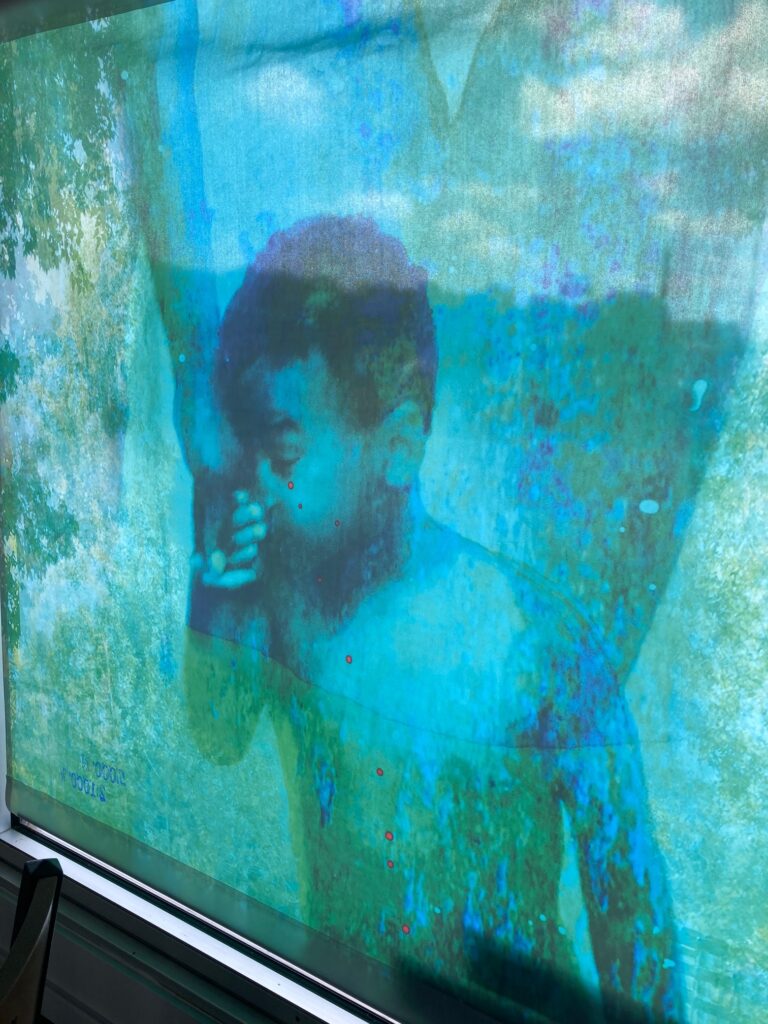

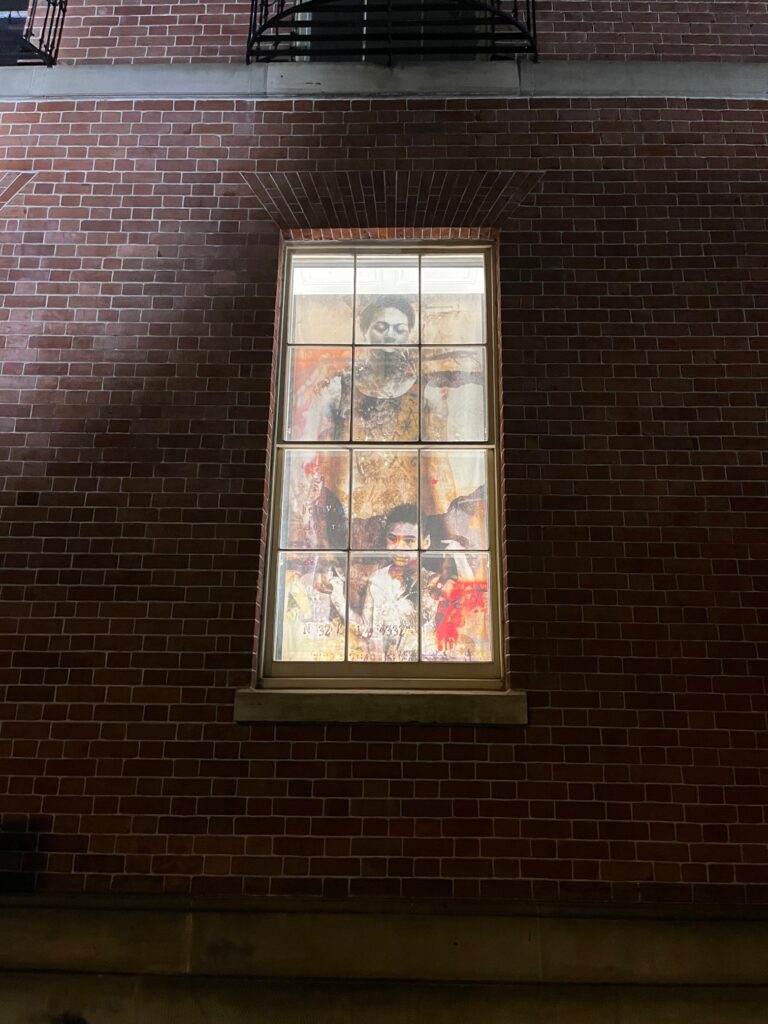

I Was Here is a project that hopes to mend the brokenness in our understanding of what citizenship is. As a Black journalist, I was drawn to I Was Here because of its exhilarating telling of enslaved people’s stories. The project consists of a series of photographs printed onto translucent tapestries. The images are of both individual and groups of Black men, women, and children, often embracing. The tapestries are often placed in windows, the light from the building shining through the translucent fabric, giving the figures a spectral quality. The figures stand and face outwards, some look down or to the side, but most look forward. As if imploring passers-by to look back at them.

These ethereal figures represent ancestral spirits, the mothers, fathers, sisters, and brothers who are often erased from history. By way of this project, they’ve appeared in the Octagon Museum in Washington D.C., the Lexington Legends ballpark, the Dyckman Farmhouse Museum near New York City, and the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville.

I Was Here has received awards and grants from a variety of organizations including the Trust for Historic Preservation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the American Association for State and Local Histories, Codeworks, and the Kentucky Arts Council Bluegrass. I recently met with Marjorie Guyon and Marshall Fields over Zoom to discuss the project.

Marjorie Guyon, the artist responsible for the project’s inception, read from a program describing the project, “Ancestor spirit portraits have been integrated into key historic sites across the country. Through these installations, the iconic spirit portraits create a visual for an invisible history. They ask us to examine who we are to each other, who we are as a nation, and how we can work to heal the wound in our citizenship created by enslavement.â€

The catalyst for the project began on a night full of contention for many Americans, the 2016 election. Marjorie shared, “It was the night that Trump was elected, and I was on the phone with my daughter, who was at that time clerking for a…judge in Nashville. And she was like, Oh, my God, I can’t believe this is happening.â€

The next day a woman came to Marjorie’s studio and said something very similar. It was Ashley Grigsby, someone Marjorie had met at The Nest, a social services organization in Lexington. Ashley is a member of The Nest board and was introduced by Marjorie’s friend Jeffrey White, the center’s executive director. Marjorie explained:

“[The idea for the project arose because ] I was doing a project for The Nest and [Ashley] was supposed to come, it was like November 9, and interview me…and so she came up to the studio, and she’s like, ‘I can’t’. And I’m like, what’s wrong? And she [echoed] what my daughter said: This country is not safe for me. And I said to her, basically, what I said to my daughter, and that was, we’re going to find a way to shift the spirit of the country. And she said, How are we going to do that? And I said, ‘I actually don’t know. But we will find a way.’ That both daughters of America said…the same thing to me within the space of twelve hours was significant.â€

Marjorie believes in art’s power to change the energy in a space.

“What a painting does is it shifts the spirit in a room. So you can put the right painting in the wrong room, and it won’t work at all. And you can put the right painting in the right room. And it totally fills the room with joy. It blesses the room, it enlightens the room.â€

Guyon’s belief in the “muscular power of art†and its ability to uplift the community may have been influenced by her growing up in New York, an extremely visual city. She describes a foundational experience that took place at the Museum of Modern Art, witnessing a 30-foot collage called Patchwork Quilt, made by eclectic expressionist Romare Bearden in 1970. The collage depicts a jet-black woman with an Egyptian profile lying across a patchwork quilt.

“I looked at it and there was absolutely no reason in the world for me to see myself in that construction. But I did. And that feeling of having something inanimate speak to me; being able to really listen to art is something that’s been a part of me ever since I was really little.

You grew up in New York, you’re constantly looking out your window into other people’s apartments. I looked out the window, and I had a vision of an African mother and child that moved, like points of light from window to window.â€

Marjorie mentions that her studio is situated directly across the street from an area called Cheapside, which was the largest auction block for enslaved people west of the Allegheny Mountains. Thousands of people were auctioned here, at one time the center of the slave trade. Auctions often led to the separation of the families that were sold. These were great sources of trauma and created a historic wound on that site. In July 2020 Cheapside was renamed Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park, after a formerly enslaved man who later became a successful building contractor and entrepreneur in the Kentucky area. In response to the name change, Take Back Cheapside co-founder DeBraun Thomas said, “We know that the renaming of the space will not change the atrocities that happened in Cheapside or make it an inclusive place. It is, however, a much-needed step for the true healing and reconciliation that our community needs.â€

Marjorie conferred with her colleague Nikky Finney, a founding member of the Affrilachian Poets and an American Book Award winner. “I showed [my vision] to her and she said, it shouldn’t only be a mother and child, it should be the entire family. And so I reached out to Patrick Mitchell.â€

Patrick J. Mitchell is a Lexington-based photographer who has shot for the NAACP, The People’s Campaign, and The Bluegrass Community Foundation. He has been published in The Anthology of Appalachian Poets.

“I told him what I thought we needed to make a portrait of family: a powerful, beautiful, dignified, and holy people. And he said, “Okay, what do you want them to look like? And I said I don’t know. I’ll know when I see them. So we went to Walmart, and we looked at people. And then we had an audition in the studio. We picked a group of nine people, two of which were Ashley and Carson, the mom and the little boy that had begun it.â€

One of the project’s foundational qualities is its accessibility to the public. Because the tapestries are placed in the windows of churches, storefronts, bars, and other common buildings, there is no cost to access them. The images of these ancestral spirits are as present as the wound left by slavery in this country. Their accessibility makes it so that the public may walk by these images every day – and perhaps gradually change the viewer’s relationship with that space. Guyon has often experienced the educational influence that her art has, including the time she was giving a tour of tapestries installed in the buildings surrounding the Lexington Courthouse. The tour group was made up of middle school children in a downtown Montessori school. Marjorie shared:

“Before we started, [I asked] Does anybody know what happened here? And this little girl said, Well, slaves were sold here. And I said, No, actually, people were sold here. She had never thought about it that way. We have all these ways that language works to tell a certain story. But the fact is that power is the one who writes the history. So whoever won the fight gets to say how it happened.

“So what we’ve done in downtown is we’ve offered the augmented reality, we’ve integrated pages from books of elections, Lexington history, that have ancestor spirit portraits in the story, but in those actual books, the enslaved are nowhere to be found, although they’re actually the foundational members of the community.â€

Another time was in Washington D.C. when the I Was Here team was asked to speak at a virtual panel for the Octagon Museum. The Octagon is the headquarters of the Architects Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the American Institute of Architects. While preparing for the webinar, Marjorie did some research and found that white men like plantation owner and businessman John Tayloe and physician William Thornton were often credited with building the Octagon. In truth, the Octagon was built by enslaved people.

“But now there are seven larger-than-life ancestor spirit portraits that are permanently installed into the Octagon Museum, two blocks away from the Capitol. What does this do? This changes the narrative of the Octagon Museum because they no longer say that the Octagon was built by John Tayloe.â€

Both moments speak to the influence that the portraits have on the viewer, but they also have a great influence on the participants.

Marshall Fields, who was introduced to the project through Patrick Mitchell, auditioned to be a model and later became one of the principal members of the project. Marshall’s mother and daughter are also featured in the portraits. Fields is the project’s community liaison. He also wrote the prayer used during the memorials meant to pay respect to the people that faced horrible atrocities at certain historical sites. The sanctification ceremonies are carried out by members of the project along with community members. Opera singers from the University of Kentucky come to gather and sing, to acknowledge the pivotal role that enslaved people played in the creation and maintenance of this country.

During the interview, Fields describes the importance of I Was Here to the Black models who took part.

“I have a friend who is Scottish. I was at his home…and he was showing me his coat of arms, and showing me all of these different patterns, like Argyle patterns. And he went back about 500 years. I can’t go past two generations, you know, I’ve got my mother’s mother, and then my mother’s mother’s mother, you know, so my great-grandmother. That’s it. That’s all I have. And so the ancestors, spirit portraits, they create archetypal ancestors that can serve as an example, and serve as an image.â€

This is the first time that I Was Here’s potential was described to me from such a perspective. I, like Fields, cannot look very far back at my ancestry. I have no artifacts except for photos and those photos are of family no older than my grandparents. I am often shocked that some of my friends of European descent can look back hundreds of years and am saddened that I cannot do the same. I spoke of this idea, the lack of tangible history, with Fields and Guyon. Fields responded, “In the absence of documented fact, or stories that have been known and been able to be passed on, you can only use your imagination and your desire for what that must have been like.â€

These vibrant tapestries can serve as artifacts through which we may imagine our ancestors just as they must have imagined us. The decision to use living persons (instead of old photographs) greatly enhances the timewarp experience of the project. It seizes and personalizes your interaction with each portrait.

We discussed the fact that even though it is valuable to have tangible items to pass down there are also intangible things that are passed down, even when family units are separated. Senses of humor, taste in food, traumas and fears.

“The people who haven’t experienced what you and I have experienced, they also have had things that are passed down, and they have more tangible evidence of it. …Statistically, someone’s related to Klansmen, someone has had grandparents or great-grandparents who have lynched and been a part of these negative things. And that does not define them. But it does give them the opportunity to receive that thought process and indoctrinate it and make it their own, no matter how subtle it might be in today’s day.â€

This comment was profound to me because it highlights the privilege of knowing one’s own history and how it allows one to identify toxicity within oneself or community and to either embrace that toxicity or to reject it. Because of their visibility the ancestor spirits make it hard to ignore the wound that enslavement has wrought in all of us. But, it also provides an opportunity for us to empathize with ourselves as well as with others.

The portraits are not only of the ancestral spirits but also the models that represent them.

This coupled with a comment Ashley Grigsby made to Fields highlights the project’s ability to not only honor the past but to acknowledge the present. “When I had that vision of the African mother and child, I told [Ashley] and she said, “That’s amazing. Because as a Black woman, I’m always invisible.†And so what’s been funny is that now she’s everywhere. Her and her little boy. There’s this restaurant here, downtown. [Ashley] went there, and the owner went “Ashley, oh my God, it’s so good to see you.†She called me and she went, “That lady knew me… People see me.†She’s in D.C. She’s in New York. She’s in Louisville.â€

To know Ashley, her son, and the other families depicted in the portraits, to see her everywhere, is to see her ancestors everywhere. Possibly even more powerful is seeing these images as ancestral spirits. To see the ethereal bodies of people long past and look into their eyes and acknowledge their existence is to acknowledge the present existence and experiences of the present-day Black individual. It creates the opportunity to not only remember and mourn but to also effect change in the present. To heal the wound. You don’t remember a wound, you need to heal a wound and that is what this project asks the viewer to do. You tend to it every day until it heals. Remembrance is the tending. Acknowledgment is the healing.

Guyon summarizes this well: “A piece will become a touchstone for, say, a kid’s school bus route home. And if he sees this mother and child every single day, it begins to take root in him. It starts to serve the function of a memorial and a guardian.â€

To learn where the I Was Here project is installed and upcoming destinations, visit i-was-here.org.

Top image: Installation for the “I Was Here” project, courtesy of Marjorie Guyon. Two black and white photos of parents with their children can be seen through two windows.

UnderMain: On the Road sends writers out of Kentucky to explore the visual arts in cities of the Midwest and near South. This program is generously supported by the Great Meadows Foundation.