In January 2020, writer/curator Miranda Lash visited Louisville-based artist and gallerist John Brooks for the UnderMain Studio Visit series. Her piece detailed a bit about the artist’s background and explored his series A Map of Scents (2018-19). Following Brooks’ second solo show at Moremen Gallery and national coverage of that exhibition in The New Yorker magazine this year, UnderMain returned to his studio to talk about what has changed for the artist since our last visit. Portions of the conversation have been edited for length and clarity.

Throughout the first year of the pandemic and into 2021, John Brooks labored in his studio developing the body of work that would eventually become his most recent solo show, We All Come and Go Unknown (Moremen Gallery, Louisville, Ky, 2021). In the process of conceptualizing and creating paintings for that exhibition, a particular piece began to stand out from the group:

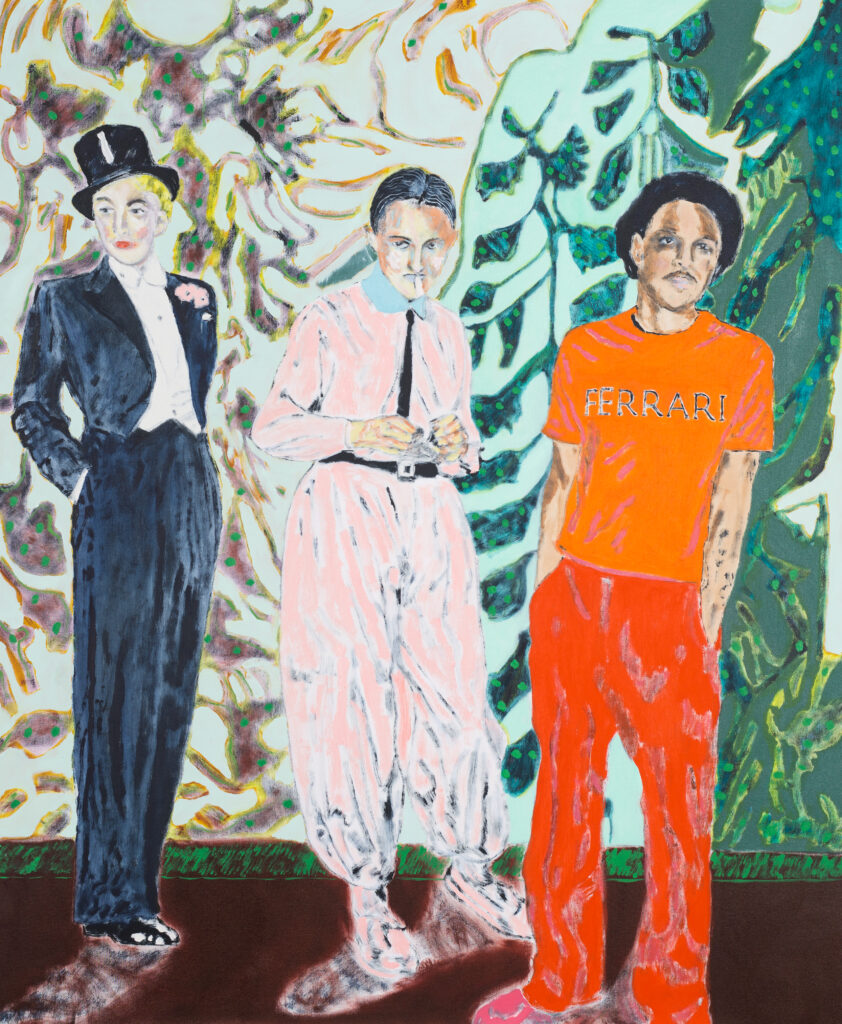

“The one painting that sort of shone the brightest was the painting with Nick Jonas and the two poodles and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff in the background,” Brooks remembers. “I realized the reason that painting worked was because it felt very specific to me, that only I would put Nick Jonas and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and poodles together. I realized that I have so many interests and so much useless, or useful – depending on how you look at it – knowledge and inspiration and stuff to work with that I’ve been carrying around for years, and I think in the past I’ve been reluctant to fully dive into that. Through the creation of that painting, I realized that’s exactly what I need to do. It is the very specific, particular makeup of my interests that, when applied to my practice, result in work that is more compelling and more distinct.”

Brooks goes on to discuss how the inclination to make work that appeals to a wider audience necessarily dilutes the message and intention of the work, creating art that is, ironically, less accessible. Instead, he advocates for honing in on individual interests and experiences as the path to making work that is both honest and compelling. He confirms, “I’m making work that I want to make. I feel a great sense of freedom in that respect. I feel, all of a sudden, rather unafraid, which I think is necessary. I’m not interested in making impenetrable work…I think there are a number of entry points for people.”

Brooks lists the human figure, palette choices, and art historical aspects within his paintings as different points of entry for different people. While his recent works may reference the past through art historical allusions, these paintings are firmly situated in the present. In a way, they are made of and for the Internet Age, where time and space are flattened, and the ephemeral takes on an aspect of persistence. Brooks operates in a post-internet context, engaging and exchanging with Millennial models and maintaining a presence on social media, all while outputting in the traditional media of oil paintings. How does the artist reconcile inhabiting both analog and digital realms within his practice?

“I sort of make no judgments about where I’m pulling things from,” Brooks declares. “I don’t feel any limitations. If I want to pull something from [Sandro] Botticelli, or [Diego] Velázquez, or [Max] Beckmann, I feel quite free to do that. If I want to pull from Nick Jonas, I also feel free to do that, because the connection is the human experience, and relationship to creativity, and I think I’m finally at a point where I don’t feel like I have to put parameters on what I’m looking at or where I’m pulling from.

“It is true that a lot of my models – not all of them but a lot of them – are quite a bit younger than me. And that’s really a result of the internet, and a result of Instagram. I grew up at a time and in a place where I didn’t know anyone who was gay. It was something – a part of me – that was to be hidden, something I was very shameful about, and at forty-three [years old] I’m still working through that. I have to give so much credit to the forum of Instagram, because it has allowed me to build a community that spans the globe. And the interesting thing about making connections that way, especially with other queer artists and queer people, is that there are ways in which our experiences, when shared, sort of connect and make sense to each other, and I want to celebrate that.”

In interviews and writings, Brooks has alluded to the notion that those who refuse to acknowledge the past are doomed to repeat it. Much of this concern is explained through his interest in German Expressionism, and the familial connection of his grandfather serving in WWII. Additionally, the artist maintains an engagement with the political, both generally and personally. Brooks states:

“I think especially now, in the United States, there are some really frightening corollaries to things that happened in the early 1930s in Berlin [Germany]. And how can we be in this place again? It all comes back to fear of the other. That’s part of why I’m sort of shining a light on my queerness and the queerness of my wider global community and historical community, because we’ve always been here and we’re not going away. I’m okay with making people a little uncomfortable in order to get them to look at things maybe they wouldn’t look at otherwise.”

That discomfort is where growth comes from. To make safe work or work that appeals broadly is to do a disservice to your audience, a placating move more than an implicating or engaging one. It is often said that audiences complete artworks, so to create and hold space for ideas to function and flourish within society is a necessary goal for an artist like Brooks, who is concerned with aspects of identity, emotional resonance, and politicization. In his piece “A Kentucky Painter’s Travels in Queer Time” for The New Yorker, Garth Greenwell describes Brooks’ recent work as mining the past and envisioning the future to infuse the present with notions of queer utopian ideals. This wasn’t an intention the artist explicitly set out to resolve, though the speculative does play a pivotal function within the work. Brooks explains:

“I think it happened organically. There were elements of these different things that had been present in my work, but they’d never been quite integrated in the way that I did in the last year. I don’t think I necessarily have any answers. I don’t think that the works are a how-to guide about how to move into the future, other than to say that there are people and experiences and certainly artworks that exist in the past which, if we’re paying attention, we can use to make things better in the future.”

A striking element in Brooks’ paintings is the quietly celebratory nature of the content, but also the de facto kind of approach to depicting the way everyday life can function. Here, the artist alludes to potentials: a world that is simultaneously just out of reach but has already arrived. The artist expands on this thought:

“In a general sense, we’re not there. But in a day-to-day sense, depending on the day or depending on who you’re with, or where you live, or where your circle is, it’s very much here. I think that’s part of where that celebratory feeling came from, because I do feel a connection with these people – some of whom I’ve met in person but many of whom I haven’t, both my contemporaries but also figures like Marlene Dietrich. So there are many realities in a way, [the paintings] were presenting something that doesn’t exist and in many ways can’t exist, but also very much does exist. It’s not one-hundred-percent one or the other.”

This liminal space helps to imbue the works with that kind of vibration that keeps a viewer coming back into them. If they were immediately readable, we’d push right past them. “I think if you understand a painting, or you think you understand a painting, you stop looking at it. It doesn’t work,” Brooks affirms.

One of the reasons why celebratory artworks by queer artists and artists of color are excluded from exhibition spaces and academic conversations is because the white heteronormative mainstream refuses to relinquish control and create space for conversations initiated outside of the mainstream. This necessitates folding speculative and utopian ideas into the present, subverting the power of an established system by asserting that an alternate realization of popular culture is already in existence. Brooks’ works hold the celebratory nature and affirmation that a long-awaited paradigm shift has already occurred.

“It’s real. It is a partial reflection of my existence and my experience, and that existence and experience is shared by many others,” Brooks asserts. “There’s no question that the status quo and heteronormative strictures that we’ve been living under for hundreds if not thousands of years always fight back. Change is always resisted, [therefore it’s] even more important to make the work to push against that.” Part of pushing against that resistance is to make visible what has been unseen, to take up space. Another aspect of expanding understanding and ushering in new ways of being is to increase empathetic awareness. As an artist, Brooks is interested in transmitting feelings, tapping into emotional resonances. How does he invoke this in the work? He explains:

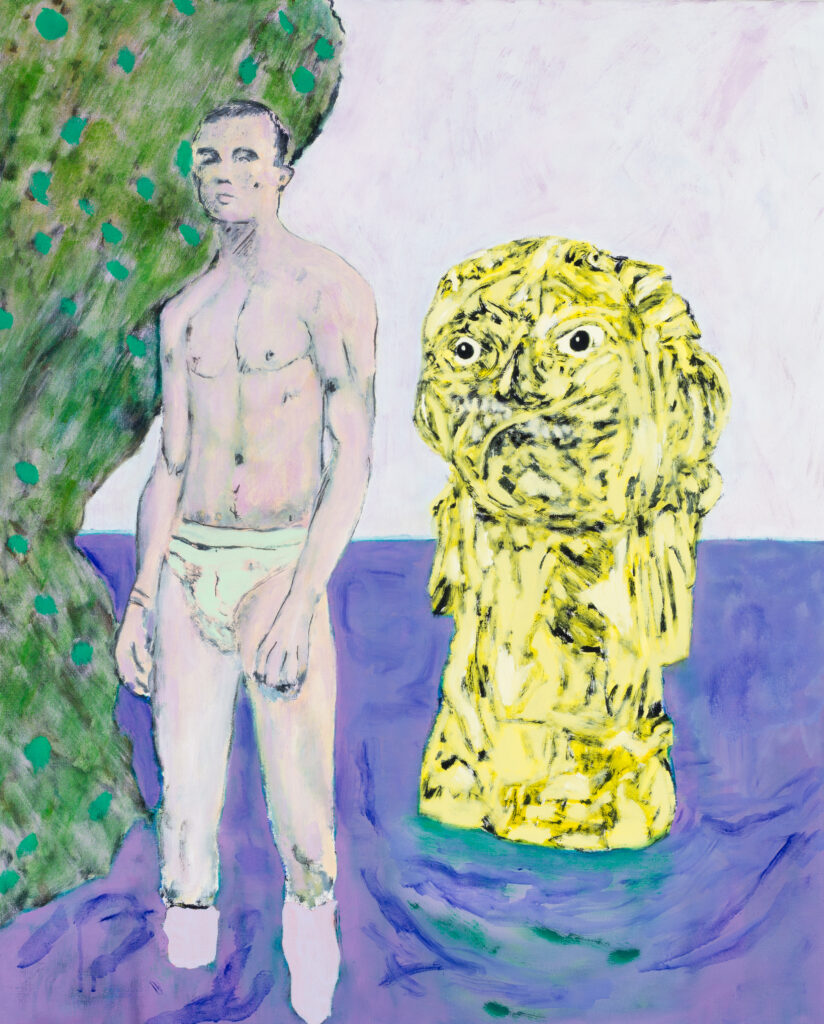

“It’s a really difficult thing to answer because it’s a really difficult thing to do. I’ve been working as an artist full time for fifteen years and in the last few years I’ve realized that that emotional realm is a strength of mine. I’m interested in developing the work along those lines. You can’t make someone feel something, there’s not an equation – it comes through subtlety. We experience the world in bodies, so there’s something about seeing a body and relating to a body that I think sets off certain sensors in a way, and then moving from there, there are positions and colors and context. In almost all of my works the faces are very still, so it’s like you’re catching someone right before something has happened or right after something has happened. Hopefully, a presence of an interior dialogue or interior life is evident, but it’s not like they’re screaming at you. I want what’s being presented to be kind of quiet – smoldering in a way.”

For Brooks, the smolder can take on different forms. Conceptually, longing and desire are two emotional resonances that have reverberated loudly throughout his oeuvre. The connection between the artist’s paintings and these two forces is one forged through Brooks’ earnest emotional life and sensitivity. Candidly, he shares:

“I think it has a lot to do with my youth. I grew up in a stable, loving home, but I was a very lonely kid. I didn’t have very many friends. I hated myself for this thing that I didn’t even understand, but I thought maybe I was, that somehow I [believed] was bad. So I spent a lot of time wanting to be someone else, or somewhere else, or something else. Weirdly, I think that’s related to this kind of longing and desire that’s sort of followed me throughout my life. I’ve spent a lot of time in Berlin, I love being there, but even when I’m there, there’s still a longing for something that’s not there, like a time that is gone…a longing for something that you don’t even understand what it is, or like another life that hasn’t existed….”

Shifting his thoughts to desire, Brooks continues.

“I am intentionally making work that has a sensuality to it, with few exceptions. There’s not necessarily much explicitness in my work, but the sort of smell – this is where we come back to the title of my [previous] show A Map of Scents – where these notions or the scent of something is probably more interesting than the thing itself, or a presentation of the thing itself. So by presenting a lot of the figures in ways that are sensual and a little provocative, it’s like dropping a scent.”

These small turns are meant to draw the viewer in but not give the entire story of the painting away. There’s a coyness tied in here, but also a sense of something deeper. Within the spaces of queer futurity theory, speculative art, and the Expressionist movement – all spaces tied to Brooks’ work – runs a current of Romanticism. An artist who deals in emotional resonances and operates from a position of longing and desire, Brooks doesn’t often consider the word romantic when thinking about his work, though he agrees it applies:

“I think it has to do with a kind of disposition – and this is a good example of the strength in using what you have and your particular makeup to do whatever it is you’re doing. Everyone is different. Some people can climb up a mountainside and stand at the top and just be so happy that they did that and think ‘I’m so strong and I’m so tough!’ And then other people – and I would put myself in this category – in that kind of a setting, I’m responding to a majesty, and that has a connection to the romantic – things that are bigger than you and older than you and existed before you and will exist after you – and I find that so fascinating and also so comforting. I love the feeling of being made to feel small and insignificant…there’s this whole other thing which is the majesty of nature and the universe and all of these billions of things that are happening that have nothing to do with you at all – don’t need you, don’t care about you, don’t respect you – that’s amazing! You can’t live in that headspace all the time, but I think if people were more willing to go there, there would be a greater commitment to being kinder to each other and to making things better. I often think about how we have a rover on Mars, but yet we’re fighting about whether or not people who love each other can have sex, or be married, or live together, or whatever – it’s crazy. So the Romantic, it’s everything else, in a way, that exists outside of the self.”

Through these thoughts, we’re given new insights with which to consider some of the points Brooks has made concerning his early life. Context shifts meaning, feelings of loneliness and separation can be redefined as one moves forward and grows. There are different ways in which people are made to feel small; some are detrimental and others are constructive. Brooks affirms:

“There are kinds of loneliness that are fundamental, and universal. But then there are other kinds that are cruel and debilitating, and I’ve experienced both. I sort of view it as part of my role as an artist to bring attention to things that fall in [the romantic] realm, because it’s so easy in contemporary daily life to get caught up in any number of things – work, and traffic, and Netflix, and whatever – and to lose a connection to the wondrousness of the universe, that you start thinking about moving your thoughts out further and further and further and things get weirder and weirder and weirder and less understandable, and we’re all in that situation. So that kind of loneliness is totally universal. And not to sound like a Utopian or something like that because I’m definitely not, but there are ways in which that kind of thinking can encourage people to be better to each other and art is one of the places where that kind of conversation is possible on a more regular basis.”

Much of contemporary life is indeed built around routine, and that kind of reawakening of the senses facilitated by the arts which Brooks refers to is important in creating space for engagement with things beyond the known, and beyond knowing. This phenomenological facet of creative culture has been tapped into by artists as a way of affecting viewers, drawing audiences into a richer connection with what they’re seeing and feeling. Brooks calls forth additional connections to his work through the practice of appropriation. Acknowledging that found imagery comes with its own weight and history, Brooks’ practice is a conversation with the audience as much as it’s a conversation with media, pop-culture, sub-culture, and other artists.

“That’s another port of entry for people, to use something that’s already in existence, because it comes with a history and it comes with connotation and comes with context – and then to shift that is fun,” Brooks says. “And it also, hopefully, allows people to understand how nothing is fixed, and to understand the complexity of things. I don’t place any different weight on where things come from. I understand they have different weight – Nick Jonas has a different cultural weight than Botticelli, for many reasons – and I don’t necessarily mean to equate them, because that’s not really what I’m interested in. It’s not about saying everything is equal or everything has the same importance, but things that are disparate and different, when combined, make something interesting. So I’m really fascinated by that process, pulling all these bizarre things together.”

Brooks has referred to the inexhaustibleness of inspiration in his practice as a result of embracing collage-based methodologies. Combining elements from art history, literature, and film with snippets of pop culture while highlighting a global queer community, Brooks takes a very holistic approach to building concept and composition within his work. Here, disparate elements of his interests coalesce into a nuanced and complex picture-world. Does the artist see these works as approaching a representation or reflection of his lived experience?

“To some degree,” Brooks concedes. “I think if you’re paying attention to what you’re doing, the work will reflect you in some way. They say every portrait is a self-portrait, and there’s perhaps some truth to that. At least, maybe, putting your emotions or ideas into something. The paintings are not diaristic. There is an element that is diaristic, but I’m not painting from life. I’m not going out with my friends and painting them at the beach, or whatever. They are imagined scenarios, and some impossible scenarios, but they do very much reflect my experience. I’m not going to put something in a painting that doesn’t mean something to me. Different things mean different things to different people…I think that’s fantastic. Because the meaning of something isn’t fixed and the context isn’t fixed, it can be more than one thing. It can be many, many things.”

Part and parcel of acknowledging the importance and slipperiness of context is an understanding of the principle of gestalt – how the whole of something adds up to more than the sum of its parts. Philosophy aside, gestalt is an incredibly effective tool in creating affect and understanding within the arts. Brooks concurs:

“I think its hugely important. Nothing exists on its own, nothing exists in a vacuum. To think that you’re making work that has no connection to anything that’s happened before is pretty senseless. It is the weight of everything together that makes things fascinating, that makes them compelling, that also makes them understandable. I have the desire and the freedom to combine whatever I want to combine in ways that I think are meaningful. I’m interested in meaning. I’m interested in transformation, and change, and affecting people. Otherwise, what’s the point, you know? If you look at the history of human existence, art has been a part of things for a very long time, so there’s something innate that compels us to record. In a way, these [artworks] are records of the fact that we were here. They should feel heavy. The more you dive into them, the more you know about them, then the heavier they should feel.”

Though you may not think of figurative paintings as overtly performative works, Brooks’ paintings are just that. His canvases are caught up with action and intention, and the notion of representing the elusive and ephemeral. His works perform the actualization of new spaces, both spaces of thought and social spaces to be inhabited with new ideas and feelings. Beyond collapsing the future and past into the present, beyond creating connections that expand common ground, beyond drawing out emotions and affecting audiences, John Brooks’ paintings perform the complex reality of existence in our hyper-connected yet untethered time. As Brooks now feels free to explore and engage a universe of possibilities through representation, combination, and speculation, so too should we the audience feel free to step into the pictorial and social spaces he is actualizing.

Top image: Artist John Brooks in his Louisville, Kentucky studio, surrounded by original work and inspirational images. Image by CM Turner.