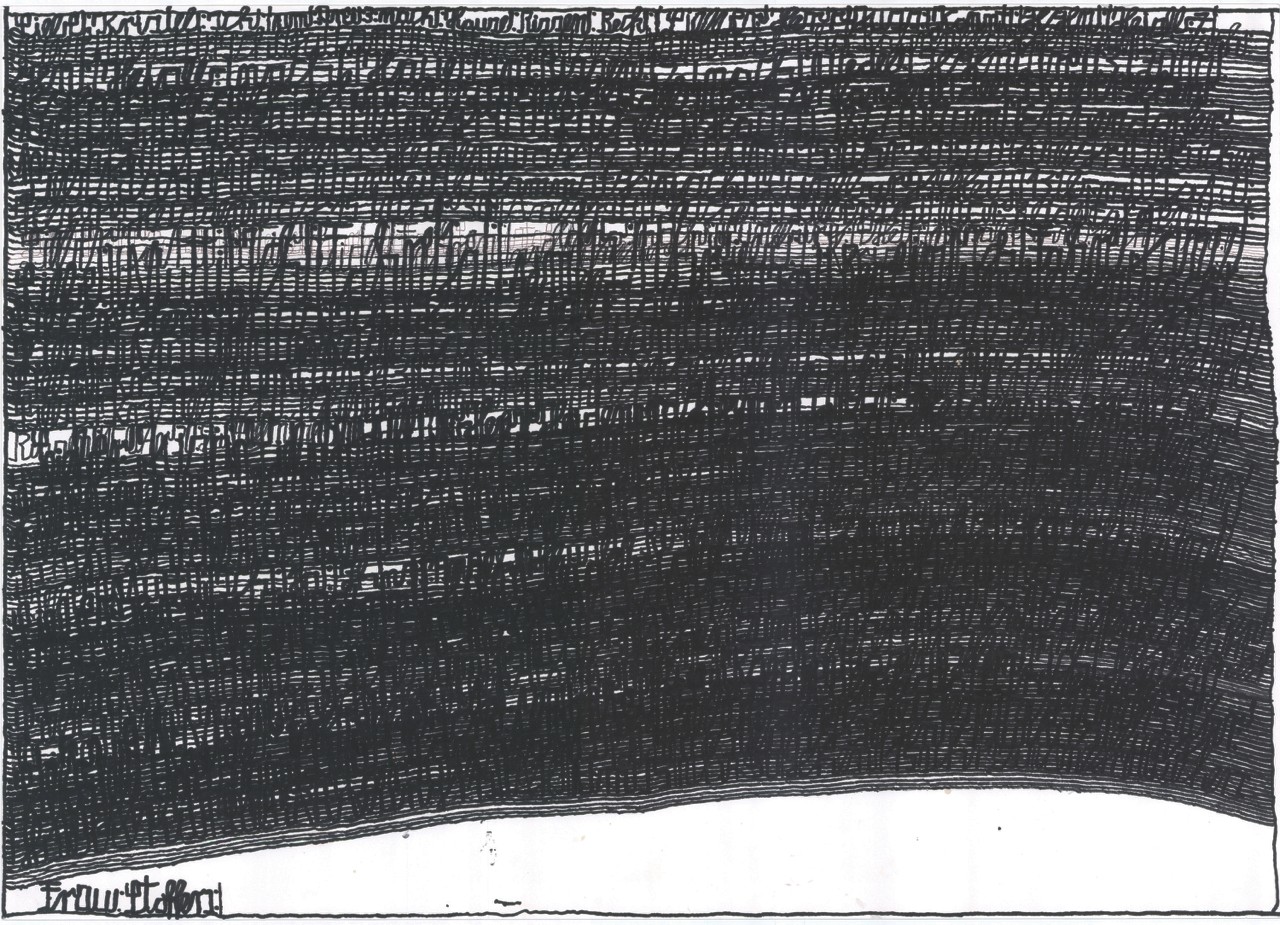

Harald Stoffers

Brief 160, 2009

Waterproofed Feltpen on cardboard

19.67 x 27.5 inches

Courtesy of Christian Berst Art Brut

Brief 338 (2014) by Harold Stoffers is an expansive work, spanning the vertical length of a thin wall towards the rear of the gallery. It is made up of tightly packed groups of parallel horizontal lines resembling muscle fascia that obscure text written in jerky cursive script, often addressed to the artists’s mother. The work is comparable to the structure of a musical staff, allowing reference to both written and musical language simultaneously, but not functional in communicating either in a traditional sense. It draws the viewer near with its intricacy. Varying densities of line, text, and free space pace the speed at which it is taken in. The accelerations, decelerations, and breaks encountered while ‘reading’ this work are not unlike those signaled by punctuation, paragraph, and page break found in more traditional texts.

Beverly Baker

Untitled, 2014

Ballpoint pen on paper

16.25 x 23 inches

Courtesy of Christian Berst Art Brut

Likewise, Beverly Baker, of Lexington, obscures her original text, but to an even greater degree. Baker’s works in ballpoint pen start as legible writing, copied from a small number of source materials. These fragments are layered one upon the other until the paper is completely covered and the content of the text is rendered moot. Baker’s methodology is analogous to that of Zhang Huan in his work ‘Family Portrait’ (2000), a series of photographs tightly cropped in on his own face, increasingly obscured by the names of his family members until his visage is entirely blacked out by ink. Baker’s use of ballpoint pen, coupled with the force of the marks utilized, form divots and peaks, creating a variegated and even three dimensional abstract landscape of dense color and surprising intensity, a suggestion echoed in the horizontal presentation of her work in the show.Â

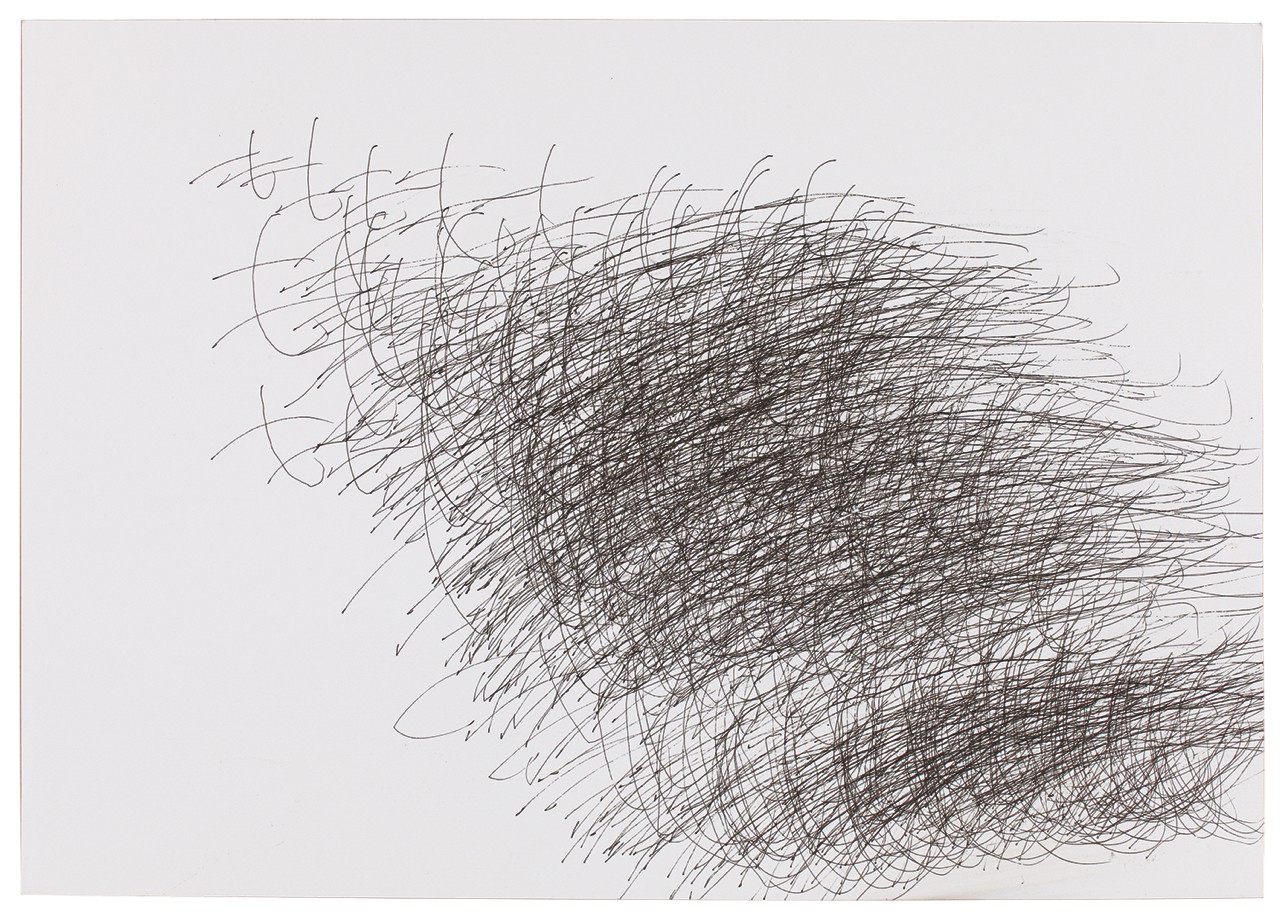

Yuichi Saito

Mo letter (Doraemon), circa 2005

Ink on paper

15 x 21.5 inches

Courtesy of Christian Berst Art Brut

Yuichi Saito utilizes superimposition in similar ways to Baker and Stoffers, repeating the titles of his favorite TV shows over and over until they converge into densely populated clusters of characters against a stark white background. The effect here is a bit like what occurs when one says a single word aloud repeatedly until it loses meaning and begins to dissolve into its phonetic constituents, warped and distilled by repetition .The work is also an exercise in documentation, as Saito creates the each piece the day that the show airs. They are restrained in composition, the clouds of text compliant in the chaos they make up, bearing mild visual reference to animal herds, birds in flight, and other natural phenomena (linking them to the grandiose landscapes of Xu Bing rendered in Chinese text).

Â

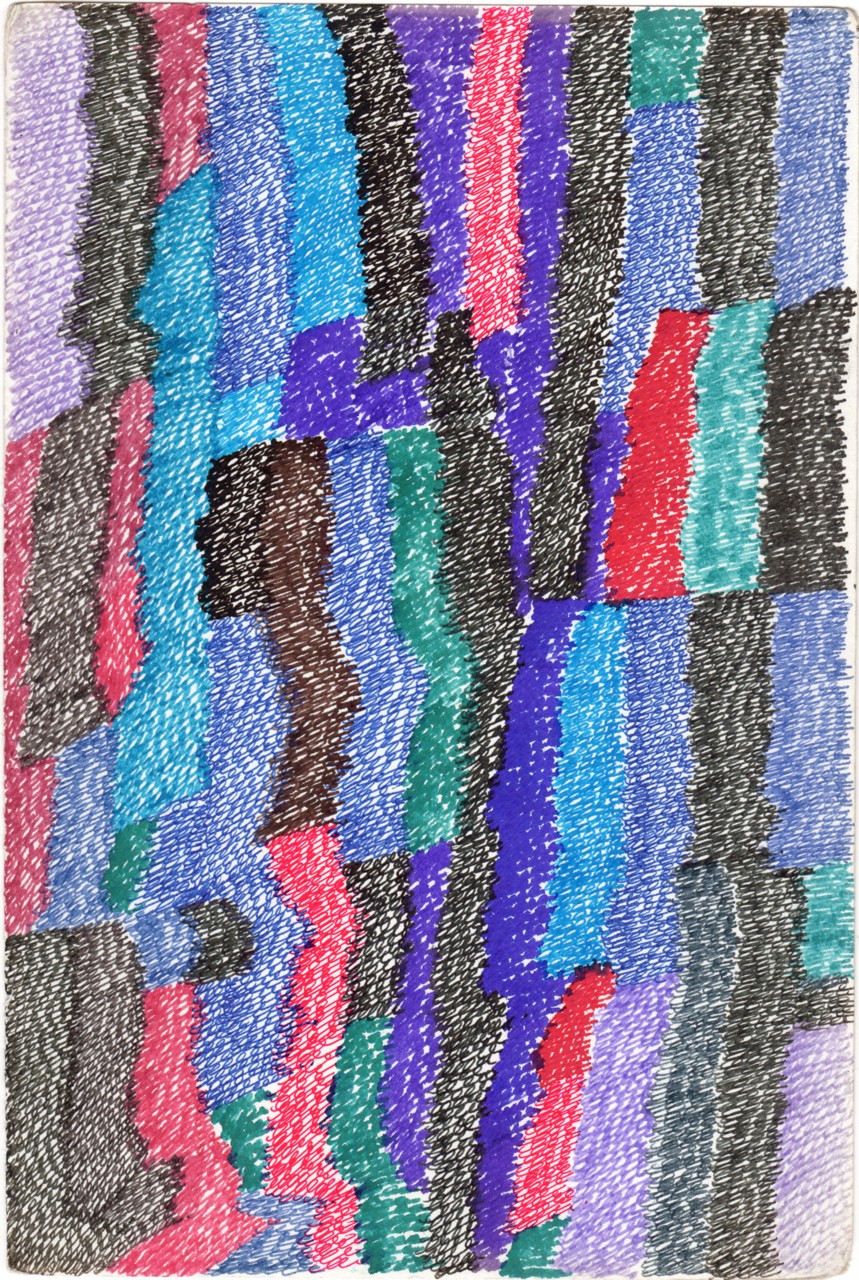

Jill Galliéni

Untitled

Colored ink on paper

9.45 x 6. 3 inches

Courtesy of Christian Berst Art Brut

Blocks of differently colored inks made up of lines of cursive like curley q’s make up Jill Gallieni’s work. According to a statement provided by the gallery, she began to create these works as prayers with meaning only discernible by her, addressed to Saint Rita, patron saint of lost causes. The brightly colored inks conform to blocky shapes often configured into abstract compositions that look somewhat like crochet or weave. The more heavily fragmented pieces bear unlikely but adequate resemblance to Coogi sweaters, a material used by Jayson Musson (aka Hennessy Youngman) in some of his recent work. The lines of text are continuous, interrupted only by the limits of the page. Gallieni’s prayers are ceaseless, constrained, and intensely private.

Although not in the way we expect, these works communicate strongly. Within them, compulsions to express, document, copy, obliterate, and even to enact divine intervention, can be found, all without the utterance of a concrete word. Here we find language, stripped of its explicit functionality, being used as a completely experimental and untested tool. These artists operate outside of normal syntax to establish new patterns of (a)textual expression, creating enigmatic and nonsensical readings that provide openings for us to push what and how we communicate, a necessary and admirable endeavor.