About two hours south of Atlanta in Buena Vista, one of America’s prominent folk art destinations and environments showcases brightly painted buildings, walls, and other structures, decorated with iconography borrowed from religions and spiritualties of all kinds. It is called Pasaquan and was created by artist Eddie Owens Martin (1908-1986), also known as St. EOM (pronounced like the Hindu “Omâ€).

At Institute 193, Pasaquan is enshrined and sampled in an exhibition called “St. EOM: Pasaquoyanism.†The organization has transformed its gallery space to offer a taste of Martin’s compound, most vividly by painting the longest gallery wall sky blue, radiating to passersby on Lexington’s North Limestone street where 193 rests. The gallery is adorned with paintings, drawings, and other objects that, in tandem, emanate the kind of images, craftsmanship, and experience visitors to Pasaquan may encounter. As a system, the artworks in “St. EOM†function less as a presentation of select examples of an artist’s output and more as an archive or record of their creative trajectory. Â

According to the exhibition statement, Martin moved to New York at the age of 14 and spent his early adulthood working as a hustler, gambler, oracle, and drug dealer. He was sent to the Federal Narcotics Prison Hospital in Lexington in the early 1940s after it was uncovered that he ran a small gambling and drug enterprise out of his home in Harlem. Martin began painting frequently upon returning to New York in 1943, notably creating scenes of ancient cultures out of discarded woods and other materials, but also developing a traditional skillset, as illustrated by the presence of a small oil painting of a home interior.

The inspiration for his paintings derived from visions he had experienced since his twenties. In them, Martin claimed to speak with spirits who took the form of tall, elongated, androgynous humanoids. These beings appear in many of the works at 193; they have ambiguous skin tones and hair colors, are depicted in groups, and, in some form or other, are surrounded by geometric patterns. These figures instructed Martin to return to his native home of Georgia in 1957 to build Pasaquan, which still functions today and is scattered with shrines, pagodas, temples, and other structures.

The culmination of Martin’s visions, his life experiences, and the construction of Pasaquan led to the formation of Pasaquoyanism, a religious doctrine that combines elements of Eastern and Western faiths and spiritualties from multiple centuries. Perhaps more of a lifestyle than anything, Pasaquoyanism—the exhibition’s namesake—is succinctly documented in “St. EOM.â€

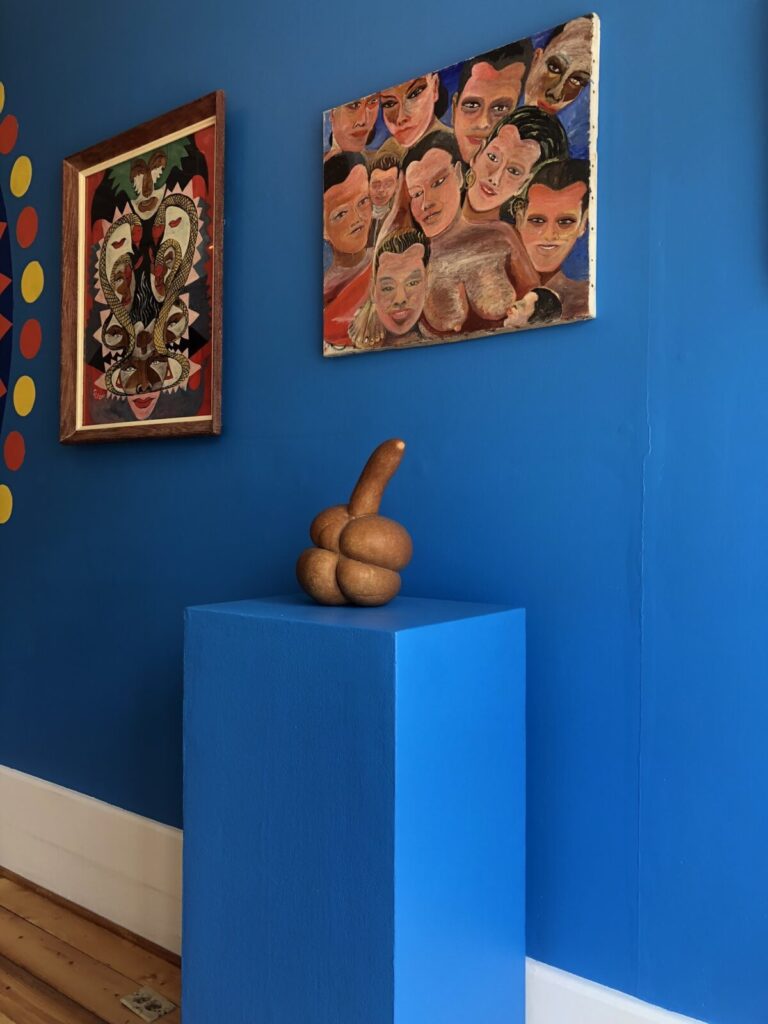

The notion of the archive is bolstered by the unifying power of the blue wall. Two pedestals are placed against it are also painted blue, practically going unnoticed if not for the single objects that sit atop each: a beaded necklace with alternating wooden cylinders and spheres, and a gourd whose bulging and elongated shape could easily spur a critical reading with sexual implications. Both objects are presented as if they were votive. In concert, they, as well as the nearby paintings and the bright wall, embody the kind of symbolism and participatory elements of Pasaquoyanism.

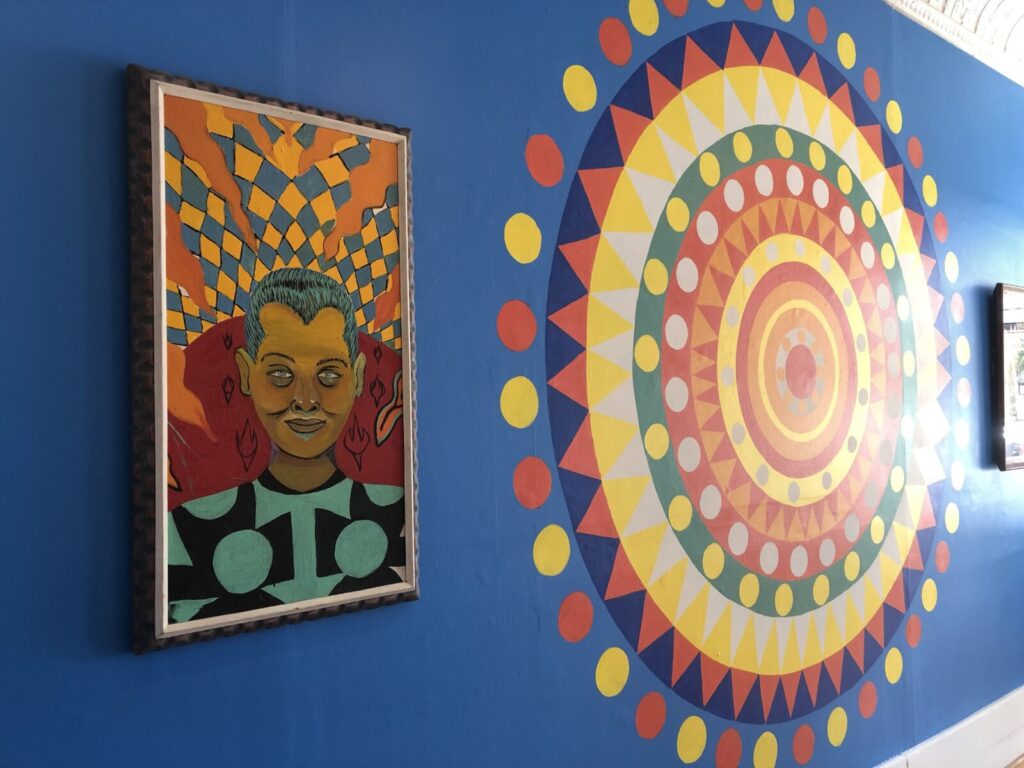

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a mesmerizing, brilliant constellation of dots, diamonds, triangles, and rings orbiting around a single vermillion circle, the full diameter of the work as tall as the blue wall on which it is painted. It is a beacon for visitors, indicating the arrival to the sacred land. The pattern is reminiscent of Mesoamerican calendars, marking the passage of time cyclically and precisely. Despite most works in the exhibition lacking dates and titles, the mural is the conjoining factor in “St. EOM,†connecting all themes, palettes, and subjects. The mural amplifies the spirit—indeed, Martin’s spirit—that runs through every object on display.

The mural is a duplicate of another located at the Pasaquan compound. These kinds of images are rampant there, populating the interiors and exteriors of buildings, concrete fences, totems, and a vast array of other surfaces. The design at 193 may be unique, but it is far from the only mandala-like shape Martin painted. Yet its singular nature in the gallery may prompt a moment of pause for viewers, not only due to its size and striking color. With three paintings and a pedestal to either side, the mural is the moment of balance within the exhibition. It is the equalizer. Without it, the works included in “St. EOM†would seemingly lose their grounding as interconnected revelations.

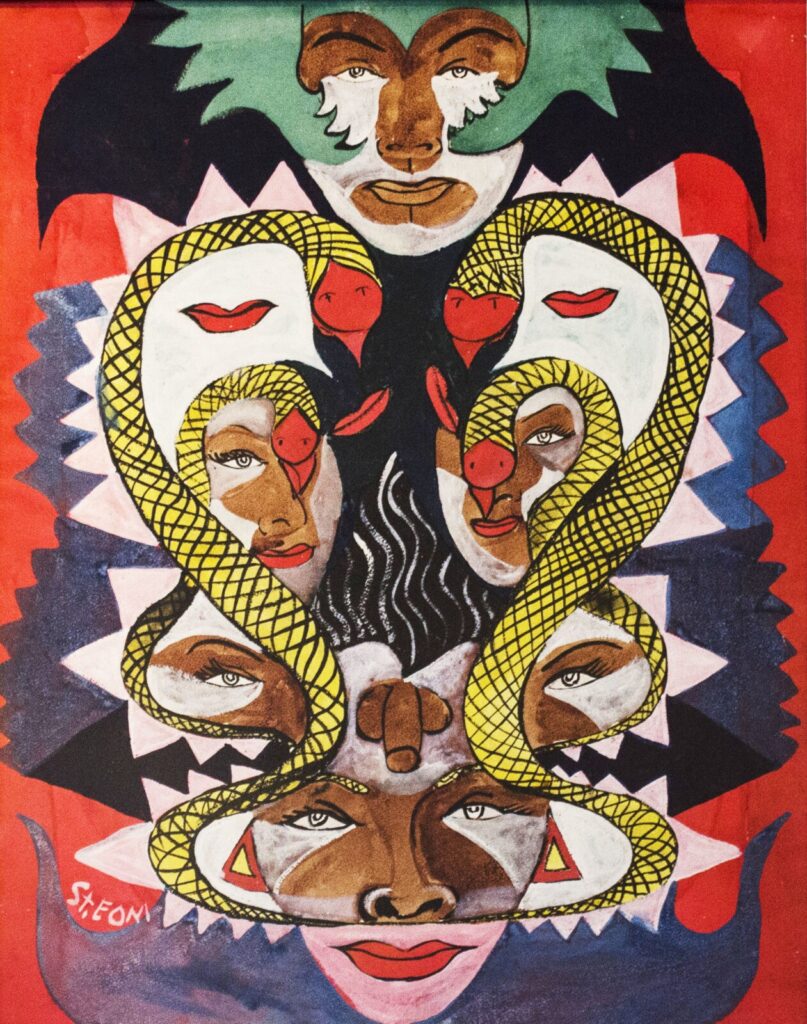

The figures that visited Martin in his visions are described in many paintings in “St. EOM,†including in a red and violet dreamscape containing six incomplete faces, four snakes, four floating pairs of lips, and a penis that appears to be attached to a figure’s forehead. The work carries obvious phallic invocations. Yet the symmetry, color, repetition of the same facial features, and association with animals suggest this figure is deeply connected with the world around them—a deity, perhaps. It could be that they are someone Martin knew or dreamed up. In any case, the portrait functions as a representation of a force larger than a single human—could this be an embodiment of nature that Martin offers? If it were, the fleeting qualities of the painting, such as the isolated eyes, lips, and genitalia, likely imply that the figure is not wholly human and thus something else altogether.

Another figure is the focus of a different painting; their gender, ethnicity, and age are undetermined. The shirt they wear possesses a rigid interspersion of triangles, rectangles, and circles in bright turquoise that matches the color of the figure’s hair and pupils. They are haloed by fire-like streaks of orange and interlocking diamonds.Â

Unlike the six-faced painting, this work peers at the viewer, as if it were inviting them into Pasaquoyanism, much like a separate painting of three sitting figures in a pyramid formation. Both paintings are of figures who acknowledge the viewer with their stares, ignoring the setting—whether atmospheric or scenic—in which they are placed. Visitors to Institute 193 are their main focus, and they seem intent on drawing them into their world. These paintings, like “St. EOM†itself, are a preview of what Martin’s religion looks like and how it visually behaves—as a lively, enigmatic mode of living, made manifest in the beings and landscapes Martin portrayed.Â

“St. EOM: Pasaquoyianism†is on view until June 22, 2018 at Institute 193 in Lexington, Kentucky.Â

Â