“People love narratives. They love winning stories. They think it’s a love story, this Iraqi girl, this American man. But it’s not that easy or glamorous or romantic.” – Vian Sora

Prologue: End of Hostilities

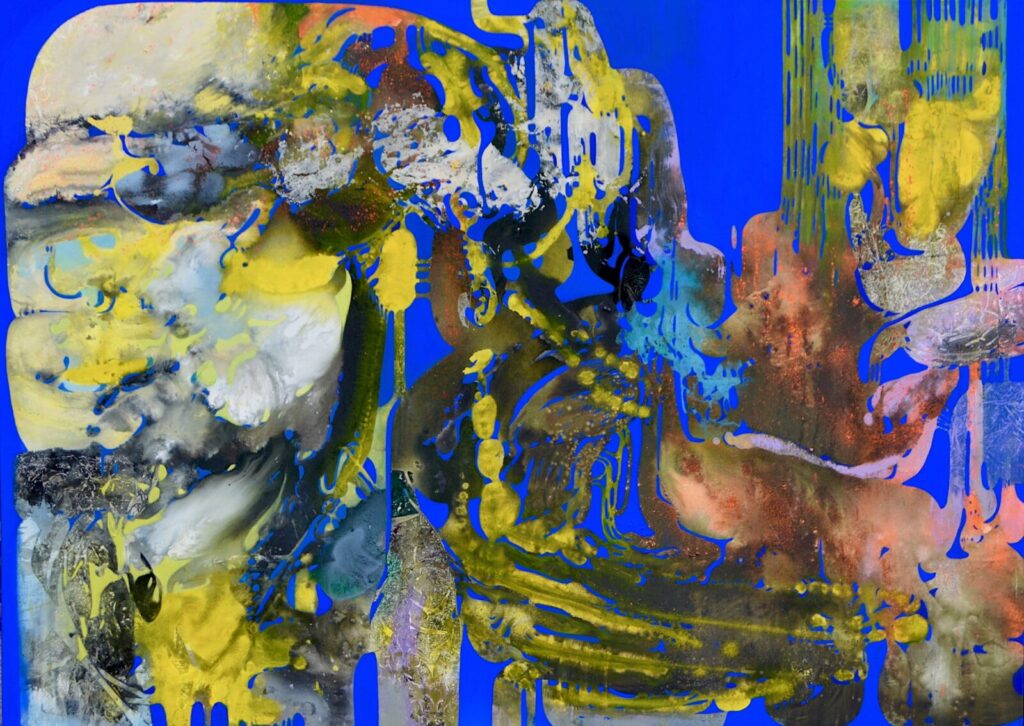

The first thing the eye sees is the tiny rivulets of blue, the happy hue of a robin’s egg or a bright morning sky, undulating dots and dashes that wind around the other pools of color: swathes of violet and lilac here, lakes of deepest green over there. Forms and shapes possess an organic fluidity, as if millions of tiny water molecules were swirling in frenzied motion within the mass of a large wave slowly rolling across the canvas.Â

There is a grittiness, too: dark bodies of black and grey, fragments of skulls and fractured bone hidden in the corner, half-buried under layers of pigment. Oxidized shades of crimson manifest like blood in all its violent expressions: splattered, bleeding and pooling. Even in the painting’s lighter areas, hundreds of hairline fissures materialize like the capillaries of human tissue or the cracked surface of desiccated land.

The work is undeniably chaotic, struggling to contain the exploded forms of color and texture and memory in a surge of energy and heat. And yet it also holds a persistent beauty, lines of elegance and grace that cut through the debris and roughness in lucid and reassuring curves. What is left is both a hope and a hollowness: streets clear of foreign tanks, skies absent of fighter jets, the silent stillness of a bombed-out city, this vast and sudden absence, this aching emptiness. Â

End of Hostilities was first shown in Sora’s solo show “Unbounded Domains†at Moremen Gallery in the spring of 2019 and then acquired by KMAC Museum through the support of a donor. It also served as the departure point for a new body of work Sora was creating for the museum’s premier Triennial (on view August 24 – December 1, 2019) when I visited her studio that July and August.

Sora’s work serves not only as a record of horrific acts of violence and the lives they destroy, but also as a way of making sense of war, of beginning to fill the void it leaves in its wake. In the aftermath of terror and destruction, she sorts through the smoldering rubble, searching for some small fragment of beauty that will tell her: All is not lost.Â

Part I: A New Language

When Sora came to the United States a decade ago, she brought with her a painting style and technique she first developed as a young artist in her native Iraq. She would begin by sculpting wet material onto her canvases, often in the intricate patterns of ancient Islamic ornament, and then build up multiple layers of paint in colors that offered the hazy illusion of sunlight seen through sandstorms. Only then would she add figures: translucent apparitions of veiled women, the primitive outlines of horses and birds. In the process of layering, Sora chose what to paint over and what to reveal, allowing her to hide forms in the canvas. “Most of my life in Iraq was very secretive,†she says. “I think most females are like that. And that technique was my little thing, my secret.â€Â

Sora had many paintings in this early style in her 2016 solo show at 1619 Flux, where KMAC curator Joey Yates first took notice of her work. “I recognized her skill and her aesthetic in that work,†Yates recalls, “but what I was really drawn to was a couple of newer abstract pieces that seemed unique to me. They had a very distinct visual language I hadn’t seen other people engage.â€

The paintings Yates saw were the first in a new approach Sora had been exploring in which she banished the figurative forms, abandoned the bas-relief foundation and traded the palette of khaki and desert and dust for a piercing intensity of blues and yellows and greens. Black made its appearance, too: sometimes as plumes of smoke drifting in front of the technicolor chaos, sometimes shooting across the canvas like gunpowder, other times lurking in the background as a subtle shadow presence. Abstract forms were unknowable as friend or foe: a broad palm leaf could reveal itself as a human lung upon second glance, the dripping tendrils of vines could morph into disembodied veins. Sora had stumbled upon a psychological trompe l’oeil, creating an uneasy tension between exultation and terror through this deft exploitation of form and color.

Two years before the show, Sora had undergone a major operation. She was given general anesthesia, organs were removed from her body, and when she recovered she began painting in a completely new way. “I woke up with a wholly different visual language,†she says. “I used different colors, I changed my technique. And that helped me make sense of my existence, using these colors that were foreign to me in a manner that doesn’t exist in real life, to create a world that somehow is in my head.â€

Sora has continued to work within this new aesthetic in the years following its introduction at the 1619 Flux exhibit, and she still has much to explore. “Even within this abstract language, she moves quickly,†Yates observes. “She’s not going back to the canvas with the same ideas. With the newer work, she’s making more vertical pieces and changing up the framing. She’s picking different colors. She’s thinking about different subjects. She’s able to maintain that identifiable abstract language as the same time she’s becoming really adept and nimble at working within it.â€

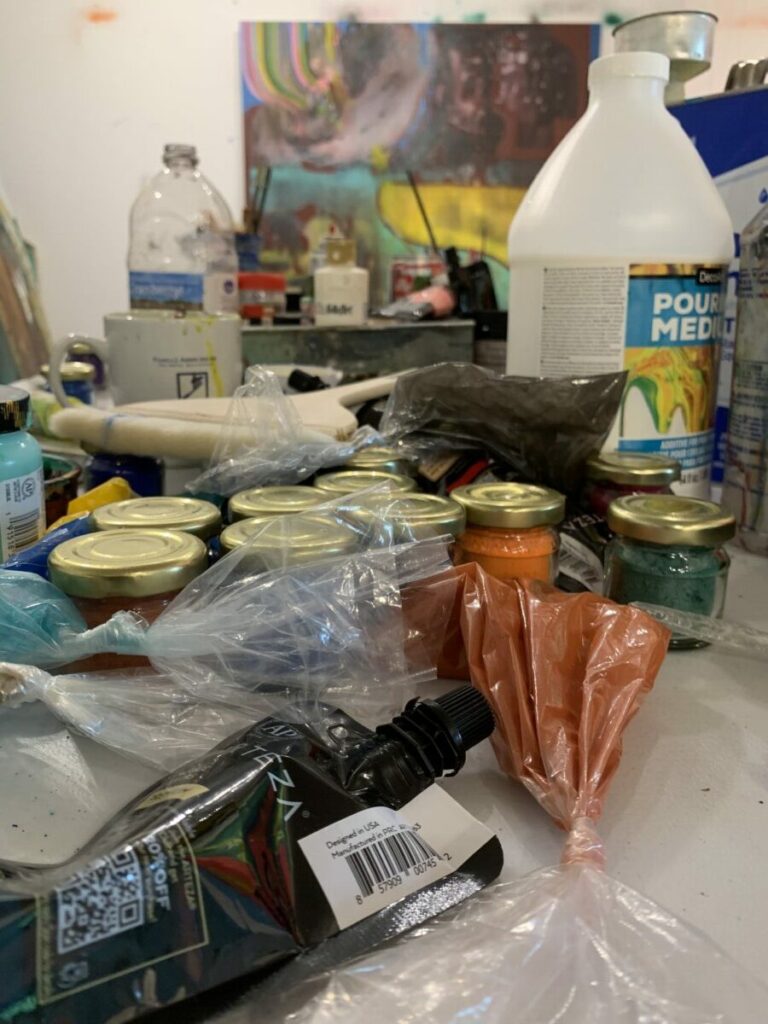

In Sora’s studio, the canvas starts down on the floor, subject to a blitzkrieg of fast-drying acrylics and pigments and inks, applied using whatever is within arm’s reach: brushes, sponges, paper, nylons, spray bottles. There is an earthly physicality to this work as Sora moves around the canvas, using arms and hands to manipulate the color, sometimes prostrating herself on the floor, face to canvas, using her breath to move the pigment in an extravagantly life-giving gesture.

“The beginning is very chaotic, the end is very controlling,†she says. “And the control is that tension between me and this thing called painting that is telling me, in some indirect language, that I need to go and work a little bit here to build those shapes. This is me finding the relationships and the bodies and the narrative that leads you through.â€Â

Even as Sora moves into the controlled part of the process, using a narrow brush of oil paint to carve out figures and forms, memory and meaning, one senses that she is still more midwife to the work than its master, not acting on the painting as much as she is allowing it to come into being. As she paints, her attempts to describe what’s happening between her and the canvas acquire a mystical, almost Tantric, vocabulary: she is doing what the painting is asking for, she says, following the lines to see where they take her, investigating forms that have the unsettling persistence of reoccurring dreams, led by some intuition she doesn’t always fully understand.

“I always start with an intention and an idea,†she says. “But the encounters that happen through the life of creating the work, you would not be honest to yourself and your path if you stick to the initial idea. You have to let everything that happens to you happen to the painting. It’s a long process. Some paintings take almost a year to finish because they have that much to give.â€

Yates readily observes these encounters in her work: “All the issues she may deal with – war and trauma and PTSD and violence and death – she finds order within that chaos. And that chaos changes, right? Sometimes it’s connected to her family, sometimes it’s connected to larger issues of trauma and migration, but those things always feed into her personal experience, and she’s translating them into that expressive abstract language.â€

“The bodies are still there,†he says. “She’s burying them in the landscapes.â€

Part II: Scenes From A New CountryÂ

“I love the duality of grotesque and beautiful. That’s what interests me,†Sora says. “The two things that have affected me most, visually, are amazing scenes of natural beauty – these landscapes that I’m obsessed with – and scenes from car bombs in Baghdad.â€

Ten years ago, when Sora began the process of gaining U.S. citizenship, she was restricted from leaving the country, cut off from the places that excited her – cities like Istanbul, Sao Paolo and Berlin that were teeming with the exotic vibrancy she found so invigorating. So she went to the desert – to Moab and Sedona with their colorful layers of rock, their mesas and bridges and buttes, those ancient vistas sculpted by air and water and the weight of time.

“The Canyonlands are very intense,†Sora says. “That visual landscape, that kind of terrifying beauty, completely messed me up. It’s like a scene from an archaic war zone, like the scene of an explosion. The way the light creates illusions on all these layers of rock. It feels like you could fall and break into hundreds of pieces. That sense of emptiness makes me want to go fill it with something.â€

At the time, Sora and her husband were living in an elegant apartment overlooking a century-old park in Louisville, Kentucky. But because they were renters, she was afraid to attempt anything that might mar this borrowed home. She felt constricted: “I don’t like what I painted there because for me to work in a space it can’t be white and clean and perfect. I have to destroy the place to feel free enough that I can paint.â€

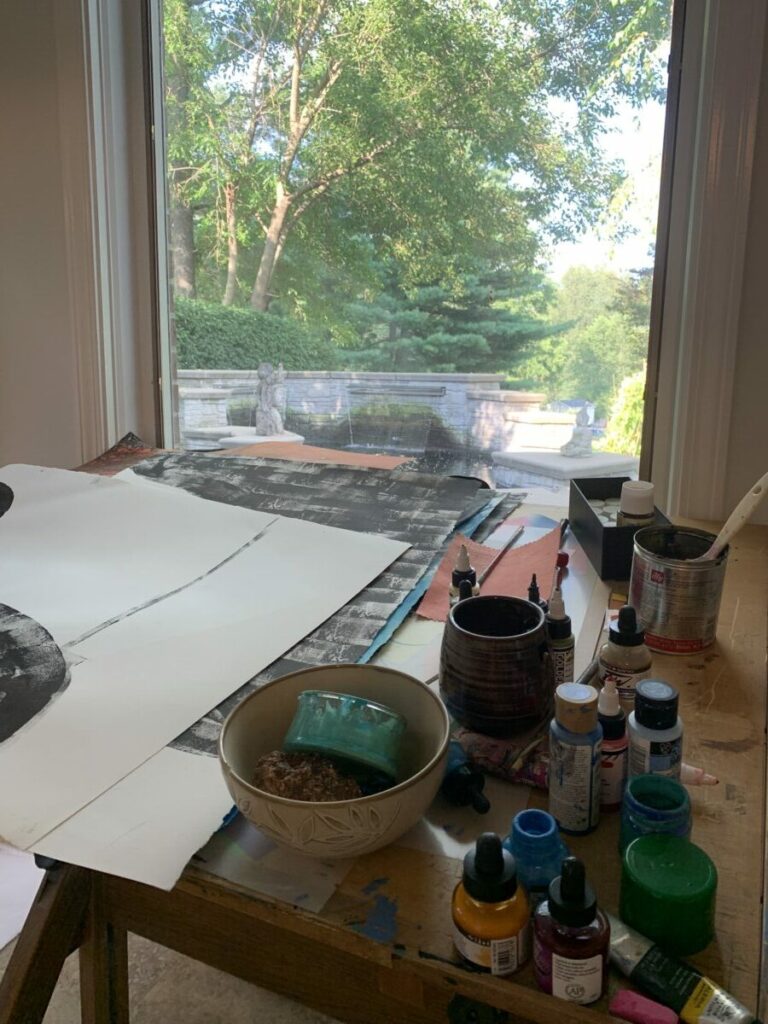

Three years later, Sora was granted a citizenship that made her both subject to U.S. laws and free to leave its borders. She and her husband bought a house on a quiet suburban street, where Sora now has a light-filled studio with windows that look out onto a verdant garden with a small koi pond that her cat, Lilu, watches intently. Inside, linoleum tiles catch paint in splatters, drips and spills; a wooden drafting table gazes upward to the windows; a battered, armless office chair slumps abandoned in the middle of the room. Drawings and sketches scatter the floor, torn fragments from older sketchbooks pile up comfortably on the sofa as Sora apologizes for a mess that doesn’t actually exist.

“It’s kind of embarrassing, but I cannot work in an organized environment,†she tells me. “I once tried to force my space to look like one of those perfect Vogue magazine studios. I got color-coded drawers and organized everything, separated the acrylics, the pigments, the oils, the oil sticks, the whole thing. And then without even realizing what I was doing, within a day everything was mixed, everything was destroyed. But I think it’s part of the process. The chaotic start and then the control.â€Â

Sora is in her studio sixteen hours a day if her schedule allows, often working well into the night, sometimes waking from a dream and descending to the studio to feed it to the canvas. In many ways, she is doing the work of every artist, translating personal experience into a unique visual expression, putting memory into form and turning feeling into color. But Sora works in an emotional alchemy as well, taking what is secret and dark and buried, all that is grotesque and awful and horrific, and transmuting it into something light-filled, as beautifully ordered and knowable and free as the natural universe.

“I’m trying to make sense of these visuals that are coming out indirectly,†she tells me. “Most of this recent work, I feel, is an internal landscape. An internal landscape of a woman who lived through wars and physical discomfort, who was in accidents and witnessed family members die. And these grotesque, awful situations, I can turn them into something meaningful and powerful.â€

Sora wants her paintings to start a conversation about the effect of displacement and migration, about the effect of war on the human soul. And while this may cast her as a political artist in some minds, the great accomplishment of Sora’s work is, in fact, that it transcends the political. In choosing to find the beautiful in the grotesque, the order in the chaos, the tiny buds of green amid the rubble of destruction, Sora is affirming a world of pleasure and delight and spirit and wonder – those very things that remind us of what it is to be human.Â

We are, in Sora’s words, “all of us, starving for connection with something. With each other.†And in her search to recapture what she’s lost – the smells of her grandmother’s garden, the warmth of her childhood summers, the textures of her homeland – Sora is able to find that universal human desire for love and belonging and connection, carving out a space that’s free from the political and full of those personal, intimate encounters that make a life rich with meaning.

“There is a certain smell and a temperature associated with my childhood and I’m always trying to replicate that,†she says. “It left such a gap in my soul not to have that anymore when I left Iraq. Maybe that’s why I use all these warm colors. For me, the scariest thing is not to have memories.â€

Part III: Ancient History

Vian grew up in Baghdad, in a house where artists were always coming and going. She spent a lot of time in her grandmother’s garden, playing amongst rose bushes and pomegranate trees. In the summers, her family went to museums and archaeological sites along the Mediterranean. She loved art and math because they were the only things that made sense to her. She made drawings every day.

Then there was a war. The students had to go back to school even though there was no gas or electricity and smoke everywhere. One day, Vian was walking to school and a member of the Iraqi Intelligence Service ran a red light and hit her with his car. She flew six meters into the air and landed on her leg. It shattered. She had seven surgeries and walked on crutches for three years. Every day, she painted and drew.

She began showing her art in local galleries. Then she studied computer science and took a job with Mercedes-Benz. She was very good at it and all her colleagues loved her. Vian hated it and quit within a year so she could be an artist. Her boss with the very thick German accent said, Come with me. It was late and everyone else had gone home. She followed him back to his office where he opened a closet door and gestured inside. My wife, Maria, she was so miserable here in Baghdad. She thought she would take painting classes. All these expensive supplies. You should have them. Go be an artist.

Vian had her first solo show in Baghdad when she was 24. Her friends from Mercedes-Benz came and bought all her paintings. Foreign workers came to the galleries each day after they finished looking for weapons of mass destruction. Then her uncle was killed. Her father disappeared. The Iraqi government told the family he had been killed. Then he showed up one day. He had been tortured and imprisoned. The whole time this was going on, Vian painted and drew every day.

She took a job at the AP. She started as an assistant, but quickly learned all the jobs because her co-workers kept getting killed. Mostly she reported on car bombs. She and her crew would go to the bomb scene and interview people at the sidewalk cafe that now had bodies and body parts and organs everywhere. Vian would go back to the office and edit the footage and file the report saying how many people had died. She did this for three years. At night she would go to her studio and paint.

Then one day she and her colleagues were returning from a bomb site and they were bombed. Half the people in her crew died. The AP flew her to London and gave her a job and treated her like a hero. It was springtime and the city was sunny and beautiful. Vian wanted to kill herself. She met an American man who collected her art. She said, Look, I am really not the person you want to be with in a relationship with right now. But she was very smart and very beautiful so he ignored her. They lived in Turkey and the United Arab Emirates and then they moved to the United States. Vian had shows in Ankara and Istanbul and Kuwait City and Dubai.

She painted every day.

Epilogue: Last Sound

Late July, high summer. Uncomfortably humid, the sun intensely bright. The birds are silent, the trees are motionless in the breezeless air. Animals hide in shaded corners. Inside the artist’s studio, it is cool and quiet. The cat sits on the floor and watches the koi fish; the writer sits on the sofa and watches a painting that’s in the process of becoming Last Sound. The artist stands before a canvas taller and larger than herself, looking for meaning. Her dark hair is swept into a gracefully messy bun, her smooth olive skin smudged with pigment. She holds a broken piece of porcelain – it was the closest palette within reach – with a vivid blue oil paint and murmurs to herself, or perhaps to the canvas, as she contemplates the forms taking shape.Â

It’s a conversation she’s been having, in some way, every day since she was a child and first put line to paper, that primal impulse to find meaning and give it expression. In a world where wars can be started by men in underground chambers, where a judge can decide the fate of an asylum-seeker, where entire lives can be blown apart in an instant by a 19-year-old boy with a suicide wish, art – the act of creating – offers its refuge of order and elegance, its unknowable grace. “How important is beauty to you?†the writer asks, and the artist holds her gaze on the canvas as she responds:

“It’s everything.â€

UnderMain would like to thank The Great Meadows Foundation for support of our 2019 programming, which will include twelve in-depth studio visits of Kentucky artists. See our other publications related to this project:Â

Emily Elizabeth Goodman visits Melissa Vandenberg

Hunter Kissel visits Harry Sanchez, Jr.Â

Jim Fields visits Skylar Smith

Keith Banner visits Michael Goodlett

Miriam Keinle visits Lori Larusso

Sso-Rha Kang Visits Carlos Gamez De Francisco

The Great Meadows Foundation is a grant giving foundation whose mission is to critically strengthen and support visual art in Kentucky by empowering our community’s artists and other visual arts professionals to research, connect, and participate more actively in the broader contemporary art world.