In a car you’re always in a compartment, and because you’re used to it you don’t realize that everything you see through that car window is just more TV. You’re a passive observer and it is all moving by you boringly in a frame.

On a cycle the frame is gone. You’re completely in contact with it all. You’re in the scene, not just watching it anymore, and the sense of presence is overwhelming.

Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Sarah Lyon’s show of thirty-two photographs at the University of Louisville Photographic Archives Gallery illustrates a motorcyclian world view: the work uncannily puts the viewer into the pictorial realm, in a relationship to the subject that transcends the vicarious. Travel photographs but in no way a travelogue, Lyon opens her experience to the viewer while ironically remaining very much the creative personality occupying these images. Spanning fourteen years of the artist’s work, Lyon describes the work as a “personal investigation of what happens with artistic process as life evolves and changes, while embracing the inevitable ebb and flow of inspiration and motivation.”

In that pursuit, Lyon subverts normative orthodoxies, revives the rebel ethos of the motorcycle rider, celebrates alternative lifestyles and serves as a road-wise guide, especially to “areas in the American west that draw and intrigue me emotionally, spiritually and aesthetically.”

Consider Bonneville Salt Flats (Utah Phone), 2011. An open phone booth is centered in the photograph: below is a band of asphalt and a culvert, and beyond, a band of dirt, the luminescent salt flats, far off mountains, and cumulus clouds above. The phone booth enclosure is a chamber opera of light, shade and reflection: the reflections against the front plate and keypad, the mottled light through the side of the booth enclosure, sunlight falling across the front of the booth, and the curved wire cord to the handset, provide a frontispiece to the vast expanse beyond.

USWEST is the name of the telephone company and the implication is that this is indeed the true American west – vast, desolate, solitary, and silent. Sky takes up half of the 30 by 30 inch image. A series of color and shape rhymes reiterate the sense that human communication by phone is irrelevant or futile in this context: the pavement gray echoes the gray of the distant mountains, the blue of the phone sign is a washed out version of the sky beyond and the reflections on the front plate are pearlescent like the clouds. The shadow of the phone booth is suggestive of a squat phalanx warrior holding a shield, a shape repeated in the irregular concrete and drain on the left.

All are belittled and left defenseless by the scale of the landscape. At first a minimalist composition with its deadpan centering and regular bands of topography dropping back into the distance, Bonneville Salt Flats (Utah Phone) is convincingly not simply a place recorded by Lyon but a complex meditation on the folly of the manmade and mechanical in the face of the grandeur of nature.

Two self-portraits are comparable in the use of deep perspective to draw the viewer in. First Storm, Minnesota Self-Portrait, 2003 shows Lyon with her back to the camera braving an approaching storm. On the horizon is a farm and distant band of trees. Rowland Barthes described the salient detail in a photograph as the punctum: “a photograph’s punctum is that accident which pricks me but also bruises me.” A red X at the perspectival endpoint (apparently headlights reflected in wet pavement) is the punctum in this image – as far forward in Lyon’s journey that the photograph records. In effect we are told, “this is the photographer, this is her motorcycle, this is her direction, this is the country she is traversing.”

Salt Evaporation Plan Road, 2017 is comparable in showing the photographer from behind, this time with a cord trailing in the foreground to the unseen camera. Sky, again, is half the image. Lyon is deeper into the foreground than in the Minnesota photograph, suggesting an appropriation of the wide open desert scrub land as part of her consciousness and identity. Lyon juxtaposes herself with the distant end of a gravel road.

“Vanishing point” in Swedish is “flyktpunkt” – which may carry implications of flight or escape: ominous foreboding, intimations of mortality or future passage of time is implicit in this portrayal, an altogether different kind of punctum. (It may also be pertinent that “vanishing point” is a recurring theme in motorcycle safety courses, indicating the limits of the rider’s knowledge. By focusing on the point where the asphalt meets the horizon, the driver has the maximum time and maximum distance to react to hazards or surprises). The shutter cord is the viewer’s point of entry here as if we were collaborators in the making of the photograph. Again, Sarah Lyon brings us inside the frame.

A third self-portrait is a recreation of Danny Lyons famous 1966 shot of a member of the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club, “Crossing the Ohio.” Picturing herself (by collaborating John Nation and Maggie Huber) on the Kennedy Bridge in Louisville is a declaration of affiliation with older norms of bikeriders’ free spirits.

Lyon may be best known for her series of photographs of women mechanics, a feminist response to the pin-up calendars that still appear in car repair shops. Jessica Dulong, Fireboat Engineer, Hudson River, NYC, 2009 portrays the engineer and author at work in command of the rich complexity of the engine room. If one includes the self-portraits, over a third of the 32 pictures in the exhibition are portraits of people acting in their professional setting: fireboat mechanic, conceptual artist, visual artist and chainsaw mechanic, blacksmith, performance artist , musician, D.J., and motorcycle parts dealer. Lyon works in the tradition of the “portrait d’apparat,” a baroque practice of depicting people exercising their profession.

Early American portraits, such as John Singleton Copley’s 1768 rendering of Paul Revere holding a teapot is notable for showing the artist in his shirtsleeves, his engraving tools in front of him. The silversmith appears with none of the trappings of power and respectability characteristic of 18th Century portraiture. Even more dramatic in its democratic implications is John Neagle’s 1827 full length painting of “Pat Lyon at the Forge.” (No relation to the artist).

A successful businessman and inventor, Pat Lyon began his career as a blacksmith, and commissioned a depiction of himself in that profession, mallet in hand. Lyon insisted that his portrait include a view of the prison in which he was wrongly incarcerated in his youth. Sarah Lyon continues that tradition and evades the voyeurism and class consciousness that sometimes afflicts documentary practice. She does so by either totally evading the formality of the traditional artificiality of posing, or in contrast, heightening it with improbable settings – for example, D. J. ‘Jumbo Shrimp’ in a sailor suit standing in a derelict boat, or performance artist ‘Narcissister’ upside down on a kitchen cabinet disporting masks. Again, borders disappear.

Traveling with Bill Burke, 2012, is a portrait by synecdoche of the veteran photographer and the character of his company on a road trip – lens, wallet, cameras, pistol, magazine, beer bottles, glasses, paper cup, radio and telephone on a motel bedside table, sum up the experience with inventorial aplomb.

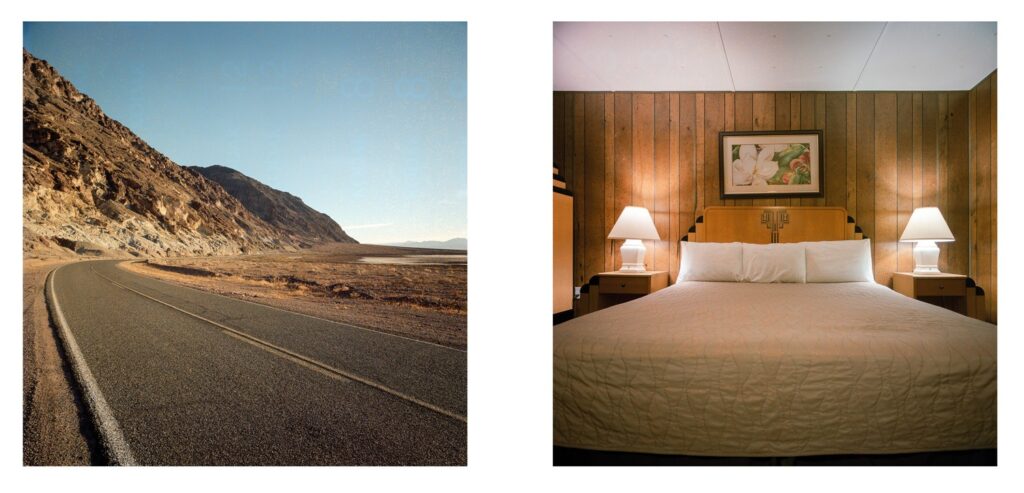

Motels also feature in a diptych Atomic Inn, Beatty, NV and Badwater Road, Death Valley, CA, 2017. Again Lyon stands in the road and brings the viewer inside the frame. The yellow brown rock formation on the left of a curved road in Death Valley has its color match in the knotty pine paneling and Navaho-Deco headboard in the motel. The distant white jet contrail above the landscape is paralleled by the white of the pillows on the bed. The crepuscular light of sunset has an echo in the twin bedside lamps: the white plug on the left is the punctum, emphasizing the artificiality of the interior illumination.

What is remarkable about Lyon’s work is not what she has seen but how she has shared it. The trip provides the overall narrative. Lyon makes it participatory, providing access to her forceful and independent vision.

Sometimes it’s a little better to travel than to arrive.

Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Drive: Photographs of Sarah Lyon is one of fifty-three exhibits in this year’s Louisville Photo Biennial. Lyon’s work may also be seen as part of Open Studio Weekend, 12 to 6, November 4th and 5th, at Quadrant, 380 Missouri Avenue, Jeffersonville, IN 47130.

Lyon is a member of the Kentucky Documentary Photographic Project.