Two recent exhibitions in Lexington, Kentucky operate as a collaborative undertaking that sheds light on an artist left to historical obscurity, yet one whose creative fervor and technical skill equate with his contemporaries. Edward Melcarth: Rough Trade at Institute 193 and Edward Melcarth: Points of View, on view at the University of Kentucky Art Museum through April 8, delve through the canon of American Modernism and uncover a lost gem: Edward Melcarth (1914-1973).

Melcarth left his hometown of Louisville in his youth for New York, where he would spend most of his adult life and made the majority of the paintings in the two exhibitions. And it shows—Melcarth’s canvases describe the nuanced intersections of maritime industry, physical labor, and leisure time experienced by the working class in many of America’s booming coastal hubs during the mid-1900s.

On view are an abundance of portraits and figurative scenes created during a historical moment when abstraction reigned as the premier American style. Yet a visitor who enters Institute 193 or the UK Art Museum is sure to detect traces of certain methods employed by abstract painters, especially in the expressiveness and vitality of Melcarth’s brushwork and handling of paint.

Indeed, Melcarth depicts his subjects with an apparent responsibility for the preservation of their individual identities. At Institute 193, a display of thirteen solo portraits indicates the nature and implications of Melcarth’s identity as a homosexual man living during an era when overt, often physical demonstrations of masculinity domineered nearly every social realm (recall Hans Namuth’s photographs of Jackson Pollock in his studio forcefully flinging paint onto canvas in 1950).

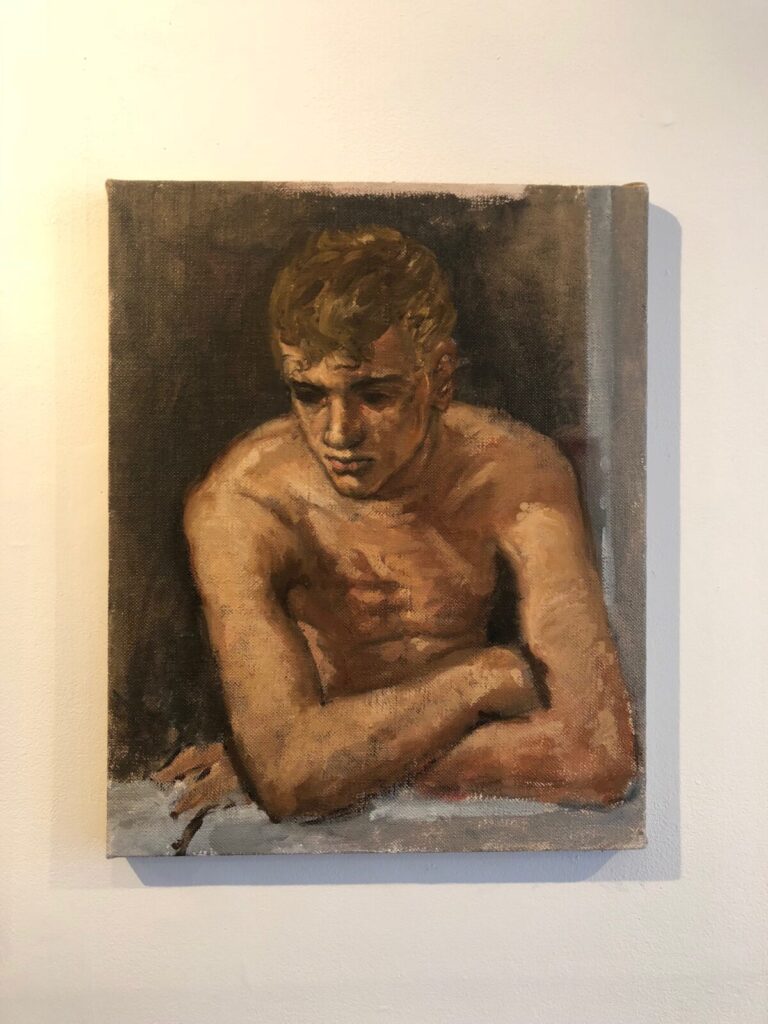

As for Melcarth’s paintings, rarely are the men looking directly at the viewer. In “Man Leaning on a Windowsillâ€, a shorthaired, shirtless man folds his arms as he diverts his stare downward out of a white frame. He is muscular and young, and Melcarth captures the light that hits his skin in a rich spectrum of warm tones. The man is literally and figuratively undressed, removed from labor and the outside world; here he is himself, and Melcarth is seemingly cognizant of the man’s identity as well as the potential for his painting to serve as reflection of the artist’s own sexuality.

Not all of the men featured in Rough Trade, however, are as evasive or exposed as the subject in “Man Leaning on a Windowsillâ€. The majority are clothed with their heads raised, and Melcarth utilizes numerous formal elements to evoke the social pressure he—and presumably the men he paints—endured to conceal their homosexuality from the public eye, not least of which is the application of stark lighting.

Light in Melcarth’s portraits frequently discloses, whereas shadows are vehicles for concealment. In addition, Melcarth at times positions the bodies of his figures away from the viewer, as if to represent the pressure he and the men he painted felt to shutter their identity from the public realm. The man in “Blond Youth with Brown Jacket†turns his head over his back towards the viewer, careful not to make eye contact. He whistles, denying conversation, and his reversed position implies his intention to move beyond the scene. Although his stature is unmoving in the painting, he signals uneasiness or perhaps surprise, seemingly taken unaware by the viewer’s presence.

At the UK Museum, themes shift from intimate portraiture to Melcarth’s life and vast capabilities as an artist. In Points of View, Melcarth’s breadth of expertise is showcased in paintings, sculptures, and drawings of still lifes, physical labor, bar scenes, and more. The array of artworks exemplify why, according to the exhibition’s statement, collectors during and after Melcarth’s life, such as Peggy Guggenheim and Steve Forbes, were drawn to his divergence from the periodic norm of abstraction. Melcarth’s ability to work in large-scale is arguably the focal point of Points of View; his monumental paintings marry classical themes and mid-twentieth century ways of life.

In “Excavationâ€, two men tend to a sea vessel’s floor. One man holds a large rope in his hands that is seen snaking over the boat’s edge in the background, while another man in a white sleeveless shirt rushes to his shipmate’s aid. The painting, like many other artworks in the exhibition, focuses on men engaging in a physically demanding activity, the contours and motion of their bodies exaggerated to the point of fascination. What’s more, what “Excavation†shares with it’s neighboring objects is a unique, inward looking viewing angle. Melcarth’s expert translation of this seafaring task is compelling in both its simplicity and accuracy, but “Excavation†is most intriguing as an indication of the artist’s capability to mold a remarkable composition.

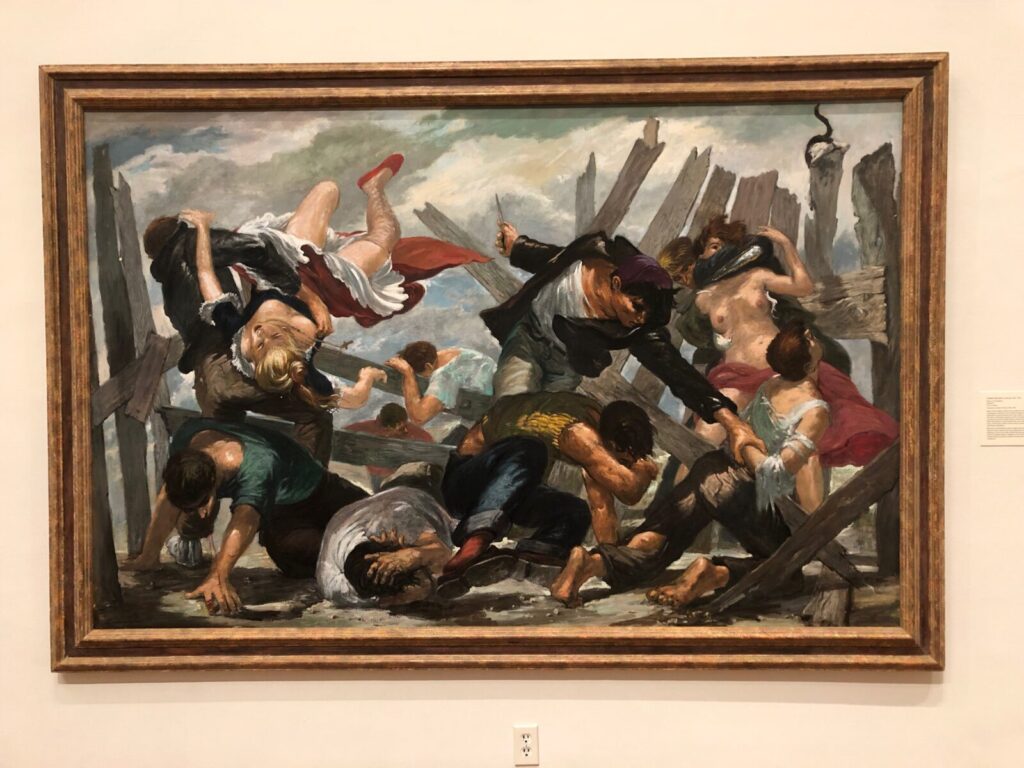

Melcarth pursues visceral movement as subject matter throughout Points of View, as evinced in works like “Rape of the Sabinesâ€. The title of the painting refers to a well-known Roman myth that carries motifs of abduction and calamity; artists throughout history, including Giambologna and Picasso, have employed the myth as inspiration for their art. The iteration on view at the UK Museum, which contains figures twisted amongst themselves rendered with anatomical accuracy, is a testament to Melcarth’s dedication to precision when illustrating the human form.

Where Melcarth breaks from other artists’ versions, however, is the portrayal of men—not only women—as victims of violence committed by other men. Possibly a subtle invocation of suppressed sexuality Melcarth and some of his subjects endured during their lives, “Rape of the Sabines†stands as a definitive expansion of timeless material.

But it is Melcarth’s “Last Supper†that draws considerable attention in the museum. Painted on a canvas that is elongated horizontally, Melcarth’s take on Jesus’s final meal before his crucifixion allows viewers to act as witnesses to a crowded bar of young, working-class men in bustling conversation, dodging other bar patrons, and attempting to hail the bartender. The countertop is scattered with bits of food and spilled mugs, and viewers are able to peer into the shelf below the bar’s surface accessible only to servers, which contains a range of food and dishes.

Historically, many artists make clear which disciple is Judas when describing the Last Supper, usually by turning him from the viewer or filling his hand with a sack of coins. In Melcarth’s scene, the man in the yellow shirt, with his left tricep flexed toward viewers, potentially fits this mold, but his role as bartender—the one serving others—arguably positions him as Jesus.

Melcarth, here, appears to imply that good and evil function not as a binary but as a spectrum in which the difference between the two is difficult to detect. An insight to his personal experiences, perhaps: Melcarth was an outspoken communist during his life whose sexual orientation and political views combined for reason enough for the FBI to keep a close eye on his activity, as noted by the exhibition statement at Institute 193.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s interpretation of the Last Supper is possibly the one that resonates most in public consciousness. In it, Jesus is situated at the center of the table, arms spread in an upside-down “V†formation. In the far right of Melcarth’s painting, a man in a red shirt mirrors Jesus’s position. Although he overlooks the scene, rather than frontally facing the viewer as Jesus does in Da Vinci’s work, his arms descend in the same arrangement. Were this hunched man in red Jesus, Melcarth’s scene would only simulate half of Da Vinci’s composition—viewers are only able to see the left half of the famed Renaissance fresco. Under this reading, Melcarth omits a crucial section of a dominant trope. His work is, inevitably, incomplete. Totality is withheld—a recurring theme as it pertains to the representation of identity in both Melcarth exhibitions.

The statement for Points of View calls the project a “homecoming of sorts, a chance to assess and appreciate†Melcarth’s work and career. Although the forces that have omitted Melcarth from the history of art are called into question with a critical eye, exhibitions at Institute 193 and the UK Museum function most pertinently as a joint celebration that posits Melcarth as an artist deserving of substantial recognition. As Rough Trade and Points of View indicate, Melcarth necessitated a conceptual break from popular forms of mid-century artmaking. These exhibitions are departure points for exploring why Melcarth diverted from abstraction, ultimately reexamining what we know about the trajectory of art.

Edward Melcarth: Points of View runs through April 8, 2018 at the University of Kentucky Art Museum. Edward Melcarth: Rough Trade showed at Institute 193 from January 13 – February 17, 2018. Both institutions are located in Lexington, KY.