As its name implies, Alison Saar’s Breach, currently on display at the UK Art Museum, offers insight into the collective memory of tragedy through ruptures in the narrative strands of history that are equally lyrical and horrifying.

While an artist-in-residence in New Orleans in 2010, Saar’s experience in the still-ravaged city, five years after hurricane Katrina, provided the initial impetus for a body of work that investigates the historical and cultural linkages between disaster and African-American experience. The works in Breach draw from an event nearly eighty years before Katrina, the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927. Saar’s works attempt to explore the way this disaster, like Katrina, had an obscenely disproportionate effect on poor African Americans. Most African Americans were prevented from evacuating affected areas, forced to seek refuge on levees, and were forcibly conscripted in rebuilding efforts. The long-term effects of this disaster and its outcomes were not simply material, but had broad and enduring implications on the shared cultural experiences of African Americans.

Entering the main gallery, the walls are lined with portraits whose figures, their eyes pupil and iris-less, stare out at the audience in the throes of ecstasy and terror. Water rises around them, they gather up possessions above their heads as their bodies, some clothed and some nude, are variously submerged in the tide. Many of Saar’s works feature charcoaled images on found objects such as sugar sacks, denim scraps, drawers, and trunks, that dually function as physical objects and images and so take on iconic and even fetishized importance within Saar’s visual lexicon. Not unlike the practice of her mother, artist Betye Saar, Alison Saar’s assemblages blur the distinctions between memory and experience embodied in physical objects extracted from practical use and installed in the gallery.

In Breach (2016), the exhibition’s namesake and centerpiece, Saar hammered together tin ceiling tiles to form a life-size figure crowned with possessions saved from floodwaters. The figure, drawn from the mythological imagery of Greece and the African Diaspora, becomes an entirely new mythic sign, one though which Saar attempts to represent history as embodied experience.

In fact, all of the works in the exhibition display direct traces of black bodily experience of disaster. Beyond the Great Flood and Hurricane Katrina, works like Hades D.W.P. II (2016) explore other systemic breakdowns that have disproportionally affected African American communities, namely the recent Flint, MI water crisis.

A shelf displays five large glass containers that hold vile looking liquids, eerily lit, whose fronts are etched with black body parts. The etched figures appear to drown in their glass enclosures, an effect that recalls both the violence of enslavement and the misery of black experience in light of persistence of racism and poverty. Saar’s works, that blend and blur the distinctions between both media and bodily experience, portray these recurring motifs of racist subjugation in a frank and visceral way. Muddled with mythological significance, words like “Hades,†“Lethe,†or “Mami Wata,†an African water spirit, tinge the works with a cosmological gravity that penetrates deep into the present. Death and suffering are present in the multitudinous signs Saar deftly weaves and layers together.

The exhibition, split into two main spaces, establishes the content of Saar’s works beyond their physical presence, but extended into history and its practice. Saar draws on both the experience of the Great Flood and the effect it had on black culture, as it imbibed art and music in the 1930s and beyond with the traces of the Flood’s disastrous effect on black consciousness. Saar also reflects these traces back onto her works as well. Sluefoot Slide (2015) and Muddy Water Mambo (2015) both feature black figures, painted on bits of sacks, cloth, and denim, dancing and gesticulating in rising water, their ambivalent reactions to a disaster unfolding around them perhaps not uncommon to communities who have long suffered violence and oppression. Such ambivalence often manifested itself in the music of the Blues, traces of which can be found in Saar’s imagery.

In the second gallery, a film plays on a screen, where Saar narrates historical accounts of the Great Flood interspersed with explosive footage of her studio practice. Like the musicians and artists of the 1930s, Saar also contributes to the slippery space where art, history, and experience mingle. Printed works, which constitute a large portion of the exhibition, exemplify this practice. In fact, a majority of the works might be classed as prints, as they present the viewer with surfaces imprinted with the historical and bodily experiences of African American communities devastated by watery disaster.

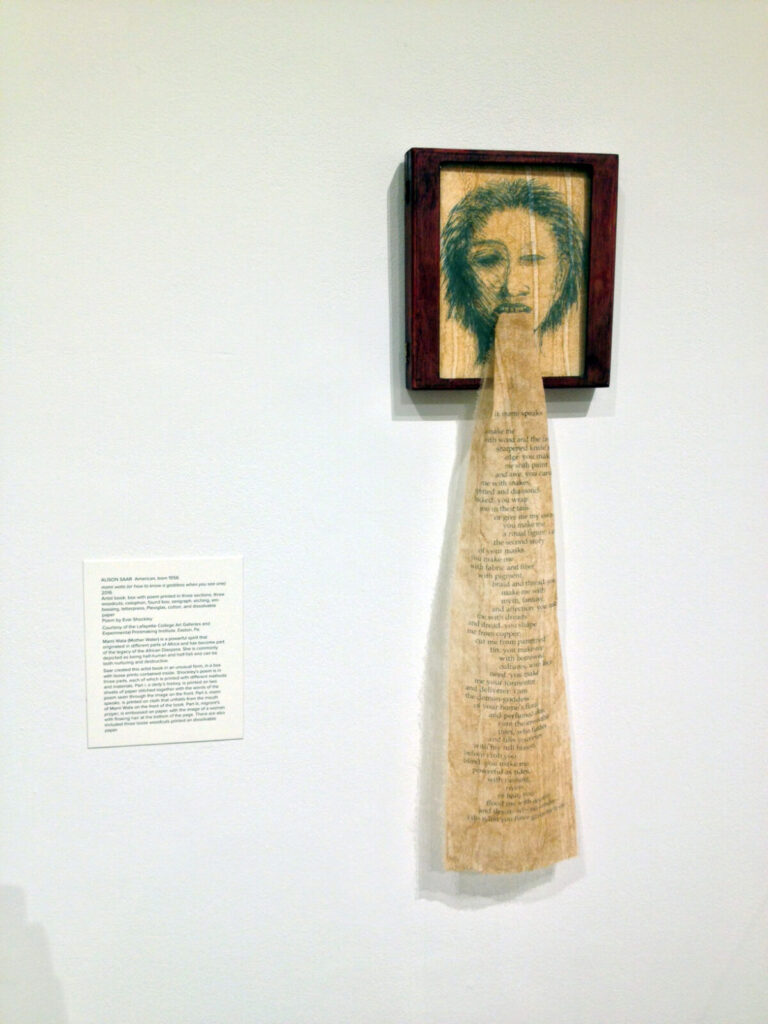

Another kind of narrative chronicle hangs across from the screen where the film plays. mami wata (or how to know a goddess when you see one) (2016) takes the form of an artist’s book, the pages a single long sheer sheet that flows out goddess’s mouth. It is this speech, the markings of experience on history and culture, that Saar’s work so forcefully elucidates.

Saar’s success is not just in the works themselves, but in the way she investigates the language of black cultural experience that has been marked through a history of violence and destruction. Standing in front of the monumental Breach, one cannot help feel the weight of both the colossal load the figure bears and the significance of history embodied and marked on its surface, transformed into an icon, and speaking its experience.

Photo Credit: Joel Darland