I met up with artist James Lyons at Bar Ona located on Church Street in downtown Lexington for our studio visit. This was the first place I’d met James and just one of the several bars where he works. It’s a gray and rainy Sunday evening. I knock on the front door and peer through the window into the dark bar. James sees me from behind the bar and lets me in. It’s an hour before opening. James is blaring music and the bar is filled with a distinct perfume. I ask him if he’s burning incense, “It’s sage†he replies; perhaps he is trying to fend off any bad omens in anticipation of my visit. Beers lie in crates on the floor waiting to replenish the coolers beneath the bar. The bar has been recently decorated for the holiday season, Christmas lights are strung above and adorn various plants. I start with a simple “How are you?†to which James replies “Tired.â€

When approaching James about a studio visit he insisted we meet at Bar Ona. “I don’t really have a studio right now,†James admitted. As a young working artist myself, I really related to this statement, and knowing James through bartending at an adjacent bar myself it felt only appropriate that we meet at Bar Ona.Â

In our text exchange prior to the visit, James had confessed to me that he was very nervous. “I can be pretty quiet about my art.â€

“Bring a shovel and DIG†he said.Â

So, with both of us exhausted from our weekend shifts, I began digging.Â

James is a Lexington native who hails from the Cardinal Valley neighborhood, a predominately black and Hispanic neighborhood tucked away near Red Mile. James describes himself as a “mean kid†and expressed to me struggles he had growing up with peers, the administration and most importantly his faith-based community. Growing up as a queer person of color within the Seventh-Day Adventist faith was not easy for James but would prove to be an incredibly formative experience, leading him to pursue art.

“It’s fucking crazy this bitch gets hit in the head in third grade, with a rock, she passes out…and then the next thing you know she writes 127 fucking very well written books about her visions…her real slapper was called the Great Controversy and there’s a passage that’s very, very close to September 11th.â€Â James was referring to one of the instrumental figures in Seventh Day Adventism, Ellen G. White, whose visions inspired her writings  – still held in high regard in the church to this day.

It was James’ upbringing as a Seventh-Day Adventist that would land him at Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Michigan. Andrews University, the first higher-learning institution founded by Seventh-Day Adventists, would provide struggles as well as opportunities for James. “It was so frustrating, here I am trying to find myself and there are all of these new rules. I had to sign a contract that basically signed my life away, I wasn’t even allowed to smoke.†However, Andrews also provided James with an underground network of young queer men, which allowed him freedoms he had yet been able to experience; more importantly, the university provided their photo department. Although James had been pursuing photography since high school, it was his time spent and the resources provided by Andrews that allowed him to hone his craft and provided him with the environment in which to develop his practice.Â

Following his graduation from Andrews University, James spent time in Chicago before returning to Lexington. Upon his return to Lexington James expressed to me both a frustration and passion. “I wanted to find the artistic community here and connect.†James began by publishing a photo portfolio, a book that was met with backlash and attempted censorship. “The company had a policy against printing nude pictures…there was this lady that worked there who was so helpful, I feel bad because she probably got fired for helping me print that book.â€

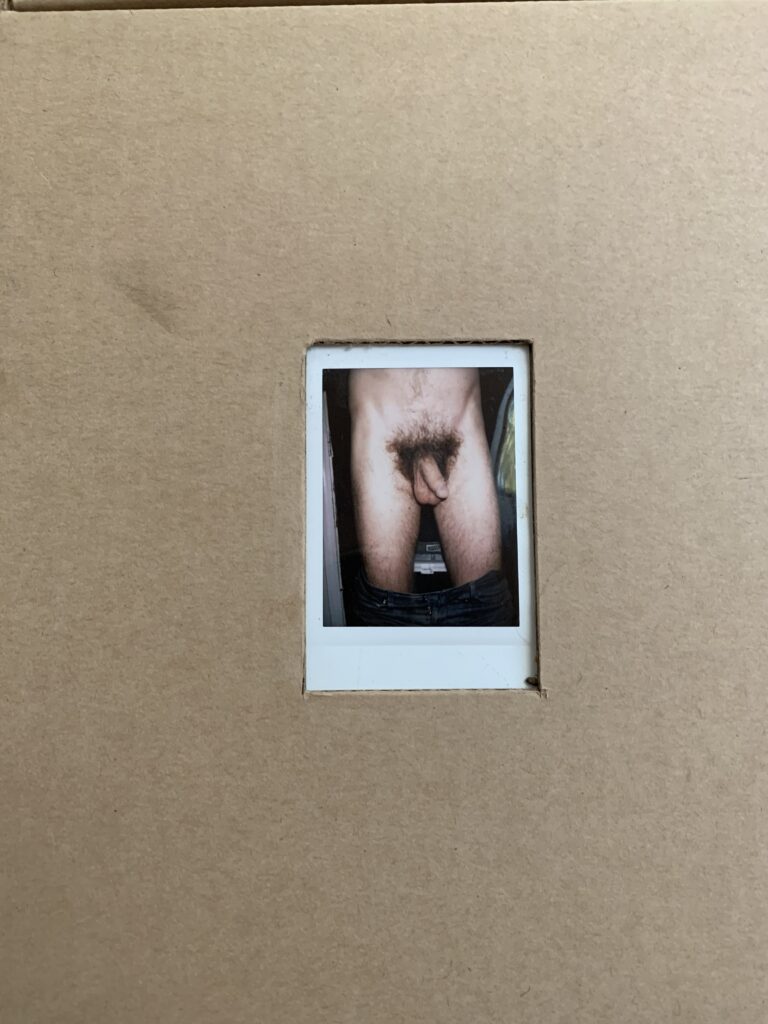

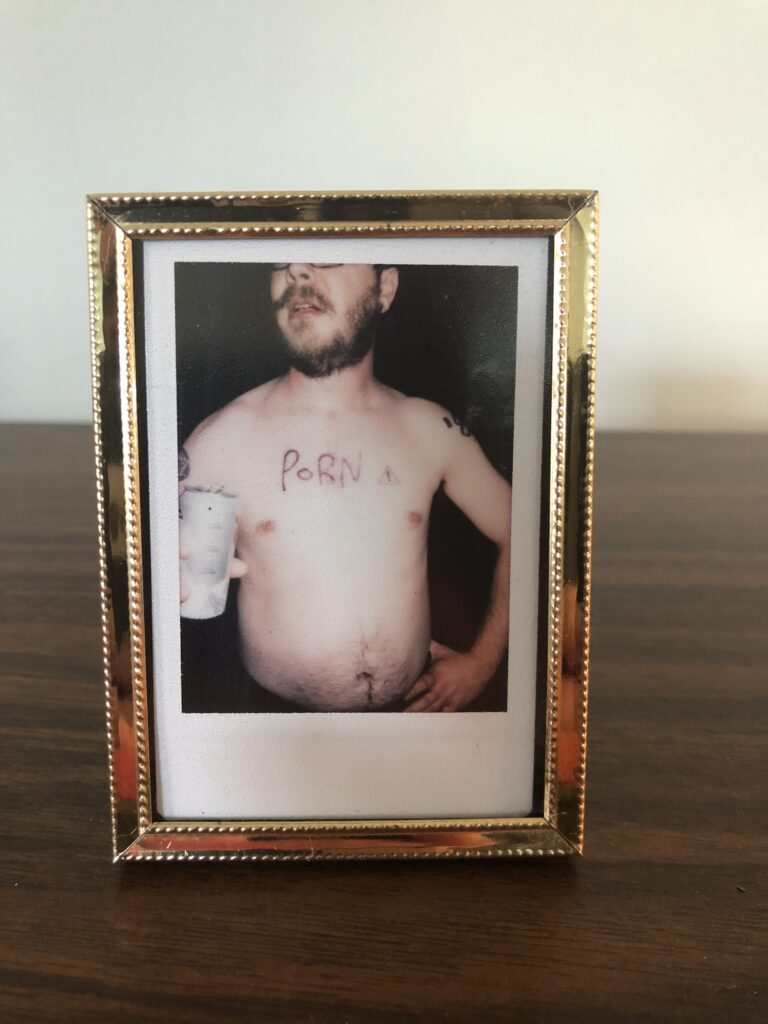

The complexities of societal relations with the nude image are nothing new to James or his work, and in fact are central to his best known body of work Frank. Frank, a show consisting of a collection of Instax photographs of flaccid penises, debuted at Parachute Factory in 2018. The show was met with equal parts praise and disdain. James once relayed to me a story about a group of teenage boys who came in and after spending a few moments with the show loudly proclaimed with disgust “Ugh, it’s just dicks.†When I got the offer to interview and write about James, I was most excited to discuss Frank with him.

On Frank, James had to say,

“I started reading the Male Nude in Contemporary Photography by Melody D. Davis on the same day I got my Instax mini in the mail, so I went downstairs to a house party and started taking pictures of people’s dicks.†James said.Â

Davis’ critique of the representation of the phallus in photo inspired James to produce this body of work.

“I wanted to create the antithesis of a big hard cock.â€

In our current political climate and the age of #metoo, Frank asks questions about consent, anonymity and celebration versus exploitation of the body. I was curious about James’ process and how he went about approaching the subjects of his photographs.Â

“I started the project as a way to learn to be a ‘good boy’ and meet new people.†James says when I asked him about his motivation for the project.

The subjects of James’ photographs came from all walks of life (bar patrons, friends, and lovers) and many were complete strangers. “It’s easy, guys are really proud of their dicks.â€

James attributes a bulk of the photographs to nights spent at Crossings, a local gay dive bar. Many of the photos were taken outside of the bar and in the bar’s restrooms. “The bouncer got mad at me and tried to kick me out but once they realized we were just taking pictures and not, like, doing coke, they left us alone.â€

Frank is both intimate and anonymous. The close cropped images draw the viewer in close only to provide them with very limited information about the subject beyond what lies within the 46x62mm frame. The series brings to mind Andy Warhol’s Polaroids, his glamorous subjects exposed and vulnerable, frozen for eternity within the frame and elevated to superstar status by Warhol’s hand. Lyon’s subjects are stripped of their identifying features but presented in a way which elevates them beyond just a phallus.

At this point in the interview the bar began to fill up, many passers by stopping to speak to James. James’ position as a bartender allots him a front row seat to the personal lives of so many, and through his career he has woven a web of subjects, muses, and companions who serve as constant encouragement, support and inspiration.Â

We step outside to have a cigarette.

“I love that you insisted on meeting at Ona,†I tell James.Â

“This IS my studio,†James replies.Â

“These people have taken care of me. They took me to Spain and paid for my trip. I ate at one of the top restaurants in the world and translated for one of the top chefs in the world.â€

I bring up the magic of bars, especially gay bars, to James. We discuss the openness and vulnerability that can exist within these spaces. “I always feel this presence when I am at certain gay bars, especially places like Crossings and Bar Ona that have alot of history. They feel alive or haunted in this really unique way.†I say to James.

James’ work provides us with a peephole into his world but more broadly the rich and varied queer culture within Lexington, Kentucky. We discuss how many young people are unaware of Lexington’s long gay past and its position as a gay mecca for the region. As we speak, artist Bob Morgan walks past; Bob dressed to the nines in his usual patterned attire stops to say hi and we talk briefly. James and I laugh about it, what are the odds of three gay artists all being in the same place at the same time in Lexington?Â

James is working to continue a legacy of queer art making in Lexington. Henry Faulkner, Stephen Varble, Edward Melcarth, Mike Goodlett, Bob Morgan and Louis Zoellar Bickett (a close friend of James’) and many more are joined in their efforts by James as he creates in his own way, documenting and preserving his experiences as a queer man of color in Lexington. James is paving a way for himself and others to follow if they choose to do so.

“I can’t even tell you how nervous I’ve been about this,†James confesses to me towards the end of the interview. I assure James he’s in good hands to which he replies “Alright, then I’m getting you a beer.â€

Â