As you enter Institute 193, you come face to face with Kiki. The portrait depicts a voluptuous woman lounging in a plane of matte black nothing; her long brown hair accented by caramel strands. She is nude, careful attention paid to the way light and shadow travel across the flesh of her thighs, pubic area, stomach, breasts, chin, and face. The most striking parts of this image are her red-lipped smirk, as if she is caught in mid-laughter, and her cat-eye sunglasses. Her shades and makeup serve as the only clues to the viewer of who she might be. She is laid bare yet still withholds information from the viewer. Because we cannot clearly see her eyes, her gaze belongs to her. Why is she smiling? Could she be playing a joke on the viewer? This small painting serves as an introduction to Patrick Smith’s 2020 show “The Intimacy of Othersâ€. The show is comprised of a series of portraits that span Smith’s career and are exemplary of his contemporary academic realism. However, to try and label Smith is to try and name the ineffable. Smith’s set-up delivers a different punchline, often one you weren’t expecting.Â

As Institute 193 director Elizabeth Glass writes in the press release for Smith’s show, “Patrick Smith’s paintings appear to capture glimpses of personal, private moments meant to be seen by a single person, or no one at all.â€Â

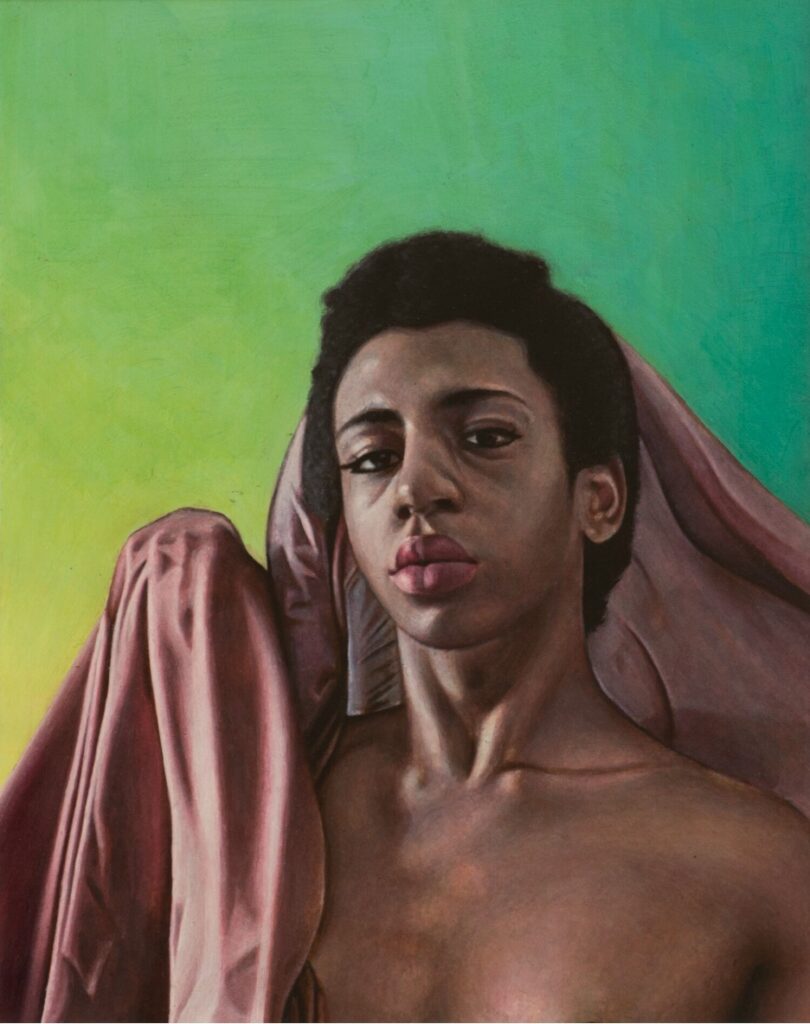

Smith’s portraits challenge the viewer to see his subjects in another way. They are his friends, people who (if you’re a Lexingtonian) you have probably passed on the street, seen at their jobs, or followed on Instagram. I first became familiar with Smith’s work when he painted a portrait of my friend Armani. Armani, a 2018 painting, depicts the titular subject nude save for a pink-puce shroud draped around their head and shoulders. The draping invokes something virginal about Armani, implying a certain Madonna-esque status. Like many of Smith’s paintings he relies on accessories and decoration to give clues to the viewer about who they are. Armani’s eyeliner serves as a hint about who they may be beyond the frame of the painting. Unlike Kiki, Armani gazes directly into the eyes of the viewer. Their face held in a soft expression that is at once seductive and oppositional, Armani dares the viewer to look, and they look back.

In bell hooks’ 1992 collection of essays “Black Looks: Race and Representation†she coins the term “Oppositional gazeâ€.

“Looking at films with an oppositional gaze, Black women were able to critically assess the cinema’s construction of white womanhood as objects of phallocentric gaze and choose not to identify with either the victim or the perpetrator.†(hooks, 1992, 122)Â

In Smith’s portraits his subjects confront the viewer, they are seductive, vulnerable – and by exuding these qualities, powerful.Â

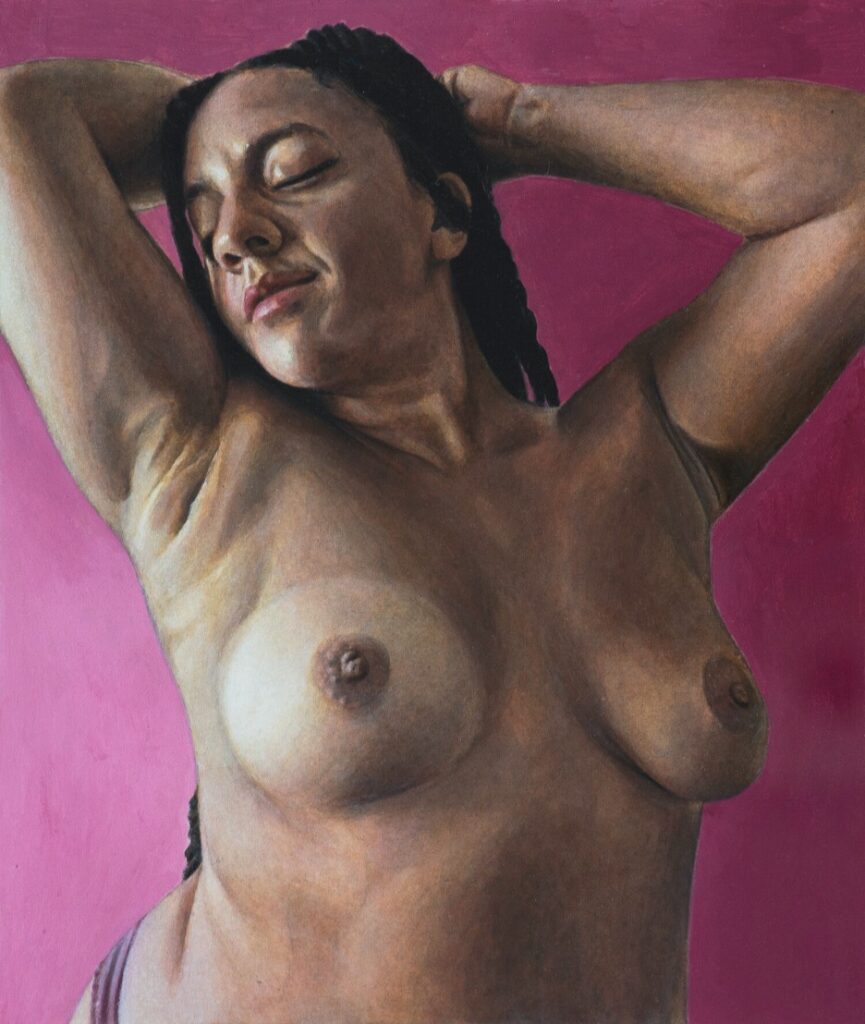

Two of the most compelling images in the show are Armani II and Alyssa II. Like Kiki, these images depict a playfulness. So rarely do we see images, or hear stories of, Black leisure, pleasure, and joy. In Alyssa II the subject has her hands above her head, her hair in twists cascading down her back, barely visible to the viewer. Her eyes are closed, and she smiles. The light caresses her face and side. Although she is positioned in a color field of magenta, the viewer could easily imagine her resting on a bed, a sofa, or lying in the grass on a warm summer day. Her guard is down, she is not threatened, she is safe.

Following the 2020 murder of Breonna Taylor by Louisville Metro Police Department officers Jonathan Mattingly, Brett Hankison, and Myles Cosgrove, global outcry about the systemic mistreatment and killing of Black women made headlines and ignited engagement in Black Lives Matter and the defunding of police. In Alyssa II we see something so rarely depicted in the media, a Black woman at peace.Â

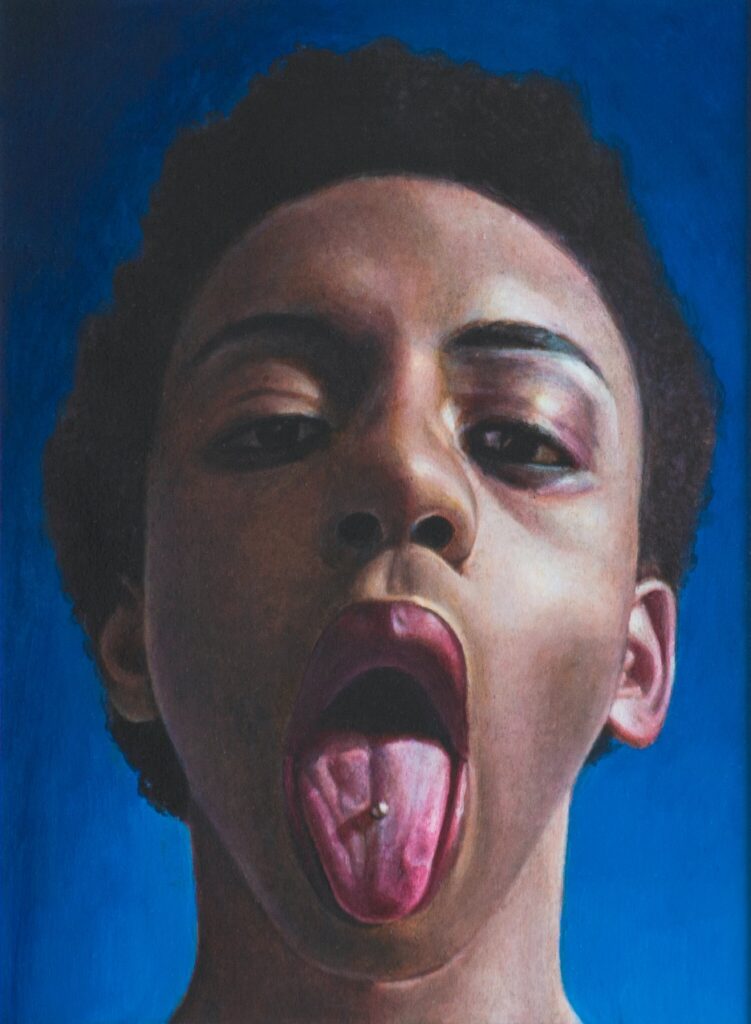

In Armani II, we are treated to some of the playfulness present with Smith’s work. Gone is the virginal Madonna from the previous picture of Armani, now in a sea of royal blue we see Armani up close and personal. Their tongue is stuck out as if to tease us, or express disgust. The focal point of the image is the small surgical steel bead shining from the center of Armani’s tongue. While many of Smith’s subjects bear tattoos and piercings, I find the single visible tongue piercing in Armani II to be one of the most striking aspects of the image, and the show. This single piercing positions them as rebellious, alternative, unique; however, if they close their mouth this insight to their character is lost. Armani II dares us to look and see what’s hidden.Â

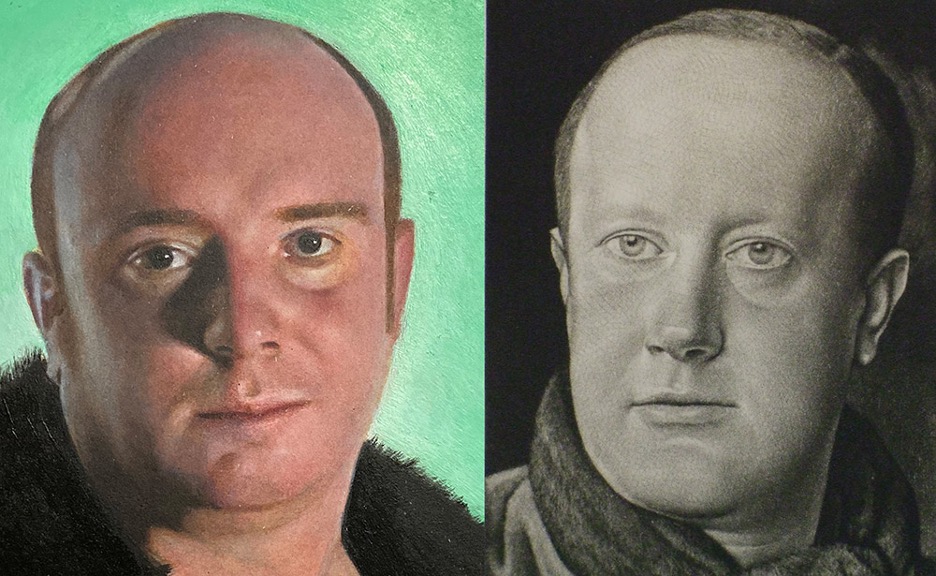

Showing concurrently with “The Intimacy of Others†is “Face Off: Patrick Smith with Victor Hammer†at the University of Kentucky Art Museum. The exhibition is comprised of Smith’s paintings and prints by Austrian artist Victor Hammer (1882-1967). Like Smith, Hammer’s images are of his friends. However, Hammer’s subjects (affluent individuals and diplomats, living in the complex and dangerous context of 1930s Europe) serve as a stark contrast to the subjects of Smith’s paintings: the working class, people of all genders, and people of all races.Â

A moment in “Face Off†features Smith’s 2018 Self Portrait in Fur next to Hammer’s 1926 Portrait of Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff. This moment showcases some of the cheekiness of UK Art Museum director Stuart Horodner and curator Janie Welker. The facial similarities between Smith and the subject of Hammer’s painting, Albrecht, are uncanny. This pairing of the two images is evocative of the feeling of time travel. And, in a way, so is Smith’s work. His attention to detail, color, light, and composition are reminiscent of the masters. The portraits are timeless; without the nods to contemporary life (the tattoos, piercings, and styling of his subjects) his work could very easily exist in another century.Â

The timelessness and the timeliness of Smith’s work are their strongest qualities. Smith’s paintings utilize the tools of the masters to question the very hierarchies that created mastery. His subjects exhibit agency, a self-directedness. They dare the viewer to not only look, but to see them as the fierce bitches they are. Most importantly they challenge subjectivity. Whose image should be painted? As Smith’s figures take on poses from classical paintings, they insert themselves into history – often in places where they would not be allowed.

References

- hooks, bell. 1992. Black looks: race and representation. Boston, MA: South End Press.

- Title Art:Â Patrick Smith, Christina, 2020, acrylic on Arches paper, 18.5 x 22.5 inches.